Bereavement care reimagined

Introduction

“Finally, one day the aged father of a Prairie du Sac woman will die. And next-door neighbours will not drop by because they don’t want to interrupt the bereavement counsellor. The woman’s kin will stay home because they will have learned that only the bereavement counsellor knows how to process bereavement in the proper way. The local clergy will seek technical assistance from the bereavement counsellor to learn the correct form of service to deal with guilt and bereavement. And the grieving daughter will know that it is the bereavement counsellor who really cares for her because only the bereavement counsellor comes when death visits this family on the prairie.

It will be only one generation between the time the bereavement counsellor arrives, and the community of mourners disappears. The counsellor’s new tool will cut through the social fabric, throwing aside kinship, care, neighbourly obligations, and community ways of coming together and going on. Like John Deere’s plough, the tools of bereavement counselling will create a desert where a community once flourished.” (1).

In his annual lecture to the Schumaker Society, John McKnight, founder of Asset Based Community Development (ABCD) and the ABCD Institute, compared the development of professional bereavement support to that of the cast iron plough of 1837. The advent of the plough was seen as a technological advancement, making life better and easier for the farming community and increasing the production of food, but the unintended consequences leaves behind a farming wasteland. Comparing the growth of professional bereavement services to a similar process to that of the development of the plough might seem a little far fetched. However, the five points of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (2) reveal the underlying processes that bring the analogy to light. The five action points are

- Building healthy public policy;

- Creating supportive environments;

- Strengthening community action;

- Developing personal skills;

- Re-orienting health care services toward prevention of illness and promotion of health.

Applying the example of John McKnight, he posits that the professionalisation of grief and loss has decreased the development of supportive environments, decreased the strength of community action, and decreased personal skills, particularly of community members supporting others who are grieving. Furthermore, health services have orientated themselves around professional care and this has been supported by healthcare policy.

McKnight’s analogy is no idle or idealized imagery from someone vested in anti-professionalism. His analogy is based on historical and sociological facts and observations about bereavement support, even in comparatively recent times (3-5). The care of bereaved people is widely acknowledged to have become professionalised—and a service that is not only limited in its reach but also questionable in its clinical effectiveness (6,7). The cultural rituals of community grieving, and the warm heartedness that went with them, are no longer widely present. Instead, both people affected and the professional services who support them reach for professionalised bereavement support as the first port of call. This leaves behind a wilderness of grieving, lonely people who do not know where to go next other than overstretched professional bereavement services.

Professional grief support, whether this be one-to-one consultations or group-led, has become the primary route of referral for those affected by grief and loss. The discussion in this paper considers how support is embedded into the web and waft of healthy communities. Further, communities are not limited to neighbourhoods, but includes civic bodies such as educational institutions, workplaces, places of worship and others outlined in the Compassionate City Charter (8). Because bereavement to grief is a natural and universal reaction to loss, we argue that all societies must have integrated support responses within all civic structures. Contrary to some professional opinion, this does not mean bereavement services in all civic institutions but rather member responses to losses within those institutions devised and enacted by those members—students for students, employees for employees, neighbours for neighbours, and so on. Palliative care services have undervalued these community forms of support, with the unfortunate reality that most health service programs can actively disrupt rather than support these informal networks (9,10). Our aim in this paper is to describe how this ideal could be achieved now, through the application of current health promotion methodologies inspired by the above Ottawa Charter principles. We begin this paper by briefly describing the current policy and practice challenge before summarizing some of the important evidence for the effectiveness of health promotion responses. We will then conclude the paper with recommendations for future work and development.

The current challenge

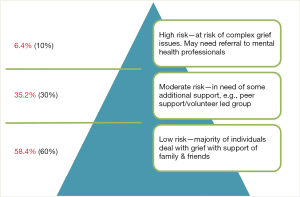

Penny and Relf’s model for bereavement, used for commissioning bereavement services, is drawn from the work of Aoun et al. who proposed a three-tiered risk model (11).

This model, adopted by Penny and Relf (12), has been used by the National Bereavement Alliance in their guidance on commissioning bereavement services. Estimates of those who are at high risk, between 5% and 10%, require professional one to one support. A further 35% are thought to need professional support that may be at arms length or non specialist help. However, 100% of people need the love, laughter and friendship found amongst family, friends and community members. Furthermore, these estimates are based on current prevalence of existing bereavement supports. It does not consider the impact community sources of bereavement care might have, were they universally available. Anecdotal evidence suggests that even severe bereavement reactions can be transformed through community support (13) which in turn can decrease the need for professional support.

Professional services, whether specialist or generalist, do not see that they have a role in building communities of support and assume the community will do this on its own. But these same community supports are undermined by the development of specialist bereavement services. Furthermore, professionals may argue, any form of bereavement support should be overseen by professional services. Community supports, including community run bereavement groups, may not know how to help people who feel suicidal and therefore they are not safe to run their own groups. This leads to paralysis, where recreation of traditional forms of support are discouraged because of risk aversion.

Support for people who are grieving has always been part of human history and culture. Professional bereavement services are but a blink of the eye of recent human history (14). In the modern world, new forms of these traditional ways of grieving are being invented. There are now a number of festivals of grief, both on line and in person, where mutual support sits alongside professional advice. On line communities such as The Grief Gang Instagram and podcast started by Amber Jeffrey helps find a voice for young people who are grieving. The New Normal Charity, started by two young men who both lost their fathers and wanted to find a place to talk about this, meets both on line in person. Public Health Palliative Care practice is clear. Bereavement support starts in the community. It is contained in our workplaces, our institutions, our places of worship and the other domains described in the Compassionate City Charter (8). An important part of bereavement support is the kindness of one person to another during a time of loss, which does not need professional permission or supervision. Professional services need to participate in stimulating these community sources of support, without guiding, without interference and without taking control.

Bessell van Der Kolk and Sky (15) summarises the importance of human connection:

“Social support is not the same as merely being in the presence of others. The critical issue is reciprocity, being truly heard and seen by the people around us, feeling that we are held in someone’s mind and heart. For our physiology to calm down, heal, and grow we need a visceral feeling of safety. No doctor can write a prescription for friendship and love. These are complex and hard earned capacities.” (15).

Building compassionate communities and cities for the future

Compassionate communities and cities are respectively community development and social ecology initiatives from the stable of the ‘new’ public health, i.e., health promotion. They are both ‘bottom up’ and ‘top-down’ strategies taken by communities of all sizes to develop an integrated support system at end-of-life that focusses on the twin concerns of quality and continuity of care. Unlike most professional systems, including the use of volunteers from within a health service, compassionate communities employ the practices of participatory civic action. This means teams of leaders (compassionate cities) or ordinary members of neighbourhoods (compassionate communities) come together to identify common problems and solutions for promoting health and wellbeing, as well as tackling the co-morbidities of dying, caregiving and bereavement.

Practice examples of both compassionate cities and compassionate communities (16) exist across multiple continents (17). Large towns and cities have developed policies and practices of support among businesses, schools, workplaces, local governments, faith groups, and for local prisons or homeless populations. Small towns and villages have developed compassionate communities across neighbourhood networks. Civic partnerships have formed in combination with primary care and social care services. Volunteers, perhaps more accurately described as activated citizens, drawn from local groups by local groups form part of the array of care supporting people undergoing experiences of death, dying, loss and care giving. In the context of public health palliative care, bereavement is included in social initiatives that start before someone has died. The continuity of relationships extends into bereavement, making use of social supports throughout the journey of bereavement. Population-based approaches are key, so that individuals who may not fit neatly into criteria of service delivery are not left uncared for. Care at end of life is everyone’s business and is greatly enhanced when palliative care services can work in harmony with and respect community action (18). Initiating compassionate cities and communities start from a variety of places, both from institutions working in partnership with communities and communities themselves. In the UK, public health leadership can sometimes come from hospices or palliative care services, but also from social care, primary care, and local government sectors. In other parts of the world, in Taiwan for example, many of these kinds of initiatives have been led by the hospital sector. In all cases, with more or less success, the goals have been civic independence and sustainability of these initiatives, whatever and whoever leads them initially.

Bereavement is an experience that carries the burden of morbidity and mortality (19), and bereavement is only one source for grief. A focus on bereavement artificially places the emphasis on survivors and ignores the response to loss by those living with dying. Finally, grief—as a response to any loss—has public health ramifications for all other areas of health and social care—from delinquency, drug & alcohol use, and school refusal to mother’s and children’s health, mental health, or social withdrawal and loneliness (20,21). Grief is naturally everywhere, but if unsupported and un or under-recognised, is pernicious. Therefore, like health care, bereavement care is everyone’s responsibility. It is not solely and simply a matter for paid or voluntary direct service providers.

Loss and bereavement as public health priorities

There is a rich body of theoretical work pertaining to bereavement within existing literature, ranging from the goal of closure to the acknowledgement of continuing bonds (22) and the importance of social networks before and after bereavement (11,23). Several approaches that have influenced the way grief and bereavement are conceptualised, are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1

| Theoretical approach | Author/s |

|---|---|

| Psychoanalytic theory | Freud (24) |

| Grief in response to an acute event | Lindeman (25) |

| Stages of dying | Kubler-Ross (26) |

| Attachment theory | Bowlby (27) |

| Grief in response to major life transition | Parkes (28), Parkes and Weiss (29) |

| Two-track model of bereavement | Rubin (30) |

| Task-Based Model | Worden and Winokuer (31) |

| Grief in response to stressful life event | Stroebe and Stroebe (32) |

| Continuing bonds | Klass et al. (33) |

| Dual process theory | Stroebe and Schut (34) |

| Meaning-making | Neimeyer (35) |

| Trajectories through bereavement | Bonanno et al. (36) |

| Public health/health promotion | Aoun et al. (11); Aoun et al. (37) |

Current professional models are based on psychological models which lack social context. More recent models have incorporated public health. Studies that have focused on the value and importance of social/public health models of bereavement support are highlighted in this section.

Phyliss Silverman’s renown ‘widow-to-widow’ program (38) communicated the experiences of widows who have found comfort and continuity in mutual-help and community support programs. The work linked theory and practice perspectives through case illustrations and challenged the professional monopoly of bereavement care. The strength, support, and friendship found among one’s peers can be crucial to the meaning making and transformative processes of bereavement. Therefore, the mutual-help approach offered a fundamental paradigm shift from the treatment of bereavement to a focus on growth and development through an intimate sharing of wisdom, tears, laughter, and experience. Through a deeper understanding of widowhood and how the bereaved can help one another, this work has empowered the bereaved to move through the grieving process with the support of their peers.

Dennis Klass and colleagues’ ground-breaking work (39,40) clarified our thinking on how bonds function in individual bereavement and argued that the hypothesis of ‘continuing bonds’ either helping or hindering bereavement adjustment was too simple to account for the evidence. The dominant model that pathological bereavement has been defined in terms of holding on to the deceased has been replaced by the thinking that healthy resolution of bereavement enables one to maintain a continuing bond with the deceased. The bonds with the dead play a major role in social solidarity and identity in families, tribes, ethnic groups, or nations. Therefore, Klass and colleagues argued the importance of the social and communal nature of continuing bonds where cultural and political narratives are woven into individual bereavement narratives. If we do not include community, cultural, and political narratives in our understanding of continuing bonds, we are in danger of building bereavement theory that applies to only a small section of a population at any one time period.

Tony Walter’s critique of the therapeutic monopoly of bereavement ideas is another milestone in cementing the importance of social models for bereavement support (41). He investigated how key factors such as money, communication technologies, economic, the family, religion, and war, interact in complex ways to shape people’s experiences of dying and bereavement. Walter challenged the bereavement model of moving on and living without the deceased and the focus on just feelings, a model based on the clinical wisdom of bereavement counselling. He suggested a more sociological model based on the construction of a durable biography that enables the living to integrate the memory of the dead into their ongoing lives and having conversations with others who knew the deceased. This allows the bereaved to continually re-create their own identity.

Several studies showed how social approaches to bereavement care have been effective in disasters, other traumatic circumstances, or major life transitions. Raphael and Hopkins (42) and Pollock (43) and Parkes (44,45) discussed the factors that played a role in successful recovery. One important factor relates to the mobilization of mutual support resources in the neighbourhood and community as these can provide effective help for some people who are attempting to cope with bereavement-associated problems. Social support plays an important role in grieving and influences the severity of bereavement, with those receiving social support less likely to experience pathological reactions (46) and social isolation associated with poorer bereavement outcomes (47).

All these studies are forerunners of today’s ‘public health model for bereavement support’, which is based on a population-based survey of bereaved people in Australia (11).

The model offers a foundation for determining the types of bereavement services and supports offered, depending on an individual’s needs and risk factors. These can be divided into three groups (Figure 1): typically, the low-risk group (about 60%) has the support they need already in place in their informal social networks. The moderate-risk group (about 30%) need some additional support from the wider community, including general support from various professionals, while the high-risk group (about 10%) typically need support from mental health professionals.

The findings endorsed social models of bereavement care that fit within a public health approach rather than relying solely on professional care. The recent emphasis on counselling as a normative response causes many people to feel that, rather than looking first to their own resources, they need to look for professional help (48). Bereavement is understood as a problem to be solved rather than an experience to be engaged (48). But professional help in the form of counselling, vital though it may be in some instances, should not be the first-place support is sought. Formal care should complement the so-called ‘informal care’, not the other way around (23).

As exemplified by Compassionate Communities policies and practices, establishing collaboration between community networks and professional services is vital for effective and sustainable bereavement care. This body of work has provided empirical evidence for the need to strengthen the compassionate communities approach, not only for end-of-life care for dying patients but also along the continuum of bereavement support (49).

In this brief review, what was considered marginal from the forerunners’ work has now become increasingly central as per the recent bereavement care policies adopted in several countries. The UK has produced a policy guide to commissioning services (12), based on the ideas of Figure 1, and Care After Caring document (50). In Ireland, replicated research triggered the development of standards for bereavement care which provided a framework for services, providing guidance on level of service provision, associated staff competencies and training needs. Their report ‘Enhancing Adult Bereavement Care across Ireland’ endorsed the ‘Pyramid Model’ (based on Figure 1) as a way forward for a national framework to shape bereavement care policy, planning and service delivery (51). At the European level, the research has informed the work of the bereavement care Taskforce of the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) to develop best practice guidelines (52). The taskforce reported that the public health framework offered a structure within which bereavement support should be considered, designed and operationalised (in palliative care and elsewhere). More recently in Australia, Palliative Care Australia produced a position statement on palliative and COVID-19 with emphasis on, bereavement and mental health encompassing the public health model for bereavement support (53).

Reimagining bereavement care

The underlying principle for reimagining support for bereavement is recognising that loss happens in the context of culture and community, which acts as the mainstay of support. The cultural context is local in nature and present the world over. Professional practice and service delivery, as recognised in the action points of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (2) needs to be reoriented to ensure that community action supporting loss is strengthened rather than weakened. Current models of bereavement support are founded on either the direct interaction of those suffering from bereavement and professionals, or the supervision of bereavement volunteers (54). We propose the redesign of the professional role. Far greater interaction is needed between professionals and the multiple sources of community support for bereavement. Sequencing of this interaction is a fundamental principle. The support offered by the care, kindness, and love of people around us is needed by everyone and is the ground of bereavement support. Professional support of any kind needs to be contextualised within social context (55).

In addition, there are many sources of bereavement support that would benefit from professional bereavement cooperation. Alliances are needed between the wide variety of places where bereavement is commonly found outside of professional boundaries. These include indigenous communities, veterinary surgeons, community-based organisations such as Men’s and Women’s Sheds, addiction support groups and meeting places such as those set up by Camerados public living rooms and many others. Education both for professionals and the public, is needed, not just to increase knowledge of how to support people undergoing the experiences of loss, but also to emphasise a social model of bereavement support. This provides an alternative to assumptions that the only valuable model of bereavement support is that of the professional. Instead, knowledge of the importance of the social model of support means that these social sources are recognised as being of primary importance.

No single solution, applied at a local or national level, can be applied that would provide population-based bereavement support for everyone. Whilst there are common themes, the experiences of bereavement and loss are unique to each person, and unique to each community. This means that a variety of different ways in which communities can support those experiencing bereavement will be needed. Listed below are suggestions of the type of health promotion initiatives:

- Bereavement cafes preferably close to every primary care team.

- Primary care teams ensure that every person who suffers from bereavement and loss is offered the opportunity to join these cafes—assessment of social relationships should be a routine part of medical care and is especially important in the context of bereavement and loss.

- Information about community sources of bereavement support readily available at local level to the public and professionals alike.

- Grief and loss policies developed at a local level for workplaces, educational institutions, local government, etc.

- Professional teams involved in end-of-life care link directly to community sources of community based-bereavement support, including within their own institutions for staff affected by loss (already established in some places, working well and critical in the pandemic response—for example the Public Living Rooms in hospitals supported by Camerados).

- Compassionate city charter implementation.

- Grief festivals, e.g., Day of the Dead, Good Grief Festival, Good Life, Absent Friends Festival, etc.

- Public education/death and grief literacy, e.g., Dying To Know Day.

- Information packs of local sources of grief support for those who are bereaved.

- The role of ritual, particularly in context of diversity.

- Faith leaders for bereavement support.

- Funeral Directors, crematoria as a source of bereavement support (56,57).

Bereavement care professionals can participate in the important task of integrating with civic participation. This necessitates participating in the development of community- and institution- based initiatives. To enable this to happen, professional services will have to develop knowledge of the wide variety of different forms of bereavement support in their areas of work. They can help to develop, support and link to these community sources rather than providing professional services. Examples include bereavement and loss policies in educational institutions and businesses, participating in festivals and supporting the many different places bereavement support is given by providing education on death literacy.

Finally, bereavement care is often framed in the context of a post death reaction to loss. However, the relationships developed through a group of people caring for someone with a terminal illness continue into bereavement. The support shown to each other during the period of caring, including the person with the illness, is fundamental to mitigating some of the more severe impacts of loss. Thus, palliative care services have an important role to play in helping to enhance the naturally occurring networks of support (58). Likewise, civic and community participation, whether starting initiatives or supporting ongoing ones, should be a routine part of both palliative care and professional bereavement services. In addition to providing services, the roles of participation and facilitation should be seen as key core components of the array of activities of professional care.

It is worth noting that the cited work is from Anglo-Saxon countries, as this paper aimed at professional bereavement services and emphasized the need for community supports. Many cultures around the world, particularly indigenous ones, have retained their culture and supports around grief and loss, and as such, they do not need to be told what they already know. It is important that their community strengths remain and are celebrated and that professional services recognize and support this.

Conclusions

A public health approach to bereavement care exposes the inadequacy of policy that focuses exclusively upon the provision of professional services, whether this is through state funding or charitable sector. The danger of professional domination of bereavement and loss is marginalisation that ignores the contribution of the community. The concern of public health is health for all, which involves attending to the complex systems of care that form within communities. Effective and sustainable care requires collaboration between formal services and informal approaches to care, often mediated by third sector organizations that represent the concerns of specific groups of caregivers. It also requires a sense of connection and mutual responsibility within communities—a stance inherent to compassionate communities—preferably fostered by leadership that strives to unite rather than divide. Population health and a nation’s political climate are intrinsically connected, as the pandemic has shown (59).

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-24/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-24/coif). AK serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Palliative Medicine from February 2022 to January 2024. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- McKnight JL. John Deere and the Bereavement Counsellor. People, Land, and Community 1997:168-77.

- WHO. The Ottawa charter for health promotion: first international conference on health promotion, Ottawa, 21 November 1986. Geneva: WHO, 1986.

- Strange JM. Death, grief and poverty in Britain, 1870–1914: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

- The Loss of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow Into Depressive Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1764-5. [PubMed]

- Granek L. Mourning matters: Women and the medicalization of grief. In: McHugh MC, Chrisler JC, Editors. The wrong prescription for women: How medicine and media create a "need" for treatments, drugs, and surgery 2015:257-75.

- Stroebe W, Schut H, Stroebe MS. Grief work, disclosure and counseling: do they help the bereaved? Clin Psychol Rev 2005;25:395-414. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer RA. Grief counselling and therapy: the case for humility. Bereavement Care 2010;29:4-7. [Crossref]

- Kellehear A. The Compassionate City Charter. Abingdon: Routledge; 2015 2016.

- Horsfall D. Developing compassionate communities in Australia through collective caregiving: a qualitative study exploring network-centred care and the role of the end of life sector. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:S42-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horsfall D, Leonard R, Noonan K, et al. Working together–apart: exploring the relationships between formal and informal care networks for people dying at home. Progress in Palliative Care 2013;21:331-6. [Crossref]

- Aoun SM, Breen LJ, Howting DA, et al. Who needs bereavement support? A population based survey of bereavement risk and support need. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Penny A, Relf M. A guide to commissioning bereavement services in england. London: National Bereavement Alliance, 2017.

- Riley SG, Pettus KI, Abel J. The buddy group - peer support for the bereaved. London J Prim Care (Abingdon) 2018;10:68-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kellehear A. A social history of dying. Death and dying, a reader. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2007:61-84.

- van der Kolk B, Sky L. The body keeps the score. UK: Penguin; 2014.

- Patel M, Noonan K. Community development. Oxford Textbook of Public Health Palliative Care 2022:107.

- Wilson G, Molina EH, Flores SL, et al. Compassionate cities. Oxford Textbook of Public Health Palliative Care 2022:117.

- Abel J, Kellehear A, Karapliagou A. Palliative care-the new essentials. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:S3-S14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fagundes CP, Wu EL. Matters of the heart: Grief, morbidity, and mortality. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2020;29:235-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Connor MF. Grief: A Brief History of Research on How Body, Mind, and Brain Adapt. Psychosom Med 2019;81:731-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zisook S, Iglewicz A, Avanzino J, et al. Bereavement: course, consequences, and care. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014;16:482. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corless IB, Limbo R, Bousso RS, et al. Languages of Grief: a model for understanding the expressions of the bereaved. Health Psychol Behav Med 2014;2:132-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rumbold B, Aoun S. An assets-based approach to bereavement care. Bereavement Care 2015;34:99-102. [Crossref]

- Freud S. Mourning and Melancholia. In: Strachey J, editor. The complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. London, UK: Hogarth Press; 1957.

- Lindemann E. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. 1944. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:155-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan Company; 1969.

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Institute of P-a, editor. London: Hogarth Press: Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1969.

- Parkes CM. The first year of bereavement. A longitudinal study of the reaction of London widows to the death of their husbands. Psychiatry 1970;33:444-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parkes CM, Weiss RS. Recovery from bereavement. Weiss RS, editor. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

- Rubin S. A two-track model of bereavement: theory and application in research. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1981;51:101-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Worden JW, Winokuer HR. A task-based approach for counseling the bereaved. Grief and Bereavement in Contemporary Society: Routledge, 2021:57-67.

- Stroebe W, Stroebe M. Bereavement and health: The psychological and physical consequences of partner loss. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

- Klass D, Silverman PR, Nickman SL. Continuing bonds: new understandings of grief. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis, 1996.

- Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud 1999;23:197-224. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer R. Meaning reconstruction and the experience of loss. Washington: American Psychological Association, 2001.

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Lehman DR, et al. Resilience to loss and chronic grief: a prospective study from preloss to 18-months postloss. J Pers Soc Psychol 2002;83:1150-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoun SM, Breen LJ, O'Connor M, et al. A public health approach to bereavement support services in palliative care. Aust N Z J Public Health 2012;36:14-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silverman PR. Widow to widow: How the bereaved help one another: Routledge; 2004.

- Klass D. Continuing conversation about continuing bonds. Death Stud 2006;30:843-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klass D, Silverman PR, Nickman S. Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. Taylor & Francis, 2014.

- Walter T. A new model of grief: Bereavement and biography. Mortality 1996;1:7-25. [Crossref]

- Raphael B, Hopkins Y. The Anatomy of bereavement: Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind. Tertiary Resource/Production Service, 1992.

- Brink YL. Recovery from Bereavement. Colin Murray Parkes and Robert S. Weiss. New York: Basic; 1983:329.

- Parkes CM. Bereavement. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 1988;18:365-77. [Crossref]

- Parkes CM. Bereavement as a psychosocial transition: Processes of adaptation to change. Journal of Social Issues 1988;44:53-65. [Crossref]

- Appel D, Papaikonomou M. Narratives on death and bereavement from three South African cultures: an exploratory study. Journal of Psychology in Africa 2013;23:453-8. [Crossref]

- Selman LE, Farnell D, Longo M, et al. Risk factors associated with poorer experiences of end-of-life care and challenges in early bereavement: Results of a national online survey of people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med 2022;36:717-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rumbold B, Aoun S. Bereavement and palliative care: A public health perspective. Progress in Palliative Care 2014;22:131-5. [Crossref]

- Aoun SM, Breen LJ, White I, et al. What sources of bereavement support are perceived helpful by bereaved people and why? Empirical evidence for the compassionate communities approach. Palliat Med 2018;32:1378-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Penny A. P-245 Care after caring: supporting family carers facing and following bereavement. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2019.

- Mc Loughlin K. Enhancing adult bereavement care across Ireland: a study. Report, The Irish Hospice Foundation, Dublin. 2018.

- Guldin M-B, Murphy I, Keegan O, et al. Bereavement care provision in Europe: a survey by the EAPC Bereavement Care Taskforce. Journal of Palliative Care 2015;22:185-9.

- Palliative Care Australia. Palliative Care and COVID-19: Grief, Bereavement and Mental Health 2020 [9/12/2022]. Available online: https://palliativecare.org.au/statement/palliative-care-and-covid-19-grief-bereavement-and-mental-health-2/

- Harrop E, Morgan F, Longo M, et al. The impacts and effectiveness of support for people bereaved through advanced illness: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Palliat Med 2020;34:871-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoun S. Supporting the bereaved is everyone’s business [Internet]. EAPC, editor. EAPC Blog2022. [cited 2023 28/3/2023]. Available online: https://eapcnet.wordpress.com/2022/07/18/supporting-the-bereaved-is-everyones-business/

- Aoun SM, Lowe J, Christian KM, et al. Is there a role for the funeral service provider in bereavement support within the context of compassionate communities? Death Stud 2019;43:619-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lowe J, Rumbold B, Aoun SM. Memorialization Practices Are Changing: An Industry Perspective on Improving Service Outcomes for the Bereaved. Omega (Westport) 2021;84:69-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoun SM, Rumbold B, Howting D, et al. Bereavement support for family caregivers: The gap between guidelines and practice in palliative care. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184750. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoun S, Rumbold B. In: Abel J, Kellehear A. Oxford textbook of public health palliative care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2022.