Current situation and support need for non-cancer patients’ admission to inpatient hospices/palliative care units in Japan: a nationwide multicenter survey

Highlight box

Key findings

• A total of 15.2% of facilities had admitted non-cancer patients, and 59.1% of the facilities were willing to accept the admission of non-cancer patients, assuming that hospitalization costs were covered by health insurance to the same level as cancer patients.

What is known and what is new?

• Specialist palliative care for non-cancer patients is important; however, access to inpatient hospices/palliative care units (PCUs) for non-cancer patients in Japan may be insufficient.

• Health insurance system in which appropriate palliative care is available regardless of disease, the definition of admission criteria, and the establishment` of a systematic educational program are important to improve the access to the specialist palliative care for non-cancer patients.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The establishment of a health insurance system in which appropriate palliative care is available regardless of disease, clarification of the admission criteria, and a systematic education program would improve the access to the specialist palliative care for non-cancer patients.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) stated that palliative care should be provided to all patients with serious illness and their families as part of universal health coverage (1). Moreover, the WHO reported that the majority of patients with palliative care needs are non-cancer patients (1); yet, palliative care has only recently been provided to non-cancer patients and their families (2-5). Previous studies reported that non-cancer patients experienced significantly more physical and psychological symptoms than cancer patients (6,7).

Japan’s universal health insurance system is based on a system in which individuals and the government share the cost of medical care and pay medical institutions. In 1990, a system of payment of fees for hospitalization in inpatient hospices/palliative care unit (PCU) was established under the universal health insurance system. Patients eligible for payment are mainly those in the terminal stages of cancer.

A systematic review reported that hospital-based specialist palliative care (HSPC), which includes inpatient hospices/PCUs and palliative care teams, reduced patient symptom burden, improved health-related quality of life, other person-centered outcomes, and satisfaction of patients with advanced illness (8). In spite of these clear advantages, inpatient hospices/PCUs have not committed to providing palliative care to non-cancer patients in Taiwan (9). This trend is similar in Japan where specialist palliative care has mainly been developed for advanced cancer patients in the last two decades (10).

Although the proportion of non-cancer patients among all deaths was 72.7% in Japan, the current situation of specialist palliative care for non-cancer patients is not well known, which comprises admission to inpatient hospices/PCUs, as well as the willingness to admit non-cancer patients to inpatient hospices/PCUs and the institutions’ support needs.

We aimed to explore the current situation of non-cancer patients’ admission to inpatient hospices/PCUs, the support needs to accept admission of non-cancer patients, and the willingness to accept admission of non-cancer patients to inpatient hospices/PCUs in Japan. These data may be important for expanding the provision of palliative care beyond cancer in Japan and would provide useful evidence for further service development in other countries. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-743/rc).

Methods

This study was a nationwide multicenter questionnaire survey targeting inpatient hospices/PCUs in Japan. We recruited potential participants from the 381 inpatient hospices/PCUs that were members of Hospice Palliative Care Japan (HPCJ) before December 12, 2021. HPCJ was established in 1991 and is the oldest palliative care organization in Japan, with more than 90.0% of all inpatient hospices and PCUs in Japan belonging to the organization.

Participants and procedures

The questionnaires were sent by post to each facility along with an explanation of the survey. The return of the completed questionnaire was regarded as consent to participate in the study. We asked the director of the physicians of the inpatient hospices/PCUs to complete the questionnaire and return it to the study secretariat office (University of Tsukuba) within 2 weeks. We sent a reminder to all participants 3 weeks after sending the questionnaire. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The Institutional Review Board of the University of Tsukuba (No. 1691) approved the protocol of this study.

Questionnaire

There is an absence of specific and validated instruments for evaluating the willingness to admit non-cancer patients to inpatient hospices/PCUs and the institutions’ support needs. Thus, we developed a draft questionnaire based on data from a previous study, a public health model, and discussion among the authors of the present study (11-13). To confirm content validity, we asked for feedback on modifying or adding questions to the draft questionnaire from five palliative care physicians, one psycho-oncologist, two palliative care research nurses, one specialized palliative care nurse, and one social worker, who were all from different institutions. All researchers (JH, YK and YS) revised the draft questionnaire based on feedback, and the face validity of the draft questionnaires was confirmed by ten palliative care physicians, all of whom were from different institutions, in October 2021. All researchers (JH, YK and YS) then modified the questionnaire to simplify the wording and to make misunderstandings less likely.

The questionnaire was composed of two parts. The first was the background characteristics of each facility: the number of beds in the hospital and inpatient hospices/PCUs, the percentage of cancer and non-cancer patient admissions that were referred from other hospitals in the fiscal year 2020 (April 2020 to March 2021), and the number of non-cancer patients [chronic heart failure (CHF), chronic respiratory failure, chronic hepatic failure, chronic renal failure (CRF) without dialysis, CRF with dialysis, intractable neurological disease, and dementia] admitted in fiscal year 2020.

The second was (I) about the necessity of coverage of hospitalization costs of non-cancer patients by the health care insurance, and (II) the willingness to admit non-cancer patients under the assumption that hospitalization costs would be covered by the health care insurance to the same level as cancer patients. Respondents were asked to use a 6-point scale (1= very necessary, 2= necessary, 3= somewhat necessary, 4= somewhat unnecessary, 5= not necessary, 6= not very necessary) to answer necessity, and a 6-point scale (1= very willing, 2= willing, 3= somewhat willing, 4= somewhat unwilling, 5= not willing, 6= not willing at all) to rate their willingness to accept the admission of non-cancer patients.

We asked about the support needs to admit the non-cancer patient to their facilities. Respondents were asked to use a 6-point scale (1= very necessary, 2= necessary, 3= somewhat necessary, 4= somewhat unnecessary, 5= not necessary, 6= not very necessary) to answer these questions (Appendix 1).

Statistical analysis

We conducted a descriptive analysis of the background characteristics of each facility, the necessity of health care insurance coverage of hospitalization costs of non-cancer patients, the willingness to accept the admission of non-cancer patients, and the support needs and conditions of non-cancer patients’ admission to their facilities.

As we aimed to explore the association between the willingness to accept admission and the support needs of non-cancer patients, which were ordinal variables, we divided this response into two categories: willingness to accept the admission of non-cancer patients (very willing to accept/willing to accept, and others), and the necessity of health coverage to admit non-cancer patients (very necessary/necessary, and others).

Subsequently, we investigated the association between the willingness and the support needs of non-cancer patients’ admission using the Spearman correlation coefficient. We included the number of responses to calculate the percentage of prevalence. Probability values were two-sided and statistical significance was P<0.05. All analyses were conducted using SPSS-J (ver. 28.0; IBM, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

A total of 264 facilities of 381 facilities responded to the survey (response rate: 69.3%), and we analyzed the answers of all 264 facilities. The mean number of beds of inpatient hospices/PCUs was 21.2±7.9. Moreover, 31.8% of facilities had 80.0% or more of their admissions referred from other hospitals, whereas 26.1% (n=69) of the facilities had less than 20.0% referrals. In addition, 15.2% (n=40) of the facilities had admitted non-cancer patients in the fiscal year 2020 (Table 1, Table S1). The most frequent conditions of non-cancer patients were chronic respiratory failure (n=34 patients, 12 facilities), chronic hepatic failure (n=33 patients, 6 facilities), and CHF (n=24 patients, 9 facilities). The number of patients that each facility accepts for admission is shown in Table S2.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of beds (means ± standard deviation) | |

| Hospital | 335.8±229.9 |

| PCUs | 21.2±7.9 |

| Admissions referred from other hospitals in 2020※, n (%) | |

| 100% | 13 (4.9) |

| 80% to less than 100% | 71 (26.9) |

| 60% to less than 80% | 42 (15.9) |

| 40% to less than 60% | 28 (10.6) |

| 20% to less than 40% | 32 (12.1) |

| Less than 20% | 61 (23.1) |

| None | 8 (3.0) |

| Admission of the non-cancer patients, n (%) | 40 (15.2) |

| Admission of the CHF patients, n (%) | 9 (3.4) |

| Admission of the chronic respiratory failure patients, n (%) | 12 (4.5) |

| Admission of the chronic hepatic failure patients, n (%) | 5 (1.9) |

| Admission of the CRF without dialysis patients, n (%) | 2 (0.8) |

| Admission of the chronic renal failure with dialysis patients, n (%) | 5 (1.9) |

| Admission of the intractable neurological disease patients, n (%) | 3 (1.1) |

| Admission of the dementia patients, n (%) | 3 (1.1) |

※, missing responses from two facilities. PCUs, palliative care units; CHF, chronic heart failure; CRF, chronic renal failure.

Among the facilities, 39.4% responded that they were “very willing” or “willing” to admit non-cancer patients under the assumption that hospitalization costs would be covered by health care insurance to the same level as cancer patients; moreover, this increased to 59.1% when those that responded “somewhat willing” were included (Table 2). Furthermore, 75.0% of the facilities answered that health care insurance coverage of hospitalization costs of non-cancer patients to the same level as cancer patients was “very necessary” or “necessary” (Table 2).

Table 2

| Necessity and willingness | All facilities (n=264) | Facilities accepting non-cancer patients (n=40) | Facilities not accepting non-cancer patients (n=224) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Necessity of health care insurance coverage of hospitalization costs of non-cancer patients, n (%) | |||

| Necessary at all | 157 (59.5) | 20 (50.0) | 135 (60.3) |

| Necessary | 41 (15.5) | 8 (20.0) | 33 (14.7) |

| Necessary somewhat | 36 (13.6) | 7 (17.5) | 29 (12.9) |

| Not necessary somewhat | 10 (3.8) | 1 (2.5) | 9 (4.0) |

| Not necessary | 12 (4.5) | 3 (7.5) | 9 (4.0) |

| Not necessary at all | 5 (1.9) | 1 (2.5) | 4 (1.8) |

| Missing value | 3 (1.1) | 0 | 5 (2.2) |

| Willingness to accept admission of non-cancer patients under the assumption that hospitalization costs covered by health care insurance, n (%) | |||

| Very willing | 34 (12.9) | 9 (22.5) | 24 (10.7) |

| Willing | 70 (26.5) | 12 (30.0) | 57 (25.4) |

| Willing somewhat | 52 (19.7) | 8 (20.0) | 43 (19.2) |

| Not willing somewhat | 62 (23.5) | 5 (12.5) | 57 (25.4) |

| Not willing | 30 (11.4) | 2 (5.0) | 28 (12.5) |

| Not willing at all | 11 (4.2) | 2 (5.0) | 9 (4.0) |

| Missing value | 5 (1.9) | 2 (5.0) | 6 (2.7) |

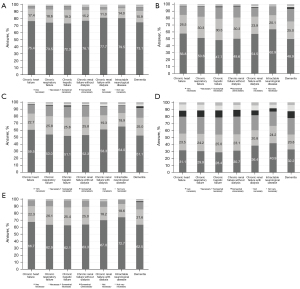

Figure 1 shows the support needs and the conditions to admit non-cancer patients. More than three-quarters of the facilities answered that “clarification of admission criteria”, “education and training system”, “advice from experts in the hospital”, and “guidelines and guidance are available” were “very necessary” or “necessary” for accepting the admission of patients for the purpose of palliative care who do not have a malignant tumor or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). On the other hand, about half of the facilities answered that “advice from experts outside the hospital” was “very necessary” or “necessary”.

Table 3 shows the association between the willingness to admit and the necessity of support and conditions to admit non-cancer patients to their facilities. A need for clarification of admission criteria for CHF (rs =−0.166, P=0.008), chronic respiratory failure (rs =−0.146, P=0.019), chronic hepatic failure (rs =−0.161, P=0.010), and CRF with dialysis (rs =−0.151, P=0.017) as well as the need for an education and training system for chronic respiratory failure (rs =−0.132, P=0.034) and advice from experts in the hospital for chronic respiratory failure (rs =−0.156, P=0.013) were significantly negatively associated with willingness to accept the admission of non-cancer patients to their facilities.

Table 3

| Necessity of support and conditions | Very willing/willing to admit non-cancer patients | |

|---|---|---|

| rs | P | |

| Clarification of admission criteria is very necessary/necessary | ||

| CHF | −0.166 | 0.008 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | −0.146 | 0.019 |

| Chronic hepatic failure | −0.161 | 0.010 |

| CRF without dialysis | −0.116 | 0.064 |

| CRF with dialysis | −0.151 | 0.017 |

| Intractable neurological disease | −0.062 | 0.321 |

| Dementia | −0.072 | 0.253 |

| Education and training systems are very necessary/necessary | ||

| CHF | −0.114 | 0.068 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | −0.132 | 0.034 |

| Chronic hepatic failure | −0.100 | 0.109 |

| CRF without dialysis | −0.104 | 0.095 |

| CRF with dialysis | −0.105 | 0.099 |

| Intractable neurological disease | −0.094 | 0.133 |

| Dementia | −0.080 | 0.205 |

| Advice from experts in the hospital is very necessary/necessary | ||

| Chronic heart failure | −0.105 | 0.095 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | −0.156 | 0.013 |

| Chronic hepatic failure | −0.093 | 0.140 |

| CRF without dialysis | −0.118 | 0.059 |

| CRF with dialysis | −0.107 | 0.091 |

| Intractable neurological disease | −0.037 | 0.556 |

| Dementia | −0.059 | 0.347 |

| Advice from experts outside the hospital is very necessary/necessary | ||

| Chronic heart failure | 0.034 | 0.589 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | −0.023 | 0.709 |

| Chronic hepatic failure | −0.023 | 0.715 |

| CRF without dialysis | 0.002 | 0.969 |

| CRF with dialysis | −0.011 | 0.859 |

| Intractable neurological disease | −0.026 | 0.685 |

| Dementia | −0.062 | 0.324 |

| Available guidelines and guidance are very necessary/necessary | ||

| Chronic heart failure | −0.091 | 0.144 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | −0.080 | 0.198 |

| Chronic hepatic failure | −0.037 | 0.559 |

| CRF without dialysis | −0.058 | 0.355 |

| CRF with dialysis | −0.047 | 0.463 |

| Intractable neurological disease | −0.027 | 0.669 |

| Dementia | −0.057 | 0.361 |

CHF, chronic heart failure; CRF, chronic renal failure.

Discussion

This cross-sectional nationwide survey was the first large survey to explore the current situation of non-cancer patients’ admission to inpatient hospices/PCUs, and the willingness and the support needed to accept the admission of non-cancer patients to inpatient hospices/PCUs in Japan.

The first important finding was that 15.2% of inpatient hospices/PCUs had accepted the admission of non-cancer patients, even though, unlike cancer patients, hospitalization costs are not covered by health care insurance in Japan. A previous cross-national retrospective study in Europe indicated that 65% of cancer patients received specialist palliative care, but only 36% of non-cancer patients (14). Another population survey in Australia indicated that the provision of specialist palliative care was significantly lower for non-cancer patients (40% versus 62%; P<0.001) (15).

Thus, our data suggests that non-cancer patients in Japan are less likely to be admitted to inpatient hospices/PCUs compared to Europe and Australia. However, future cross-national studies with unified measurement items and methods are needed.

Our data could also be used as a benchmark for other countries where specialist palliative care is focused on cancer patients. Assessing these data over time in each country could help to improve the provision of palliative care beyond cancer. In addition, qualitative research about the reasons why each facility accepted or did not accept the admission of non-cancer patients could clarify the key barriers to improving the provision of palliative care beyond cancer.

The second important finding was that a total of 59.1% of the facilities were willing to accept the admission of non-cancer patients to their facilities under the assumption that hospitalization costs covered by the health care insurance system would be to the same level as cancer patients. While 75.0% of facilities responded that health care insurance coverage of the hospitalization costs of non-cancer patients was very necessary or necessary, only 40.9% of the facilities were willing to accept the admission of non-cancer patients even if costs were covered by insurance. One possible interpretation is that the numerous support needs of facilities for the admission of non-cancer patients that were revealed in our study would be the further barriers beyond the lack of health insurance coverage. Thus, it is necessary to clarify the detailed reasons why facilities remained unwilling to accept non-cancer patients even if costs were covered by insurance.

The third important finding was that the necessity of clarification of admission criteria for several non-cancer diseases was significantly negatively associated with the willingness to accept the admission of non-cancer patients to inpatient hospices/PCUs. This finding may be due to the difficulty of predicting the prognosis of non-cancer patients (16). Thus, a practical solution may be to consider using the patient’s symptoms and level of distress as admission criteria for non-cancer patients to inpatient hospices/PCUs instead of their prognosis. Possible admission criteria based on the symptom/distress could be derived from the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicator Tool (SPICTTM) which is to identify patients at risk of deteriorating and dying in all care setting (17). The SPICT consists of several clinical indicators (e.g., persistent symptoms despite optimal treatment of the underlying condition, weight loss, or poor performance status) (17).

We found that the education and training system of palliative care for chronic respiratory failure was associated with willingness to accept the admission of non-cancer patients to inpatient hospices/PCUs. This result suggests that systematic nationwide education programs of palliative care, such as the Palliative Care Emphasis program on symptom management and Assessment for Continuous medical Education, for non-cancer patients may accelerate the provision of high-quality palliative care for non-cancer patients and their families (18,19). As well as an education program, a palliative care consultation system in the community, such as the Canadian Virtual Hospice (20), could be an important and practical solution to meet the needs of advice from experts.

This study had several limitations. First, the response rate of 69.3% was not enough to represent the current situation and opinions of all inpatient hospices/PCUs; however, we believe this response rate was acceptable to resolve our study question. Second, due to a lack of validated instruments, we used an original questionnaire that was developed based on a literature review, public health model, specialist discussion, and face validity testing. A quantitative study of patients, family members, and healthcare providers in inpatient hospices/PCUs will complement our understanding of why non-cancer patients are less frequently admitted to palliative care. Third, we lacked information about non-respondents. As this information could deepen the insight derived from the research, we would like to collect this information in a future survey.

Conclusions

Our study indicated that non-cancer patients’ admission to inpatient hospice/PCUs was not standard in Japan due to a lack of health care insurance coverage, clarity on admission criteria, and education on the palliative care of non-cancer patients. Therefore, we propose the establishment of a health insurance system in which appropriate palliative care is available regardless of disease, clarification of the admission criteria, and establishment of a systematic education program.

Acknowledgments

The authors express sincere thanks to Hospice Palliative Care Japan for supporting our study. The authors would like to thank Dr. Hirofumi Abo, Dr. Masayuki Ikenaga, Dr. Tatsuhiko Ishihara, Prof. Mitsunori Miyashita, Dr. Hiroyuki Otani, Dr. Kengo Imai, Dr. Keita Tagami, Ms. Megumi Kishino, Ms. Tomoko Shigeno, and Ms. Naoko Iwata for modifying or adding questions to the draft questionnaire. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Keiko Tanaka, Dr. Akihiro Tokoro, Dr. Seiji Adachi, Dr. Naoko Satou, Dr. Takae Niguma, Dr. Akemi Naitou, Dr. Takayuki Hisanaga, Prof. Takashi Yamaguchi, Dr. Hideyuki Kashiwagi, and Dr. Yusuke Hiratsuka for assessing the face validity of the draft questionnaires.

Funding: This study was supported in part by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant Nos. 19H03866 and 22H03305). The sponsor played no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-743/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-743/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-743/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The Institutional Review Board of the University of Tsukuba (No. 1691) approved the protocol of this study. The return of the completed questionnaire was regarded as consent to participate in the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- World Health Organization. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into primary health care. 2018.

- Lin LS, Huang LH, Chang YC, et al. Trend analysis of palliative care consultation service for terminally ill non-cancer patients in Taiwan: a 9-year observational study. BMC Palliat Care 2021;20:181. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hess S, Stiel S, Hofmann S, et al. Trends in specialized palliative care for non-cancer patients in Germany--data from the national hospice and palliative care evaluation (HOPE). Eur J Intern Med 2014;25:187-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ostgathe C, Alt-Epping B, Golla H, et al. Non-cancer patients in specialized palliative care in Germany: what are the problems? Palliat Med 2011;25:148-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance, The World Health Organization. WHO Global Atlas on Palliative Care. 2nd edition. 2020. Available online: http://www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care

- Van Lancker A, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S, et al. A comparison of symptoms in older hospitalised cancer and non-cancer patients in need of palliative care: a secondary analysis of two cross-sectional studies. BMC Geriatr 2018;18:40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bandeali S, des Ordons AR, Sinnarajah A. Comparing the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients with non-cancer and cancer diagnoses in a tertiary palliative care setting. Palliat Support Care 2020;18:513-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bajwah S, Oluyase AO, Yi D, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of hospital-based specialist palliative care for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;9:CD012780. [PubMed]

- Lin HM, Liu CK, Huang YC, et al. Exploratory Study of Palliative Care Utilization and Medical Expense for Inpatients at the End-of-Life. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:4263. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morita T, Kizawa Y. Palliative care in Japan: a review focusing on care delivery system. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2013;7:207-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kizawa Y, Yamaguchi T, Yagi Y, et al. Conditions, possibility and priority for admission into inpatient hospice/palliative care units in Japan: a nationwide survey. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2021;51:1437-43. [PubMed]

- Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD. The public health strategy for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:486-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD. Integrating palliative care into national policies. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:514-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pivodic L, Pardon K, Van den Block L, et al. Palliative care service use in four European countries: a cross-national retrospective study via representative networks of general practitioners. PLoS One 2013;8:e84440. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Currow DC, Agar M, Sanderson C, et al. Populations who die without specialist palliative care: does lower uptake equate with unmet need? Palliat Med 2008;22:43-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Osaka I, Sakashita A, Kizawa Y, et al. The Current Status of Palliative Care for Non-cancer Patients in Japan: Field Survey on the Representatives of the Japanese Society for Palliative Medicine. Palliative Care Research 2018;13:31-7. [Crossref]

- Highet G, Crawford D, Murray SA, et al. Development and evaluation of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT): a mixed-methods study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:285-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa Y, Yamamoto R, Kato M, et al. Improved knowledge of and difficulties in palliative care among physicians during 2008 and 2015 in Japan: Association with a nationwide palliative care education program. Cancer 2018;124:626-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto R, Kizawa Y, Nakazawa Y, et al. Outcome evaluation of the Palliative care Emphasis program on symptom management and Assessment for Continuous Medical Education: nationwide physician education project for primary palliative care in Japan. J Palliat Med 2015;18:45-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Stern A. The Canadian Virtual Hospice . J Palliat Care 2004;20:5-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]