Is the French palliative care policy effective everywhere? Geographic variation in changes in inpatient death rates among older patients in France, 2010–2013

Introduction

The World Health Organization has identified improving care at the end-of-life as a global health priority, with improved access to palliative care as a mechanism for doing so (1). High inpatient death rates may reflect overuse of healthcare resources among patients for whom end-of-life care might be improved; and, in the mid-2000s, France has a relatively high inpatient death rate (2). Over the past decade, French policymakers have taken steps to improve care at the end-of-life. Actions have included passing a “Patient’s Rights and End-of-life Care” Act in 2005 that clarified end-of-life medical practice in France by authorizing withholding or withdrawal of treatments when appropriate (3), implementing a national 4-year plan to develop home care for end-of life patients in 2008 (4), establishing the “Observatoire National de la Fin de Vie” in 2010 (5), and taking steps to encourage patients with cancer and neurological diseases to die at home, instead of in the hospital, including changing reimbursement to discourage the use of inpatient palliative care beds, transitioning palliative care efforts to the outpatient setting, and establishing palliative care networks that coordinate home care for these patients (6).

We wondered whether these efforts to improve access to palliative care were effective at reducing the proportion of patients who die in the hospital. We reasoned that, if they were, inpatient death rates for older patients admitted with cancer or neurological diseases would decline, over time, relative to those for patients admitted for other reasons. Therefore, we examined a retrospective observation study of the rates of inpatient deaths for patients admitted with cancer diagnoses, neurological disease diagnoses, and non-cancer non-neurological disease diagnoses between 2010 and 2013.

Methods

From the Agence Technique de l’Information sur l’Hospitalisation, we obtained individual case-level data on all medical, surgical, and obstetrical discharges from all hospitals in mainland France for 2009 through 2013. Those data include the patient’s age, the primary ICD-10 admission diagnosis, the groupes homogènes de malades (GHM) code (a diagnosis related group-like code), and the mode of discharge (including death).

We sought to examine the impact of these policy changes on patients aged 65 and older, because they had a disproportionately high number of inpatient deaths (1,034,820 of 1,363,820, or 75.9%) relative to the incidence of their admissions for cancer (11,043,400 of 23,263,126, or 47.5%), neurological diseases (1,249,852 of 3,814,873, or 32.8%), or non-cancer non-neurological diseases (30,761,044 of 85,239,965, or 36.1%) during the study period. Reasoning that patients who were admitted for surgical interventions were not near the end-of-life, we further limited our analysis to patients who were not admitted for a surgical reason [those patients whose GHM code did not include the letter “C” in the third position (7), representing 34,308,609 (79.7%) of the 43,054,296 admissions among patients aged 65 and older between 2010 and 2013].

Because demographics vary geographically in France (8-10), Dartmouth Atlas Project (11) methods to calculate age- and sex-adjusted admission rates for 96 geographically-defined departments in mainland France. For each year, we obtained age- and sex-specific department-level population estimates from the French census (12). We analyzed three categories of admission: cancer admissions [non-surgical admission with a primary diagnosis of cancer (ICD-10 diagnosis beginning with “C”)]; neurological disease admissions [non-surgical admission with a primary diagnosis of a neurological disorder (ICD-10 diagnosis beginning with “G”)]; and non-cancer non-neurological disease admissions (non-surgical admissions without a primary diagnosis of cancer or a neurological disease). We identified inpatient deaths within each type of admission from the MODE_SORTEE variable (where “9” indicates inpatient death).

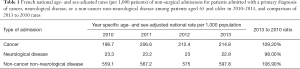

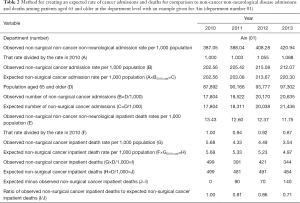

The age- and sex-adjusted rates of admission for the 3 different categories we examined changed over the study time period (Table 1). To account for secular changes, we used year- and department-specific age- and sex-adjusted inpatient death rates for non-cancer non-neurological disease admissions to model the expected number of inpatient admissions for patients with cancer or neurological diseases, had they changed at the same rate as non-cancer non-neurological disease admissions did. We then applied inpatient death rates for cancer and neurological disease-related admissions to the expected number of admissions to calculate the expected number of age- and sex-adjusted inpatient deaths for these admission types. Finally, so that we could identify geographic differences, we determined whether and how much the observed number of age- and sex-adjusted inpatient deaths differed from the expected number, at the department level. The process that we used is demonstrated in Table 2.

Full table

Full table

The study and its use of anonymized data was approved by the French National Union of Regional Health Observatories (Fédération Nationale des Observatoires Régionaux de la Santé) and the French IRB (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés, National Committee for Data Files and Individual Liberties) (CNIL authorization number 1180745).

Results

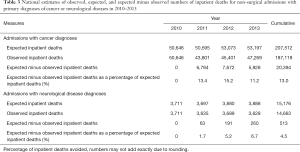

Over the study period, our model predicted that, had non-surgical cancer diagnosis admission rates tracked those of non-surgical non-cancer and non-neurological admission rates, patients admitted with a cancer diagnosis would have been expected to experience 207,512 inpatient deaths; however, 187,118 inpatient deaths were observed, which was 20,394 (13.0%) fewer than expected (Table 3). The model also predicted that patients admitted with a primary neurological disease diagnosis would have been expected to experience 15,176 inpatient deaths; however, 14,663 inpatient deaths were observed, which was 513 (4.5%) fewer than expected.

Full table

Observed-to-expected inpatient deaths fell more dramatically and more consistently for patients admitted with cancer diagnoses than for patients admitted with neurological diseases (Figure 1). Seemingly, observed-to-expected ratios fell the least (or even rose) in departments that were on the periphery of the French mainland when compared to departments in the French mainland’s center.

Discussion

Principal findings

In light of recent efforts to reduce inpatient deaths among patients with cancer and neurological disease diagnoses in France, we examined changes in the ratio of actual to expected inpatient deaths for such patients who were aged 65 and older and admitted for non-surgical reasons between 2010 and 2013. We found that observed inpatient deaths were below expected inpatient deaths for both types of admissions, considerably so for patients admitted with a cancer diagnosis.

These findings suggest that policies designed to emphasize community-based palliative care and reduce inpatient deaths among such patients have been effective. Indeed, those policies seem to have freed up substantial resources, potentially avoiding nearly 21,000 admissions in which the patient might have been expected to die over a 3-year period.

Nonetheless, we found performance differences at the department level across France; while some departments demonstrated substantial reductions in the observed-to-expected number of inpatient deaths, other departments had substantial increases in that ratio. Reductions were more consistent across France when inpatient deaths among non-surgical admissions with primary cancer diagnoses. The second French National Cancer Plan, enacted between 2009 and 2013, that was intended to improve coordination between palliative care and cancer professionals’ health networks and implemented a personal care plan for every cancer patient, could explain our findings that the greatest effects were among cancer patients (13).

Strengths and weaknesses

Our study has several limitations. First, like all studies that use administrative databases, our study assumes that coding is correct. To the extent data are miscoded, our findings are flawed. However, the general consistency of findings across years suggests that coding is consistent. Second, we did not have access to data that might explain the demand for healthcare services, such as underlying rates of year and department-specific cancer or neurological disease incidence or prevalence. Such data might help explain changes in admissions for the conditions we studied. Third, we did not have direct access about palliative care provided in the community. While we infer that community-based palliative care is the driver of changes in inpatient deaths, we cannot prove that.

However, the strengths of our study included our ability to study all relevant admissions in mainland France for 4 years, to correct for underling changes in admission practices during the time period examined, and to conduct small area variation analyses that can identify specific areas for improvement.

Implications

Our findings suggest that efforts to redeploy palliative care into the community have been effective. However, our findings also suggest that some departments may need help in achieving optimal performance levels. Policymakers might consider partnering teams from departments that demonstrated outstanding performance with teams from departments that appeared to have less effective results in order to accelerate change.

Conclusions

In France, efforts to reduce inpatient death rates among patients with cancer or neurological disease diagnoses appear to be effective. However, the effectiveness of those efforts varies geographically, suggesting that targeted efforts to improve lower performing departments may generate substantial performance improvements.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Weeks was funded by a Fulbright-Tocqueville grant through the Franco-American Commission for Educational Exchange and by the Institute of Advanced Studies at Aix-Marseille University.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study and its use of anonymized data was approved by the French National Union of Regional Health Observatories (Fédération Nationale des Observatoires Régionaux de la Santé) and the French IRB (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés, National Committee for Data Files and Individual Liberties) (CNIL authorization number 1180745).

References

- Davies E, Higginson IJ. Better Palliative Care for Older People. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization; 2004 [cited 2016 June 2]. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/98235/E82933.pdf

- Broad JB, Gott M, Kim H, et al. Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. Int J Public Health 2013;58:257-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baumann A, Audibert G, Claudot F, et al. Ethics review: end of life legislation--the French model. Crit Care 2009;13:204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Programme de développement des soins palliatifs.: Ministère des Affaires Sociales et de la Santé, Paris 2008 [updated le 13 Juin, 2008; cited 2016 June 2]. Available online: http://social-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Programme_de_developpement_des_soins_palliatifs_2008_2012.pdf

- Observatoire National de la Fin de Vie [cited 2016 May 15]. Available online: http://www.onfv.org/

- Circulaire 21/20 du 04 Février 2003 relative à application de la circulaire DAR n°5-2000 du 22 Mars 2000. Paris: L'Assurance Maladie des Salariés-Sécurité Sociale, Caisse Nationale; 2003 [cited 2016 June 2]. Available online: http://social-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Circulaire_de_la_CNAM_noCIR-21-2003_en_date_du_4_fevrier_2003_relative_au_financement_du_dispositif_de_maintien_a_domicile_dans_le_cadre_des_soins_palliatifs.pdf

- Ministère des Affaires sociales et de la Santé. Manuel des groupes homogènes de malades. 11ème version de la classifcation, 6ème revision (11g). Version 13.11g de la fonction groupage. Volume 1: Présentation et annexes générales. Section 1.2.2. [cited 2016 May 15]. Available online: 2015http://www.atih.sante.fr/sites/default/files/public/content/2708/volume_1.pdf

- Weeks WB, Jardin M, Dufour JC, et al. Geographic variation in admissions for knee replacement, hip replacement, and hip fracture in France: evidence of supplier-induced demand in for-profit and not-for-profit hospitals. Med Care 2014;52:909-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weeks WB, Jardin M, Paraponaris A. Characteristics and patterns of elective admissions to for-profit and not-for-profit hospitals in France in 2009 and 2010. Soc Sci Med 2015;133:53-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weeks WB, Paraponaris A, Ventelou B. Geographic variation in rates of common surgical procedures in France in 2008-2010, and comparison to the US and Britain. Health Policy 2014;118:215-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care: Indirect Adjustment [cited 2016 March 8]. Available online: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/methods/indirect_adjustment.pdf

- Estimmation de la population au 1er janvier par région, dépeartment (1975-2014), sexe et âge (quinquennal, classses d'âge). Paris, France: INSEE - Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques; 2015 [cited 2016 January 14]. Available online: http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/detail.asp?reg_id=99&ref_id=estim-pop

- Plan cancer, 2009-2013. Paris: Institut National du Cancer; 2013 [cited 2016 June 2]. Available online: http://social-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Synthese_plan_cancer_2009_2013.pdf