Learning about psychiatric aspects of medical assistance in dying: a pilot survey of self-perceived educational needs among assessors in a Canadian academic hospital

Introduction

Physician-assisted death has been implemented in many jurisdictions worldwide in the past decades (1-3). In Canada, Medical assistance in dying (MAiD) was first made accessible in the province of Quebec in 2015 where the Act Respecting End-of-Life Care initially defined it as a palliative care option at the end of life (3). The rest of Canada has seen MAiD implemented in 2016 when the law Bill C-14 [An Act to Amend the Criminal Code and to Make Related Amendments to Other Acts (Medical Assistance in Dying), 2016], stated exhaustively eligibility criteria and went into force.

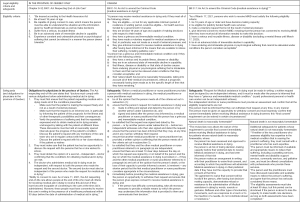

This practice has since been rapidly adopted in clinical settings, challenging medical practice in palliative care (4,5), and its accessibility remains in expansion. In the province of Quebec, for example, accessibility was extended in 2020 to people suffering from non-end-of-life illnesses, after the Superior Court of Quebec in 2019 ruled that restricting eligibility only to those persons at end of life violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (6). Considering that Court decision, the federal government then began a widespread consultation in order to revise the legislation under the name of Bill C-7 which modified again The Criminal Code and went into force in March 2021. Bill C-7 sets out two paths of accessibility: one for those patients whose natural death is reasonably foreseeable, and another for those whose death is not. It also added the possibility to waive the final consent requirement for those at-risk for losing the capacity to consent (7). See Figure 1 for legal eligibility criteria and safeguards for MAiD in Canada, as well as obligations for physicians in the province of Quebec.

Over the years, this rapid implementation of that new practice increased the need for support and education among providers (8,9). Practicing MAiD in the province of Quebec according to the law, includes making sure that the patient is well informed about therapeutic possibilities and expected prognosis, making the request freely, and experiencing persistent and unbearable suffering (3).

Literature on the psychiatric aspects of physician assisted death is rapidly evolving in Canada since MAiD is accessible. A recent prevalence study done in one Canadian center indicated that MAiD requesters often present with both physical and psychological suffering and have high rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders (such as depressive or anxiety disorders) as opposed to appropriate sadness, subthreshold psychosocial symptoms, existential distress, or fatigue often seen in context of a terminal and debilitating illness (10). Lack of capacity to consent appear also to be a frequent reason for refusal of MAiD in Canada (11), which might indicate that assessment of capacity is an important task when practicing medical assisted death. Suicidal intent and attempts have been described among those who were not deemed a candidate for MAiD, as it has been shown in a recently published case series study (12), which makes suicidal risk management an important task to master. Identifying and caring for depression has been also reported by palliative care physicians as a complex and challenging task, as well as a desired topic to be trained on (13). Depression is in fact a frequent psychiatric comorbidity among terminally ill, as well as in medically ill who also express wishes for hastened death (14-16).

These psychiatric topics are relevant and therefore represent important competencies for physicians practicing MAiD. Little is known about how often psychiatry consultants are involved in MAiD cases in that jurisdiction, although previous data indicated psychiatrists are rarely involved in physician-assisted death around the world (17). This fact might suggest that providers and assessors manage themselves the psychiatric issues. More recently, Isenberg-Grzeda et al. revealed in a Canadian prevalence study among requesters (n=155) that psychiatrists were involved mostly in cases where psychiatric comorbidity is present (41.7%, n=60), especially for patients with severe mental illness where psychiatrists were involvement reaches 80% of cases (10).

To our knowledge, very few training programs designed for assessors specifically addressing these psychiatric issues have been described (1,18,19), and recent data published in 2021 indicates that providers still expressed the desire for more guidance and training (20). Bator et al. [2017] for example had reported that Canadian medical students’ need for training on communication skills, medicolegal and religious aspects of MAiD are frequent and mostly unmet (21). Another study from Australia has described a model for training new assessors in their jurisdiction where assisted death has been recently made accessible (22). A framework to enhance training in end-of-life care and MAiD practice in Canada has also been published, although more data is needed to know if it is feasible, efficacious, and generalizable (19). Data on the level of interest for further training and preferred format on these specific competencies of MAiD practice among requesters in Canada is still lacking and would be especially important to have as MAiD accessibility is expected to be expanded in 2023, as per Bill C-7, to patients with only mental illness as a medical condition.

To make training programs effective in changing doctors’ clinical practice, identifying the learners’ needs is crucial in medical education (23,24). Educational needs of MAiD assessors have been explored, but to our knowledge, no study have specifically focused on psychiatric aspects. By conducting a cross-sectional online survey, our pilot study was designed to explore self-perceived educational needs among MAiD assessors in one academic center. Although MAiD often occur in an interprofessional context as nurses, pharmacist, social workers, psychologists might be involved in the care of the requester, the focus of our study was on assessors which are responsible to fulfill the legal criteria checklist before MAiD can be provided. In the province of Quebec, only physicians can be MAiD assessors or providers, while in the rest of Canada, both physicians and nurse practitioners can provide MAiD. We present the following article in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-422/rc).

Methods

The pilot study took place at a 750-bed academic and tertiary care hospital center in the province of Quebec (Canada). The survey was performed in 2017, one year and a half after the government of Quebec enacted its law on MAiD for end-of-life patients. At that time, assessor was invited by Quebec’s Collège des Médecins to participate in a training program, which addressed mainly protocols and legal issues, and was not designed to focus specifically on psychosocial and psychiatric issues. None of the recent law modifications had occurred at the time of the study. MAiD was in fact provided solely at the end of life as per the eligibility criteria and was considered a new medical practice in palliative context. Since then, as mentioned, in the province of Quebec, MAiD has been made accessible to all patients with progressive and irreversible decline, not only for those suffering from an end-of-life condition. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The research design was approved by the scientific and research ethics committee of Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (approval No. 16.384). A cross-sectional self-administered web-based anonymous survey was conducted, like those used in medical education to explore learning expectations (25,26). Informed consent was taken from all the participants. Most questions were close-ended and used a Likert scale to measure participants’ estimated level of knowledge on psychiatric aspects involved in MAiD requests. Very few were open-ended with text box responses. The questionnaire was developed by our research group to capture the MAiD assessors’ views of their educational needs (see Appendix 1). It took approximately 5 to 10 minutes to complete it. Specifically, questions were designed to establish participant profile and explore their perceptions regarding the educational needs on psychiatric aspects involved in assessing a MAiD request. To reach optimal validity and reliability, we used several strategies recognized as best practices in survey-based research (27,28). In fact, to ensure the clarity and the relevance of the questionnaire, a pre-test was done with a research member included in the target population, and response time was measured (26,29).

The main inclusion criteria were practicing medicine at our center and having performed at least one eligibility assessment for MAiD. Physicians-in-training and those working in other hospitals were excluded. A non-probability sampling was used. All 25 physicians involved in MAiD request assessments were first contacted by the chief physician via email to know if they agreed to be solicited for the study. All agreed to be invited. An email was then sent to them with the consent form and a link to the online questionnaire which recorded the answers anonymously. Participants had 3 weeks to sign the consent form and complete the survey. There was no incentive used to motivate participation. A reminder email was sent one week before the end of this three-week period.

Statistical and descriptive analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analysis was done with the collected data. Response rate was calculated as the percentage of the population sample that responded to the survey. A chi-square test was also done to compare groups of responders on different between categorical variables (i.e., previous training on palliative care or MAiD, years of experience, medical specialty and level of self-perceived competencies).

Results

The response rate obtained in that pilot study was 76%. Of the 25 physicians approached by our research team, 19 participants fully answered anonymously our online survey (n=19). Six did not signed the consent nor completed the poll. We do not know the reasons of declining the participation. Responders were about twice as many men as women [13 men (68%) vs. 6 women (32%)]. Most of them (58%) had over 20 years’ experience and were from different medical specialties (such as family medicine, oncology, surgery, anesthesiology, etc.) (see Table 1), which were representatives of the underlying population selected. Section 1 addresses responders’ demographics and background (see Table 1); the non-responders were not contacted to gather such information on their profile. While 9 participants (47%) had no training in palliative care, 37% mentioned not having been trained in MAiD assessments tasks whatsoever. Less than half our participants had provided palliative care in their practice (42%). Fifteen of them (79%) had provided MAiD at least once.

Table 1

| Demographics and background | Survey items | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 13 | 68.4 |

| Female | 6 | 31.6 | |

| Years of medical practice | 0–5 years | 3 | 15.8 |

| 6–10 years | 2 | 10.5 | |

| 11–15 years | 1 | 5.3 | |

| 16–20 years | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Over 20 years | 11 | 57.9 | |

| Medical specialty | General practice | 3 | 15.8 |

| Medical oncology | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Urology | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Anesthesiology | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Hemato-oncology | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Palliative care | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Gastroenterology | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Radio-oncology | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Endocrinology | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Pneumology | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Cardiology | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Addictions medicine | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Previous training in palliative care* | Previous training | ||

| Internship rotations (residency) | 6 | 31.5 | |

| Personal reading | 6 | 31.5 | |

| Medical conferences | 4 | 21.1 | |

| Fellowship training | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Clerkship rotations (med. school) | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Training for family physicians | 1 | 5.2 | |

| Online training | 1 | 5.2 | |

| No training | 9 | 47.4 | |

| Previous training in Medical Assistance in Dying* | Personal reading | 7 | 36.8 |

| Medical conferences | 6 | 31.6 | |

| Hospital-based online training | 5 | 26.3 | |

| Other online training | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Training day from the Collège des Médecins du Québec | 1 | 5.2 | |

| No training | 7 | 36.8 | |

| Ever took care of an end-of-life patient | Yes | 18 | 94.7 |

| No | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Ever worked in palliative care | Yes | 8 | 42.1 |

| No | 11 | 57.9 | |

| Ever performed medical assistance in dying | Yes | 15 | 78.9 |

| No | 4 | 21.1 |

*, more than one answer was accepted for that question.

Section 2 addressed perceived learning needs by estimated levels of competency in selected areas of psychiatric aspects of MAiD (see Table 2). Participants reported their highest level of knowledge in different areas, such as evaluating capacity to consent to MAiD, distinguishing a MAiD request from suicidal ideation, and evaluating psychological suffering. Identifying needs and disorders, as well as determination of capacity of patients were domains where physicians reported higher levels of competency. The domains in which they reported having the lowest level of competency were treating psychiatric disorders, including depression, with pharmacotherapy and with psychotherapy (53% reported a poor level).

Table 2

| Competency | Estimated levels of competency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very poor | Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | |

| Identifying needs/identifying and treating psychiatric disorders | |||||

| Evaluating suffering* | – | 5 | 26 | 53 | 16 |

| Identifying patients’ psychosocial needs | – | 11 | 37 | 47 | 5 |

| Identifying psychiatric disorders | – | 5 | 42 | 47 | 5 |

| Identifying/treating end-of-life delirium | – | 21 | 42 | 26 | 11 |

| Identifying/treating end-of-life depression | 5 | 32 | 53 | 11 | - |

| Distinguishing Medical assistance in dying requests from suicidal ideation | – | – | 21 | 74 | 5 |

| Meeting psychosocial needs/offering psychiatric treatments | |||||

| Meeting psychosocial needs | 5 | 16 | 42 | 32 | 5 |

| Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorder | 11 | 53 | 32 | 5 | – |

| Psychotherapy for psychiatric disorders | 5 | 53 | 37 | 5 | – |

| Determination of capacity | |||||

| Evaluating capacity to consent to MAiD | – | – | 21 | 58 | 21 |

*, definition of suffering was given in the question in reference to the criterion of Law 2: “Must experience constant and unbearable physical or psychological suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner the person deems tolerable”.

Section 3 was on teaching content preferences (see Table 3). The interest level in further training was the highest for end-of-life psychiatric disorders and evaluating capacity to consent to MAiD. End-of-life spiritual and religious issues were the only aspect in which some reported no interest at all (16%). However, all areas had a minimum of 79% participants being at least somewhat interested in further training.

Table 3

| Topics | Interest level for further training (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all interested | Slightly interested | Somewhat interested | Very interested | Extremely interested | |

| Exploring and evaluating suffering | – | 16 | 32 | 32 | 21 |

| Evaluating capacity to consent | – | – | 32 | 58 | 11 |

| End-of-life psychosocial issues | – | 16 | 42 | 26 | 16 |

| End-of life psychiatric symptoms and disorders | – | 11 | 16 | 63 | 11 |

| End-of-life spiritual and religious issues | 16 | 5 | 37 | 37 | 5 |

| End-of-life existential issues | – | 16 | 26 | 37 | 21 |

| Differences between a Medical assistance in dying request and suicidal ideation | – | 11 | 32 | 47 | 11 |

| Natural caregivers’ and families’ reactions | – | 5 | 37 | 42 | 16 |

| Healthcare professionals’ reactions | – | 16 | 32 | 32 | 21 |

Section 4 scoped teaching format preferences, including e-learning (30,31) (see Table 4). Among the potential formats proposed, 63% of respondents chose group-based learning (e.g., workshops), while 53% of participants chose e-learning. It is worthwhile noting that for some questions participants could choose more than one answer.

Table 4

| Format preferences | Survey items | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred learning formats* | Group-based learning (e.g., workshops) | 12 | 63.2 |

| E-learning | 10 | 52.6 | |

| Lectures | 6 | 31.6 | |

| Preferred time to participate in such training* | Outside of work hours | 13 | 68.4 |

| During work hours | 11 | 57.9 | |

| Would accept to pay | Yes | 10 | 52.6 |

| No | 9 | 47.4 | |

| Would be interested in e-learning | Yes | 11 | 57.9 |

| No | 5 | 26.3 | |

| No opinion | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Ideal electronic modality for receiving e-learning* | Personal computer | 13 | 68.4 |

| Work computer | 7 | 36.8 | |

| Smart phone | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Tablet | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Ideal time for one e-learning module | 5 min | 1 | 5.3 |

| 10 min | 8 | 42.1 | |

| 15 min | 6 | 31.6 | |

| More than 15 min | 1 | 5.3 | |

| No opinion | 3 | 15.7 | |

| Ideal total time for e-learning | 20 min | 3 | 15.8 |

| 30 min | 6 | 31.6 | |

| 40 min | 4 | 21.1 | |

| More than 40 min | 3 | 15.8 | |

| No opinion | 3 | 15.7 |

*, more than one answer was accepted for this question.

From statistical analysis, we found no statistically significant difference between categorical variables, such as assessors’ medical specialty, previous training, years of experience and self-perceived level of competence, with a chi-carre test.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this pilot study was the first to explore educational needs on psychiatric aspects among MAiD assessors in the province of Quebec. Despite a tendency of response rate to decline in clinician surveys in the past decades, 76% of our sample completed the online survey, which would be consider as a high response rate for clinicians as it is above 60% (32,33). Based on our findings, 79% of the respondents have performed MAiD before completing the survey, which might indicate that MAiD had become part their medical practice to relieve suffering at the end-of-life. However, our results also indicate that most participants had not received formal education on psychiatric aspects of MAiD before practicing it and showed a strong interest to be better trained in those topics. This finding is consistent with recent data indicating that significant informational needs have been found among health care professionals, and members of the public as well, on the relational, emotional and symbolic aspects, which go beyond medical and legal aspects of this practice (34).

Furthermore, even though 95% of participants had reported taking care of patients at the end of life on a regular basis, 47% had never received any formal palliative care or end-of-life training, which usually includes psychosocial issues and psychiatric symptoms management. This finding is surprising since all assessors must in every case require such competencies in evaluating if the individual who requests MAiD is able to “understand the situation and the information given by health professionals as well as make decisions”, and “experience constant and unbearable physical or psychological suffering” (3). In fact, despite a high prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and disorders in palliative care, there is still very little post-graduate training on these conditions, which are often underrecognized and undertreated in end-of-life contexts (35,36).

In our pilot study, the participants assessed their own levels of competency with regards to psychiatric aspects of MAiD as high. For example, an important proportion of participants reported confidence in distinguishing a MAiD request from suicidal ideation, which appears consistent with the findings of a recent study that documented among requesters, assessors and citizens that MAiD might be perceived differently compared to suicide (37). Surprisingly, despite this high-level of confidence, this topic appeared to interest almost half of the responders (very and extremely interested: 58%) as a topic that should be addressed in additional training, which makes us wonder if overconfidence might have been here a significant factor in those results, or a bind where physicians must regard themselves as capable of assessing suicidality for legal purpose. Differentiating suicidal ideation as a depressive symptom from a desire to hasten death with a MAiD request, can be in some cases a learning opportunity for which providers might ask for an independent opinion of a psychiatrist. Consultation-liaison psychiatrits have been in fact involved in complexes cases of physician-assisted death around the world and might offer assistance in clarifying capacity, identifying mental disorders or helping along with the rest of the team to resolve complex relational issues or manage suicidality (17,38,39).

The responders reported the lowest level of competency were treating psychiatrists disorders, including depression, with pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy. This might not be surprising as clinicians might feel that they do not currently have strong data on the efficacy nonpharmacological or pharmacological interventions for depressed patients at end of life, especially for those with extremely short prognoses (13).

Furthermore, nearly 80% of participants reported they had a high level of competency in assessing capacity to consent to MAiD. This finding might suggest overconfidence among our participants as previous data indicated physicians might have difficulties to detect lack of capacity in palliative care settings. In fact, one study revealed a high rate of poor decision-making abilities among the terminally ill (40). Another one showed significant cognitive impairments in hospice care patients, despite an absence of documented or clinically obvious impairment, which had the authors recommending assessment of cognition in hospice patients, as it may interfere with decision-making capacity (41). Determining capacity to consent to MAiD is an important and complex task since a significant proportion of patients might encounter different clinical situations that undermine or impair decisional capacity in advanced diseased (42). Some researchers have even studied the use of tools in predicting which patient might lose it before the provision of MAiD (11).

In the presence of psychiatric comorbidity, the decision-making capacity to consent is rarely affected, but can be in some severe cases (43). Best practices of capacity to consent to treatment include considering variations in capacity over time and depending on the type of decision, the severity of symptoms, and the phase of the mental illness (44). Consequently, although every assessor has to feel competent to assess capacity, any overestimation of that competence could potentially and to some extent result in lack of recognition of individuals without capacity or missed opportunity to ask for a specialized advice, such as to a consultation-liaison psychiatrist when complexity arise from cases (45). In that sense, it appears important to acknowledge that decision making might be a complex task best done within peer environments.

Nearly 70% of participants reported their competency level as “good” or “very good” regarding the evaluation of suffering among requesters. It is unclear whether these participants meant they were comfortable trying to explore suffering, or whether they were able to simply confirm its existence as subjectively reported by the patient accordingly to the Canadian legal requirements. Evaluating suffering can be a complex task for experienced clinicians, as it requires a high degree of skills and sufficient time (46). In fact, suffering is by definition global, non-quantifiable, multidimensional, and influenced by many factors, including an existential dimension (47-50). The challenges facing the terminally ill can be physical, psychological, existential, and spiritual (51).

Finally, while e-learning is increasing in popularity in medical training (30,52), our participants preferred group-based learning, which was unexpected. Although the questionnaire did not specifically ask to the participants why they had that preference, many reasons could explain it. We wonder if it may be due to the complex nature of psychiatric aspects of MAiD, which participants might find to be better explained, explored and discussed through in-person group teaching. Another possibility could be that most of our participants having over 20 years of experience might be less comfortable with web-based e-learning. Of note, we wonder if the same study was performed in post-COVID era, we would have obtained the same results as virtual, and more recently hybrid formats, have expanded rapidly in CME activities due to the pandemic (53). On the other hand, learning and reflecting on the depth of psychological or ethical issues with intersubjective shared experience might be better pursued in face-to-face format.

Despite its strengths, including high response rate, exploring perspective of new MAiD practitioners, this pilot study has also limitations. First, it is worth mentioning while the response rate reached 76%, the sample size remains small. As it was performed in only one center and in the province of Quebec where the legal criteria to be eligible to MAiD are somewhat different from the rest of Canada, its generalizability is also limited. The fact that 79% of our responders had previously provided MAiD might indicate a tendency of responders to report positive views towards physician-assisted death to relieve unbearable suffering, as opposed to physicians without experience or hesitant to medical assistance in dying. Moreover, the extent to which our participants perceived their real learning needs adequately is unknown since it was not objectively measured. In fact, some physicians have a limited ability to self-assess their own competencies (54). Therefore, a future multicenter study with a larger participant population with higher variation would help validating our pilot study.

Conclusions

MAiD is an evolving practice and an important area of medicine that warrants formal training for physicians where jurisdictions make it accessible. Patients at the end of life who request for assisted death are at risk for psychiatric comorbidities as well as psychosocial issues. Despite some limitations, our pilot study revealed that physicians reported a high level of competency in terms of psychiatric aspects among MAiD requesters, but that they also expressed a strong desire for additional education. Future research should clarify if this high level of self-competency constitutes an overestimation of their actual knowledge, especially in the context where MAiD is now practiced. Objective measurement of competences would be at this point interesting since there is a lack of training not only on psychiatric aspects of MAiD, but also on other aspects of palliative care. Exploring such educational needs on that topic among in diverse healthcare professionals and in different clinical settings (including in other Canadian provinces) would also be relevant. How psychiatrists could contribute to this educational challenge is another avenue of research. Providing high-quality training programs to meet patients’ needs continues to be a priority as access to MAiD has been progressively expanded in Canada.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Caroline Ouellet for her help in validating the questionnaire, Marie Hermans from the Académie CHUM for her technical support in developing the online questionnaire, and the Director of Professional Services of the CHUM for the help in recruiting participants.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-422/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-422/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-422/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-422/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the scientific and research ethics committee of the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (approval No. 16.384) and informed consent was taken from all the participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Li M, Rodin G. Medical Assistance in Dying. N Engl J Med 2017;377:897-8. [PubMed]

- Downie J, Gupta M, Cavalli S, et al. Assistance in dying: A comparative look at legal definitions. Death Stud 2022;46:1547-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Act respecting end-of-life care (S-32.0001). (Accessed online on June 12th, 2021). Available online: https://www.quebec.ca/en/health/health-system-and-services/end-of-life-care/medical-aid-in-dying/requirements

- Ho A, Norman JS, Joolaee S, et al. How does Medical Assistance in Dying affect end-of-life care planning discussions? Experiences of Canadian multidisciplinary palliative care providers. Palliat Care Soc Pract 2021;15:26323524211045996. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joolaee S, Ho A, Serota K, et al. Medical assistance in dying legislation: Hospice palliative care providers' perspectives. Nurs Ethics 2022;29:231-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pesut B, Thorne S, Wright DK, et al. Navigating medical assistance in dying from Bill C-14 to Bill C-7: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:1195. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bill C-7 and Bill C-14. An Act to amend the Criminal Code (medical assistance in dying). (Accessed on June 12th, 2021). Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/ad-am/bk-di.html; https://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/bill/C-14/royal-assent

- Oczkowski SJW, Crawshaw D, Austin P, et al. How We Can Improve the Quality of Care for Patients Requesting Medical Assistance in Dying: A Qualitative Study of Health Care Providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021;61:513-521.e8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiebe E, Green S, Wiebe K. Medical assistance in dying (MAiD) in Canada: practical aspects for healthcare teams. Ann Palliat Med 2021;10:3586-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isenberg-Grzeda E, Nolen A, Selby D, et al. High rates of psychiatric comorbidity among requesters of medical assistance in dying: Results of a Canadian prevalence study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2021;69:7-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Selby D, Meaney C, Bean S, et al. Factors predicting the risk of loss of decisional capacity for medical assistance in dying: a retrospective database review. CMAJ Open 2020;8:E825-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isenberg-Grzeda E, Bean S, Cohen C, et al. Suicide Attempt After Determination of Ineligibility for Assisted Death: A Case Series. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:158-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee W, Chang S, DiGiacomo M, et al. Caring for depression in the dying is complex and challenging - survey of palliative physicians. BMC Palliat Care 2022;21:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Depression, Hopelessness, and suicidal ideation in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics 1998;39:366-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, Skirko MG, et al. Depression and anxiety disorders in palliative cancer care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:118-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crespo I, Rodríguez-Prat A, Monforte-Royo C, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with advanced cancer who express a wish to hasten death: A comparative study. Palliat Med 2020;34:630-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCormack R, Fléchais R. The role of psychiatrists and mental disorder in assisted dying practices around the world: a review of the legislation and official reports. Psychosomatics 2012;53:319-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li M, Watt S, Escaf M, et al. Medical Assistance in Dying - Implementing a Hospital-Based Program in Canada. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2082-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gewarges M, Gencher J, Rodin G, et al. Medical Assistance in Dying: A Point of Care Educational Framework For Attending Physicians. Teach Learn Med 2020;32:231-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Winters JP, Pickering N, Jaye C. Because it was new: Unexpected experiences of physician providers during Canada's early years of legal medical assistance in dying. Health Policy 2021;125:1489-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bator EX, Philpott B, Costa AP. This moral coil: a cross-sectional survey of Canadian medical student attitudes toward medical assistance in dying. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18:58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- White BP, Willmott L, Close E, et al. Development of Voluntary Assisted Dying Training in Victoria, Australia: A Model for Consideration. J Palliat Care 2021;36:162-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norman GR, Shannon SI, Marrin ML. The need for needs assessment in continuing medical education. BMJ 2004;328:999-1001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holm HA. Quality issues in continuing medical education. BMJ 1998;316:621-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Magee C, Rickards G, A, Byars L, et al. Tracing the steps of survey design: a graduate medical education research example. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5:1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colbert CY, French JC, Arroliga AC, et al. Best practice versus actual practice: an audit of survey pretesting practices reported in a sample of medical education journals. Med Educ Online 2019;24:1673596. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Artino AR Jr, Phillips AW, Utrankar A, et al. "The Questions Shape the Answers": Assessing the Quality of Published Survey Instruments in Health Professions Education Research. Acad Med 2018;93:456-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Artino AR Jr, Durning SJ, Sklar DP. Guidelines for Reporting Survey-Based Research Submitted to Academic Medicine. Acad Med 2018;93:337-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rickards G, Magee C, Artino AR Jr. You Can't Fix by Analysis What You've Spoiled by Design: Developing Survey Instruments and Collecting Validity Evidence. J Grad Med Educ 2012;4:407-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, et al. Internet-based learning in the health professions: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2008;300:1181-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. The impact of E-learning in medical education. Acad Med 2006;81:207-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiebe ER, Kaczorowski J, MacKay J. Why are response rates in clinician surveys declining? Can Fam Physician 2012;58:e225-8. [PubMed]

- Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ 2008;179:245-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boivin A, Gauvin FP, Garnon G, et al. Information needs of francophone health care professionals and the public with regard to medical assistance in dying in Quebec: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open 2019;7:E190-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin SA, Ferris FD. The opportunity for psychiatry in palliative care. Can J Psychiatry 2008;53:713-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin SA, Montross LP, Bhat RG, et al. Psychiatry resident education in palliative care: opportunities, desired training, and outcomes of a targeted educational intervention. Psychosomatics 2011;52:530-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiebe ER, Shaw J, Kelly M, et al. Suicide vs medical assistance in dying (MAiD): A secondary qualitative analysis. Death Stud 2020;44:802-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois JA, Mariano MT, Wilkins JM, et al. Physician-Assisted Death Psychiatric Assessment: A Standardized Protocol to Conform to the California End of Life Option Act. Psychosomatics 2018;59:441-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stewart DE, Rodin G, Li M. Consultation-liaison psychiatry and physician-assisted death. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018;55:15-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sorger BM, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Decision-making capacity in elderly, terminally ill patients with cancer. Behav Sci Law 2007;25:393-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burton CZ, Twamley EW, Lee LC, et al. Undetected cognitive impairment and decision-making capacity in patients receiving hospice care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;20:306-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McFarland DC, Blackler L, Hlubocky FJ, et al. Decisional Capacity Determination In Patients With Cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2020;34:203-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calcedo-Barba A, Fructuoso A, Martinez-Raga J, et al. A meta-review of literature reviews assessing the capacity of patients with severe mental disorders to make decisions about their healthcare. BMC Psychiatry 2020;20:339. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pons EV, Salvador-Carulla L, Calcedo-Barba A, et al. The capacity of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder individuals to make autonomous decisions about pharmacological treatments for their illness in real life: A scoping review. Health Sci Rep 2020;3:e179. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strouse TB. Requests for PAD and the Assessment of Capacity. Hastings Cent Rep 2019;49:4-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pesut B, Wright DK, Thorne S, et al. What's suffering got to do with it? A qualitative study of suffering in the context of Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID). BMC Palliat Care 2021;20:174. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kissane DW. The relief of existential suffering. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1501-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cassell EJ. Recognizing suffering. Hastings Cent Rep 1991;21:24-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. BMJ 2007;335:184-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, McPherson CJ, et al. Suffering with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1691-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, et al. The landscape of distress in the terminally ill. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:641-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pelayo-Alvarez M, Perez-Hoyos S, Agra-Varela Y. Clinical effectiveness of online training in palliative care of primary care physicians. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1188-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Price DW, Campbell CM. Rapid Retooling, Acquiring New Skills, and Competencies in the Pandemic Era: Implications and Expectations for Physician Continuing Professional Development. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2020;40:74-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, et al. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1094-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]