Sedation indicated?—rethinking existential suffering: a narrative review

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing, end them? To die: to sleep.

[William Shakespeare: Hamlet (1)]

Introduction

If treatment to relieve suffering at the end of life fails, palliative sedation therapy1 is accepted as a valid option (2-8), which is appropriate for physical suffering. In this article we question the adequacy of “treatment” in a medical sense for persons suffering existentially.

Suffering has an appellative and normative character (9). Frankl describes suffering as being primarily experienced as meaningless by those who suffer (10). This gives rise to an intense desire to comprehensively alleviate suffering, either by making it vanish completely or at least covering it.

Patients report a more or less pronounced form of existential suffering (ES), which can fluctuate or be constant over time (11). The facets of existential concerns described are manifold (Appendix 1). Depending on the questions in studies or the underlying concepts, the prevalence of ES ranges between 13–18% (12), 24–35% (13), 30.5% in mean (14) and over one third (15), with significantly higher or lower numbers of cases reported in other studies.

The capacity to suffer, however, is part of the human condition (9). Other capacities rooted in the human nature are negative feelings, such as pain, aversion, and fear of injury or destruction, but also positive emotions, such as joy and happiness, as well as interaction with the environment or other people, including love (16). The central drive of modernity is the concept of making the world available, governable and controllable. But the human condition, and thus its negatively perceived capacities, represent an uncontrollable fact (17). Due to this perception, pain and suffering are a provocation.

Alleviating suffering

The relief of pain and suffering caused by maladies was identified as a main goal of medicine by Cassell (18) and in the Hastings Centre Report (19). The order to alleviate suffering is strengthened in the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of palliative care (20) and creates a distinct pressure for professional palliative caregivers to act. Not all kinds of suffering should be an explicit object of medical interventions (21), as evidenced by experiences in which ES is mostly unresponsive to psychopharmaceuticals (22).

Taboo of suffering

The perceived imperative to alleviate all suffering can result in a taboo of suffering and adverse consequences (23). Professional caregivers may perceive the following aspects: the above-mentioned pressure to act, ES that cannot be comprehensively alleviated by usual (medical) means (22), and the contagious nature of suffering due to an identification with the suffering person (24). These experiences could promote the intention to make suffering invisible, to “treat it away”, by palliative sedation therapy, more precisely by continuous deep sedation until death. The described provocation by suffering and pain, by the uncontrollable human condition, leads to the urge to banish these negative experiences completely in modern control- and autonomy-addicted society. Ultimately, this imperative to avoid suffering at all costs opens the door to assisted dying2, to abolish suffering by abolishing the sufferers (16), and in the extreme elimination of suffering by eliminating the sufferers (23).

Transforming suffering

Individuals can transform or alleviate suffering by adjusting their meaningful values (25). A central issue of this review is how existentially suffering people can be accompanied on a path to a new quality of life without being burdened by the taboo of suffering.

Central task of palliative care

Supporting this process is a core task of professional palliative caregivers. Key obstacles to this assistance are founded in the hitherto inconsistent description and definition of ES in international medical literature (22,26,27), a lack of knowledge among professional caregivers (28) and the contagious nature of suffering by empathic distress (24,29).

For almost 30 years, various research groups have extensively studied existential concerns and described them in quite similar ways using different terminologies (30). Two of the best known and most effective constructs are Kissane’s comprehensive elaborated model, which speaks primarily of demoralization (12,24,31,32), and Chochinov’s dignity-based model (33-36). The known constructs are summarized into a taxonomy of existential concerns (37). However, these concepts of ES did not reach the basic health care system, and thus the patients, because the landscape of concepts is perceived to be diffuse and not congruent.

Existential Analysis3 offers the most coherent explanations of the underlying processes of ES (38).

Core question

Considering the tension between the appellative character of suffering and the uncontrollability of the human condition, we will try to answer the following question. Which measures are adequate: alleviate suffering, eliminate it completely, or perhaps enable existential sufferers to regain a new quality of life?

In this article we first present a refined concept of ES based on Existential Analysis. Second, we describe the needs of patients, informal and professional caregivers burdened by ES and resulting helpful interventions. Third, we discuss palliative sedation therapy for individuals with ES. We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-474/rc).

Methods

A narrative review was performed after PubMed search using key terms related to ES and sedation, covering the period from 1950 to April 2023, additionally a selective search in specialist literature on Existential Analysis. Relevant articles were further processed by reverse and forward snowballing. The language of analyzed publications was restricted to English and German. Further details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | April 12th 2023 |

| Databases and other sources searched | PubMed, specialist literature on Existential Analysis |

| Search terms used (please see Table S1 for detailed information) | Unbearable existential suffering, palliative sedation, guidelines |

| Timeframe | 1950–April 2023 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion: clinical trials, randomised and cohort studies—both retro-and prospective, case reports, reviews (systematic and narrative), meta-analyses |

| Exclusion: psychiatric diseases, dementia, children, basic- and animal research | |

| Selection process | The search strategy was developed and screening was performed by C.G., followed by reverse and forward snowballing. The references were checked by the co-authors and missing ones completed; in case of discrepancies, consensus was reached through discussion |

Results

The refined concept of ES

The underlying process of ES

Suffering potentially alienates a person’s mood by experiencing that suffering prevents her or him from realizing the own primal values, at least by experiencing loss of meaning and purpose in life. Suffering-moods, so-called by Svenaeus (25), are moods in which a suffering person lives. They invade the entire existence and present the world and life in an alienated way. Suffering-moods are mental and have an intense and painful nature. In Buddhism, this process is called “pain of pain” or “suffering upon suffering” (39,40). Existential pain is mostly used as a metaphor for suffering (41). Another metaphor for suffering is “pain of the soul” (42), a metaphor that enables patients, relatives and health care professionals to empathize with suffering situations.

Thus, we need to understand the fundamental suffering-moods leading to the factors described by patients (Appendix 1), which show the suffering person’s estranged perception of the world. These fundamental processes are explained by Existential Analysis.

Frankl considered the search for meaning to be the deepest motivation of human beings (43). Längle has developed the concept of modern Existential Analysis (38).

Three additional existential motivations have been identified that precede the motivation for meaning. According to this present understanding, human beings are only and truly free to find meaning in a given situation, if the four fundamental conditions of existence (Table 2) are fulfilled (44,45).

Table 2

| (I) Relationship to the world and its conditions, acceptance of reality—fundamental question of existence: I am—but can I be (a whole person)? Can I accept my situation in the world? Do I have the necessary space, protection and support? |

| Roots of suffering (examples): loss of hold, loss of ground, feeling of powerlessness |

| (II) Relationship to life and its value—fundamental question of life: I am alive—do I like this? Is my life valuable? Do I experience abundance, affection and appreciation of values? |

| Roots of suffering (examples): loss of joie de vivre, not feeling vital |

| (III) Relationship to self, identity and authenticity—fundamental question of the person: I am myself—but do I feel free to be myself? Do I experience appreciation, esteem, respect, my own worth? Is my behavior truly my own (conscience)? |

| Roots of suffering (examples): loss of self-esteem, dignity or identity; loneliness |

| (IV) Relationship to the wider context and meaning—fundamental question of existential meaning: I am here—for what good? What is there to do today to make my life part of a meaningful whole? What will outlast my life? |

| Roots of suffering (examples): my life is good for nothing; feeling of meaninglessness, pointlessness and void; feeling of living in vain |

These four valuable and vitally important conditions can also be described as life-supporting, as the foundation or basis of fulfilled existence, of being a person. These values carry the human being; they give a safe foundation for life (42).

ES, pain of the soul, suffering-moods, suffering upon suffering, develop when one’s prerequisite for a good life is lost. The person is confronted with (real or perceived) destruction of one or more of these valuable fundamental conditions of existence (25,46). ES is the perceived separation from the fundamentals of existence; even shorter: suffering is a perceived loss of existence (42). Suffering and pain jeopardize our life totally or partially and menace our love for life (46).

This metaphor of the destructed foundation of existence explains many situations of suffering. For example, patients being informed about a fatal disease describe feelings of losing ground. These patients have experiences like they are hanging over an abyss without any hold and will soon fall, which is a highly threatening situation.

Loss of meaning, the root of all misery?

Patients who suffer existentially often report a sense of meaninglessness and pointlessness, and some feel completely hopeless and paralyzed. To truly support these patients, it is necessary to analyze with the patient what underlies this experience. When questioning meaning (of life), it must be considered which of the four fundamental conditions (one or more) has been rocked. In this case, an exclusive preoccupation with the problem of meaning would obscure the actual problem, hinder processing and coming to terms with it by those affected and thus overcome suffering (46).

Finding meaning can only succeed if the suffering person observes and recognizes the fundamental conditions in which the primary perceived destruction has taken place. This allows sufferers to adapt their meaningful values to the new situation, which can transform or alleviate suffering (25).

Finding meaning in life and suffering: three categories of values

Frankl states: “We fulfill the meaning of being - we fill our existence with meaning - always by realizing values” (47). He summarized the values that enable an existential sense of meaning and thus represent the basis for a meaningful design of life in three value categories:

Experiential values: the primal beauty and uniqueness of life is realized by experiential values (48), making life meaningful. Examples include: nature, art, encounters with other people in conversation and love.

Creative values: generativity is one of the greatest sources of meaning (49). Creativity and creation enrich the world with value: creating a work, e.g., art or technology; accomplishing tasks, e.g., at work; raising children; standing up for weaker people or a belief; and a successful life’s work. Leaving a legacy is considered important in interventions (33,50-52).

Attitudinal values: by realizing attitudinal values, the individual can attune her/himself to limitations in life (10); in confrontation with fate, meaningful dealings with suffering can be achieved (48). Additionally, suffering may be transformed or at least mitigated by a person’s identifying and changing her or his core life values (25), i.e., by adjusting attitudinal values.

The distress of cancer patients may be reduced when they perceive their lives as meaningful, comprehensible and manageable (53), confirming Antonovsky’s works (54).

Existential despair, suffering without hope—the real misery

People cannot directly experience meaning in suffering (10), suffering in itself is meaningless (46).

Within the context of hope, people remain connected with their supporting values without losing sight of reality. Hope is not a defense mechanism through self-deception; therefore, real hope does not block further important steps. Hope maintains a connection with the future that gives strength and orientation, even though it cannot influence reality. Hope has meaning because it is oriented toward the future (55). The question of meaning emerges when the path into the future seems blocked. Nietzsche states: “Not the suffering itself was his problem, but that the answer was missing to the cry of the question: Why suffer?” (47). Hopelessness is an essential element of unbearable suffering (56).

Therefore, when hope is lost, when hopelessness arises, meaninglessness is also experienced (55). Then experienced ES leads to existential despair, and despair is suffering without meaning (48).

In the case of a persistent, all-encompassing sense of meaninglessness, Frankl speaks about an “existential vacuum” (10). In the context of this emptiness and despair, there is an increased risk of addiction and/or suicidal ideation because the person no longer has anything to support her or him in suffering and stress in life (57,58). Studies have confirmed that hopelessness is a strong predictor of the desire for death (59,60). In this crisis of life and suffering, the wish to hasten death or suicide represents the possibility of putting an end to this massive pressure (46).

Systematic of ES

As described above, the concepts of ES have not yet comprehensively reached the basis of palliative care. Therefore, ES is often missed or neglected (15). A major cause of this is a lack of uniformity in the definition and understanding of ES (26). Based on the considerations of Existential Analysis described above, we propose a differentiation of the terms “ES, distress and despair” (Figure 1). This more precise terminology is intended to increase safety in encounters with existentially suffering persons.

The central triad of ES

Research groups working on themes of suffering and despair over decades have observed a frequent combination with a wish to die (50,58-68).

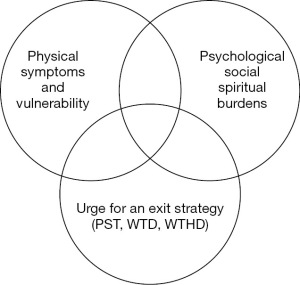

The development of multidimensional ES and the resulting urge for an exit strategy are based on complex processes. In care for existentially suffering patients, three main aspects can be observed: the triad of ES (Figure 2).

The triad was developed to quickly assess whether patients are burdened by the experience of existential distress or despair based on of a simple model in daily work. This provides short-term support, which should lead to an improvement in the quality of life of patients and relatives and relieve the burden on care teams. After recognizing ES, a more in-depth assessment should be performed. The Psycho-Existential Symptom Assessment Scale (PeSAS) is designed for this purpose (15).

Cassell states that suffering is an affliction of whole persons, not bodies (69,70). Therefore, we stress the holistic nature of this triad model. The apparent separation into physical and nonphysical stresses serves to improve understanding and clarity as well as to quickly identify symptoms that may be treated with medication. All three aspects of the triad are intertwined, they interlock and are interdependent. Den Hartogh states: “The effects of those factors are indistinguishable from the effects of illness. Effects from various sources may reinforce each other” (71). The holistic approach is explained in the “Total Pain Model” (72) and in the heuristic model (73).

Manifest depression has to be excluded before the triad is deployed. A depression must be distinguished from ES (58) and treated by medication (50). Anhedonia, the loss of ability to experience pleasure, is the dominant symptom of clinical depression, but not of ES (74-76).

Physical symptoms and vulnerability

Palliative care patients suffer from a variety of physical symptoms, up to loss of function. ES often intensifies physical symptoms (e.g., pain or nausea) and impedes their treatability, or even may trigger symptoms. Sometimes no physical causes for these symptoms can be identified and relief is hardly achievable with pharmacological measures.

Psychological, social and spiritual burdens

The facets of ES (Appendix 1) are no mental disorders near death. Depression or anxiety do not increase in the case of existential threat, but various manifestations of suffering do (77).

Urge for an exit strategy (sedation, wish to die with or without hastening death)

The two aspects of the triad mentioned above can cause massive suffering. Particularly stressful is existential despair, leading to a more or less pronounced request for an exit strategy. This exit strategy can be the wish for palliative sedation therapy, the wish to die or to hasten death (68,78,79). Two basal triggers for the wish to die or to hasten death are identified: symptom burden and lack of meaning in life (80).

As shown in a study, 18.3% of patients reported occasional and transient thoughts in this regard and 12.2% reported a serious death wish (81).

These triggers for the urge of an exit strategy also become visible in the end-of-life concerns in the Oregon Death with Dignity Act (Appendix 2) and in the mentioned Austrian study (14). Controlling the circumstances of death and maintaining independence are important triggers (62). The wish to die and will to live change over time and in intensity (82).

Another important reason for an exit strategy is to anticipate the time when suffering becomes unbearable: “Wish to hasten death as a kind of control, ‘to have an ace up one’s sleeve just in case’” (83).

Needs of patients, informal and professional caregivers burdened by ES

The contagious nature of ES and empathic distress

Kissane described the contagious nature of demoralization (24). Brain research suggests the following explanations. The same empathy-for-pain network in the brain is activated in the sufferer and the observer, and they therefore share emotions (84-86). However, if the receiver cannot distinguish between self and other’s emotion, this effect of empathy turns into empathic distress, and the observers experience themselves as being just as burdened as the suffering person (29).

The compassion-related network is located in other areas of the brain (84,87). By activating it, altruistic feelings for the suffering people arise: benevolence, kindness and warmth of heart, and a deep motivation to comfort suffering individuals.

Empathic distress, i.e., the described contagious nature of ES, is one of the main triggers of burnout, moral distress and empathy fatigue for palliative caregivers (88) and thus of a decline in the quality of care. In the Austrian-wide survey “Care of people in deep existential despair”, an increased burden on staff of palliative care teams was demonstrated by more requests for the administration of psychotropic drugs or palliative sedation therapy and a decrease in patient contact (14). Physicians with higher levels of professional burnout were more likely to choose continuous deep sedation (89). Since the results of the studies described above are associated with an impairment of the quality of life of suffering patients, these measures must also be regarded as aggression or violence in care.

The crucial question: what do existentially suffering patients and informal caregivers need?

According to the following needs of patients and relatives, we postulate our benchmark phrase for the care of existentially suffering individuals (Table 3).

Table 3

| Existential suffering is a highly individual and a nonpathological condition |

| It has a contagious nature |

Acknowledging the subjectivity and individuality of suffering: “The only way to learn, (…) whether suffering is present, is to ask the sufferer” (18). This leads to the following conclusion: the question of whether a person is suffering cannot be answered by scientific knowledge (16). Suffering, such as the conception of a good life and dying well (71), is dependent on individual thought patterns and values because every person has different predispositions and a unique, characteristic life narrative, in the continuum of patients’ (and caregivers’) perspectives of the past, the present and expectations of the future (41,56).

Focusing on patients, ES of relatives is often overlooked. Their suffering has predominantly different backgrounds than the suffering of patients (90-97).

Competent health care professionals who are able to listen reflectively: Existential sufferers need caregivers who are well versed in matters of ES and who are aware of spiritual and existential dimensions of their own lives (98). Thus, these caregivers are able to support suffering people and reflectively listen to them without being burdened by empathic distress. Reflective listening means offering a mirror by asking questions and not giving advice (99). This allows sufferers to develop attitudinal values because they have no influence on the fate for which they suffer (48). These attitudinal values facilitate a meaningful way of dealing with suffering by transforming or mitigating it (25).

The Patient Dignity Question (PDQ) asks: “What do I need to know about you as a person to give you the best care possible?” (60,100,101). A recent study demonstrated that PDQ can be used as a means of eliciting values among patients with cancer (102). Support provided by competent carers enables sufferers to reconnect with the fundamental basis of their existence and thus to find a way into the future under present circumstances.

Goals of medicine: Den Hartogh states: “The nonphysical aspects of suffering (…) are more or less appropriate responses to the actual circumstances of the patient. These circumstances often are such that it would rather be a pathological symptom not to be sad and not to suffer. Suffering, therefore, is sometimes and to some extent a condition to be respected” (103). Since ES is not a pathological condition, medicalization represents an inadequate approach. As practical experience shows, psychotropic drugs in particular are of little or no help, but their side effects can be considerable. van Hooft explains: “It becomes self-evident that the relief of suffering should be one of the goals of medicine, but that not all kinds of suffering should be the explicit object of medical interventions” (21), according to the principle of therapeutic responsiveness (104). Physicians can and should support existentially suffering patients as human beings, companions and discussion partners but not with medication.

Meaning-centered interventions are beneficial in empowering existentially suffering persons to develop their attitudinal values. Different research groups have developed validated tools: PDQ (60,100,101), Patient Dignity Inventory (PDI) (35) and dignity therapy (36); Meaning Centered Group Psychotherapy (MCGP) (105-107); Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation (SmiLE) (108,109); and Managing Cancer And Living Meaningfully (CALM) (110,111).

Palliative sedation therapy for ES?

Any medicalization in the last phase of a person’s life must be performed with comprehensive consideration of its relevance. Performing intermittent palliative sedation therapy to temporarily distance from the fateful situation can be helpful for existentially suffering patients to regain their emotional strength. Critical consideration must be given to the use of continuous deep sedation and continuous deep sedation until death, which are conducted differently in various countries, as shown in the UNBIASED study (112).

Research shows that the prevalence of palliative sedation therapy varies considerably. In physicians’ opinions, the use of continuous sedation to relieve ES was considered acceptable: in the last days of life (45–88%) and when the prognosis was at least several weeks (5–42%) (113). The indication of sedation for existential distress during the last two weeks of life in Austrian palliative care units was 32%, with a smaller, unspecified number of patients receiving intermittent sedation (114).

Based on the following facts, continuous deep sedation may pose an increased risk of harming unresponsive persons:

- Persons under continuous deep sedation are unable to communicate; thus, this procedure means the end of a person’s biographical (social) life. Existential sufferers may therefore be deprived of the only secure aid and support that caregivers can no longer provide by communicating, accompanying and giving hold to them.

- The crucial question is whether existential despair is truly mitigated by sedation or whether professional and informal caregivers only believe this (or want to believe this). None of the 14 studies in a Cochrane review measured the quality of life or well-being during sedation (115). Doubts exist regarding whether patients are aware of and can experience ES despite unconsciousness (116).

- Unresponsiveness is not equal to unawareness (117). After general anesthesia, almost 60% of patients recalled subjective experiences (118). The consequences of sensory deprivation and lack of appropriate sensory stimuli are: disturbance of orientation in space, loss of intellectual abilities, occurrence of complex hallucinations, altered body perception, and altered experience of time (119). Suffering is not a function of consciousness (21).

Medicalization of death by continuous deep sedation until death is evident. The frequency seems to be increasing in the last two decades in many countries, which means that palliative sedation therapy may have lost its “last resort” status. This is due to the increasing number of sedations for non-physical symptoms (120). In studies of end-of-life practices, 12% of all deaths were observed under continuous deep sedation until death in Belgium in 2013 (121), 17.5% in Switzerland in 2013 (122), and 18.3% in the Netherlands in 2015 (123). In the same period, the number of assisted deaths also increased.

In Belgium, doctors justify palliative sedation therapy in cases of ES on the basis of the principles of biomedical ethics, respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and, to a lesser extend, based on the principle of justice (124,125). In a repeated cross-sectional survey in 2005, 2010, and 2015 in the Netherlands, the following explanations for this increase were found, which can be attributed to societal developments: increased attention to sedation in education and society, a broader interpretation of the concept of refractoriness, and an increased need of patients and physicians to control the dying process (126). Continuous deep sedation until death can be perceived as a ‘natural’ death by medical practitioners, patients’ relatives and patients (127). The label ‘natural’ becomes a way of framing a death as ‘good’, and the term ‘medicalized’ seems to indicate a bad death. In a study among Dutch physicians, 60.7% agreed that death after continuous deep sedation until death is a ‘natural’ death (128). These physicians believe that patients under continuous deep sedation until death die from underlying diseases, and therefore, death is natural. Palliative sedation mimics a death occurring in deep sleep: one version of the good or ‘natural’ death which is popular in the developed world (129).

Concept of “good dying” and illusion of control

The concept of a good death is a significant predictor of physicians’ decisions at the end-of-life (130). Good dying has many different attributes, which are viewed differently by patients, relatives and carergivers: being seen and perceived as a person, low physical and psychological burden, preserved social relationships and spiritual/existential well-being, as well as good quality of holistic care and adequate preparation for dying (131-136).

The signum of dependence inevitably belongs to being human and is thus part of the human condition. In the sense of a one-sidedly understood concept of autonomy, of insisting on autonomous control, being dependent on the help of others experiences the increasing tendency to disregard all seriously ill life and thus the tendency to abolish frail life (137). An essential concept of modernity is an available and controllable world (17). In an integrative literature review, the influence of neoliberal social development on the conception of a good life and dying well is described. Ultimately, the neoliberal values of autonomy, freedom, choice and control become an illusion. The paradox of coexistence of control and freedom results in the obligation, almost the coercion to choose and thus a loss of freedom. At the apex of a neoliberal society, death is managed and consumed according to ‘free market’ principles. Denial of dying, which is regarded as exclusively negative and useless, apparently represents the culmination of control and autonomy (138).

Discussion

Caring for existentially suffering patients can be a major challenge, requiring a completely different approach to the proven strategies for alleviating suffering.

The human condition of being mortal and vulnerable includes the dependence on others (137) as well as the capability for suffering (9). Patients have to be seen as whole persons rather than the embodiment of their disease or disability (60,100).

To optimally accompany existentially suffering patients within this context, different needs of patients and caregivers must be understood, and appropriate framework conditions must be defined. The dogma of alleviating suffering in palliative care as well as the possibility of palliative sedation therapy require critical reflection.

- The needs of patients and their families in cases of ES are clearly outlined by the two elements of the guiding principle (Table 3).

- ES is a highly individual condition: Saunders comprehensively described the needs of people in existential distress or despair (Table 4). Existentially suffering patients need well-trained caregivers who can perceive individual situations and reflectively listen without giving advice; by doing so, they enable suffering people to develop attitudinal values described (10). Thus, meaning is found again by transforming or at least mitigating suffering by identifying and changing fundamental life values (25). The human being has the potential to evolve and restore psychosocial well-being until the last day (104). Existentially suffering patients need caregivers who are able to provide assistance and who can withstand the suffering.

- ES is a nonpathological condition: although alleviating suffering is one of the goals of medicine (18-20), medical intervention is not indicated for all forms of suffering (21). ES is nonpathological (103), and in nonpathological situations, there is no indication for the administration of psychopharmaceuticals or palliative sedation therapy. The only potential healer is the existential sufferer her/himself, medical treatment cannot achieve this.

- Needs of professional caregivers. Comprehensive challenges faced by health care professionals may result in feelings of incompetence, distancing from patients and thus poorer quality of care (14), and ultimately in burnout and leaving the profession (88). Pressure experienced by caregivers can clearly lead to the desire to perform palliative sedation therapy or assisted dying so that suffering no longer has to be witnessed.

The following challenges can be identified:- ES and spiritual pain are still poorly understood by health care professionals (28) due to a lack of consensus on the assessment, definition and treatment of ES (26,68).

- Concepts for training on the topics of suffering and existential despair are missing (139).

- The most significant challenge in everyday work arises from the appellative nature of suffering, the normative character of the concept of suffering (9) as well as the threatening downward spiral for caregivers and patients due to empathic distress, which has been verified in brain research (24,29).

- The usual drug interventions mostly fail with ES (22).

To improve the quality of care for patients and to promote the health of caregivers, a clear concept for ES is needed. The concept of Existential Analysis makes patients’ backgrounds and narratives understandable (42,44-46). The triad of ES (Figure 2) is a memorable model that fosters a multidimensional assessment of ES. Furthermore, comprehensive training courses that correspond to the recommendations in the EAPC White Paper on education in core competencies in palliative care should be organized (98). A reflection of one’s own finiteness and capacity for suffering by professional caregivers helps to support patients, to listen in a nonjudgmental way and to accompany patients on their path. Ultimately, a compassion training program is future-oriented as an antidote against empathic distress (87).

- The human condition vs. the taboo of suffering.

The capacity to suffer is part of the human condition, like joy or love, and embracing it provides decisiveness and thus a sense of freedom. Of course, this acceptance is diametrically opposed to the modern understanding of autonomy of being able to decide everything in life. This insight is the result of a longer process in life and usually cannot be achieved in the very last period of life, often marked by loss and suffering.

Alleviating suffering remains the central task of palliative care (20). Professional palliative caregivers are under pressure due to the appellative nature of suffering. This comprehension of human nature may help them to accept that ES can often be mitigated but not treated with medication. This reflection clarifies that mitigating suffering must not become the sole imperative up to the taboo of suffering. The only person who can transform suffering-moods, suffering upon suffering, is the existentially sufferer her/himself.

Therapeutic humility is recommended when accompanying existentially suffering persons, because the sufferers themselves are the only experts. Furthermore, it must be accepted that suffering cannot be fixed and sometimes resists its alleviation. In this case, helplessness must be endured together with the patient (23,60,140) (Table 4).

Table 4

| “‘Watch with me’ means, above all, just ‘be there’”, by Saunders (72) |

| “‘Watch with me’ means, still more than all our learning of skills, our attempts to understand mental suffering and loneliness and to pass on what we have learnt. It means also a great deal that cannot be understood. Those words did not mean ‘understand what is happening’ when they were first spoken. Still less did they mean ‘explain’ or ‘take away’. However much we can ease distress, however much we can help the patients to find a new meaning in what is happening, there will always be the place where we will have to stop and know that we are really helpless. (…) Even when we feel that we can do absolutely nothing, we will still have to be prepared to stay.” |

Palliative sedation therapy for unbearable and otherwise untreatable physical symptoms is clearly described, defined and uncontroversial (7), as is intermittent palliative sedation therapy to distance from existential despair and to regain emotional strength. Continuous deep sedation until death of unendurable existentially suffering patients is controversial for several reasons (5), ranging from (sometimes seemingly) imprecisely defined frameworks and regionally varying practices, the inconsistent picture of ES in the medical literature, to the inadequate training of professional caregivers, who are clearly burdened.

- Frameworks: palliative sedation therapy to alleviate otherwise intractable ES by an intended reduction in consciousness is covered by the EAPC framework (2). In the last few years, several reviews of guidelines have been published (3-6), but the guidelines can only describe a framework (141,142). Palliative care professionals should be able to operate within this frame, whereby following boundaries must not be violated. According to our benchmark phrase “ES is a highly individual and nonpathological condition”, palliative sedation therapy must be used as an exceptional last resort measure (8,143-147) in end-of-life care. When using palliative sedation therapy, the EAPC definition of palliative care that “it neither hastens nor postpones death” (148) must be respected.

The necessity of a shared worldwide definition of palliative sedation therapy to make the practice of different countries comparable in research is evident (130). Whether good guidelines alone are sufficient is questioned (149). In different countries, for historical reasons, various anthropological approaches regarding the human condition (150) and diverse concepts of good dying exist (126-136,138,149). Therefore, we do not expect that further frameworks can lead to an internationally uniform approach. The use of continuous deep sedation in countries such as the U.S., Norway or France leads to ‘mission creep’ (151), which completely contradicts the EAPC definition of palliative care. - Attributes of suffering are intractable/refractory (152) and intolerable/unbearable (56,153,154). They are prerequisites for offering palliative sedation therapy (2-7,155) and amplify the appellative character of suffering and thus empathic distress. Treating ES is limited (146,156) and mental distress may be perhaps the most intractable pain of all (157). We plead that, despite the carers’ perceived helplessness in facing a person suffering unendurably, pharmaceutical treatment is inappropriate.

- Decision-making for palliative sedation therapy: the decision to use palliative sedation therapy requires the same prerequisites as any other therapeutic measure, a physician’s indication and consent from the patient or his or her legitimate proxy (158). This process should be conducted by the multiprofessional team after discussion of all pros and cons. After comprehensive information of the patient and her or his relatives, informed consent has to be established, which is required by guidelines (5,7,8,146,147,150,159). This respect for autonomy must be preceded by an indication, considering the benefits and harms of palliative sedation therapy. For this, too, a profound and holistic understanding of existential concerns is absolutely essential.

- Harming existentially suffering patients by continuous deep sedation: the risk of harmful effects cannot be estimated, but seems to be substantially increased, especially because existential sufferers in continuous deep sedation are alone, and communicative support in ES by fellow human beings is no longer possible. Unresponsiveness is not equal to unawareness (117), and there are no data on well-being under continuous deep sedation (115). Therefore, continuous deep sedation may “result in a drug-induced ‘locked-in’ syndrome, and the patient dying in great, but unrecognized, distress” (147).

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, that existential analytic perspective of ES is published in this review for the first time in the international medical literature. An interdisciplinary expert author group analyzed the literature on the topic of ES for palliative sedation therapy.

However, a few limitations apply to this review. Only articles in English and German were included and there may be relevant articles published in other languages (e.g., French) that have not been included. In general, key statements are supported by voluminous references. The authors admit the risk of having missed valuable documents that had to be taken by accepting a selective, narrative literature review and searching in one database (PubMed) only.

Furthermore, the first international presentation of the triad of ES is included in this article. The theoretical background is taken from specialist literature on Existential Analysis and from peer-reviewed journals. Further studies are required to validate and evaluate the practicability of both in daily palliative care as well as empirical research to empower clinical practice.

Conclusions

Palliative care philosophy embraces more than medical treatment, central values are patient-centredness and culture of care. (Palliative) medicine has reliable strategies to assess and treat physical suffering. In the case of ES, however, other skills are needed. Support (and not medicalization) of persons suffering existentially is one of the core competences of palliative care professionals.

Continuous deep sedation must remain an option of last resort for two reasons: existentially suffering patients benefit exclusively from personal support of other persons and not from medicalization in end-of-life care; furthermore, the risk of harming unresponsive, existentially suffering persons through continuous deep sedation contradicts the nonmaleficence principle of biomedical ethics.

To improve the quality of care for patients and to promote the health of caregivers, extensive education and a clear concept of existential concerns are needed. The presented concept of ES makes the patients’ backgrounds and narratives understandable. The triad of ES, as a concise model, promotes a multidimensional assessment of ES.

We clearly emphasise the crucial necessity of individual accompaniment in the realm of human suffering, especially in those moments when we cannot fix anything and feel helpless. We must be prepared by knowledge, experience in communication and self-reflection. In this way, we can stand with the existentially suffering individuals through our personal, stable presence.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their special thanks to Prof. Jan Schildmann for his inspiring amendments and their sincere thanks to Susanne Pointner and Alexander Milz for the expert review of the sections on Existential Analysis. The manuscript was edited by the AME Editing Service.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by Guest Editors (Jan Gärtner and Manuel Trachsel) for the series “Ethics and Psychiatry Meet Palliative Medicine” published in Annals of Palliative Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-474/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-474/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-474/coif). The series “Ethics and Psychiatry Meet Palliative Medicine” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

1Defintion: Palliative sedation therapy is the monitored use of medications intended to induce a state of decreased or absent awareness (unconsciousness) in order to relieve the burden of otherwise intractable suffering in a manner that is ethically acceptable to the patient, family and health-care providers (2).Forms of palliative sedation therapy: Transient or respite sedation for 6–24 hours may be indicated to provide temporary relief whilst waiting for treatment benefit from other therapeutic approaches. Continuous deep sedation (CDS) or Continuous deep sedation until death (CDSUD) could be selected if suffering is intense and definitely refractory, the patient’s wish is explicit, death is anticipated within hours or a few days, or in the setting of an end-of-life catastrophic event such as massive haemorrhage or asphyxia (2).

2Assisted dying: We use this terminology, which refers in this article to physician assisted suicide and euthanasia without further differentiation.

3Definition of Existential Analysis: A phenomenological and person-oriented psychotherapy, with the aim of leading the person to (mentally and emotionally) free experiences, to facilitate authentic decisions and to bring about a truly responsible way of dealing with life and the world. Thus, Existential Analysis can be applied in cases of psychosocial, psychosomatic and psychological caused disorder in experience and behaviour (38).

References

- Shakespeare W. Hamlet-Speech: “To be, or not to be, that is the question” [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 31]. Available online: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56965/speech-to-be-or-not-to-be-that-is-the-question

- Cherny NI, Radbruch LBoard of the European Association for Palliative Care. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliat Med 2009;23:581-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klein C, Voss R, Ostgathe C, et al. Sedation in Palliative Care—a Clinically Oriented Overview of Guidelines and Treatment Recommendations. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2023;120:235-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Surges SM, Garralda E, Jaspers B, et al. Review of European Guidelines on Palliative Sedation: A Foundation for the Updating of the European Association for Palliative Care Framework. J Palliat Med 2022;25:1721-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schildmann E, Schildmann J. Palliative sedation therapy: a systematic literature review and critical appraisal of available guidance on indication and decision making. J Palliat Med 2014;17:601-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abarshi E, Rietjens J, Robijn L, et al. International variations in clinical practice guidelines for palliative sedation: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:223-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weixler D, Roider-Schur S, Likar R, et al. Leitlinie zur Palliativen Sedierungstherapie (Langversion): Ergebnisse eines Delphiprozesses der Österreichischen Palliativgesellschaft (OPG). Wien Med Wochenschr 2017;167:31-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Graeff A, Dean M. Palliative sedation therapy in the last weeks of life: a literature review and recommendations for standards. J Palliat Med 2007;10:67-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bozzaro C. Der Leidensbegriff im medizinischen Kontext: Ein Problemaufriss am Beispiel der tiefen palliativen Sedierung am Lebensende. Ethik Med 2015;27:93-106. [Crossref]

- Frankl VE. Ärztliche Seelsorge: Grundlagen der Logotherapie und Existenzanalyse: mit den zehn Thesen über die Person. 11., überarbeitete Auflage. Wien: Deuticke Verlag; 2005. 351 p.

- Kissane DW, Bobevski I, Appleton J, et al. Real World Experience of Change in Psycho-Existential Symptoms in Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2023;66:212-220.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson S, Kissane DW, Brooker J, et al. A systematic review of the demoralization syndrome in individuals with progressive disease and cancer: a decade of research. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:595-610. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gan LL, Gong S, Kissane DW. Mental state of demoralisation across diverse clinical settings: A systematic review, meta-analysis and proposal for its use as a ‘specifier’ in mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2022;56:1104-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gabl C. „Das Leiden muss ein Ende haben!” Existenzielles Leiden und der Wunsch nach einem raschen Tod – ein belastendes Spannungsfeld für Palliativpatienten, Angehörige und Betreuungspersonen. In: Feichtner A, Körtner U, Likar R, et al., editors. Assistierter Suizid [Internet]. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2022. p. 203-16.

- Kissane DW, Appleton J, Lennon J, et al. Psycho-Existential Symptom Assessment Scale (PeSAS) Screening in Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;64:429-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bozzaro C. Schmerz und Leiden als anthropologische Grundkonstanten und als normative Konzepte in der Medizin. In: Maio G, Bozzaro C, Eichinger T, editors. Leid und Schmerz: Konzeptionelle Annäherungen und medizinethische Implikationen. Originalausgabe. Freiburg; München: Verlag Karl Alber; 2015. p. 432.

- Rosa H. The uncontrollability of the world. 1st ed. Cambridge Medford (Md.): Polity press; 2020. 140 p.

- Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med 1982;306:639-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Goals of Medicine. Setting New Priorities. Hastings Cent Rep 1996;26:S1-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, et al. Palliative Care: The World Health Organization’s Global Perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:91-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Hooft S. Suffering and the goals of medicine. Med Health Care Philos 1998;1:125-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruce A, Boston P. Relieving existential suffering through palliative sedation: discussion of an uneasy practice. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:2732-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Streeck N. Death without distress? The taboo of suffering in palliative care. Med Health Care Philos 2020;23:343-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kissane DW. Demoralization: a life-preserving diagnosis to make for the severely medically ill. J Palliat Care 2014;30:255-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Svenaeus F. The phenomenology of suffering in medicine and bioethics. Theor Med Bioeth 2014;35:407-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boston P, Bruce A, Schreiber R. Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: an integrated literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:604-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grech A, Marks A. Existential Suffering Part 1: Definition and Diagnosis #319. J Palliat Med 2017;20:93-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LeMay K, Wilson KG. Treatment of existential distress in life threatening illness: a review of manualized interventions. Clin Psychol Rev 2008;28:472-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer T, Klimecki OM. Empathy and compassion. Curr Biol 2014;24:R875-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blondeau D, Roy L, Dumont S, et al. Physicians’ and Pharmacists’ Attitudes toward the use of Sedation at the End of Life: Influence of Prognosis and Type of Suffering. J Palliat Care 2005;21:238-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson S, Kissane DW, Brooker J, et al. A Review of the Construct of Demoralization: History, Definitions, and Future Directions for Palliative Care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2016;33:93-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson S, Kissane DW, Brooker J, et al. Refinement and revalidation of the demoralization scale: The DS-II-internal validity. Cancer 2016;122:2251-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM. Dying, dignity, and new horizons in palliative end-of-life care. CA Cancer J Clin 2006;56:84-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. BMJ 2007;335:184-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, et al. The patient dignity inventory: a novel way of measuring dignity-related distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;36:559-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:753-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Philipp R, Kalender A, Härter M, et al. Existential distress in patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: study protocol of a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e046351. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- What is Existential Analysis and Logotherapy? [Internet]. GLE International - Gesellschaft für Logotherapie und Existenzanalyse. [cited 2023 Oct 31]. Available online: https://www.existenzanalyse.org/en/introduction/

- Cornu P. Dictionnaire encyclopédique du bouddhisme. Nouv. édition augmentée. Paris: Seuil; 2006.

- Three types of suffering. In: Rigpa Shedra Wiki [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 31]. Available online: https://www.rigpawiki.org/index.php?title=Three_types_of_suffering

- Strang P, Strang S, Hultborn R, et al. Existential pain—an entity, a provocation, or a challenge? J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;27:241-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Längle A, Bürgi D, Köhlmeier M. Wenn das Leben pflügt: Krise und Leid als existentielle Herausforderung. Göttingen Bristol, CT, U.S.A: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; 2016. 121 p. (Edition Leidfaden).

- Frankl VE. Der Wille zum Sinn. 7., unveränderte Auflage. Bern: Hogrefe; 2016. 263 p. (Klassiker der Psychologie).

- Längle A. Existential Analysis – The search for an approval of life [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mai 31]. Available online: https://www.existenzanalyse.org/en/introduction/existential-analysis/

- Längle A. Die Grundmotivationen menschlicher Existenz als Wirkstruktur existenzanalytischer Psychotherapie. Fundam Psychiatr 2002;16:1-8.

- Längle A. Warum wir leiden: Verständnis, Umgang und Behandlung von Leiden aus existenzanalytischer Sicht. Existenzanalyse 2009;29:20-9.

- Frankl VE. Der leidende Mensch: anthropologische Grundlagen der Psychotherapie. 4., unveränderte Auflage. Bern: Hogrefe; 2018. 253 p. (Klassiker der Psychologie).

- Längle A. Sinnvoll leben: eine praktische Anleitung der Logotherapie. Neuausgabe, 3. Auflage. Bürgi D, editor. St. Pölten Salzburg Wien: Residenz Verlag; 2014. 134 p.

- Schnell T. Psychologie des Lebenssinns. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2016. 195 p.

- Breitbart W, Heller KS. Reframing Hope: Meaning-Centered Care for Patients Near the End of Life. J Palliat Med 2003;6:979-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2010;19:21-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kissane DW. The relief of existential suffering. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1501-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Winger JG, Adams RN, Mosher CE. Relations of meaning in life and sense of coherence to distress in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2016;25:2-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. 218 p. (A Joint publication in the Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series and the Jossey-Bass health series).

- Längle A. Hoffnung - Ausdruck der Liebe zum Leben. In: Müller M, Radbruch L, editors. Hoffnung - ein Drahtseilakt. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; 2017. p. 9-12. (Leidfaden).

- Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, et al. ‘Unbearable suffering’: a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients who request assistance in dying. J Med Ethics 2011;37:727-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Längle A. Existenzanalyse: existentielle Zugänge der Psychotherapie. Wien: Facultas; 2016. 240 p.

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA 2000;284:2907-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Depression, Hopelessness, and suicidal ideation in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics 1998;39:366-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM. Intensive Caring: Reminding Patients They Matter. J Clin Oncol 2023;41:2884-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1185-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ganzini L, Harvath TA, Jackson A, et al. Experiences of Oregon nurses and social workers with hospice patients who requested assistance with suicide. N Engl J Med 2002;347:582-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodin G, Zimmermann C, Rydall A, et al. The desire for hastened death in patients with metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:661-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balaguer A, Monforte-Royo C, Porta-Sales J, et al. An International Consensus Definition of the Wish to Hasten Death and Its Related Factors. PLoS One 2016;11:e0146184. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vehling S, Kissane DW, Lo C, et al. The association of demoralization with mental disorders and suicidal ideation in patients with cancer. Cancer 2017;123:3394-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson S, Kissane DW, Brooker J, et al. The Relationship Between Poor Quality of Life and Desire to Hasten Death: A Multiple Mediation Model Examining the Contributions of Depression, Demoralization, Loss of Control, and Low Self-worth. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:243-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hatano Y, Morita T, Mori M, et al. Complexity of desire for hastened death in terminally ill cancer patients: A cluster analysis. Palliat Support Care 2021;19:646-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maeda S, Morita T, Yokomichi N, et al. Continuous Deep Sedation for Psycho-Existential Suffering: A Multicenter Nationwide Study. J Palliat Med 2023;26:1501-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. 313 p.

- Cassell EJ, Rich BA. Intractable end-of-life suffering and the ethics of palliative sedation. Pain Med 2010;11:435-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hartogh GD. Sedation Until Death: Are the Requirements Laid Down in the Guidelines Too Restrictive? Kennedy Inst Ethics J 2016;26:369-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saunders CM. Watch with me: inspiration for a life in hospice care. Lancaster, UK: Observatory Publications; 2005.

- Rodin G, Lo C, Mikulincer M, et al. Pathways to distress: the multiple determinants of depression, hopelessness, and the desire for hastened death in metastatic cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:562-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Snaith RP. The concepts of mild depression. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:387-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clarke DM, Kissane DW. Demoralization: its phenomenology and importance. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2002;36:733-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kissane DW. Education and assessment of psycho-existential symptoms to prevent suicidality in cancer care. Psychooncology 2020;pon.5519. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:

10.1002/pon.5519 .10.1002/pon.5519 - Lichtenthal WG, Nilsson M, Zhang B, et al. Do rates of mental disorders and existential distress among advanced stage cancer patients increase as death approaches? Psychooncology 2009;18:50-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morita T. Palliative sedation to relieve psycho-existential suffering of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;28:445-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohnsorge K, Gudat H, Rehmann-Sutter C. Intentions in wishes to die: analysis and a typology – A report of 30 qualitative case studies of terminally ill cancer patients in palliative care. Psychooncology 2014;23:1021-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belar A, Martinez M, Centeno C, et al. Wish to die and hasten death in palliative care: a cross-sectional study factor analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021;bmjspcare-2021-003080.

- Wilson KG, Dalgleish TL, Chochinov HM, et al. Mental disorders and the desire for death in patients receiving palliative care for cancer. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:170-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Prat A, Balaguer A, Booth A, et al. Understanding patients’ experiences of the wish to hasten death: an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016659. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chávez C, Tomás-Sábado J, et al. What lies behind the wish to hasten death? A systematic review and meta-ethnography from the perspective of patients. PLoS One 2012;7:e37117. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lamm C, Decety J, Singer T. Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. Neuroimage 2011;54:2492-502. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer T, Lamm C. The social neuroscience of empathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009;1156:81-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Decety J, Jackson PL. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev 2004;3:71-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klimecki O, Ricard M, Singer T. Empathy versus Compassion - Lessons from 1st and 3rd Person Methods. In: Singer T, Bolz M, editors. Compassion: Bridging Practice in Science [Internet]. Munich: Max Planck Society; 2013. p. 272–87.

- Cherny NI, Ziff-Werman B, Kearney M. Burnout, compassion fatigue, and moral distress in palliative care. In: Cherny NI, Fallon MT, Kaasa S, et al., editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2021. p. 166-80.

- Morita T, Akechi T, Sugawara Y, et al. Practices and attitudes of Japanese oncologists and palliative care physicians concerning terminal sedation: a nationwide survey. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:758-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gray TF, Azizoddin DR, Nersesian PV. Loneliness among cancer caregivers: A narrative review. Palliat Support Care 2020;18:359-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Applebaum AJ, Farran CJ, Marziliano AM, et al. Preliminary study of themes of meaning and psychosocial service use among informal cancer caregivers. Palliat Support Care 2014;12:139-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology 2010;19:1013-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robijn L, Seymour J, Deliens L, et al. The involvement of cancer patients in the four stages of decision-making preceding continuous sedation until death: A qualitative study. Palliat Med 2018;32:1198-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, et al. Caregivers of advanced cancer patients: feelings of hopelessness and depression. Cancer Nurs 2007;30:412-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nielsen MK, Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, et al. Preloss grief in family caregivers during end-of-life cancer care: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Psychooncology 2017;26:2048-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Philipp R, Mehnert A, Müller V, et al. Perceived relatedness, death acceptance, and demoralization in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:2693-700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mosher CE, Jaynes HA, Hanna N, et al. Distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients: an examination of psychosocial and practical challenges. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:431-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gamondi C, Larkin P, Payne S. Core competencies in palliative care: an EAPC White Paper on palliative care education – part 2. Eur J Palliat Care 2013;20:140-5.

- Grech A, Marks A. Existential Suffering Part 2: Clinical Response and Management #320. J Palliat Med 2017;20:95-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, et al. Eliciting Personhood Within Clinical Practice: Effects on Patients, Families, and Health Care Providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:974-80.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Patient Dignity Question [Internet]. Dignity in care. [cited 2023 Oct 31]. Available online: https://www.dignityincare.ca/en/the-patient-dignity-question.html

- Hadler RA, Goldshore M, Rosa WE, et al. “What do I need to know about you?”: the Patient Dignity Question, age, and proximity to death among patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2022;30:5175-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hartogh GD. Suffering and dying well: on the proper aim of palliative care. Med Health Care Philos 2017;20:413-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jansen LA, Sulmasy DP. Proportionality, terminal suffering and the restorative goals of medicine. Theor Med Bioeth 2002;23:321-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Breitbart W. Spirituality and meaning in supportive care: spirituality- and meaning-centered group psychotherapy interventions in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:272-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy: an effective intervention for improving psychological well-being in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:749-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld B, Cham H, Pessin H, et al. Why is Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy (MCGP) effective? Enhanced sense of meaning as the mechanism of change for advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology 2018;27:654-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fegg M, Kudla D, Brandstätter M, et al. Individual meaning in life assessed with the Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation: toward a circumplex meaning model. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:91-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fegg MJ, Kramer M, L'hoste S, et al. The Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation (SMiLE): validation of a new instrument for meaning-in-life research. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:356-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nissim R, Freeman E, Lo C, et al. Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM): a qualitative study of a brief individual psychotherapy for individuals with advanced cancer. Palliat Med 2012;26:713-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sethi R, Rodin G, Hales S. Psychotherapeutic Approach for Advanced Illness: Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM) Therapy. Am J Psychother 2020;73:119-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seymour J, Rietjens J, Bruinsma S, et al. Using continuous sedation until death for cancer patients: A qualitative interview study of physicians’ and nurses’ practice in three European countries. Palliat Med 2015;29:48-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heijltjes MT, Morita T, Mori M, et al. Physicians’ Opinion and Practice With the Continuous Use of Sedatives in the Last Days of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;63:78-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schur S, Weixler D, Gabl C, et al. Sedation at the end of life - a nation-wide study in palliative care units in Austria. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beller EM, van Driel ML, McGregor L, et al. Palliative pharmacological sedation for terminally ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;1:CD010206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deschepper R, Laureys S, Hachimi-Idrissi S, et al. Palliative sedation: why we should be more concerned about the risks that patients experience an uncomfortable death. Pain 2013;154:1505-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanders RD, Tononi G, Laureys S, et al. Unresponsiveness ≠ unconsciousness. Anesthesiology 2012;116:946-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noreika V, Jylhänkangas L, Móró L, et al. Consciousness lost and found: subjective experiences in an unresponsive state. Brain Cogn 2011;77:327-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weixler D, Paulitsch K. Praxis der Sedierung. Wien: Facultas; 2003. 637 p. (Vademecum).

- Heijltjes MT, van Thiel GJMW, Rietjens JAC, et al. Changing Practices in the Use of Continuous Sedation at the End of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:828-846.e3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chambaere K, Vander Stichele R, Mortier F, et al. Recent trends in euthanasia and other end-of-life practices in Belgium. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1179-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bosshard G, Zellweger U, Bopp M, et al. Medical End-of-Life Practices in Switzerland: A Comparison of 2001 and 2013. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:555-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Heide A, van Delden JJM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. End-of-Life Decisions in the Netherlands over 25 Years. N Engl J Med 2017;377:492-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues P, Ostyn J, Mroz S, et al. Ethics of sedation for existential suffering: palliative medicine physician perceptions - qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2023;13:209-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. Eighth edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2019. 496 p.

- Rietjens JAC, Heijltjes MT, van Delden JJM, et al. The Rising Frequency of Continuous Deep Sedation in the Netherlands, a Repeated Cross-Sectional Survey in 2005, 2010, and 2015. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20:1367-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raus K, Sterckx S, Mortier F. Continuous deep sedation at the end of life and the ‘natural death’ hypothesis. Bioethics 2012;26:329-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hasselaar JG, Verhagen SC, Wolff AP, et al. Changed patterns in Dutch palliative sedation practices after the introduction of a national guideline. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:430-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seymour JE, Janssens R, Broeckaert B. Relieving suffering at the end of life: Practitioners’ perspectives on palliative sedation from three European countries. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:1679-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morita T, Rietjens JA, Imai K, et al. Authors’ Reply to Twycross. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:e15-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hutter N, Stößel U, Meffert C, et al. Was ist „gutes Sterben”? DMW - Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2015;140:1296-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hales S, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. The quality of dying and death. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:912-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patrick DL, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of dying and death. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:410-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krikorian A, Maldonado C, Pastrana T. Patient’s Perspectives on the Notion of a Good Death: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;59:152-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meier EA, Gallegos JV, Thomas LP, et al. Defining a Good Death (Successful Dying): Literature Review and a Call for Research and Public Dialogue. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;24:261-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lang A, Frankus E, Heimerl K. The perspective of professional caregivers working in generalist palliative care on ‘good dying’: An integrative review. Soc Sci Med 2022;293:114647. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maio G. Gutes Sterben erfordert mehr als die Respektierung der Autonomie. Dtsch Z Für Onkol 2011;43:129-31. [Crossref]

- Cottrell L, Duggleby W. The “good death”: An integrative literature review. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:686-712. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phillips WR, Uygur JM, Egnew TR. A Comprehensive Clinical Model of Suffering. J Am Board Fam Med 2023;36:344-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, McClement SE, Hack TF, et al. Health care provider communication: an empirical model of therapeutic effectiveness. Cancer 2013;119:1706-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AWMF. AWMF-Regelwerk Leitlinien: Von der Planung bis zur Publikation [Internet]. Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) e. V; [cited 2023 Oct 31]. Available online: https://www.awmf.org/regelwerk/

- Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:iii-iv, 1-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muller-Busch HC, Andres I, Jehser T. Sedation in palliative care - a critical analysis of 7 years experience. BMC Palliat Care 2003;2:2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schuman-Olivier Z, Brendel DH, Forstein M, et al. The use of palliative sedation for existential distress: a psychiatric perspective. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2008;16:339-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Lo B, Brock DW, et al. Last-resort options for palliative sedation. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:421-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cherny NI. ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life and the use of palliative sedation. Ann Oncol 2014;25:iii143-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Twycross R. Reflections on palliative sedation. Palliat Care 2019;12:1178224218823511. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Radbruch L, Payne SEAPC Board of Directors. White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 1. Eur J Palliat Care 2009;16:278-89.

- Schildmann EK, Bausewein C, Schildmann J. Palliative sedation: Improvement of guidelines necessary, but not sufficient. Palliat Med 2015;29:479-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues P, Crokaert J, Gastmans C. Palliative Sedation for Existential Suffering: A Systematic Review of Argument-Based Ethics Literature. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:1577-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Twycross R. Regarding Palliative Sedation. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:e13-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cherny NI, Portenoy RK. Sedation in the management of refractory symptoms: guidelines for evaluation and treatment. J Palliat Care 1994;10:31-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bozzaro C. Ärztlich assistierter Suizid: Kann „unerträgliches Leiden” ein Kriterium sein? DMW - Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2015;140:131-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Tol D, Rietjens J, van der Heide A. Judgment of unbearable suffering and willingness to grant a euthanasia request by Dutch general practitioners. Health Policy 2010;97:166-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bozzaro C, Schildmann J. “Suffering” in Palliative Sedation: Conceptual Analysis and Implications for Decision Making in Clinical Practice. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:288-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cherny NI. Commentary: sedation in response to refractory existential distress: walking the fine line. J Pain Symptom Manage 1998;16:404-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saunders C. The treatment of intractable pain in terminal cancer. Proc R Soc Med 1963;56:195-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alt-Epping B. Palliative sedation: controversial discussions and appropriate practice. Dtsch Ärztebl Int [Internet] 2022 May 27 [cited 2023 Oct 31]; Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0212

- Belar A, Arantzamendi M, Menten J, et al. The Decision-Making Process for Palliative Sedation for Patients with Advanced Cancer-Analysis from a Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:301. [Crossref] [PubMed]