Competencies for quality spiritual care in palliative care in Latin America: from the Spirituality Commission of the Latin American Association for Palliative Care

Introduction

The spiritual dimension of palliative care was recognized by Dame Cicely Saunders in the definition of “total pain” (1,2), and the World Health Organization established that relieving pain and spiritual suffering is an ethical responsibility of health systems and healthcare professionals (3). According to the bioethics of health care, caring for another person consists of responding to the individual’s physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs with responsibility and competence (4,5). Also, over the past decade, the scientific literature reports have emphasized that spiritual care is an essential component of palliative care, highlighting the need for quality spiritual care training for all healthcare professionals (6-10).

To facilitate the adoption of a common language for spiritual care, the following definition of spirituality proposed by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (9) was used: “spirituality is defined as the dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity that relates the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose, and the way they experience their connection with the moment, with themselves, with others, with nature, and with the significant or sacred”. This is the most widely used definition in the international literature on spiritual care in palliative care. Moreover, spirituality is used as a broad term that encompasses the transcendental, religious, and existential needs of patients and caregivers.

According to the World Health Organization, evidence-based care practices are necessary for quality palliative care, a principle upon which quality spiritual care must be based (3). Furthermore, according to international best practices, quality spiritual care is based on a holistic biopsychosocial and spiritual model (7,10-15) that is centered on the person (8-11,15). Ideally, this care is provided by an interdisciplinary palliative care team (hereafter referred to as a team) (7-10,13-19). Whereas general spiritual care is the responsibility of all team members, ideally, each team will have a professional spiritual care provider who is responsible for specialized spiritual care (7,9,10,13-15,17,20,21). Spiritual care generalists must have basic training in spiritual care to be able to identify any spiritual crisis/need, to complete a spiritual history and do basic spiritual care interventions (such as compassionate presence, listening and/or refer to a Spiritual care specialist). It is important for the team members to know themselves and be able to recognize when a spiritual care specialist is needed. Whenever spiritual care generalists find spiritual distress related to conflicted belief systems, or beliefs systems that affect the decision making process, loss of faith, concerns about meaning and purpose of life, conflicts with God or the church dogma, or feeling guilt and fear, abandonment, and anger at God, or concerns about hopes, values, or need of religious services, a spiritual care specialist/professional needs to be called.

A spiritual care specialist (in many countries referred as Chaplain) is a person that has received specialized training and carries out a deeper assessment of spiritual needs and resources and creates a plan of care that includes spiritual interventions. The word Chaplain in Spanish means “Capellan”, a term used to describe mainly a priest serving his faith community outside the walls of a church (prison, hospital, convent). Therefore, for the Latin American context, in this document we used the term Spiritual Care specialist or Spiritual Care Professional instead of the word chaplain.

The spiritual care specialist/professional is a member of the team with the same duties and rights as other team members which includes assuring his/her professional suitability, access to medical records, adequate compensation, and continuing education opportunities (9). This team member is responsible of overseeing the harmonizing of general spiritual care and the structuring, implementation, and documentation of a specialized spiritual care plan for more complicated cases. When including a spiritual care professional or provider on the team is not possible, a member of the team who is trained to provide general spiritual care can meet this need temporarily and take over the coordination of spiritual care (7,13,15). The person responsible for spiritual care must establish alliances and collaborative relationships with organizations and/or other specialists (7,9,10,13,14).

Spiritual care is best achieved by discovering the ethical characteristics and beliefs of the patient. Team members must be prepared to respond to patients’ diverse spiritual and religious needs, the potential differences may be significant when we consider that the spiritual needs of a person who is agnostic or atheist will differ from those of one who identifies as religious or believes in a higher being. Even individuals within the Christian tradition have great diversity of beliefs and practices that may have a direct impact on the clinical context and medical decision making.

Spiritual care is a fundamental part of palliative care. However, in Latin America, it has yet to impact quality care to the same degree as other aspects of the general care. Rigorous research initiatives are needed to determine how different aspects of spirituality, including its different cultural, social, and religious expressions, impact quality of life, symptom expression, coping mechanisms, and clinical treatments (22,23). In addition, we must recognize that most of the research in spirituality and spiritual care is performed in North America and Europe, which leaves a great knowledge gap concerning spiritual care in the cultural and social context of Latin America. The ability to design and implement spiritual care research projects in one’s own cultural context is an important part of clinicians’ professional development (24-26).

Defining the competencies that each member of the team must have to provide quality spiritual care is fundamental. All members of the team should receive training and continuing evidenced-based education in spiritual care relevant to their roles on the team (7,9,16,17,19,27-29).

Clinical spiritual care in palliative care: Latin American context

Currently, 1,562 palliative care teams are working in 17 countries in Latin America (30). According to the Latin American Association for Palliative Care (ALCP), this number represents a significant increase in palliative care services delivered in Latin America, although the implementation of palliative care in this region remains insufficient in view of the needs of patients living with advanced or terminal illnesses. Also, documentation of the ability of teams to respond to patients’ religious and spiritual needs in Latin America is lacking. This is especially important considering that in Latin America, 97% and 89% of individuals living with advanced cancer identify themselves as having spiritual beliefs and religious beliefs, respectively, and that these beliefs have significant impact on their lives. At the same time, patients living with advanced illnesses have a high prevalence of spiritual distress (52–67%), which causes worsening of emotional distress, coping strategies, and quality of life (24,31). Among these vulnerable populations, 60% reported that their spiritual/religious needs had not been supported by their clinical teams (24). Latin America is rich in religious and spiritual diversity, and this must be considered when providing quality spiritual care to patients living with advanced or terminal illnesses, and those approaching death, as well as to their caregivers. Supporting and strengthening all educational training initiatives and activities for teams to enable them to provide high-quality spiritual care to different communities in Latin America are extremely important.

According to a report titled Religion in Latin America: Widespread Change in a Historically Catholic Region by the Pew Research Center in 2014 (32), noteworthy changes in religious affiliation, beliefs, and practices have occurred in this region. Specifically, from 1900 to the 1960s, at least 90% of the population of Latin America was Roman Catholic. Currently, only 69% of adults in the entire region identify as Catholic, 19% identify as Protestant, and 8% have no religious affiliation (this category includes people who identify as atheist, as agnostic, or with no religion in particular). In addition, the report showed that many people who identify as Christian have adopted the beliefs and practices of Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Brazilian, or indigenous religions. This increased diversity of spiritual and religious beliefs has clear implications for palliative care. For example, a useful fact for teams to know is that according to this report, 59.3% of Protestants and 29.7% of Catholics reported having witnessed a divine healing. In addition, 53.6% of Protestants and 27.4% of Catholics reported that religion was very important in their lives and that they participated in daily prayers and weekly religious services. To this diverse landscape we must add the needs of other Christian communities such as Seventh-Day Adventists, Mormons, and Jehovah’s Witnesses, who have beliefs and practices that differ from those in traditional Protestantism (32).

Another important part of Latin America’s religious diversity is its indigenous native spiritual and religious practices. Latin America has more than 800 indigenous groups (some in voluntary isolation and others in large urban settings) with a total population of close to 45 million people characterized by wide demographic, social, territorial, and political diversity (33). Other important spiritual/religious traditions that may impact health care and end-of-life care include African traditions (e.g., Umbanda, Santeria, Candomblé), Judaism, Baha’i, and Islam (34-37). Providing quality spiritual care for patients in these communities can be a major challenge for traditional healthcare systems because of the diversity of cultures, languages, and spiritual and religious beliefs and practices together with a lack of training in spiritual care and communication skills (38-40).

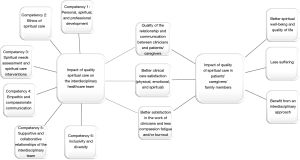

There is an important diversity in cultural, spiritual and religious aspects among teams in Latin America, as well as in their many clinical practices. Spiritual care has been provided by palliative care teams through different experiences in Latin American countries. Thus, having spiritual care competencies defined as “integrated pieces of knowledge, skills and attitudes that can be used to carry out a professional task successfully” (19) can improve the practices of care teams, alleviate the spiritual suffering of people living with debilitating advanced or terminal chronic illnesses and of their caregivers, improve the relationships of patients and/or caregivers with clinicians and improve job satisfaction and decrease burnout among team members (Figure 1). Herein the purpose of this paper is to provide to Palliative Care Teams the competencies required for High quality spiritual care in the Latin America setting, with relevant observable behaviors related to each competency and clinical implications of care that are applicable to members of the team.

Methods

Development of competencies in spiritual care for palliative care teams in Latin America

As a first step in the development of the Competencies in Spiritual Care in Latin America, in 2018, members of different disciplines founded the Spirituality Commission of the ALCP (one spiritual care specialist, seven palliative care physicians, one palliative care nurse, two psychologists, one hospice care leader and one volunteer and care coordinator for pediatric palliative care). One of the main objectives of this commission was to introduce and promote quality spiritual care (assessment, interventions, and follow-up) as part of the comprehensive care provided to patients in the palliative care setting and their caregivers (41). Through continuing education and the inclusion of people with expertise in spiritual care, based on focus group process the Spirituality Commission created important guidelines for incorporating spiritual care in palliative care and improving the quality of spiritual care provided by teams in Latin American countries. To improve the quality of spiritual care, promote opportunities for spiritual formation that align with the international recommendations and experiences and facilitate the development of research projects that reflect the perspectives and needs of the Latin American population, a common vocabulary for spiritual care in clinical practice (Table 1) and quality standards for general quality spiritual care for team members (Table 2) were provided by our group (10,18).

Table 1

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Clinical spiritual care | • Interventions with the patient, family, or caregivers to assist in the search for meaning and purpose through connections with the self, others, and the significant or sacred. Specialized spiritual care refers to the treatment of spiritual crisis or complex spiritual needs (7,11) and is provided by a spiritual care professional or spiritual advisor (9). Generalist spiritual care is provided by any member of the interdisciplinary team (9) |

| Clinical spiritual counselor | • Member of the interdisciplinary team who is dedicated exclusively to spiritual care (in Spanish, “Consejero Espiritual Clínico”, to establish a difference with the term chaplain, which in our context, refers to a priest serving his faith community outside the walls of a church (prison, hospital, convent) |

| Crisis/anguish/spiritual pain | • State of suffering related to the limited ability to experience the meaning of life through connections with oneself, others, the world, or a higher being (9) |

| Cultural competence | • Capacity of health professionals and institutions to (I) value diversity, (II) evaluate and recognize their own cultural context, (III) manage the dynamics caused by differences, (IV) acquire and institutionalize knowledge of cultural diversity, and (V) adapt to the diversity and cultural contexts of the people and communities served (42) |

| Evidence-based spiritual care | • Based on personal experience, uses the best available evidence, and takes into account the specific needs, resources, and values of the patient or caregiver (28) |

| Formal spiritual Assessment | • Active listening to the story of a patient by a spiritual care professional, who summarizes the needs and resources that result from this process. This summary includes a plan of care that is shared with the rest of the team. Because of the complex nature of these assessments and the training required to conduct them, they should only be performed by a certified chaplain or equivalently trained professional (9) |

| Interdisciplinary team | • A model of synergistic and interdependent interaction of team members with specific competencies, which may include physicians, nurses, psychologists, spiritual care professionals, physical therapists, social workers, and other professionals and volunteers with the credentials, experience, and competencies (massage, art, and music therapy) (9) |

| Professional in spiritual care (Chaplain) | • Specialist on the interdisciplinary team who has undergone vocational training in meeting the spiritual and religious needs of patients and caregivers, regardless of his or her own spiritual beliefs and practices (9) |

| Religion | • Religion includes beliefs, practices, and rituals related to the sacred. It can be organized and practiced in the community or practiced in private. Religion originates from an established tradition that grows out of a community with common beliefs and practices. Religion is one way of expressing spirituality (9) |

| Religious care | • The care that a religious leader exercises for members of his or her own religious community. Unlike a spiritual care professional or spiritual advisor, religious professionals do not undergo specialized clinical training (11) |

| Spiritual history | • Use a series of questions to obtain the most relevant information about the patients’ and caregivers’ needs, hopes, and resources. The information obtained allows the clinician to understand how spiritual concerns can influence the general condition of the patient. Appropriate education should be provided about the situations that may arise and how to have these conversations in a comfortable way (9) |

| Spiritual screening | • A quick assessment of whether a person is experiencing a spiritual crisis and needs to be referred to specialist spiritual care. It helps identify which patients will benefit from a formal spiritual assessment. Screening is performed upon admission and at different times during care (9) |

| Spirituality | • The dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity that relates the way in which individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way in which they experience their connection with the moment, themselves, others, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is recognized as a fundamental aspect of patient- and family-centered compassionate palliative care (9) |

Table 2

| Spiritual care competencies | Observable behaviors |

|---|---|

| Competency 1: personal, spiritual, and professional development | • Articulate basic concepts related to religion, spirituality, spiritual suffering, and self-care |

| • Recognize the role of one’s own spirituality in one’s professional life | |

| • Recognize that the development of self-awareness prevents fears and prejudices from being barriers to patient care | |

| • Recognize burnout and compassion fatigue and activate prevention protocols when necessary | |

| • Plans and provide continuous education and training in spirituality for oneself and all team members | |

| • Develop and participate in spirituality research protocols | |

| Competency 2: ethics of spiritual care | • Recognize that self-care is necessary for quality and holistic care |

| • Recognize that spiritual care is centered on the person and their dignity | |

| • Share care planning with patients and families, respecting advance directives | |

| • Respect the autonomous decisions of patients and caregivers in every aspect of care | |

| • Recognize ethical dilemmas at the end of life and refer them to hospital bioethics committees if necessary; participate in hospital bioethics committees as needed | |

| Competency 3: spiritual needs assessment and spiritual care interventions | • Recognize that patients and caregivers may have differing spiritual needs and adjust the plan of care as needed |

| • Implement standardized spiritual history and screening tools according to local context | |

| • Establish and document protocols for general and specialized spiritual care | |

| • Identify and evaluate spiritual needs and resources and integrate them in the care plan at different stages of the disease until death | |

| • Adapt the plan of care to different cognitive, physical, visual, and hearing abilities and needs | |

| • Recognize spiritual needs at different stages of life (children, adolescents, adults, and seniors) and include them in the care plan | |

| • Respect the religious needs of patients, such as prayer, spiritual practices, celebration of holidays, and religious ceremonies | |

| • Identify the spiritual dimension of grief in patients and caregivers and refer to a specialist when necessary | |

| Competency 4: empathic and compassionate communication | • Develop empathetic listening and assertive and compassionate communication skills with patients and caregivers |

| • Document pertinent information for the team (screening, spiritual history, and care plan) in the clinical history, respecting confidentiality | |

| • Create spiritual care plans that include assessment, interventions, and objectives and present them in team meetings | |

| • Identify the cultural, social, and religious barriers that hinder communication within the institution | |

| Competency 5: supportive and collaborative relationships of the interdisciplinary team | • Be responsible for quality spiritual care |

| • Develop a clear protocol for quality spiritual care. Every member of the team knows his or her role, understands his or her professional limits, and refers patients to specialized spiritual care when appropriate | |

| • Identify a team member—ideally a spiritual care professional—who is responsible for coordinating and providing specialized spiritual care. Establish contacts and alliances with religious, spiritual, and cultural leaders in the community as valid resources to consider when necessary | |

| Competency 6: inclusivity and diversity | • Respect different expressions of spiritual, religious, cultural, and gender diversity, Spiritual care should include those who identify as atheist or agnostic or as having no specific faith |

| • Recognize and respect the main characteristics of different local cultures (native peoples, immigrants, and ethnic groups) | |

| • Promote an institutional environment that is inclusive of the cultural differences of patients, caregivers, and staff | |

| • Recognize that the cultural aspects of patients and families can influence medical decision-making | |

| • Recognize that spiritual care professionals’ own culture and beliefs influence professional practice, communication styles, and medical decision-making |

Based on these first guidelines, our focus group study discussed the literature in different steps and relevant competencies in quality spiritual care were identified and adapted to the Latin America setting through a consensus process with clinical spiritual care leaders, including all members of the Spirituality Commission of the ALCP (listed as authors in this manuscript) and three members of independent organizations who also contributed to this manuscript. These three individuals were Dr. Maria Mercedes Fajardo Sanmartin, who is the Coordinator of Pain and Palliative Care Service at Clínica Imbanaco, Grupo Quirón Salud in Cali, Colombia; José Luis Martínez, who is the Spiritual Care Director of Hospital Universitario San Ignacio in Bogotá, Colombia; and Dr. Andrea Valverde Vega, palliative care specialist and Coordinator of the Spirituality Commission of Centro Nacional de Control del Dolor y Cuidados Paliativos in San Jose, Costa Rica.

In the final step in this process, the members of the commission held five educational sessions in which each competency was further analyzed and discussed to reach a final consensus on Quality Spiritual care in our region. The final document created was approved by the board members of the ALCP and was presented to the ALCP general members during the second Latin American Symposium of Spirituality in Palliative Care on October 16, 2020.

Results

We identified six core competencies of quality clinical spiritual care in Latin America: (I) personal, spiritual, and professional development; (II) ethics of spiritual care; (III) assessment of spiritual needs and spiritual care interventions; (IV) empathic and compassionate communication; (V) supportive and collaborative relationships among the interdisciplinary team; and (VI) inclusivity and diversity (Figure 1). We also described observable behaviors that can be used as guidance for teams in Latin America that wish to include or strengthen evidence-based spiritual care in their practices.

Competency 1: personal, spiritual, and professional development

Personal, spiritual, and professional development describes the ability of each team member to recognize the impact of their own beliefs, attitudes, and preferences on the spiritual care of patients and their caregivers. Developing and maintaining appropriate personal, spiritual, and professional growth are important to providing spiritual care focused on patients’ and caregivers’ needs (9,20,25).

In this competency, the observed behaviors of the team members consist of the following:

- Articulating concepts such as religion, spirituality, spiritual and existential suffering, self-care, and quality spiritual care in the clinical setting;

- Recognizing that one’s own spirituality, that allow us to have continuous Spiritual growth (which includes the entire human experience in the search for meaning and purpose and connections with themselves and others, and is not limited to religion) plays an important role in one’s professional life and the need to develop it using appropriate self-reflection tools in one’s professional practice;

- Recognizing the importance of self-care as conscious acts to stay physically, emotionally and spiritually balanced and connected with ourselves and with others and the continuous development of self-awareness and self-reflection allows one to avoid one’s own fears, prejudices, and limitations that create barriers to care and maintaining an attitude of critical reflection regarding one’s clinical spiritual care practice;

- Recognizing the signs of burnout syndrome, compassion fatigue, and chronic stress in oneself and others and activating established protocols within the team to address these issues;

- Establishing an ongoing plan to nurture one’s own spirituality, compassionate presence, and self-reflective capacity;

- Establishing a continuous academic education plan to develop and strengthen the competencies needed to provide quality spiritual care based on clinical evidence;

- Launching active support and consultation networks for spiritual, personal, and professional development;

- Leading and supporting teams in promoting performance and professional growth in the spiritual aspect of care and optimizing the skills of the team to meet the current and future spiritual care needs of the healthcare system;

- Developing and participating in research and quality improvement protocols to address various issues related to spiritual care in clinical settings;

- Basing spiritual care on scientific evidence-based practices and adapting to the local context.

Competency 2: ethics of spiritual care

The ethics of spiritual care describes the duty to respect human life in all its manifestations from the moment of conception to death according to the principles of autonomy, substituted judgement, beneficence and non-maleficence. Following these principles in each of its interactions and interventions, the team should respect the human condition and the dignity of every person. This respect for life is inextricably linked with acceptance of the vulnerability and essential fragility of each person, especially during the trajectory of a life-threatening illness (9).

In this competency, the observed behaviors of the team members consist of the following:

- Recognizing that ethical spiritual care is centered on the person and respecting his or her dignity;

- Understanding that the team has an ethical obligation to respect and meet the spiritual needs of patients and their caregivers;

- Recognizing self-care as an ethical necessity in quality holistic care;

- Sharing the care plan with the patient and caregivers so that they can identify their treatment preferences according to their cultural values and taboos; these indications are respected in advance directives;

- Recognizing ethical dilemmas related to spiritual and religious needs in palliative care, with a special emphasis on the end of life, and referring cases to hospital ethics committees if necessary;

- Participating in hospital ethics committees to represent the spiritual needs of patients and caregivers;

- Identifying and addressing situations in the health system or organization that may affect human dignity and the human right to medical care;

- Not imposing team members’ own visions of spirituality and religion, including respecting the autonomous decisions of patients and caregivers to not receive spiritual care.

Competency 3: assessment of spiritual needs and spiritual care interventions

Assessment of spiritual needs and spiritual care interventions describes the ability of each team member to recognize the immediate spiritual crises and needs of patients and caregivers (spiritual screening) and to identify spiritual frameworks, needs, and resources (spiritual history) (7,9,23,29). It also describes general spiritual care interventions and recognizes the differences between general and specialized spiritual care (7,9-15,17,20,23-25,43).

In this competency, the observed behaviors of the team members consist of the following:

- Recognizing the importance of spiritual care in palliative care and receiving the necessary support and education to respond to the spiritual needs of patients and caregivers;

- Identifying, evaluating, and documenting the spiritual needs and resources that arise throughout the course of an illness; integrating them into the palliative care plan; and establishing a follow-up plan for the family after the death of their loved one;

- Implementing a standardized spiritual history and screening tools that are tailored to the local clinical and cultural setting;

- Implementing general spiritual care interventions based on assessment of resources and the spiritual needs of patients and caregivers;

- Establishing and documenting a spiritual care protocol that ensures that patients and caregivers receive continued general and specialized spiritual care according to their needs. All members of the interdisciplinary team should recognize their roles in this plan;

- Recognizing that the spiritual needs of caregivers may be different from those of patients and establishing a plan of care according to these needs;

- Recognizing that an integral part of quality spiritual care is responding to the religious needs of patients, such as prayer, spiritual practices, holiday celebrations, and religious ceremonies and rituals. Spiritual care specialists offer this type of care according to their training or religious affiliation or coordinate the necessary intervention with trained religious leaders;

- Recognizing the spiritual needs of people at different stages of life and with different levels of cognitive development (children, adolescents, adults, and older adults) and implementing or coordinating general spiritual interventions according to age and need;

- Recognizing one’s professional limits in terms of ability to offer general spiritual care and referring patients to suitable personnel for specialized spiritual care;

- Identifying spiritual and religious resources for patients and caregivers at the end of life that can support the grieving process;

- Identifying and recognizing the spiritual dimension of grief and its different manifestations in patients and caregivers and referring them to appropriate specialists.

Competency 4: empathic and compassionate communication

Empathic and compassionate communication describes the ability to communicate effectively with the team and members of the clinical institution to respond to the spiritual needs of patients and caregivers according to reporting, documentation, professional, legal, and ethical requirements (9,16,44). Empathic and compassionate communication with patients, family, and caregivers is essential for quality spiritual care.

In this competency, the observed behaviors of the team members consist of the following:

- Demonstrating active and empathic listening skills and assertive and compassionate communication strategies with patients and caregivers regarding spiritual issues;

- Documenting spiritual screening, history and plans of spiritual care in the medical record, balancing the need for confidentiality and privacy with the need to share pertinent information with the team. Each member of the team must have relevant information to carry out spiritual care;

- Identifying and accounting for cultural, social, and religious barriers that hinder effective communication. When necessary, interpreters and appropriate cultural and religious services should be used;

- Documenting and sharing a spiritual care plan in team meetings that includes scheduled interventions, desired objectives, and methods of evaluating the effectiveness of interventions;

- Adequately explaining the scope of quality spiritual care as part of the palliative care plan to patients, caregivers, and clinicians in the institution.

Competency 5: supportive and collaborative relationships of the interdisciplinary team

Supportive and collaborative relationships among the interdisciplinary team members define the team’s ability to create and maintain collaborative and mutually committed relationships with one another and with administrative staff, external organizations, and community partners to provide quality spiritual care (13-16,22).

In this competency, the observed behaviors of the team members consist of the following:

- Each palliative care team should include a professional who is responsible for providing and coordinating spiritual care. If a spiritual care specialist/professional or spiritual counselor is not available, this role can be temporarily assumed by a member of the team who is fully trained in the competencies for high quality spiritual care, as described in this document;

- The spiritual care leader recognizes the contribution of each discipline and integrates it into the care plan to provide quality spiritual care for patients and their caregivers;

- Spiritual care professionals know how to work in a team and are familiar with the theoretical bases for interdisciplinary work. They practice and continually develop the basic skills needed for this type of work;

- The team members recognize that various conflicts arise in interdisciplinary work that must be identified and resolved to provide quality spiritual care;

- Spiritual care professionals establish contacts and alliances with religious, spiritual, cultural, and community leaders who can serve as resources to meet the specific needs of patients and caregivers.

Competency 6: inclusivity and diversity

Inclusivity and diversity describe the ability to recognize the sociocultural factors relevant to the patient, caregivers, team, and clinical institution that influence treatment and care throughout the course of an illness and are essential to creating an inclusive environment that is respectful of differences observed in our population (9,40,42,45,46).

In this competency, the observed behaviors of the team members consist of the following:

- Establishing processes to ensure that spiritual care is respectful of the spiritual, religious, cultural, and gender identity and diversity of patients and their caregivers at different stages of life as well as hospital staff. Spiritual care should include that for patients who are atheist or agnostic and those who do not identify with a specific faith;

- Providing spiritual care to all people regardless of diagnosis or clinical condition;

- Knowing the main characteristics of different local cultures that may influence spiritual care (e.g., native people, immigrants, ethnic groups);

- Promoting an institutional environment that is respectful and inclusive of the religious, cultural, and spiritual preferences of patients, caregivers, and hospital staff;

- Evaluating and addressing the cultural aspects of end-of-life care, including cultural rituals and beliefs related to the dying process, death and after death;

- Recognizing that the cultural aspects of patients and their caregivers can influence the medical decision-making process;

- Recognizing that one’s own culture and beliefs influence one’s professional practice when handling information and making clinical decisions;

- Identifying and resolving conflicts based on different cultural values and beliefs among patients, caregivers, and healthcare personnel.

Discussion

Herein we provide the first description of six core competencies for quality clinical spiritual care in Latin America. Many healthcare professionals may be unaware of the spiritual dimension in their own lives and therefore may have difficulty engaging in spiritual reflection, which is a professional requirement for better understanding the spiritual needs of their patients (7). Accepting our own vulnerability and spiritual needs allows us to improve the quality of our compassionate presence and listening in clinical encounters and recognizing that our own self-care is essential to provide quality spiritual care is important. We must also be aware that caring for people who are experiencing existential suffering at the end of their lives can become an opportunity for personal spiritual transformation (15).

Healthcare professionals who work in teams that care for patients with advanced or terminal illnesses in distress are at risk for progressive and deteriorating stress, which may result in compassion fatigue or burnout syndrome (20,47). Because of the existence of personal, organizational, and institutional risk factors for compassion fatigue and burnout, a team must develop tools for self-care strategies for healthcare professionals and caregivers as well as other tools for preventing this stress (9,19).

The importance of spiritual care in palliative care highlights the importance of developing leadership capacity in the field of spirituality and to promote this field among all health professionals and administrators (7,24). Spiritual care leadership is necessary to continue the implementation of general and professional spiritual care by teams, strengthen the spiritual care research environment, and improve evidence-based education on spiritual care in all disciplines.

Clinical spiritual care is centered on and directed by patients and caregivers. Clinicians must become competent in the care of patients and caregivers with the different ethnic, cultural, and religious groups in their local areas and identify the various values, cultural aspects, and specific spiritual and religious preferences and integrate them into the care plan (9,42). Therefore, the team has an ethical obligation to establish adequate relationships with patients and caregivers through a compassionate presence and attentive listening, respect their beliefs, and accept their decision to reject any type of spiritual support that does not meet their needs (9).

The wishes and needs of patients and caregivers may conflict with clinicians’ beliefs and values or their obligations to their religious traditions. In such cases, considering that the patient’s needs should guide spiritual interventions, the provision of spiritual care should be referred to another person (7). The team members have an ethical responsibility to determine when organizational structures and systems create situations in which human dignity, human rights, or patient preferences are violated and take the necessary corrective measures (25,48).

Spirituality is a dimension common to all people, and having an advanced disease places a patient in a challenging situation in which fundamental spiritual and existential questions arise. Spiritual care is a continuous process that requires presence and attentive listening in a climate of deep respect for the spiritual needs of patients and their families, as they may be different (9). Team members should listen to, evaluate, and attend to patients’ spiritual needs, referring them to specialists when needed (7,9,13-15). A patient’s spirituality must always be addressed during the course of the disease, not just at the end of life (7). When starting relationships with patients and caregivers, it is fundamental to respect and acknowledge their coping pace and accept their possible acceptance or declining of spiritual care, team members should continue to accompany them through their journey, as patients and caregivers may need spiritual care under different circumstances or at other stages of their illnesses (7,9,49,50).

Healthcare professionals should adopt and implement structured and validated instruments of spiritual assessment to facilitate the documentation of spiritual needs and evaluate the outcomes of spiritual interventions (7,9,21,23,43). We recognize also that tools used in other countries will need to be validated in the Latin American context. The goal of spiritual screening is to identify the presence of a spiritual or existential crisis and immediate spiritual needs (7,9). Simple questions that can be used in a spiritual screening tool by any member of the interdisciplinary team include “Are you at peace?” (23), “Do you have spiritual pain (pain deep in your soul or being that is not physical)?” (51), and “Are religion and spirituality important to you as you cope with your illness, and if so, how much do they help you at this time?” (52). Although such screening tools serve to guide spiritual screening, there is need to validate them and proof their effectiveness in the Latin America context.

Spiritual history tools use more questions to help capture the spiritual and religious history of patients and caregivers (7,9,23) and can be used by any member of the interdisciplinary team in clinical assessment at admission. Among the best known tools in the Latin American context are: the GES questionnaire (an assessment of spiritual resources and spiritual needs and facilitating intervention with palliative care patients) (53); the Faith, Importance and Influence, Community, and Address Spiritual History Tool (FICA) (54); and the Escala Numérica para evaluar Síntomas Espirituales en Cuidados paliativos (ENESE) (a numerical scale used to assess spiritual symptoms) (55). The spiritual dimension in children and adolescents should be considered in light of their developmental stages so that spiritual care is respectful of their needs and concerns (9,56,57).

A patient’s spiritual history should be included in the healthcare treatment plan after identifying spiritual needs, resources, and appropriate interventions with clear and precise goals to improve the quality of life of the patients and caregivers (58). Spiritual care professionals must be trained to plan, provide spiritual care and facilitate prayers, practices, rituals, ceremonies, and religious services, including funerals and celebrations related to religious holidays (25). The religious needs of the patient and/or caregivers should be met by a religious leader from their own community when requested (7,9,12,42).

Spiritual care depends on the ability to establish an effective connection with the patient or caregiver. Healthcare professionals must recognize the most frequent barriers to communication and use basic tools and resources for effective communication (such as spoken or sign language interpreters or a person familiar with the patient’s culture) to overcome barriers related to the end of life, planning of care, prognosis, and expectations of care (42). The spiritual care provider must communicate to the team any information obtained during the spiritual assessment that may affect the patient’s medical care (7). To respect the patient’s confidentiality and privacy, determining the type of information that the entire team (or specific team members) must know to provide care is necessary; concealing specific details that may violate the patient’s trust or confidentiality is important (7).

One of the most common barriers to providing quality spiritual care is discomfort of healthcare professionals when initiating conversations about spirituality (11,12,14,59-61). Being able to effectively communicate the scope and benefits of spiritual care in the context of health care is essential for helping patients and caregivers understand and accept this type of care. All team members should know how to explain the basic concepts of spiritual care (e.g., describing the difference between spirituality and religion) and initiate a general dialogue to identify basic spiritual needs and resources (25,49,62).

Conflicts are natural parts of interpersonal relationships that influence communication with patients and caregivers and with other team members, affecting the ability to provide quality spiritual care. Therefore, each team member should identify and implement methods of conflict resolution and effective communication (63-65).

Teamwork with a shared philosophy and common goals is the main tool needed to provide a holistic approach to ensuring quality spiritual care for patients and their caregivers (7,9,15,16). Understanding and respecting one’s own professional limits and recognizing how and when to refer patients to specialists for spiritual care consultations and interventions are important (7,9,11,14,19,20,62,63). Also important is facilitating patients’ and caregivers’ access to pastors, religious leaders, and traditional healers in their community. Establishing such collaborative networks and relationships facilitates quality spiritual care for patients and caregivers in the clinical setting and may be associated with increased levels of patients’ health care satisfaction (7,9,12,39).

For some patients and caregivers, following cultural and religious practices during treatment is important. Clinical staff should be prepared to allow family visits, family collaboration in patient care and hygiene, rituals such as meditation and prayer, and rituals related to food. Good communication that clarifies health standards and what is allowed in the clinical context avoids conflicts, improves the well-being of patients and caregivers, and facilitates the work of the clinical staff (7).

In addition to being documented in the patient’s medical history, the information obtained in spiritual assessments should be shared in team meetings. This will ensure that all members are aware of the patient’s spiritual needs and strengths that are relevant to treatment.

Patients and caregivers of minority sexual orientations or gender identities may have had negative experiences related to religious and sociocultural tolerance. A responsibility of team members is to ensure that these individuals experience respectful and inclusive quality spiritual care that is responsive to their specific needs and honors their human worth and dignity (66).

Cultural and religious majorities may make the spiritual needs of minorities invisible. This can occur in institutions affiliated with a specific religious community where the needs of people of minority religions or who identify as atheist or agnostic might not be considered. It can also occur in secular institutions where the religious or spiritual needs of patients or caregivers might not be considered. Ensuring that the religious symbols and language used at the professional and institutional level are inclusive and respectful of everybody is important (9).

Spiritual care must also take into account the needs of people with different cognitive, physical, visual, or hearing abilities. Thus, languages and interventions must be adapted to meet different needs (9,67).

In carrying out spiritual care activities, the team must recognize and respect the different spiritual, religious, and cultural traditions of its own members. Furthermore, healthcare professionals must be aware of their own cultural and religious beliefs and values. This awareness is necessary to minimize the possibility that prejudices, or personal preferences interfere with the interprofessional and caregiving relationships among people who have different values or beliefs (7,9,20).

We recognize that this article is not without limitations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published article on competencies regarding the quality of spiritual care in Latin America. We believe that a more rigorous, consensus approach about Latin America quality spiritual care competencies must be taken to include more perspectives and experiences relevant to our reality and experiences. Also, we recognize that given the different settings in which palliative care is provided in Latin America, not all teams will be able to develop these competencies in a short period. Our hope is that this article will mark the beginning of not only a conversation about but also an action plan toward integrating and adopting high standards in spiritual care for the benefit of all health care teams and for the high-quality care of patients and caregivers in Latin America. At the same time, to help developing high quality educational programs and research about different aspects of spirituality, considering different cultural, social, and religious expressions impact decision making, quality of life, symptom expression, and coping mechanisms in our region.

Conclusions

We identified six essential competencies that every member of an interdisciplinary palliative care team needs to provide quality spiritual care and thus improve the overall care and quality of life for patients and their caregivers and to facilitate the systematization of multidisciplinary educational programs and research protocol about different aspects of Spiritual Care in Latin America.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Editing Services, Research Medical Library at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for editorial assistance.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-519/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-519/coif). MODG serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Palliative Medicine from April 2022 to March 2024. MODG is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (No. R01 CA200867). This study did not have any funding. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ong CK, Forbes D. Embracing Cicely Saunders's concept of total pain. BMJ 2005;331:576. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fajardo-Chica D. Sobre el concepto de dolor total. Revista de Salud Pública 2020;22:1-5. [Crossref]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course [Internet] Geneve: World Health Assembly; 2014 [cited 2022 Aug 11] Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/162863

- Acuña W. La luz de la bioética en la atención espiritual [Internet] Madrid:Universidad Pontificia Comillas; 2014 [Cited 2022 Aug 11] Available online: https://repositorio.comillas.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11531/2732/TFM000045.pdf?sequence=1

- Gilligan C. La ética del cuidado. [Internet] Barcelona: Fundación Victor Grifols I Lucas; 2013 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://www.fundaciogrifols.org/en/web/fundacio/-/la-etica-del-cuidado

- Benito E, Barbero J, Dones M, et al. Espiritualidad en Clínica: Una propuesta de evaluación y acompañamiento espiritual en Cuidados Paliativos [Internet]. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL); 2014 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://espiritualidadpamplona-irunea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Espiritualidad-en-cuidados-paliativos.pdf

- Best M, Leget C, Goodhead A, et al. An EAPC white paper on multi-disciplinary education for spiritual care in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC). [Internet] Houston: Global Consensus based palliative care definition; 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://hospicecare.com/uploads/2018/12/Palliative%20care%20definition%20-%20English.pdf

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th edition. [Internet] Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp

- Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL). Libro Blanco sobre normas de calidad y estándares de cuidados paliativos de la sociedad Europea de Cuidados Paliativos [Internet] Madrid: Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL); 2012 May [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: http://www.cuidarypaliar.es/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Libro-blanco-sobre-normas-de-calidad-y-est%C3%A1ndares.-Monograf%C3%ADas-SECPAL.-2012.pdf

- Marin D, Vansh S, Powers R, et al. Spiritual Care and Physicians: Understanding Spirituality in Medical Practice [Internet] Health Care Chaplaincy Network; 2017 Sept [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://spiritualcareassociation.org/docs/resources/hccn_whitepaper_spirituality_and_physicians.pdf

- Delgado-Guay MO. Spirituality and religiosity in supportive and palliative care. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2014;8:308-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. La mejora de la calidad de los cuidados espirituales como una dimensión de los cuidados paliativos: el informe de la Conferencia de Consenso. Medicina Paliativa 2011;18:20-40. [Crossref]

- Puchalski CM, Sbrana A, Ferrell B, et al. Interprofessional spiritual care in oncology: a literature review. ESMO Open 2019;4:e000465. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Luis V, Dones M, Martinez R, et al. El Acompañamiento Espiritual en los Equipos de Cuidados Paliativos. Trabajo en equipo y acompañamiento espiritual. In: Benito E, Dones M, Barbero J, editors. Espiritualidad en Clínica: Una propuesta de evaluación y acompañamiento espiritual en Cuidados Paliativos [Internet]. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL), 2014:147-60. Available online: https://espiritualidadpamplona-irunea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Espiritualidad-en-cuidados-paliativos.pdf

- Gamondi C, Larkin P, Payne S. Core competencies in palliative care Part I: an EAPC White Paper on Palliative Care Education part 1. Eur J Palliat Care 2013;20:86-91.

- Gijsberts MHE, Liefbroer AI, Otten R, et al. Spiritual Care in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of the Recent European Literature. Med Sci (Basel) 2019;7:25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Health Care Chaplaincy Network (HCCN). The Chaplaincy Taxonomy: Standardizing Spiritual Care Terminology [Internet]. Health Care Chaplaincy Network; 2019 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://sdcoalition.org/wordpresssite/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/taxonomy-for-chaplains.pdf

- International Association for Palliative Care (IAHPC). Competencias en Cuidados Paliativos en Educación de Pregrado. Resumen de recomendaciones consensuadas [Internet]. Cali, Colombia: International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2015 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://docplayer.es/19837951-Transformando-el-sistema-competencias-encuidados-paliativos-en-educacion-de-pregrado-en-colombia.html

- Gamondi C, Larkin P, Payne S. Core competencies in palliative care Part II: an EAPC White Paper on Palliative Care Education. European Journal of Palliative Care 2013;20:140-5.

- Esperandio M, Leget C. Espiritualidad en los cuidados paliativos: ¿un problema de salud pública? Rev Bioét 2020;28:543-53. [Crossref]

- Steinhauser KE, Fitchett G, Handzo GF, et al. State of the Science of Spirituality and Palliative Care Research Part I: Definitions, Measurement, and Outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;54:428-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balboni TA, Fitchett G, Handzo GF, et al. State of the Science of Spirituality and Palliative Care Research Part II: Screening, Assessment, and Interventions. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;54:441-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Guay MO, Palma A, Duarte E, et al. Association between Spirituality, Religiosity, Spiritual Pain, Symptom Distress, and Quality of Life among Latin American Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Multicenter Study. J Palliat Med 2021;24:1606-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manitoba’s Spiritual Health Care Partners. Core Competencies for Spiritual Health Care Practitioners [Internet]. Manitoba: Interfaith Health Care Association of Manitoba; 2017 Sep [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.ihcam.ca/media/Presentations/Core-Competencies-for-Spiritual-Health-Care-Practitioners-2017.pdf

- Murphy P, Fitchett G. Introducing Chaplains to Research: “This Could Help Me” J Health Care Chaplain 2010;16:79-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruiz C, Jimenez E, Cabodevilla I, et al. Formación en Acompañamiento Espiritual: Algunas experiencias. In: Benito E, Dones M, Barbero J. editors. Espiritualidad en Clínica Una propuesta de evaluación y acompañamiento espiritual en Cuidados Paliativos [Internet]. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL), 2014:177-89.

- Fitchett G, Nieuwsma JA, Bates MJ, et al. Evidence-based chaplaincy care: attitudes and practices in diverse healthcare chaplain samples. J Health Care Chaplain 2014;20:144-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galiana L, Oliver A, Barreto P. Recursos en Evaluación y Acompañamiento Espiritual: Revisión de medidas y presentación del cuestionario GES. In: Benito E, Dones M, Barbero J. editors. Espiritualidad en Clínica Una propuesta de evaluación y acompañamiento espiritual en Cuidados Paliativos. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL), 2014:131-45.

- Pastrana T, De lima L, Sánchez-Cárdenas M, et al. Atlas de Cuidados Paliativos en Latinoamerica [Internet]. Houston: IAHPC Press; 2021 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://cuidadospaliativos.org/recursos/publicaciones/atlas-de-cuidados-paliativos-de-latinoamerica/

- Pérez-Cruz PE, Langer P, Carrasco C, et al. Spiritual Pain Is Associated with Decreased Quality of Life in Advanced Cancer Patients in Palliative Care: An Exploratory Study. J Palliat Med 2019;22:663-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. Religión en America Latina: cambio generalizado en una región históricamente católica. [internet]. Washington: Pew Research Center, 2014 Nov 13 [cited 2020 Aug 11]; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2014/11/PEW-RESEARCH-CENTER-Religion-in-Latin-America-Overview-SPANISH-TRANSLATION-for-publication-11-13.pdf

- Naciones Unidas, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe.(CEPAL). Los pueblos indígenas en América Latina: Avances en el último decenio y retos pendientes para la garantía de sus derechos [Internet]. Santiago: Comisión Económica para America Latina (CEPAL), Naciones Unidas 2014 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/37050

- Latinobarometro [Internet]. Santiago de Chile: Análisis Online; 2021 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://www.latinobarometro.org/latOnline.jsp

- Murrell NS. Afro-Caribbean Religions: An Introduction to Their Historical, Cultural, and Sacred Traditions. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010.

- Pagano A. Afro-Brazilian Religions and Ethnic Identity Politics in the Brazilian Public Health Arena. Health Culture and Society 2012;3:1-28. [Crossref]

- Blancarte R. Diccionario de religiones en América Latina. 1st Ed. Mexico D.F: Fondo de Cultura Económica, El Colegio de México, 2018.

- Bautista-Valarezo E, Duque V, Verhoeven V, et al. Perceptions of Ecuadorian indigenous healers on their relationship with the formal health care system: barriers and opportunities. BMC Complement Med Ther 2021;21:65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bautista-Valarezo E, Duque V, Verdugo Sánchez A, et al. Towards an indigenous definition of health: an explorative study to understand the indigenous Ecuadorian people’s health and illness concepts. Int J Equity Health 2020;19:101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- López-Sierra HE. Cultural Diversity and Spiritual/Religious Health Care of Patients with Cancer at the Dominican Republic. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2019;6:130-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asociación Latinoamericana de Cuidados Paliativos (ALCP) [Internet]. Bogotá: Comisión de Espiritualidad; c2022 [cited 2022 Aug 11] Available online: https://cuidadospaliativos.org/quienes-somos/comisiones-de-trabajo/espiritualidad/

- The Joint Commission International. Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals. [Internet] Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission, 2010. [Cited 2022 Aug 11] Available online: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/aroadmapforhospitalsfinalversion727pdf.pdf?db=web&hash=AC3AC4BED1D973713C2CA6B2E5ACD01B&hash=AC3AC4BED1D973713C2CA6B2E5ACD01B

- Espinel J, Colautti N, Reyes M; Comisión de Espiritualidad. Competencias para el Cuidado Espiritual de Calidad en Cuidados Paliativos. [Internet].Bogota: Asociación Latinoamericana de Cuidados Paliativos, Comisión de Espiritualidad; 2020 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://cuidadospaliativos.org/uploads/2020/10/Competencias%20Cuidado%20Espiritual.pdf

- Goldstein R. Chapter 6: Chaplains and Charting. In: Roberts S. editor. Professional Spiritual & Pastoral Care: A Practical Clergy and Chaplain’s Handbook. Kindle Edition. Woodstock, VT: Skylight Paths Publishing, 2012.

- Johnstone MJ, Kanitsaki O. Ethics and advance care planning in a culturally diverse society. J Transcult Nurs 2009;20:405-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schim SM, Doorenbos AZ. A three-dimensional model of cultural congruence: framework for intervention. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2010;6:256-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benito E, Sansó N, Pades A, et al. El Profesional Como Herramienta de Acompañamiento: La autoconciencia como clave del autocuidado. In: Benito E, Dones M, Barbero J, editors. Espiritualidad en Clínica Una propuesta de evaluación y acompañamiento espiritual en Cuidados Paliativos. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL), 2014:163-75.

- Osman H, Shrestha S, Temin S, et al. Palliative Care in the Global Setting: ASCO Resource-Stratified Practice Guideline. J Glob Oncol 2018;4:1-24. [PubMed]

- Selman LE, Brighton LJ, Sinclair S, et al. Patients’ and caregivers’ needs, experiences, preferences and research priorities in spiritual care: A focus group study across nine countries. Palliat Med 2018;32:216-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillilan R, Qawi S, Weymiller AJ, et al. Spiritual distress and spiritual care in advanced heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2017;22:581-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mako C, Galek K, Poppito SR. Spiritual pain among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1106-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fitchett G, Murphy P, King SDW. Examining the Validity of the Rush Protocol to Screen for Religious/Spiritual Struggle. J Health Care Chaplain 2017;23:98-112. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL). Cuestionario GES: Evaluación de recursos y necesidades espirituales [Internet]. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL); 2014 [cited Aug 11, 2022] Available online: https://www.redpal.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Cuestionario-GES.pdf

- Clinical FICA tool [Internet]. Washington: The GW Institute for Spirituality and Health 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 11]. Available online: https://gwish.smhs.gwu.edu/programs/transforming-practice-health-settings/clinical-fica-tool

- Reyes MM, de Lima L, Taboada P, et al. A scale to assess spiritual symptoms in palliative care. Rev Med Chil 2017;145:747-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nash P, Roberts E, Nash S, et al. Adapting the Advocate Health Care Taxonomy of Chaplaincy for a Pediatric Hospital Context: A Pilot Study. J Health Care Chaplain 2019;25:61-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sommer D. Chapter 20: Pediatric Chaplaincy. In: Roberts S. editor. Professional Spiritual & Pastoral Care: A Practical Clergy and Chaplain’s Handbook Kindle Edition. Woodstock, Vt: Skylight Paths Publishing, 2012.

- Peery B. Chapter 27: Outcome Oriented Chaplaincy: Intentional Caring. In: Professional Spiritual & Pastoral Care: A Practical Clergy and Chaplain’s Handbook. Kindle Edition. Woodstock, VT: Skylight Paths Publishing, 2012.

- Puchalski CM, Lunsford B, Harris MH, et al. Interdisciplinary spiritual care for seriously ill and dying patients: a collaborative model. Cancer J 2006;12:398-416. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salas C, Taboada P. Espiritualidad en medicina: análisis de la justificación ética en Puchalski. Rev méd Chile 2019;147:1199-205. [Crossref]

- Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Enzinger AC, et al. Nurse and physician barriers to spiritual care provision at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:400-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poncin E, Niquille B, Jobin G, et al. What Motivates Healthcare Professionals' Referrals to Chaplains, and How to Help Them Formulate Referrals that Accurately Reflect Patients' Spiritual Needs? J Health Care Chaplain 2020;26:1-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. [Internet] Washington, DC. Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011 [cited 2022 Aug 11]; Available online: https://www.aacom.org/docs/default-source/insideome/ccrpt05-10-11.pdf

- Davis K. Understanding The Importance Of The Interdisciplinary Team In Pediatric Hospice And Palliative Care. [Internet]. Alexandria, VA. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; 2018 [cited 2022 Aug 11]; Available online: https://www.nhpco.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/04/PALLIATIVECARE_UnderstandingIDT.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO). Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 [cited 2022 Aug 11] Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70185/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Anderson N. Chapter 22: Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgendered (GLBT) People. In: Professional Spiritual & Pastoral Care: A Practical Clergy and Chaplain’s Handbook. Kindle Edition. Woodstock, Vt: Skylight Paths Publishing, 2012.

- Gaventa B. Chapter 23: Spiritual/Pastoral Care with People with Disabilities and Their Families. In: Professional Spiritual & Pastoral Care: A Practical Clergy and Chaplain’s Handbook. Kindle Edition. Woodstock, VT: Skylight Paths Publishing, 2012.