Spiritual care for adult patients with cancer: from maintaining hope and respecting cultures to supporting survivors—a narrative review

Introduction

Background

Case

Ms. B was a 55-year-old female with history of stage IV pancreatic cancer. The patient was born and raised in Central America and had lived in the United States for ten years. The patient had metastatic disease at diagnosis and was treated with palliative-intent chemotherapy for almost a year before progression. When her cancer progressed, she developed weakness and burdensome symptoms that led to a series of hospital admissions. The patient and her supportive family repeatedly expressed their desire for the patient to remain at home. The treatment team had frequent conversations with the patient and her family about her disease and prognosis, which was estimated to be weeks to a few months. The treatment team recommended hospice care at home to provide the most support and wraparound care to help the patient remain at home. During these treatment planning discussions, the family repeatedly became frustrated and guarded, eventually leading to breakdown in the conversation. The collapse of the goals of care conversations perplexed the treatment team, who believed that the patient, the family, and team all had the same goal of keeping the patient at home.

As the patient became sicker and the communication between team and patient and family continued to stall, the team ordered a spiritual care consultation. A chaplain, a native Spanish speaker, assessed the situation. In discussion with the patient and her family, the chaplain uncovered the cultural and spiritual concerns causing the breakdown in goals of care conversations. The patient and her family explained they were offended when the treatment team shared a timeframe concerning the patient’s prognosis. They affirmed their belief the treatment team was providing excellent medical care, but it was God—and God alone—who would decide how much time the patient had left to live. For the patient and her family, any discussion of prognosis was ultimately a spiritual concern related to trust in God’s providential care.

Armed with this crucial information, the chaplain helped the treatment team better understand that treatment discussions involving prognostic considerations were a spiritual topic for the patient and her family. The chaplain provided the following suggestion for future goals of care conversations: after recommending hospice care as the best means for the patient to remain home, the treatment team could then share their intention to entrust the patient to God, who will decide how much time the patient will have to live.

The treatment team incorporated this advice into the next encounter with the patient and her family. The patient and her family agreed to the plan and felt the treatment team was respecting their spiritual and cultural beliefs. The patient was discharged home with hospice care, and she stayed home for the remainder of her life, surrounded by her family1.

Rationale and knowledge gap

Spiritual needs and adult patients with cancer: “The Why”

The available evidence paints a picture of religious decline in the United States. A 2021 Pew Research Center survey shows that 3 in 10 American adults are unaffiliated with an organized religion. Furthermore, the religiously unaffiliated share of the public increased by 6 percentage points during the five years prior to the survey, and 10 percentage points during the decade preceding the survey (1). Yet, the same survey revealed that 45% of Americans pray daily and 41% consider religion “very important” to their lives. According to an average of all 2021 Gallup polling, about three in four Americans identified with a specific religious faith, and 49% of Americans reported that religion is “very important” in their lives and 27% reported it is “fairly important” (2).

Furthermore, it is important not to conflate spirituality with religion. Spirituality is “a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred” (3). Religious communities, beliefs, and practices facilitate spirituality for many people, yet there are numerous people who experience spirituality outside of religion. Spirituality for these people can be found in nature, vocation, family, learning, community, and many other states or circumstances. Any person, regardless of religiosity (i.e., degree to which one follows a religion), can experience spirituality: spirituality is an essential part of being human (3-7).

A recent systematic review and analysis of evidence concerning “Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health” shows spirituality is important for most patients, spiritual needs are common, and patients desire that their medical teams attend to their spiritual care (8). In a study to assess spiritual needs in a racially, ethnically, and religiously mixed sample of hematology and oncology outpatients, 80% of patients reported at least one spiritual need (9). Other studies have shown over 90% of patients with cancer report at least one spiritual need (10,11) with one study showing multiple spiritual needs frequently co-existed (10). Furthermore, spiritual needs and concerns are present for patients with advanced cancer (11-17) as well as with survivors (18-22), with evidence that spiritual needs “occur independently from patients’ cancer characteristics as well as at any point of time during the disease trajectory” (4,10,23,24). Moreover, patients who identified as “spiritual but not religious” had higher levels of spiritual needs (9).

Despite their abundance among patients with cancer and other serious illnesses, spiritual needs are infrequently addressed in medical care. In one study, half of patients said they would welcome physician inquiry into their religious or spiritual needs, but less than 5% reported their physician had done so (9). In another study, 41% of patients desired a discussion of religious and spiritual concerns while hospitalized, but only half of those patients reported having a conversation with any member of the care team, and only 8% reported discussing religious and spiritual concerns with a physician (25). The data clearly shows patients want their physicians and medical teams to address their spiritual needs, yet this rarely happens.

There are many challenges that lead to the ongoing issue of minimizing and ignoring the spiritual needs of patients in medical settings (8,13,16,26,27); insufficient training and time are the barriers most commonly cited by physicians (16,27). The lack of responsiveness to the spiritual needs of patients with cancer carries risk for these patients. For example, patients whose spiritual needs are overlooked have higher rates of depression and a reduced sense of spiritual meaning and peace (11) as well as lower ratings of satisfaction with care received (26). This also affects quality measures, like reduced hospice usage and increased aggressive treatment at end of life for patients with advanced cancer in comparison to patients whose spiritual needs were supported by the treatment team (28). Inadequate spiritual care for patients with cancer have been shown to increase end-of-life medical costs, especially for minorities and patients for whom religion is a significant coping mechanism (29).

Addressing the spiritual needs of patients has also been shown to be beneficial in providing patient-centered health care. For instance, one study showed patients who had religious and spiritual discussions while hospitalized were more likely to give a positive assessment of their care at the highest level on four different measures of patient satisfaction, including rating overall care received as excellent as well as confidence and trust in physicians. The latter was true even for patients who did not initially desire a discussion of their religious or spiritual issues (25). Furthermore, as previously indicated, studies have shown that when spiritual care is provided by the treatment team to patients with advanced cancer, this has led to higher rates of hospice utilization and better patient quality of life near death (28) as well as fewer aggressive interventions at end of life and fewer intensive care unit (ICU) deaths (8,30), all of which are important quality measures closely monitored by hospitals, cancer centers, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. A meta-analysis identified the importance of spirituality and religion on the physical, mental, and social well-being of patients with cancer. For instance, affective or the subjective emotional dimension of spirituality and religion, such as a sense of transcendence, meaning, purpose, and connection as well as struggle with or anger with God, were associated with physical well-being, functional well-being, physical symptoms (31), emotional well-being, general distress, depression (32), and social health (33).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines include recommendations for spiritual care assessments (34). Likewise, the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care lists Spirituality as a Domain of Care which requires screening, assessment, treatment, and ongoing care by the Palliative Care Interdisciplinary Team (35,36).

Objective

We will review “Who” from the treatment team should provide spiritual care to patients as well as a means of “How” to do so. We will also review how addressing patients’ spiritual needs helps patients maintain hope, enhances the medical decision-making process, and supports survivors. We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1274/rc).

Methods

Search strategy

The search strategies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | August 1, 2022 |

| Databases and other sources searched | Electronic PubMed (pubmed.gov) |

| Search terms used | “Spirituality”, “Spiritual Care”, “Cancer”, “Adult”, “Palliative Care” |

| Timeframe | 2000–2022 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Included published articles regardless of study design or outcomes, which discussed spirituality within serious illness and focused on adult oncology. We excluded articles which discussed pediatric spiritual care and oncology, and articles not in English. We did not include all literature in the field |

| Selection process | Articles were screened by a single reviewer. If the inclusion or exclusion criteria was not clear at the title/abstract screening stage, two reviewers screened and discussed the articles |

“Who” addresses the spiritual needs of patients?

While chaplains routinely address the spiritual needs of patients, patient-centered care requires the entire treatment team be capable of considering a patient’s spirituality to best optimize a patient’s treatment and quality of life (37). An interprofessional approach to spiritual care in oncology is the most effective way to support patients’ needs (5,38). Handzo and Koenig assert many members of the treatment team can operate as spiritual care generalists who can do spiritual screenings and histories as well as make appropriate referrals to spiritual care specialists, such as board-certified chaplains, when more in-depth and complex spiritual care is needed (39). The whole treatment team should take the initiative to offer spiritual care with a multi-disciplinary approach to the address the spiritual needs and concerns of patients in the health care setting and, more specifically, for patients with cancer (3,5,38,40).

In addition to completing spiritual screenings, spiritual care generalists can also provide spiritual support to patients. Craigie describes how, through intention, presence with, and their regard for patients, spiritual care generalists can bring a spirit of compassion and acceptance into their encounter with a patient. The specific content, expertise, or technique used is less important than the connection created with the patient that allows the clinician to bear witness and accompany their patients in their spirituality (41). Compassion is a spiritual practice, an attitude, and a way of approaching the needs of others and helping others in their suffering; every member of the treatment team can practice compassion as a form of spiritual care (3). “Cancer patients do not expect spiritual solutions from oncology team members, but they wish to feel comfortable enough to raise spiritual issues and not be met with fear, judgmental attitudes, or dismissive comments” (42). Patients can refuse the offer of spiritual care as part of patient-centered care, but every patient should be screened for potential spiritual needs, offered the possibility of spiritual care, and receive a spirit of compassion and regard from their clinicians.

“How”

Spiritual care specialists, such as board-certified chaplains, utilize spiritual assessment as a key aspect of their more in-depth spiritual care (43). There are several excellent spiritual assessment approaches available for use within health care settings, including the Spiritual Assessment and Intervention Model (Spiritual AIM) (44) and the PC-7, which provides a quantifiable assessment of spiritual concerns for patients receiving palliative care near end of life (45). The Spiritual Assessment model we use in our daily chaplaincy practice is the Outcome-Oriented Chaplaincy (OOC) approach as elucidated by Brent Peery (46,47) and based on the work of Art Lucas (48). OOC is designed for the work of chaplains on the treatment team, but we believe this model of spiritual assessment and care can also be effective for all members of the treatment team in their work with patients.

Before proceeding, we want to acknowledge some spiritual care specialists are critical of an outcome-oriented approach to spiritual care, preferring a process-oriented model of spiritual care which focuses on personal competence, presence, and relationship-building (49). In the process-oriented approach, forging a caring relationship without a focus on problem-solving or any pre-determined goals is paramount. Being rather than doing enables the formation of a healing relationship, which is effective spiritual care in the process model (49).

Yet, process-oriented chaplaincy still requires assessment, interventions, and outcomes in the cultivation of a healing relationship (46,49). In our professional practice, we are convinced, as argued by Damen and colleagues, that process and outcomes are both integral aspects of spiritual care which focus on the “vision of the good” in the care of the patient (49). We believe OOC, as elucidated below, operates within a process of forging a caring relationship with patients in order for outcomes to be achieved. Additionally, one of the benefits of OOC is how it can be utilized to incorporate the insights of other assessment models (46).

The primary components of OOC include assessment, interventions, and outcomes (47). The chaplaincy assessment identifies the needs, hopes and resources of four key domains: spiritual, emotional, relational, and biomedical. While the focus is on spirituality, there is significant overlap with the other domains since spirituality is profoundly related to meaningful connections; meaningful connections with the self, others, and the transcendent contribute to spiritual, emotional, relational, and biomedical health (46).

Lucas emphasized the importance of going beyond assessing the needs of patients to prevent having a pathological focus and creating a dichotomy in which the patient has all the needs, and the caregiver has all the resources. Instead, helping patients recognize they have hopes and resources with which they can support themselves in times of crisis can help facilitate healing. The hopes of patients can pull them forward, providing energy, direction, impetus, and motivation for the future. Spotlighting the patient’s hopes and resources uplifts the person and promotes healing (48).

Overall, the OOC provides a helpful framework for perceiving four domains of complex human experience—the spiritual, emotional, relational, and biomedical—and to assess the relative proportionality of needs, hopes, and resources within each domain (46).

Spiritual needs

Spirituality is expressed through relationships of all kinds, with oneself, other people, community, nature, and the divine or the transcendent (44). Cancer frequently makes people disconnect from oneself, others, nature, and the sacred. Cancer has vast negative implications for individuals and can deprive someone of mental clarity, functional ability, opportunities to be in contact with others, or productivity through employment or vocation. Cancer also forces patients to face mortality. All these changes can lead to disruption in one’s varied relationships (50).

In our work with patients with cancer, we have frequently encountered patients who have lost a sense of self. Losing their ability to work or remain employed can lead to an identity crisis. Their perceived lack of meaningful work, a sense of satisfaction from a job well-done, praise from bosses, paychecks, and the admiration of peers has led them to question the meaning of their life. Some patients share they are used to being the caretaker in their families but now “I have to ask for help” or “I don’t want to be a burden.” A young patient with metastatic bladder cancer said, “I feel like such a loser,” because she was no longer able to work like other women her age.

In addition, many patients describe a rupture in their familial relationships due to the limitations their cancer creates. Cancer prevents some people from being present for important events such as graduations and weddings. Other patients are unable to enjoy eating with loved ones because of changes in their sense of taste or inability to swallow. Patients with cancer report physical intimacy with partners frequently suffers. Other patients describe not having the stamina to interact with their active children and grandchildren, and thus isolation builds. An inability to be in nature, to go camping or hiking or swimming in a lake has left some feeling bereft, with cancer stealing from them a key aspect of their life. Some describe a disconnection with the transcendent; expressing anger with God, feeling punished by God, the unfairness of life or feeling unsafe in the universe are all common reactions to a cancer diagnosis. Losing hair, being in a wheelchair, or having scars often alters an individual’s self-perception, such that they no longer recognize their former self. “I don’t recognize the person looking at me in the mirror” is a common statement. These limitations make patients feel disconnected from self, others, nature, and the sacred. These relational disruptions are spiritual needs.

The relationality present in the spiritual needs of cancer patients carry significant weight and importance throughout an individual’s illness. For instance, patients with advanced cancer desire recognition as a whole person until the end of their life (12). Spiritual needs for patients of cancer and their caregivers identified in another study included relating to an Ultimate Other, giving and receiving love from other persons, and creating meaning and purpose (51). A different study emphasized the relationality of spiritual needs with four themes of connection, seeking peace, meaning and purpose, and transcendence including the importance of relationship with the Divine (52). Two of the most strongly and frequently stated spiritual needs of patients with cancer in another analysis were to “plunge into the beauty of nature” and “to turn to someone in a loving attitude”. This study also showed a high endorsement of needs which reflect the act of giving, which the authors of the study linked to the needs to give and receive love, feel connected to the social environment, and to perceive oneself as a valuable person despite the disease (10).

A key response to spiritual needs is embodiment or being in relationship with the patient. This embodiment can facilitate healing. Shields, Kestenbaum, and Dunn, through their Spiritual AIM (45), identify how the embodied roles of being guide, valuer, or truthteller can lead to healing of spiritual needs. If a patient’s primary spiritual need is meaning and direction, the embodied role of guide can facilitate the patient achieving greater clarity, concerning goals of care or the meaning of one’s life. If a patient’s primary spiritual need is self-worth and belonging, the embodied role of valuer can help the patient feel more worthy. If a patient’s primary spiritual need is reconciliation, the embodied role of truth-teller can help hold the patient accountable for greater responsibility and humility (45). While chaplains are trained to provide this embodiment to patients, other members of the treatment team can also play this role.

A case example of this embodiment was a 50-year-old man with advanced cancer who described himself as “not religious” but wanted to visit with a chaplain. Once rapport existed between patient and chaplain, the patient revealed great spiritual distress. He shared that he was raised Catholic but had not been practicing his faith or even thought much about God during his adult years. Now, as he faced his mortality, he longed to be reconciled to God. Yet he felt he would be a “hypocrite” if he turned to God as he approached death after “ignoring” God for much of his life. The chaplain embodied being a guide as he led the patient to explore his images of God. The patient, over-time, more fully embraced his image of God as a “loving father”. The image led to a breakthrough for the patient who was a parent himself, and was able to see that, just as he would always act with love, mercy, and acceptance toward his children, so God would do the same with him. Through work with the chaplain and a visit with a Catholic priest for sacramental care, the patient expressed reconciliation with God. The patient felt an incredible sense of relief and was then able to focus his remaining time with his family, unburdened by the spiritual distress he had been enduring since his diagnosis.

“Hopes”

Lucas discusses two different types of hope: intermediate and ultimate hope. Intermediate hope focuses on a future with preferred outcomes, such as a favorable test result, restored function, or financial stability. Ultimate hope transcends any particular set of present or future circumstances, and involves confidence in one’s future, rooted in the good care and provision of the divine, fate, self, society, or other forces (46,48). It is natural for humans to experience both types of hope simultaneously. When a patient only expresses intermediate hopes—great computed tomography (CT) scan results, chemotherapy successes—that are medical unlikely, problems arise. A provider can explore the patient’s ultimate hopes as a potential source of support in these situations (46), as exemplified in the following case. A 63-year-old man with metastatic colorectal cancer identified as atheist and had strong hopes for a “complete recovery” despite his medical team repeatedly discussing that the intent of his treatment was palliative. He expressed a series of intermediate hopes regarding each CT scan, physical therapy series, and lab test that they would reveal a favorable outcome and his functional status would return to normal. Over time, the patient’s prognosis worsened, and through his relationship with a chaplain, the patient began to explore what hope would look like given cure was not possible. The patient shared with the chaplain his belief each person contains a spark of the life energy present in the universe. The patient began to find an ultimate hope that, when he died, his spark of energy would return to the universe and continue to be a part of the life-force animating our world. He also found ultimate hope in watching the legacy of his life through his children and grandchildren who would live on after he died. Finding a sense of ultimate hope allowed this patient to find comfort and to die with peace.

Maintaining hope is important for cancer patients to minimize suffering. Elements which promote the experience of hope among cancer patients are to give and receive love, have faith in God, believe in life after death, connect with family and friends, have short-term and long-term goals, maintain autonomy wherever possible, and feel supported and have a good relationship with clinicians (24). The latter shows the importance of the treatment team in attending to the experience of hope for patients.

“Resources”

Perry defines resources as assets people use in coping with the challenges in their lives while also categorizing resources into intrapersonal, interpersonal, and suprapersonal. Intrapersonal resources include courage, experience, humility, knowledge, maturity, self-awareness, wisdom, and more. Interpersonal resources are relationships between persons and contribute to the well-being of the patient; unhealthy relationships create needs, healthy relationships are resources. Suprapersonal resources transcend individuals and are accessed through trust in a power or powers beyond oneself. Suprapersonal resources can be theistic or atheistic, often described as grace, luck, blessings, and fortune. Suprapersonal resources are the gifts of a higher power, society, ancestors, and/or the universe (46).

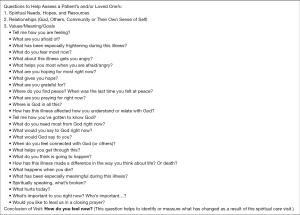

A key way treatment team members can support patients with cancer is to explore with them how they can connect to the resources they already possess. We engage in this kind of exploration by asking patients about activities and people of deep meaning, value, enjoyment, and support in their lives (see Table 2).

Table 2

| Meaningful activity | Resource |

|---|---|

| Handicrafts | Knitting a sweater for each grandchild |

| Painting | Painted greeting cards while hospitalized to alleviate anxiety |

| Writing | Write family history as a legacy project |

| Spending time with young grandchildren in their preferred activities | Visit a zoo using an electric scooter |

| Love of nature | Picnic in a local park instead of hiking |

| Prayer | Using a prayer journal to process fear and anxiety, as well as gratitude and hope |

| Career as a nurse | Use wisdom gained through prior work to guide experience of illness and feel connected to care team |

| Religion | Lean into a sense of trust in the beneficence of God and the universe |

Respecting culture: medical decision-making

Using the definition of culture as “the values, beliefs and behaviors that a people hold in common, transmit across generations, and use to interpret their experiences” (53-55), spirituality and religion are essential aspects of the cultural matrix (55-57). Spiritual and religious beliefs and practices are common to humanity, relate to health, sickness, death, and healing (55), and play an important role in medical decision-making for many people. A study exploring how religion affected cases in which existed conflict over life-sustaining treatment (LST) showed that when religion was central to LST conflict, a specific constellation of sociodemographic factors was present. Religion was more likely to be central to the conflict in cases involving patients who were non-white (62.5% vs. 31.0%), who did not speak English as a primary language (41.7% vs. 13.1%), were born outside of the USA (62.5% vs. 31.0%) and were lower income (25.0% vs. 7.0%). Religion manifested itself in these cases in three ways: a strong belief in miracles or insisting decisions were in “God’s Hands”, disagreements about religious doctrine regarding medical treatment, and strong religious and cultural notions and beliefs that differed from the dominant American medical perspectives (58). The authors of this study suggested there may be a cultural component to the role of religion in conflict over LST. The belief God is in control or outcomes are “in God’s Hands” can lead to discord when clinicians ask patients or surrogates to make medical decisions, but the patient or surrogate does not believe the decision is one for a human being to make. Additionally, death and dying are often experienced as a spiritual event rather than a medical one, so religious beliefs can be invoked to resist the medical components of death (58).

The spiritual and religious dimension of cultural influence on medical decision-making is underscored in a study of patients with advanced cancer. Patients with advanced cancer who were closely connected to religious communities were less likely to receive hospice care and more likely to receive aggressive end-of-life measures, and die in an intensive care unit. The latter risks were especially pronounced among high religious coping and racial and ethnic minority patients. Conversely, patients well-supported by religious communities who also received spiritual support and end-of-life discussions from the treatment team were associated with higher rates of hospice, fewer aggressive interventions, and fewer ICU deaths (29). These results imply that the content of spiritual care provided to patients matters. The spiritual care provided by the treatment team is more biomedically informed and therefore end-of-life discussions can incorporate both the patients’ spiritual priorities and the medical realities. When treatment teams are willing to engage the spiritual and religious factors influencing a patient’s end-of-life medical decisions, this engagement has the potential to help patients move from resistance to acceptance and spiritual peace in the dying process. When the treatment team does not try to change patients or their loved ones’ minds on their spiritual or religious beliefs and values, but rather focuses on helping them find a way to hold to their beliefs and values as they transition to hospice or comfort care, patients and caregivers feel heard and respected. This allows the treatment team to respect the patient’s culture while also providing the most appropriate medical care (28).

Cultural humility is fundamental for the medical team when engaging patients and their loved ones in the medical decision-making process. When practicing cultural humility, the treatment team relinquishes the role of the expert and allows the patients and families to be the expert of that individual, guiding the decision-making process through their own lenses (59,60). Each patient and their loved ones are shaped by their cultural matrix and are “a self-defined web of meaning… unique to each person, comprised of a composite of beliefs and values, a fabric woven by way of one’s life narrative” (56). The treatment team must be willing to hear the patient and their loved ones, honor the beliefs and values they express, and help them find a way to authentically uphold their beliefs while avoiding harm and providing the best care possible.

Conflict around LST may also be a reflection of distrust in the health system, and religious beliefs may be invoked by patients and families to assert power in otherwise powerless circumstances (58). For example, “miracle-talk” from patients and families during goals of care conversations may indicate deeper issues of distrust of the treating team. In these situations, the treatment team should practice humility and listen deeply to identify the root of the mistrust, affirm the expressed emotional distress, and help patients and their loved ones find adaptive coping mechanisms (61).

Ultimately, the most effective way for medical providers to respect spiritual and religious dimensions of culture during medical-decision-making is to listen to and genuinely attempt to understand who the patient and their loved ones are as people and what is important to them. Johnson et al. describe this approach as follows: “In affirming someone’s life by asking who they are first and subsequently what is important to them, we demonstrate empathy. This lays the groundwork for more difficult conversations and prepares us for the response. It will also allow us to make recommendations from a place of awareness, which can set the foundation for trust; the kind of trust that bridges differences in culture, ethnicity, and religion.” (60). While culture is broader and more nuanced than spiritual or religious considerations alone, these aspects of culture must be respected and recognized by treatment teams in order to support patients and move forward medical decision-making.

Supporting survivors

Patients with cancer have spiritual and religious needs from the time of diagnosis throughout their disease trajectory. While the role of spiritual care at end of life is well defined, it is also important to consider the role of spirituality in patients who survive cancer. Numerous studies illustrate that spiritual well-being and faith leads to better quality of life, less distress, improved post-traumatic growth, and improved relationships with physicians in cancer survivors (18-22). Conrad et al. describe how spiritual resources can help cancer survivors creatively reframe, seek acceptance, and finding meaning through the experience of living with and surviving cancer. Spiritual practices such as meditation, reflection, journaling, prayer, and ritual can help make space for and process the intense emotions patients experience on the journey with cancer in ways which align with one’s values. Survivors can nourish spiritual well-being by fostering meaning and purpose, deepening connections, and honoring the need for reconciliation and forgiveness (62). An 82-year-old man whose esophageal cancer had been cured shared with a chaplain his spiritual distress as a survivor of cancer. He repeatedly asked himself “why” he survived while others did not. He also shared “I must be alive for a reason” but expressed bafflement as to his purpose in life. In working with a chaplain, he came to a place where he found peace in the reality contained in this statement from the patient; “I am here; I am loved and I love my family and friends, and that is enough for now.”

The strengths of this narrative review include a comprehensive literature search on the spiritual needs of adult patients with cancer as well as the conceptual expertise and clinical experience of the authors. The relevance of the research and literature is brought to life through the cases presented as well as through authors’ practical knowledge. The limitation of this review is that it does not include all the literature in the field.

Conclusions

Patients with cancer and their loved ones can experience a broad range of spiritual needs from the time of diagnosis through the disease trajectory to death or survival (63). Recognizing and validating an individual’s spiritual needs can allow the medical team to connect more deeply with a patient and help maximize support from within an individual, their close circle, and the greater community (Figure 1) (64). General spiritual care is the responsibility of all members of the medical team, and whenever possible, engaging a dedicated spiritual care consultant allows for more effective, meaningful and goal concordant care for patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Annals of Palliative Medicine, for the series “Palliative Care in GI Malignancies”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1274/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1274/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1274/coif). The series “Palliative Care in GI Malignancies” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. Dr. KA served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

1, the cases presented in this article come from the authors’ clinical experience, names and details in the cases have been changed to preserve privacy.

References

- Pew Research Center. About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Are Now Religiously Unaffiliated. Accessed July 29, 2022. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/12/14/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-are-now-religiously-unaffiliated/

- Gallup. How Religious are Americans? Published December 23, 2021. Accessed August 2, 2022. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/358364/religious-americans.aspx

- Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, et al. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med 2014;17:642-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol 2012;23:49-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puchalski CM, Sbrana A, Ferrell B, et al. Interprofessional spiritual care in oncology: a literature review. ESMO Open 2019;4:e000465. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hill PC, Pargament KI, Hood RW Jr, et al. Conceptualizing Religion and Spirituality: Points of Commonality, Points of Departure. J Theory Soc Behav 2000;30:55-7. [Crossref]

- Rodolfo D, Peres M, Sena M. Conceptualizing Spirituality and Religiousness. In: Lucchetti G, Peres M, Damiano R, eds. Spirituality, Religiousness, and Health: From Research to Clinical Practice. Vol 4 of Religions, Spirituality, and Health: A Social Scientific Approach. Springer, 2019:3-10.

- Balboni TA, VanderWeele TJ, Doan-Soares SD, et al. Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health. JAMA 2022;328:184-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Astrow AB, Kwok G, Sharma RK, et al. Spiritual Needs and Perception of Quality of Care and Satisfaction With Care in Hematology/Medical Oncology Patients: A Multicultural Assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:56-64.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Höcker A, Krüll A, Koch U, et al. Exploring spiritual needs and their associated factors in an urban sample of early and advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2014;23:786-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pearce MJ, Coan AD, Herndon JE 2nd, et al. Unmet spiritual care needs impact emotional and spiritual well-being in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2269-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vilalta A, Valls J, Porta J, et al. Evaluation of spiritual needs of patients with advanced cancer in a palliative care unit. J Palliat Med 2014;17:592-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rohde G, Kersten C, Vistad I, et al. Spiritual Well-Being in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Receiving Noncurative Chemotherapy. Cancer Nursing 2017;40:209-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bovero A, Leombruni P, Miniotti M, et al. Spirituality, quality of life, psychological adjustment in terminal cancer patients in hospice. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016;25:961-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tarakeshwar N, Vanderwerker LC, Paulk E, et al. Religious coping is associated with the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 2006;9:646-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Amobi A, et al. Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:461-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Guay MO, Chisholm G, Williams J, et al. Frequency, intensity, and correlates of spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients assessed in a supportive/palliative care clinic. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:341-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johannessen-Henry CT, Deltour I, Bidstrup PE, et al. Associations Between Faith, Distress and Mental Adjustment-a Danish Survivorship Study. Acta Oncologica 2013;52:364-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gesselman AN, Bigatti SM, Garcia JR, et al. Spirituality, emotional distress, and post-traumatic growth in breast cancer survivors and their partners: an actor-partner interdependence modeling approach. Psychooncology 2017;26:1691-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canada AL, Murphy PE, Fitchett G, et al. Re-Examining the Contributions of Faith, Meaning, and Peace to Quality of Life: A Report From the American Cancer Society’s Studies of Cancer Survivors-II (SCS-II). Ann Behav Med 2016;50:79-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wildes KA, Miller AR, de Majors SS, et al. The religiosity/spirituality of Latina breast cancer survivors and influence on health-related quality of life. Psychooncology 2009;18:831-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez P, Castañeda SF, Dale J, et al. Spiritual well-being and depressive symptoms among cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:2393-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim Y, Yen IH, Rabow MW. Comparing Symptom Burden in Patients with Metastatic and Nonmetastatic Cancer. J Palliat Med 2016;19:64-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ripamonti CI, Miccinesi G, Pessi MA, et al. Is It Possible to Encourage Hope in Nonadvanced Cancer Patients? We Must Try. Ann Oncol 2016;27:513-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams JA, Meltzer D, Arora V, et al. Attention to Inpatients’ Religious and Spiritual Concerns: Predictors and Association with Patient Satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1265-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Astrow AB, Wexler A, Texeira K, et al. Is Failure to Meet Spiritual Needs Associated with Cancer Patients’ Perceptions of Quality of Care and Their Satisfaction with Care? J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5753-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Best M, Butow P, Olver I. Doctors discussing religion and spirituality: A systematic literature review. Palliat Med 2016;30:327-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:445-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balboni T, Balboni M, Paulk M, et al. Support of Cancer Patients’ Spiritual Needs and Associations With Medical Care Costs at the End of Life. Cancer 2011;117:5383-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balboni TA, Balboni M, Enzinger AC, et al. Provision of spiritual support to patients with advanced cancer by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1109-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jim HS, Pustejovsky JE, Park CL, et al. Religion, spirituality, and physical health in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer 2015;121:3760-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salsman JM, Pustejovsky JE, Jim HS, et al. A meta-analytic approach to examining the correlation between religion/spirituality and mental health in cancer. Cancer 2015;121:3769-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sherman AC, Merluzzi TV, Pustejovsky JE, et al. A meta-analytic review of religious or spiritual involvement and social health among cancer patients. Cancer 2015;121:3779-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Handzo G, Bowden JM, King S. The Evolution of Spiritual Care in the NCCN Distress Management Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019;17:1257-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th edition. Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. 32-5. Available online: https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B. Making Health Care Whole: Integrating Spirituality Into Patient Care. Templeton Press: 2010:17-20.

- Hall E, Hughes B, Handzo G. Spiritual Care: What It Means, Why It Matters in Health Care. Spiritual Care Association White Paper. 2016:7-11. Available online: https://www.spiritualcareassociation.org/white-paper-spiritual-care.html

- Puchalski CM, Lunsford B, Harris MH, et al. Interdisciplinary spiritual care for seriously ill and dying patients: a collaborative model. Cancer J 2006;12:398-416. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Handzo G, Koenig HG. Spiritual care: whose job is it anyway? South Med J 2004;97:1242-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Craigie FC. Spiritual Caregiving by Health Care Professionals. Health Progress Journal of the Catholic Health Association of the United States. 2007;88:61-4.

- Surbone A, Baider L. The spiritual dimension of cancer care. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2010;73:228-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- For example, see the Standards of Practice for Professional Chaplains, Section 1 Standard 1 from the Association of Professional Chaplains. Accessed 25 August 2022. Available online: https://www.professionalchaplains.org/content.asp?pl=200&sl=198&contentid=514

- Shields M, Kestenbaum A, Dunn LB. Spiritual AIM and the work of the chaplain: a model for assessing spiritual needs and outcomes in relationship. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:75-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fitchett G, Pierson A, Hoffmeyer C, et al. Development of the PC-7, a Quantifiable Assessment of Spiritual Concerns of Patients Receiving Palliative Care Near the End of Life. J Palliat Med 2020;23:248-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perry B. Outcome Oriented Chaplaincy: Perceptive, Intentional, and Effective Caring. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2020.

- Perry B. Outcome Oriented Chaplaincy: Intentional Caring. In: Roberts S, ed. Professional Spiritual and Pastoral Care: A Practical Clergy and Chaplain’s Handbook. SkyLight Paths 2012:342-61.

- Lucas A. Introduction to The Discipline for Pastoral Care Giving. In: VandeCreek L, Lucas A. Eds. The Discipline for Pastoral Care Giving: Foundations for Outcome Oriented Chaplaincy. Haworth Press 2001:1-18.

- Damen A, Schuhmann C, Leget C, et al. Can Outcome Research Respect the Integrity of Chaplaincy? A Review of Outcome Studies. J Health Care Chaplain 2020;26:131-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swinton J. Healing in Pastoral Care. In: Coakley S. Spiritual Healing: Science, Meaning, and Discernment. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2020:205-30.

- Taylor EJ. Spiritual needs of patients with cancer and family caregivers. Cancer Nurs 2003;26:260-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hatamipour K, Rassouli M, Yaghmaie F, et al. Spiritual needs of cancer patients: a qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care 2015;21:61-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perkins HS, Geppert CM, Gonzales A, et al. Cross-Cultural Similarities and Difference in Attitudes About Advance Care Planning. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:48-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perkins HS, Hazuda HP. Cross-cultural medical ethics. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14:778. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fukuyama MA, Sevig TD. Cultural diversity in pastoral care. J Health Care Chaplain 2004;13:25-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anderson RG. The search for spiritual/cultural competency in chaplaincy practice: five steps that mark the path. J Health Care Chaplain 2004;13:1-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frame MW. Forging spiritual and cultural competency in spiritual care-givers: a response to Fukuyama and Sevig and Anderson. J Health Care Chaplain 2004;13:51-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bandini JI, Courtwright A, Zollfrank AA, et al. The role of religious beliefs in ethics committee consultations for conflict over life-sustaining treatment. J Med Ethics 2017;43:353-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved 1998;9:117-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson KA, Quest T, Curseen K. Will You Hear Me? Have You Heard Me? Do You See Me? Adding Cultural Humility to Resource Allocation and Priority Setting Discussions in the Care of African American Patients With COVID-19. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:e11-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shinall MC Jr, Stahl D, Bibler TM. Addressing a Patient’s Hope for a Miracle. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:535-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Conrad S, Cohen J. Spiritual Care for Survivors of Cancer. Coping with Cancer. September/October 2018. Accessed 1 September 2022. Available online: https://copingmag.com/spiritual-care-for-survivors-of-cancer/

- Ripamonti CI, Giuntoli F, Gonella S, et al. Spiritual care in cancer patients: a need or an option? Curr Opin Oncol 2018;30:212-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matthew Jacobson, MDiv, BCC. Personal Consultation, November 4, 2022.