Quality indicators for palliative care in intensive care units: a systematic review

Highlight box

Key findings

• 109 indicators were identified from 5 studies, and all 8 domains of the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care were covered.

• Indicators pertaining to the ethical and legal aspects of care were the most common, highlighting the importance of support for ICU staff.

What is known, and what is new?

• The integration of palliative care in ICUs in recent years has increased the importance of identifying relevant QIs and evaluating current practices.

• This systematic review provides an updated summary of the existing palliative care QIs in ICUs.

What is the implication, and what should change?

• This article provides current information on an aspect that would improve palliative care provided to critically ill patients and also bears implications for health care providers in palliative medicine.

• The findings pave the way for developing more appropriate quality indicators in palliative care, especially in the context of ICUs.

Introduction

In intensive care units (ICUs), many critically ill patients and their families require palliative care to improve their quality of life and provide relief from distress (1,2). Such care can be provided simultaneously with critical or therapeutic care (3). Approximately 20–70% of critically ill patients in ICUs experience pain, dyspnea, thirst, anxiety, depression, and other distressing issues; their physical and cognitive functions decline, causing emotional distress post discharge (4-7). Their families (4–94%) also experience psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (8,9). Thus, it is crucial to maintain high-quality palliative care for such patients and their families in ICUs (10-14).

To maintain and improve the quality of care, it must be measured (15); quality indicators (QIs) are critical for taking measurements (16). QIs can indicate good quality care (e.g., the proportion of patients whose pain assessment is well documented within the first day of hospitalization) and aspects that need improvement. Several studies have developed QIs of palliative care in the context of critical care (17-19). Additionally, some reviews of palliative care QIs in critical care settings, including cardiac ICUs (20), as well as in cases of cardiovascular diseases (21) and surgical patients (22), have clarified aspects requiring evaluation. Intensive care has developed rapidly worldwide over the last few decades, providing life-sustaining treatment and other advanced medical care to critically ill patients (23-25). Since ICUs cater to various serious illnesses, studying the QIs of ICU-specific palliative care is necessary. However, no systematic review has focused on this issue so far. The integration of palliative care in ICUs in recent years has increased the importance of identifying the relevant QIs and evaluating current practices.

This systematic review aims to provide an updated summary of the existing palliative care QIs in ICUs. It organizes the current aspects of palliative care quality assessment in ICUs to enable their further development. Specifically, it explores the coverage of the eight domains of quality palliative care listed in the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP), which contains practice guidelines for palliative care (26). The methodological quality of QI development was assessed based on the appraisal of indicators through a research and evaluation (AIRE) tool (27,28). We present this article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1005/rc).

Methods

Our systematic review procedure was designed according to PRISMA guidelines and registered with PROSPERO in December 2021 (Registration: CRD42021291436).

Data sources and search strategy

We performed a literature search in December 2021 through the MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane databases, along with the Ichushi-web database for Japanese literature. The search strategy was based on previous systematic reviews of palliative care QIs and a systematic review of ICU care (22,29-31). The search terms are presented in Appendix 1. The literature search was supplemented by a secondary manual search of citations of relevant studies. All studies published before November 2021 were included in the search. There were no language restrictions.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

All studies that presented the development process or characteristics of palliative care QIs in ICUs that explicitly stated the numerator and denominator of the palliative care QIs or enabled inference of this information from descriptions or that focused on QIs for the care of adult patients (18 years or older) were included in this systematic review.

The review excluded studies that only reported measures related to treatment or clinical care and did not include a palliative care component, studies that measured and reported performance and adherence as outcomes of an intervention, and other publications that were not original studies.

Study selection and data extraction

The study selection was conducted in two phases. First, two authors (Y.T. and K.M.) independently screened titles and abstracts. Second, they independently screened the full texts of these studies. A third author (M.M.) reviewed any disagreements over study inclusion until a consensus was reached. Rayyan, a software tool useful in supporting the screening for systematic reviews in healthcare research, was used for study selection (32,33).

For the selected studies, we summarized the country of origin, developmental design, data sources measured, and the Donabedian model of healthcare QI type (e.g., structure, process, and outcome) (34). Care structure refers to the ability of healthcare providers to fulfill patients’ needs with available physical and human resources. Care signifies an action performed in response to patients’ needs. Outcomes are the observed results or changes in the patient’s status due to the healthcare provider’s actions.

Three authors (Y.T., K.M., and M.M.) categorized each extracted indicator into eight palliative care domains, as defined by the NCP (Table 1) (26). If an indicator was relevant to multiple domains, we assigned its relevance to each category. The NCP domains are as follows: (I) Structure and Process of Care; (II) Physical Aspects of Care, (III) Psychological and Psychiatric Aspects of Care; (IV) Social Aspects of Care; (V) Spiritual, Religious, and Existential Aspects of Care; (VI) Cultural Aspects of Care; (VII) Care of the Imminently Dying Patient; (VIII) Ethical and Legal Aspects of Care.

Table 1

| Palliative care domains | Examples | N (% of total indicators)* |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Structure and Process of Care | Organizing training and education for professionals; providing continuity of care | 24 (19%) |

| 2. Physical Aspects of Care | Measuring and documenting pain and other symptoms; assessing and managing symptoms and side effects | 24 (19%) |

| 3. Psychological Aspects of Care | Measuring, documenting, and managing anxiety, depression, and other psychological symptoms; assessing and managing the psychological reactions of patients/families | 8 (6%) |

| 4. Social Aspects of Care | Conducting regular patient/family care conferences to provide information, discuss goals of care, and offer support to patients or families; developing and implementing comprehensive social care plans | 6 (5%) |

| 5. Spiritual, Religious, and Existential Aspects of Care | Providing information about the availability of spiritual care services to patients or families | 9 (7%) |

| 6. Cultural Aspects of Care | Incorporating cultural assessments, such as the locus of decision-making and preferences of patients or families regarding the disclosure of information and truth-telling, language, and rituals | 3 (2%) |

| 7. Care of the Imminently Dying Patient | Recognizing and documenting the transition to the active dying phase; ascertaining and documenting patient/family wishes about the place of death; implementing a bereavement care plan | 16 (12%) |

| 8. Ethical and Legal Aspects of Care | Documenting patient/surrogate preferences for care goals, treatment options, and the care setting; making advance directives; promoting advance care planning | 38 (30%) |

*, nineteen indicators covered multiple domains: fifteen indicators fell under two domains and four under three domains.

Critical appraisal of methodological quality

We used the AIRE tool to evaluate the methodological quality of the QI determination process across the sets of indicators. Prior systematic reviews of QIs (22,29,30) use the same method. The AIRE tool has 20 items across the four domains: purpose, relevance, and organizational context; stakeholder involvement; scientific evidence; and additional evidence, formulation, and usage. The tool uses a four-point Likert scale (1= strongly disagree, 2= disagree, 3= agree, 4= strongly agree) to score each item based on whether it meets the criteria. Four authors (Y.T., K.M., A.K., and H.H.) independently evaluated the data according to the recommendations of the original AIRE tool, which was prepared in Dutch.

We used the English translation of the AIRE tool available from the developer (Amsterdam UMC). The sum of the scores in each category was standardized as a percentage from 0% to 100% based on the category’s maximum score, with higher percentages indicating higher methodological quality. Any additional information in the indicator development needed to complete the AIRE tool-based assessment was supplemented with external references. We summarized all QIs related to palliative care for ICU patients. Therefore, no QIs were excluded due to methodological quality.

Results

Search results

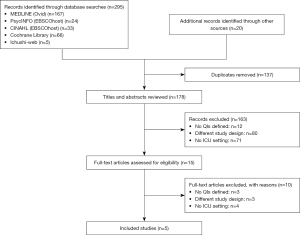

A total of 295 studies were identified during the initial search, and the manual search identified an additional 20 (Figure 1). After excluding duplicates, 178 titles and abstracts were reviewed; of these, 163 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. A full-text screening of 15 studies was performed, and 5 matched the inclusion criteria. Finally, 5 studies published between 2003 and 2019 were included, and 109 indicators were extracted.

Overview of the QI sets

Table 2 shows the included studies and their characteristics (17-19,35,36). In most of these studies, a formal consensus process was used to develop indicators, and stakeholder consensus was obtained.

Table 2

| Studies | Author, year (country) | Development methodology | Data source to measure | Structure (%) | Process (%) | Outcome (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Clarke et al., 2003 (USA) (17) | Literature review, expert consensus | No specific description | 9 | 44 | 0 | 53 |

| B | Nelson et al., 2006 (USA) (18) | Literature review, expert consensus, pilot study | Medical records, Review of ICU policies and protocol | 1 | 9 | 0 | 10 |

| C | Mularski et al., 2006 (USA) (19) | Literature review, expert consensus | Medical records, Review of ICU policies and protocol | 4 | 14 | 0 | 18 |

| D | Mularski et al., 2016 (USA) (35) | RAND/UCLA method: Literature review, expert panel | Medical records | 0 | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| E | Kruser et al., 2019 (USA) (36) | Literature review | Registry database, REDCap | 5 | 4 | 5 | 14 |

| Total | 19 (17%) | 85 (78%) | 5 (5%) | 109 |

ICU, intensive care unit; REDCap, Research Electronic Data Capture.

Patients and families were the target audience for many indicators, but some were related to healthcare team support. All five studies were conducted in the United States. The seven domains of “quality measures in palliative and end-of-life care” presented by Clarke et al. (17) were referenced in every study.

Based on the Donabedian model of quality categories, process indicators were the most common, accounting for 78% (n=85) of the total. For example, some process indicators focus on the provision and documentation of care, such as the record of desire for life-maintaining treatment and assessment and management of pain and dyspnea. Structural indicators accounted for 17% (n=19) of the total. They included protocols to standardize palliative care, free family visits, leaflets to provide information to families, and support available for health care providers. Outcome measures were presented in only one study (5%, n=5). These included lack of pain in the day of life, no CPR in the last hour of life, and the presence of family members at the moment of death. Most data on QI measures and data sources were derived from a review of electronic medical records (EMRs).

QIs by the domains of palliative care

Tables 1,3 show the results of the categories pertaining to palliative care listed in the NCP. The identified indicators covered all eight palliative care domains of the NCP. A total of 19 indicators addressed multiple domains; of these, 15 covered 2 domains, and 4 covered 3 domains. Since the contents of each indicator overlapped, every indicator was integrated, and sub-domains of palliative care in ICUs were established.

Table 3

| Donabedian model (n, %) | Indicators: sub-domains of palliative care in ICUs | Measurement: Numerator/Denominator | Data sources | NCP domains** | Studies covered* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | |||||

| Structure (n=19, 17%) | Support for ICU staff | ||||||||

| A policy that supports a regular, structured opportunity for staff to reflect on the experience of caring for dying patients | Numerator: Presence of a forum for ICU clinicians to review, discuss, and debrief the experience of caring for dying patients and their families. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Facilitate rituals for the staff to mark the death of patients | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1 | √ | |||||

| Enlist palliative care experts, pastoral care representatives, and other consultants to teach and model aspects of end-of-life care | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1 | √ | |||||

| Communicate regularly with an interdisciplinary team regarding goals of care | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1 | √ | |||||

| Adjust nursing staff and medical rotation schedules to maximize continuity of care providers for dying patients | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1 | √ | |||||

| Open visitation policy and meeting room for family members | |||||||||

| Open visitation policy for family members | Numerator: The presence of a policy in the ICU that allows for family members and friends to spend time in the patient’s room, regardless of the time of day. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1 | √ | √ | ||||

| Family meeting room: Dedicated meeting space between clinicians and ICU families | Numerator: Family meeting room: dedicated space for meetings between clinicians and families. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1, 8 | √ | √ | ||||

| Providing information on ICUs and continuity of care | |||||||||

| Policy for continuity of nursing services | Numerator: The presence of an ICU policy that supports arranging nursing continuity for patients who stay multiple days in the ICU. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Symptom management and comfort care | |||||||||

| Emphasize the comprehensive comfort care that will be provided to the patient rather than the removal of life-sustaining treatments | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1, 2 | √ | |||||

| Institute and use uniform quantitative symptom assessment scales appropriate for communicative and non-communicative patients on a routine basis | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1, 2 | √ | |||||

| Standardize and follow best clinical practices for symptom management | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility policies | 1, 2 | √ | |||||

| EOL ICU care | |||||||||

| EOL-specific protocols for general symptom management | Numerator: Presence of protocols for general symptom management. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility protocols | 1, 2, 7 | √ | |||||

| Protocol for analgesia/sedation in terminal withdrawal of mechanical ventilation | Numerator: Presence of a protocol that can be applied in settings of terminal withdrawal of mechanical ventilation. Denominator: ICU | Review of facility protocols | 1, 2, 7 | √ | √ | ||||

| Process (n=85, 78%) | Providing information on ICUs and continuity of care | ||||||||

| Transmission of key information with the transfer of the patient out of the ICU | Numerator: Total number of patients transferred out of the ICU with documentation showing that the goals of care and resuscitation status were communicated to the receiving team. Denominator: Total number of patients transferred from the ICU alive to another service in the hospital or other care facility | Review of individual medical records | 1 | √ | √ | ||||

| Family information leaflet that includes orientation to the ICU environment and an open visitation policy for family members | Numerator: Total number of patients whose families received information leaflets from ICU team members. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h | Review of individual medical records, Review of facility policies | 1 | √ | √ | ||||

| Symptom management and comfort care | |||||||||

| Documentation of pain assessment | a) Numerator: Total number of 4-h periods during the portion of the 24-h day that a patient is in the ICU or under the care of the ICU nurse for which pain is assessed and recorded using a quantitative rating scale; b) Numerator: Documentation of pain over the last 48 h; c) Numerator: Documentation of pain over the first 48 h. Denominator: Total number of 4-h periods during the portion of the 24-h day that the patient is in the ICU or under the care of the ICU nurse | Review of individual medical records | 2 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| A | B | C | D | E | |||||

| Documentation of pain management | Numerator: Total number of 4-h periods during the portion of the 24-h day that a patient is in the ICU or under the care of the ICU nurse for which pain is assessed as 3 (or greater than mild), and there is documentation of treatment provided and of reassessment within 2 h after treatment. Denominator: Total number of 4-h periods during the portion of the 24-h day that a patient is in the ICU or under the care of the ICU nurse for which pain is assessed as 3 (or greater than mild) | Review of individual medical records | 2 | √ | √ | ||||

| Documentation of respiratory distress assessment | a) Numerator: Total number of 8-h periods during the portion of the 24-h day that a patient is in the ICU or under the care of the ICU nurse for which dyspnea/dyssynchrony is assessed and recorded using a quantitative rating scale; b) Numerator: Documentation of dyspnea over the last 48 h; c) Numerator: Documentation of dyspnea over the first 48 h. Denominator: Total number of 8-h periods during the portion of the 24-h day that the patient is in the ICU or under the care of the ICU nurse | Review of individual medical records | 2 | √ | √ | ||||

| Process (n=85, 78%) | Documentation of respiratory distress management | Numerator: Total number of 8-h periods during the portion of the 24-h day that a patient is in the ICU or under the care of the ICU nurse for which respiratory distress/dyssynchrony is assessed as 3 (or greater than mild), and there is documentation of treatment/management plan provided and of reassessment within 2 h after treatment/management plan. Denominator: Total number of 8-h periods during the portion of the 24-h day that a patient is in the ICU or under the care of the ICU nurse for which respiratory distress/dyssynchrony is assessed as 3 (or greater than mild) | Review of individual medical records | 2 | √ | ||||

| Use non-pharmacologic as well as pharmacologic measures to maximize comfort as appropriate and desired by the patient and family | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Review of individual medical records | 2 | √ | |||||

| Reassess and document symptoms following interventions | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Review of individual medical records | 2 | √ | |||||

| Minimize noxious stimuli (monitors, strong lights) | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 2 | √ | |||||

| Attend to patient’s appearance and hygiene | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 2 | √ | |||||

| Process (n=85, 78%) | Psychological and practical support for patients and families | ||||||||

| Documentation showing that psychosocial support has been offered | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h with psychosocial support offered to the patient or family by any team member. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h | Review of individual medical records | 3, 4 | √ | √ | ||||

| Elicit and attend to the dying person’s needs and their family | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 3 | √ | |||||

| Facilitate strengthening of patient-family relationships and communication | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 3 | √ | |||||

| Social work support for patients and families | |||||||||

| Documentation showing that social-work support was offered to the patient/family | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h with documentation showing that social-work support was offered to the patient/family. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h | Review of individual medical records | 4 | √ | |||||

| Arrange for social support for patients without family or friends | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Review of individual medical records | 4 | √ | |||||

| Distribute written material (booklet) containing essential logistical information and listings of financial consultation services and bereavement support programs/resources | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Review of individual medical records | 4 | √ | |||||

| Spiritual support for patients and families | |||||||||

| Documentation showing that spiritual support was offered | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h with an offering of spiritual support by any team member. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h and with family members visiting | Review of individual medical records | 5 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Process (n=85, 78%) | Encourage access to spiritual resources | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 5 | √ | ||||

| Elicit and facilitate spiritual and cultural practices that the patient and family find comforting | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 5, 6 | √ | |||||

| A | B | C | D | E | |||||

| Utilize expert clinical, ethical, and spiritual consultants when appropriate | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Review of individual medical records | 5 | √ | |||||

| Recognize the adaptations in communication strategy required for patients and families according to the chronic vs. acute nature of illness, cultural and spiritual differences, and other influences | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | 5, 6 | √ | ||||||

| Value and support the patient’s and family’s cultural traditions | |||||||||

| Value and support the patient’s and family’s cultural traditions | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 6 | √ | |||||

| End-of-life ICU care | |||||||||

| Appropriate medications are available during withdrawal of mechanical ventilation | Numerator: Total number of non-comatose patients for whom mechanical ventilation is withdrawn in anticipation of death who have orders written for opiates or benzodiazepines as scheduled or as needed. Denominator: Total number of non-comatose patients for whom mechanical ventilation is withdrawn in anticipation of death | Review of individual medical records | 2, 7 | √ | √ | ||||

| At least 1 pain assessment is documented in the EHR in the last 24 hours of life | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h with documentation showing at least 1 pain assessment. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h | Review of individual medical records | 2, 7 | √ | |||||

| At least 1 delirium assessment was documented in the EHR in the last 24 hours of life | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h with documentation showing at least 1 delirium assessment. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h | Review of individual medical records | 3, 7 | √ | |||||

| Prepare the patient and family for the dying process | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 3, 7 | √ | |||||

| Process (n=85, 78%) | Know and follow best clinical practices for withdrawing life-sustaining treatments to avoid patient and family distress | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 2, 3, 7 | √ | ||||

| Eliminate unnecessary tests and procedures (laboratory work, weights, routine vital signs) and only maintain intravenous catheters for symptom management in situations where life-support is withdrawn | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Review of individual medical records, Administrative database | 7 | √ | |||||

| Care to the family after a bereavement | |||||||||

| Support the family through the patient’s death and bereavement | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: ICU patients’ family | Review of individual medical records | 7 | √ | |||||

| Patient and family-centered decision making | |||||||||

| Assessment of the decisional capacity of the patient | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU with documentation of decisional capacity made within 24 h of admission. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h | Review of individual medical records | 8 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Documentation showing the surrogate decision maker(s) within 24 h of admission | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h with documentation showing the surrogate decision maker(s) or documentation regarding the absence of any surrogate decision maker(s). Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h | Review of individual medical records | 8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Documentation showing the presence and, when so, the contents of advance directives | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h with documentation showing the presence or absence of an advance directive (including a living will or durable power of attorney for health care) and, when so, documentation showing the contents of the advance directive or a copy of the advance directive in the patient chart. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h | Review of individual medical records | 8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Documentation of the goals of care | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h with documentation of the goals of care. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h | Review of individual medical records | 8 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Documentation of resuscitation status | Numerator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h with documentation of the resuscitation status. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h | Review of individual medical records | 8 | √ | √ | ||||

| Recognize the patient and family as the unit of care | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Assess the patient’s and family’s decision-making style and preferences | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| A | B | C | D | E | |||||

| Process (n=85, 78%) | Address conflicts in decision-making within the family | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | ||||

| Initiate advance care planning with the patient and family | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A. | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Assure patients and families that decision-making by the healthcare team will incorporate their preferences | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Follow ethical and legal guidelines for patients who lack both capacity and a surrogate decision-maker | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Help the patient and family assess the benefits and burdens of alternative treatment choices as the patient’s condition changes | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Forego life-sustaining treatments in a way that ensures patient and family preferences are elicited and respected | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Communication within the ICU team and with patients and families | |||||||||

| Documentation showing timely physician communication with the family | Numerator: Patients in the ICU for 24 h for whom there is documentation showing that a physician communicated with a family member or friend of the patient in person or by phone. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 24 h for whom a family member or friend can be identified | Review of individual medical records | 8 | √ | √ | ||||

| Documentation showing a timely interdisciplinary clinician–family conference | Numerator: Patients in the ICU for 72 h for whom there is documentation showing that an interdisciplinary clinician-family conference took place that included at least one family member or friend of the patient, a physician, and another clinician (other than a physician) and for which the documentation includes a description of what was discussed. Denominator: Total number of patients in the ICU for 72 h for whom a family member or friend can be identified | Review of individual medical records | 8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Address conflicts among the clinical team before meeting with the patient and/or family | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Meet with the patient and/or family regularly to review the patient’s status and answer questions | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Communicate all information to the patient and family, including distressing news, in a clear, sensitive, unhurried manner and an appropriate setting | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Clarify the patient’s and family’s understanding of the patient’s condition and care goals at the beginning and end of each meeting | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Designate primary clinical liaison(s) who will communicate with the family daily | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Identify a family member who will serve as the contact person for the family | Numerator: N/A. Denominator: N/A | Not specified | 8 | √ | |||||

| Outcome (n=5, 5%) | End-of-life ICU care | ||||||||

| Extubation or discontinuation of invasive mechanical ventilation before the time of death among patients receiving mechanical ventilation | Numerator: Total number of extubations or discontinuations of invasive mechanical ventilation before the time of death among patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Denominator: Total number of patients who died that received mechanical ventilation in the ICU for 24 h | Review of individual medical records, Registry database | 7 | √ | |||||

| Absence of CPR in the last hour of life | Numerator: Total number of patients who did not receive CPR in the last hour of life. Denominator: Total number of patients who died in the ICU | Review of individual medical records, Registry database | 7 | √ | |||||

| Being delirium-free in the last 24 hours of life | Numerator: Total number of delirium-free patients in the last 24 hours of life. Denominator: Total number of patients who died in the ICU | Review of individual medical records, Registry database | 3, 7 | √ | |||||

| Being pain-free in the last 24 hours of life | Numerator: Total number of pain-free patients in the last 24 hours of life. Denominator: Total number of patients who died in the ICU | Review of individual medical records, Registry database | 2, 7 | √ | |||||

| Presence of family members or other significant persons at the time of death | Numerator: Total number of patients with family members or other significant persons present at the time of death. Denominator: Total number of patients who died in the ICU | Review of individual medical records, Registry database | 7 | √ | |||||

*, studies, A: Clarke et al., 2003 (17). B: Nelson et al., 2006 (18). C: Mularski et al., 2006 (19). D: Mularski et al., 2016 (35). E: Kruser et al. 2019 (36). **, National Consensus Project (NCP) Domains are 1: Structure and Processes of Care; 2: Physical Aspects of Care; 3: Psychological and Psychiatric Aspects of Care; 4: Social Aspects of Care; 5: Spiritual, Religious, and Existential Aspects of Care; 6: Cultural Aspects of Care; 7: Care of the Patient Nearing the End of Life; 8: Ethical and Legal Aspects of Care. ICU, intensive care unit; NCP, National Consensus Project; EOL, end of life; EHR, electronic health record; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; N/A, not available.

The most frequent NCP domain pertained to ethical and legal aspects (n=38, 30%). It included the sub-domains “patient and family-centered decision making” and “communication within the ICU team and with patients and families”. This was followed by physical aspects (n=24, 19%), which included the sub-domain “symptom management and comfort care”, and structure and process of care (n=24, 19%), which included the sub-domain “support for ICU staff”. By contrast, cultural aspects (n=3, 2%) and social aspects (n=6, 5%) had fewer indicators.

Critical appraisal of methodological quality of indicator development

Table 4 presents the evaluation results of the methodological quality of indicator development. The indicators were estimated from descriptions, even when the numerator and denominator were not clearly described. QI set scores were reliably high-ranking (exceeding 70%) for all constructs regarding “purpose, relevance, and organizational content.” The “scientific evidence” used to develop the indicators varied between 11% to 89%. The stakeholders were mostly physicians and nurses; no patients or family members participated. Scores varied (24–77%) across the indicator set, “additional evidence, formulation, usage”, which indicates specific measures and actual applications.

Table 4

| Methodological Characteristics | Category 1: purpose, relevance, and organizational context, % | Category 2: stakeholder involvement, % | Category 3: scientific evidence, % | Category 4: additional evidence, formulation, usage, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarke EB et al. 2003 | 70 | 19 | 33 | 24 |

| Nelson JE et al. 2006 | 85 | 86 | 89 | 62 |

| Mularski RA et al. 2006 | 82 | 86 | 75 | 48 |

| Mularski RA et al. 2016 | 90 | 72 | 28 | 77 |

| Kruser JM et al. 2019 | 72 | 3 | 11 | 47 |

*, AIRE tool, Appraisal of indicators through research and evaluation tool.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 5 existing indicator sets for the quality assessment of palliative care in ICUs and extracted 109 indicators. These existing indicators cover all eight palliative care domains listed in the NCP, although the number of items varies by domain. As per the Donabedian classification, most indicators were process indicators (78%, n=85). Many of these were not specifics of care but were related to the presence or absence of assessment documentation. The most unique palliative care QI domain in ICUs was related to ethical and legal aspects, indicating the importance of “support for ICU staff”. There were few outcome indicators (5%, n=5). Additionally, only a few studies had a high level of scientific evidence regarding the methodological quality of indicator development.

This systematic review yielded several findings. First, the high proportion of process indicators (60–70%) in palliative care QIs is similar to that reported in previous studies (22,30). Although other QI studies emphasized the importance of documenting care (37-41), documentation alone may not adequately measure the quality of care. Thus, QIs that evaluate the care itself are needed, along with those that assess documentation. To develop QIs, it is necessary to define the desired care and to propose recommendations for palliative care in ICUs. In an ICU setting, it may be difficult to establish a specific denominator and present a standard or recommended treatment approach because of each patient’s various illnesses and trajectories. Clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements about pain management in critically ill, end-of-life patients propose a management algorithm to improve the overall care of such patients, but these have not been validated (42). Evidence for care other than for pain has not been well established. When the evidence for the care of distress symptoms is established in the future, it will be necessary to propose QIs consistent with the standard of care.

Second, ethical and legal aspects emerged in a high percentage as a unique attribute of palliative care QIs in ICUs; some indicators focused on supporting ICU staff. The domain of “ethical and legal aspects of care” included assessing decision-making capacity, determining surrogate decision-makers, and having discussions with the health care provider about the goals of care. Lack of decision-making ability is a major characteristic of patients admitted to the ICU, and the decision-making process and discussion about care goals are essential components of palliative care in ICUs (10,43,44). The lack of patients’ decision-making capacity is a distinctive issue related to decisions to discontinue or withhold advanced life-sustaining treatments, such as being put on a ventilator or receiving dialysis. Healthcare providers must balance various medical, ethical, and legal considerations (45-49). Inadequate communication about decision-making is associated with unwanted invasive treatments at the end of life, low family satisfaction with care, and an increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms and anxiety among family members (50-53). Thus, documentation of patient/proxy preferences regarding care objectives, treatment alternatives, and care environment, as well as instructions for and promotion of planning for care, can be indicators for supporting patient- and family-centered decision-making.

Support for ICU staff is a measure of structural aspects. It includes the availability of psychological support for ICU staff and the availability of consultation with a clinical ethics committee or palliative care expert. ICU staff who participate in end-of-life decision-making show a higher prevalence of burnout than providers in other departments (54,55). The availability of a consultation system for palliative care and a clinical ethics committee have been suggested as measures to reduce the burnout risk among ICU medical staff (54,56,57). In brief, managing the mental health of ICU staff is critical to continue providing quality care to ICU patients. Adequate training in palliative care for ICU staff is another important issue related to improving the quality of palliative care (58). Receiving training on palliative care is associated not only with the staff’s improved professional knowledge and skills but also with a reduction in their moral distress (59).

Third, a few outcome indicators (5%, n=5) were identified. Outcome indicators are essential components in the evaluation of the quality of care. While many process indicators can be evaluated without involving patients or their families, outcome indicators require asking patients about their attitudes and perceptions regarding the care they receive. A large cohort study of end-of-life patients in ICUs measured outcomes in the following categories: withholding life-prolonging treatment, discontinuing life-prolonging treatment, actively shortening time to death, failure of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and brain death (60). Although patient-reported outcomes (PRO) have gained importance as an outcome measure (61,62), ICU patients often cannot express their opinions. They have difficulty providing PRO data because of their reduced level of consciousness caused by illness or treatment. However, quality evaluation projects for palliative care, such as Measuring What Matters (MWM) (41) and the Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC) (63), have recommended and collected PRO data and family members’ assessment of the quality of care.

Outcome indicators must be established to assess the quality of palliative care in ICUs. Several measurement tools have been developed and used to assess palliative care in ICUs. For example, the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) questionnaire (53,64) evaluates the quality of care based on family satisfaction. The Quality of Death and Dying (QODD) questionnaire evaluates the quality of ICU palliative care provided to patients from the perspective of family members after the patient’s death (65-69). A survey of patients/families and bereaved families using such a scale may be required to understand the outcomes of palliative care in the future.

Fourth, studies with a high level of scientific evidence for the methodological quality of QI development are lacking. This may reflect the limited effectiveness of palliative care interventions in the ICUs that were not well established at the time of the QI development. In a previous review of surgical palliative care QIs (22), the range of scores for the scientific evidence category for 17 studies was 33–100%, with the same variability as the 5 studies in this review (range, 11–89%). Scores varied between 24–77% across the indicator set “additional evidence, formulation, usage”, indicating specific measures and actual applications. This reflects the paucity of studies that piloted the indicators and discussed their actual application. QIs with high AIRE scores might be appropriate for daily evaluations, while the other sets require further development and enhancement before consideration as QIs. Palliative care practices in ICUs and their effectiveness must be evaluated and evidence accumulated to develop important QIs that should be prioritized and continuously evaluated in the future.

Future research

Future studies need to establish methods for evaluating the QIs of palliative care in ICUs following the Donabedian model of quality. While this article summarized palliative care QIs according to the traditionally used Donabedian model, classifying and measuring palliative care using the new palliative care quality assessment framework proposed by Kamal et al. (70) may be useful for improving patient and system outcomes. Previous studies used appropriate methods for quality assessment, such as facility surveys (71), medical chart reviews (72,73), patient surveys (74), family (bereaved family) surveys (75-77), and administrative data surveys (78-81). Therefore, it is important to consider methods for collecting and evaluating QIs of palliative care in ICUs, as well as to establish a specific QI set.

The handling of EMRs is crucial for QIs of palliative care in ICUs, and methods for dealing with these data are being developed. As this review showed, QIs of palliative care in ICUs were mostly based on content that could be obtained from EMRs. As data from EMRs are routinely collected, they have the advantage of providing clinical information without imposing any burden on healthcare providers or patients regarding secondary uses, such as research or quality assessment. Thus, the retrospective measurement of the care process from EMRs using QIs is a traditional method for measuring the quality of care. Specifically, documentation about communication, such as decision-making and discussion of goals of care, is important in assessing the quality of care, and it is recorded as text data in EMRs (82,83). However, evaluating these data requires both time and money, rendering manual evaluation difficult. Natural language processing and machine learning techniques have recently demonstrated the ability to handle textual data from EMRs, putting a little burden on healthcare providers or patients in palliative care settings (84-86). Chan et al. demonstrated that automatic evaluation using a deep learning algorithm system could perform accurate automated text-based information classification of serious illness conversations in the context of ICU palliative care QIs (87). This state-of-the-art technology could enable rapid auditing and feedback on documentation at the systemic and individual practitioner levels. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate these techniques to continuously evaluate the quality of palliative care in ICUs.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review adhered to the PRISMA guidelines and the methodological quality of QI development was assessed using the AIRE tool. However, it has several limitations. First, we systematically searched international databases containing primarily peer-reviewed scientific literature. However, we could not search EMBASE at our institution because we did not have a database subscription. Nevertheless, a manual search including gray literature was performed, which was considered complementary. It also should be noted that some QIs may have been missed, as QIs for palliative care has not always been published (88). Second, since all the studies were conducted in the United States, the results are not generalizable to other countries. While guidelines for palliative care have been reviewed and published in many countries because of the need for consideration of ethical and legal aspects (89-91), uniform international quality standards for palliative care are generally lacking, and the development and measurement of QI have not been consistently reported. Quality palliative care is also important in low- and middle-income countries (92). Future development of an international and universally applicable QI is necessary. Third, although the methodological evaluation was based on information obtained from the literature, the indicator development process was not always described in detail. Consequently, the methodological quality of the indicator set described in this review could be underestimated because the AIRE tool focuses primarily on the development process.

Conclusions

The QIs of palliative care in ICUs and 109 indicators covered all 8 palliative care domains of the NCP. Most of these indicators were process indicators, whereas few were outcome indicators. Ethical and legal aspects of care emerged as a unique domain of ICU palliative care. Most indicators pertained to this domain, and the emphasis on support for ICU staff was evident. Although existing QIs can be used to implement palliative care in the ICU, more specific indicators are needed. In the future, implementing continuous quality assessment and improvement and adding more palliative care practices in ICUs could provide further evidence and help develop valid QIs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank everyone who contributed to the article.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1005/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1005/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1005/coif). Mitsunori Miyashita serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Palliative Medicine from February 2022 to January 2024. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2506-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization: Definition of Palliative Care [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 12]. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/palliative-care

- Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:912-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puntillo KA, Arai S, Cohen NH, et al. Symptoms experienced by intensive care unit patients at high risk of dying. Crit Care Med 2010;38:2155-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi J, Hoffman LA, Schulz R, et al. Self-reported physical symptoms in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors: pilot exploration over four months post-ICU discharge. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:257-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hashem MD, Nallagangula A, Nalamalapu S, et al. Patient outcomes after critical illness: a systematic review of qualitative studies following hospital discharge. Crit Care 2016;20:345. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, et al. Anxiety, Depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after critical illness: a UK-wide prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2018;22:310. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McAdam JL, Dracup KA, White DB, et al. Symptom experiences of family members of intensive care unit patients at high risk for dying. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1078-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson CC, Suchyta MR, Darowski ES, et al. Psychological Sequelae in Family Caregivers of Critically III Intensive Care Unit Patients. A Systematic Review. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019;16:894-909. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelson JE, Puntillo KA, Pronovost PJ, et al. In their own words: patients and families define high-quality palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2010;38:808-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelson JE, Azoulay E, Curtis JR, et al. Palliative care in the ICU. J Palliat Med 2012;15:168-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2014;42:2418-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mercadante S, Gregoretti C, Cortegiani A. Palliative care in intensive care units: why, where, what, who, when, how. BMC Anesthesiol 2018;18:106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aslakson RA, Cox CE, Baggs JG, et al. Palliative and End-of-Life Care: Prioritizing Compassion Within the ICU and Beyond. Crit Care Med 2021;49:1626-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Quality Forum. Measuring Performance [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 16]. Available online: https://www.qualityforum.org/Measuring_Performance/Measuring_Performance.aspx

- Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, et al. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ 2003;326:816-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, et al. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2003;31:2255-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelson JE, Mulkerin CM, Adams LL, et al. Improving comfort and communication in the ICU: a practical new tool for palliative care performance measurement and feedback. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:264-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, et al. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Crit Care Med 2006;34:S404-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takaoka Y, Hamatani Y, Shibata T, et al. Quality indicators of palliative care for cardiovascular intensive care. J Intensive Care 2022;10:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mizuno A, Miyashita M, Hayashi A, et al. Potential palliative care quality indicators in heart disease patients: A review of the literature. J Cardiol 2017;70:335-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee KC, Sokas CM, Streid J, et al. Quality Indicators in Surgical Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021;62:545-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Japanese Intensive Care Patient Database. jipad_report_2020.pdf [Internet]. Available online: https://www.jipad.org/images/include/report/report2020/jipad_report_2020.pdf

- Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre. Summary Statistics [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 16]. Available online: https://www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports/Summary-Statistics

- Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society. CORE Reports [Internet]. ANZICS. 2018 [cited 2022 May 16]. Available online: https://www.anzics.com.au/annual-reports/

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 4th edition. Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care, 2018. Available online: https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp

- De Koning J, Smulders A, Klazinga N. Appraisal of indicators through research and evaluation (AIRE). Academisch Medisch Centrum Universiteit van Amsterdam, afdeling Sociale Geneeskunde, Amsterdam; 2007.

- de Koning JS, Kallewaard M, Klazinga NS. Prestatie-indicatoren langs de meetlat – het AIRE instrument. Tijdschr Soc Gezondheidsz 2007;85:261-4. [Crossref]

- Pasman HR, Brandt HE, Deliens L, et al. Quality indicators for palliative care: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:145-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Roo ML, Leemans K, Claessen SJ, et al. Quality indicators for palliative care: update of a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:556-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rose L, Istanboulian L, Allum L, et al. Patient- and family-centered performance measures focused on actionable processes of care for persistent and chronic critical illness: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2017;6:84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rayyan – Intelligent Systematic Review [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 12]. Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/

- Harrison H, Griffin SJ, Kuhn I, et al. Software tools to support title and abstract screening for systematic reviews in healthcare: an evaluation. BMC Med Res Methodol 2020;20:7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988;260:1743-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mularski RA, Hansen L, Rosenkranz SJ, et al. Medical Record Quality Assessments of Palliative Care for Intensive Care Unit Patients. Do They Match the Perspectives of Nurses and Families? Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:690-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kruser JM, Aaby DA, Stevenson DG, et al. Assessment of Variability in End-of-Life Care Delivery in Intensive Care Units in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1917344. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lorenz KA, Dy SM, Naeim A, et al. Quality measures for supportive cancer care: the Cancer Quality-ASSIST Project. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37:943-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walling AM, Asch SM, Lorenz KA, et al. The quality of care provided to hospitalized patients at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1057-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walling AM, Tisnado D, Asch SM, et al. The quality of supportive cancer care in the veterans affairs health system and targets for improvement. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:2071-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walling AM, Ahluwalia SC, Wenger NS, et al. Palliative Care Quality Indicators for Patients with End-Stage Liver Disease Due to Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:84-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dy SM, Kiley KB, Ast K, et al. Measuring what matters: top-ranked quality indicators for hospice and palliative care from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:773-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Durán-Crane A, Laserna A, López-Olivo MA, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Consensus Statements About Pain Management in Critically Ill End-of-Life Patients: A Systematic Review. Crit Care Med 2019;47:1619-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levy MM. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: can we do better? Crit Care Med 2001;29: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelson JE, Mathews KS, Weissman DE, et al. Integration of palliative care in the context of rapid response: a report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU advisory board. Chest 2015;147:560-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jensen HI, Ammentorp J, Johannessen H, et al. Challenges in end-of-life decisions in the intensive care unit: an ethical perspective. J Bioeth Inq 2013;10:93-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faber-Langendoen K, Lanken PN. Dying patients in the intensive care unit: forgoing treatment, maintaining care. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:886-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiegand DL, MacMillan J, dos Santos MR, et al. Palliative and End-of-Life Ethical Dilemmas in the Intensive Care Unit. AACN Adv Crit Care 2015;26:142-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andersen SK, Stewart S, Leier B, et al. Hastening death in Canadian ICUs: end-of-life care in the era of medical assistance in dying. Crit Care Med 2022;50:742-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, et al. Shared Decision Making in ICUs: An American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. Crit Care Med 2016;44:188-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kirchhoff KT, Song MK, Kehl K. Caring for the family of the critically ill patient. Crit Care Clin 2004;20:453-66. ix-x. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw DJ, Davidson JE, Smilde RI, et al. Multidisciplinary team training to enhance family communication in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2014;42:265-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Valade S, et al. A three-step support strategy for relatives of patients dying in the intensive care unit: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2022;399:656-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chou WC, Huang CC, Hu TH, et al. Associations between Family Satisfaction with End-of-Life Care and Chart-Derived, Process-Based Quality Indicators in Intensive Care Units. J Palliat Med 2022;25:368-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moss M, Good VS, Gozal D, et al. A Critical Care Societies Collaborative Statement: Burnout Syndrome in Critical Care Health-care Professionals. A Call for Action. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194:106-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- See KC, Zhao MY, Nakataki E, et al. Professional burnout among physicians and nurses in Asian intensive care units: a multinational survey. Intensive Care Med 2018;44:2079-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martins Pereira S, Teixeira CM, Carvalho AS, et al. Compared to Palliative Care, Working in Intensive Care More than Doubles the Chances of Burnout: Results from a Nationwide Comparative Study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162340. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro AF, Martins Pereira S, Gomes B, et al. Do patients, families, and healthcare teams benefit from the integration of palliative care in burn intensive care units? Results from a systematic review with narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2019;33:1241-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelson JE. Identifying and overcoming the barriers to high-quality palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2006;34:S324-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Imbulana DI, Davis PG, Prentice TM. Interventions to reduce moral distress in clinicians working in intensive care: A systematic review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2021;66:103092. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sprung CL, Ricou B, Hartog CS, et al. Changes in End-of-Life Practices in European Intensive Care Units From 1999 to 2016. JAMA 2019;322:1692-704. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ 2001;322:1297-300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Donaldson N. Relationship between three palliative care outcome scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- University of Wollongong Australia. Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 10]. Available online: https://www.uow.edu.au/ahsri/pcoc/

- Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. Refinement, scoring, and validation of the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) survey. Crit Care Med 2007;35:271-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mularski RA, Heine CE, Osborne ML, et al. Quality of dying in the ICU: ratings by family members. Chest 2005;128:280-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: evaluation of a quality-improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:269-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khandelwal N, Curtis JR. Economic implications of end-of-life care in the ICU. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014;20:656-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrando P, Gould DW, Walmsley E, et al. Family satisfaction with critical care in the UK: a multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028956. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerritsen RT, Jensen HI, Koopmans M, et al. Quality of dying and death in the ICU. The euroQ2 project. J Crit Care 2018;44:376-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamal AH, Bausewein C, Casarett DJ, et al. Standards, Guidelines, and Quality Measures for Successful Specialty Palliative Care Integration Into Oncology: Current Approaches and Future Directions. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:987-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leiter RE, Pu CT, Mazzola E, et al. Engaging Hospices in Quality Measurement and Improvement: Early Experiences of a Large Integrated Health Care System. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:866-873.e4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grudzen CR, Buonocore P, Steinberg J, et al. Concordance of Advance Care Plans With Inpatient Directives in the Electronic Medical Record for Older Patients Admitted From the Emergency Department. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:647-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blechman JA, Rizk N, Stevens MM, et al. Unmet quality indicators for metastatic cancer patients admitted to intensive care unit in the last two weeks of life. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1285-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerth AMJ, Hatch RA, Young JD, et al. Changes in health-related quality of life after discharge from an intensive care unit: a systematic review. Anaesthesia 2019;74:100-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyashita M, Morita T, Sato K, et al. A Nationwide Survey of Quality of End-of-Life Cancer Care in Designated Cancer Centers, Inpatient Palliative Care Units, and Home Hospices in Japan: The J-HOPE Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:38-47.e3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoyama M, Morita T, Kizawa Y, et al. The Japan HOspice and Palliative Care Evaluation Study 3: Study Design, Characteristics of Participants and Participating Institutions, and Response Rates. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34:654-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masukawa K, Aoyama M, Morita T, et al. The Japan hospice and palliative evaluation study 4: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, et al. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1133-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grunfeld E, Lethbridge L, Dewar R, et al. Towards using administrative databases to measure population-based indicators of quality of end-of-life care: testing the methodology. Palliat Med 2006;20:769-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Baal K, Schrader S, Schneider N, et al. Quality indicators for the evaluation of end-of-life care in Germany - a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of statutory health insurance data. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:187. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boddaert MS, Pereira C, Adema J, et al. Inappropriate end-of-life cancer care in a generalist and specialist palliative care model: a nationwide retrospective population-based observational study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022;12:e137-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bush RA, Pérez A, Baum T, et al. A systematic review of the use of the electronic health record for patient identification, communication, and clinical support in palliative care. JAMIA Open 2018;1:294-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curtis JR, Sathitratanacheewin S, Starks H, et al. Using Electronic Health Records for Quality Measurement and Accountability in Care of the Seriously Ill: Opportunities and Challenges. J Palliat Med 2018;21:S52-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindvall C, Lilley EJ, Zupanc SN, et al. Natural Language Processing to Assess End-of-Life Quality Indicators in Cancer Patients Receiving Palliative Surgery. J Palliat Med 2019;22:183-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindvall C, Deng CY, Moseley E, et al. Natural Language Processing to Identify Advance Care Planning Documentation in a Multisite Pragmatic Clinical Trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;63:e29-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masukawa K, Aoyama M, Yokota S, et al. Machine learning models to detect social distress, spiritual pain, and severe physical psychological symptoms in terminally ill patients with cancer from unstructured text data in electronic medical records. Palliat Med 2022;36:1207-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan A, Chien I, Moseley E, et al. Deep learning algorithms to identify documentation of serious illness conversations during intensive care unit admissions. Palliat Med 2019;33:187-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy S, et al. Quality measures for symptoms and advance care planning in cancer: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4933-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van Beek K, Woitha K, Ahmed N, et al. Comparison of legislation, regulations and national health strategies for palliative care in seven European countries (Results from the Europall Research Group): a descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:275. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mani RK, Amin P, Chawla R, et al. Guidelines for end-of-life and palliative care in Indian intensive care units' ISCCM consensus Ethical Position Statement. Indian J Crit Care Med 2012;16:166-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lind S, Wallin L, Brytting T, et al. Implementation of national palliative care guidelines in Swedish acute care hospitals: A qualitative content analysis of stakeholders' perceptions. Health Policy 2017;121:1194-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Palliative care [Internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 19]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care