Integrating palliative care in patients with advanced multiple sclerosis: a scoping review

Highlight box

Key findings

• The main objective of this research was to map and to update the integration of palliative care (PC) in patients with advanced multiple sclerosis (MS).

What is known and what is new?

• Studies merely note that patients with MS should have access to specialized PC when they reach the severe phase of the disease, being referenced as early as possible, as well as ensuring advanced care planning.

• PC in advance MS is financially efficient: home PC has also been reported to be financially advantageous.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Integration of specialized PC services in prolonged neurological conditions, and this should be a priority for the research and formulation of national and international policies.

• Special attention should be given to the need for training of health professionals.

• Reference criteria for the integration of MS patients in PC should be created.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) generally becomes more severe over time (1). However, there is no specific timeline that this condition follows. Each patient will have their own experience of the illness; some may never reach an advanced stage of the disease (1). However, if MS progresses to advanced stages, quality of life can be significantly affected by symptoms, requiring the support of third parties and specialized professionals as a whole (2).

Despite improvements in palliative care (PC), its access remains inconsistent, even in developed countries. Overall, only a small proportion (14%) of those who need PC receive this type of care (3). In contrast, with the trajectory of non-malignant diseases, MS often presents a long and uncertain evolution (4). While robust evidence supports treatment decisions in advanced MS, recent guidelines suggest incorporating a palliative approach as the disease progresses (5-7).

Even though patients with chronic non-oncologic diseases, including long-term neurological conditions, experience problems and challenges similar to patients with advanced cancer, they are less likely to receive PC (8). The long trajectory of MS and uncertain prognosis suggests the need for a PC model different from cancer (9).

Most studies on the effectiveness of PC in patients with MS have focused on the quality of life and symptoms burden (3). The main cost components in PC with more advanced diseases are production losses, hospitalizations, and informal care (9). Recent studies show that PC improves patient and family satisfaction. This care is also related to reducing hospital costs, mainly due to the shorter hospital stay, less use of intensive care units, and less use of emergency services (5-7).

An interaction between the specialties of neurology, physical medicine rehabilitation, and PC should be assumed, with a view to a comprehensive and effective patient management approach (5,10). There are barriers to PC in MS. MS has an unpredictable trajectory (1). It is difficult to frame MS as a disease needing PC by users and health professionals (4-7). There is also a deficit in healthcare structures for PC (4-7). A small percentage of users receive PCs when needed (3). Overall, there has been little education and training for neurologists in the PC area since the residency program. Some skills, particularly in communication, can be learned with appropriate training and experience (9).

The main objective of this research is to map and to update the integration of PC in patients with advanced MS. Specifically, to identify the practice and efficacy of PC in patients with advanced MS, recognize the appropriate moment during the disease for referral to PC, and understand the perception of advanced MS patients, their relatives, and health professionals, regarding PC. This research aims to update the knowledge about PC in patients with severe MS. It is intended to inform about new guidelines and justify the need for the creation of an integrated service of neuropalliative care, as well as of reference criteria for integration in these services. This scoping review was based on the principles recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute and the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist (11,12) (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-455/rc).

Methods

A scoping review was conducted by searching the following databases: Scopus, Medline (PubMed), ISI Web of Knowledge, and SAGE, published between January 2011 to December 2022. The keywords “multiple sclerosis” AND “palliative care” were used. In the Medline database, these terms were used as Mesh Terms.

It is a mixed method review, so it involves the combination of quantitative and qualitative studies for data synthesis and transformation (13). The typology of articles included was randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, controlled before and after studies, quantitative and qualitative, presenting as criteria for inclusion: target population consisting of adult patients (aged 18 years or older) diagnosed with MS; therapeutic intervention integration into PC programs; and outcome related to the cost-effectiveness of the same. Studies on the perspectives of patients, caregivers, and health professionals regarding integrating PC were included. No restrictions were applied regarding the subtype of MS, gender, ethnicity, frequency of use of health services, and language. Review articles, opinions and reflections, and books or book chapters were used as exclusion criteria. Articles that presented other neurological conditions or that included the validation of evaluation instruments were also excluded.

The selection of the studies resulted from research, which took place on December 2nd, 2022, at 6.03 p.m. Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). The selection of the articles was conducted independently by two researchers. First, the selection was based on the titles and abstracts, followed by the full text, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data from the included studies were extracted and stored through the Microsoft Excel program.

Data was extracted manually and independently analyzed by the two researchers, namely study quality, eligibility and data synthesis and analysis. Any differing opinions regarding articles’ relevance and results were solved by reaching a consensus among the authors. Data analysis focused on the unmet needs of patients with MS and on the evaluation of cost-effectiveness of PC interventions in MS.

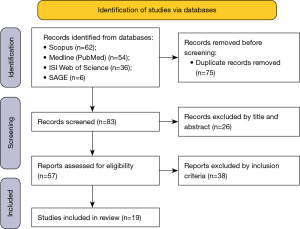

A total of 158 articles were identified in the databases. After the deletion of duplicate articles, 83 were analyzed based on the title and abstract, of which 26 articles were excluded. The remaining 57 full-text articles were analyzed, and 19 articles were included. A flow diagram following PRISMA guidelines was used to present the article selection process in Figure 1 (12).

Results

Of the 19 selected articles, the oldest is dated from 2011, and the most recent is from the year 2022. The largest number of publications occurred in 2014 (n=3; 15.8%), 2018 (n=3; 15.8%), and 2021 (n=3; 15.8%). Regarding its origin, the majority are from Germany (n=8; 42.1%).

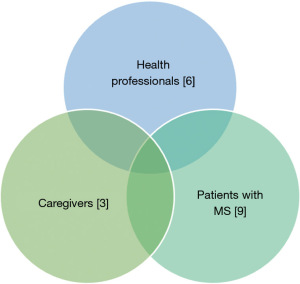

All the articles focused on PC, in various aspects, following the criteria previously established. The studies highlight the provision of PC relating to MS, with users (n=9; 47.4%), family members (n=3; 15.8%), and health professionals (n=6; 31.6%) as the main participants.

Given the systematization of the results, it was decided to present the data in two large groups. The first refers to the cost-effectiveness of PC intervention in users with MS (Table S1), including randomized prospective clinical trials—A (n=3; 15.8%) and retrospective studies—B (n=1; 5.3%) and studies related to the provision of this care through the telephone line—C (n=3; 15.8%). The table divides the studies into the country of origin, population, intervention performed, and results obtained through the PC intervention.

The second group points to the perception of the unmet needs of users with MS by users, caregivers, and health professionals (Table S2). Each study was analyzed for its origin, population, intervention performed, and results obtained through the PC intervention.

Understanding how the integration of PC is being carried out in these patients is fundamental to analyze new proposals for the provision of this type of care. However, it is crucial to understand the perspective of each of the actors involved in this process. Hence the need for clarification of the impact of these unmet needs on the provision of care.

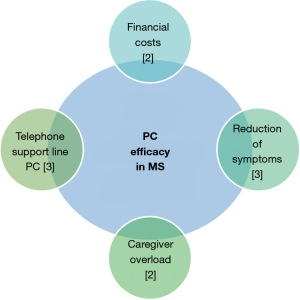

For a summarization of the essential elements of each study, an analysis of all the results was performed. Categories were then identified from the in-depth analysis of the articles, as they illustrated the factors that impact the effectiveness of care in users with MS (Figure 2). In addition, emerging categories were also grouped regarding unmet needs felt by users with MS, their caregivers and health professionals concerning the care provided (Figure 3).

Effectiveness of PC intervention in users with MS

Financial costs

Financial costs are a key parameter when assessing the effectiveness of a healthcare intervention. One of the retrospective studies included in this section (14) evaluated the time trends of PC in patients hospitalized from 2005 to 2014 in the United States of America (USA). They found that national trends in the use of PC increased 120-fold and that the proportion of PC intervention in in-hospital death gradually increased by 7.7% in 2005 and 58.8% in 2014. Hospital PC scans were associated with increased hospital stay and death but reduced hospital expenses (14).

Concerning the cost-effectiveness of this type of intervention, a study compared a palliative home approach and usual care. The authors report that the home PC presented lower costs than the conventional PC provided by the National Health Service (15).

Symptoms reduction

Reduction of symptomatology is a central aim of PC, and when treating severe MS. In these patients, the symptoms presented in advanced stages of the disease are like those presented throughout the disease, but with greater severity and leading to functional disability (16). Thus, the main symptoms presented in users diagnosed with MS, in an advanced stage, such as pain, nausea, vomiting, oral cavity problems, and sleep disorders, improve in patients undergoing PC intervention compared to conventional intervention (16). From the data found, it is verified that this improvement is maintained 12 weeks after the suspension of the intervention but not at 24 weeks (9). Higginson et al. also observed that early referral to the intervention of PC in MS has no significant evidence, compared to the later reference, regarding the reduction of symptomatology (9).

Caregiver overload

PC intervention represented a statistically significant effect in reducing caregiver burden (9). It is also notable that early referral to PC in this pathology plays a central role in reducing caregiver burden (9). Comparing the place of care with the presence of caregiver burden, Solari et al. (16), found there was no effect of home-based palliative approach (HPA) on the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) score, or interaction between intervention and center.

Telephone helpline

The German MS society reports that conventional health services for users diagnosed with advanced MS are insufficient to meet all patients’ needs. To put users with advanced MS in contact with the PC, a helpline was created that allows consultation/counseling from the domicile (17). A pilot study was developed allowing the access to PC through a direct national telephone line (17). Subsequently, this study was implemented by Strupp et al. in 2017 (18) and reevaluated in 2020 (19). The consultations included information on PC and hospice care (28.8%), access to PC and hospice care (by previous refusal 5.4%), general care of MS (36.1%), adequacy of housing (9.0%), and emotional support in crises (4.5%). In the evaluation carried out in 2020, there were 303 telephone calls, and PC or hospice care was indicated in 27.7% of these.

Perception of unmet needs

The unmet needs felt during the provision of PC in MS are widely addressed in the literature; to systematize the results, the different perspectives felt by the various stakeholders will be discussed below.

Health professionals

Regarding the perception of health professionals, it will be important to highlight that the perspectives of different professional groups (doctors, nurses, social workers, among others) were included, as well as the perspective of different specializations in the medical area (20).

Difficulty in framing PC in MS

Unanimity in the view of the medical group about the provision of PC in patients with MS is not verified. Neurologists associate PC at the end of life and are resistant to understanding the need for PC in this pathology (7). In the Golla et al. (21) study, most physicians felt that they had already offered their patients sufficient PC support, with no place for specialized care. These previous statements do not fit the view of PC physicians, who consider that they should be provided to users with severe degenerative pathology and should be performed in a specialized context (7). Turning their eyes to other groups of health professionals, nurses and social workers consider PC as an opportunity for patients with advanced MS (21).

Leclerc-Loiselle and Legault (22) report that health professionals generally feel that a PC approach for people living with advanced MS is mandatory; however, the main impediment to this provision of care is that health professionals do not feel comfortable systematically integrating them into their care delivery.

Lack of resources/structure of PC

Physicians in the PC understand that this type of care is essential for users with advanced MS, understanding that they are not exclusive to end-of-life care (7). These present as one of the main barriers to the lack of resources and how this care is being provided (7).

When studying nurses and social workers, it was found that they recognized the main difficulty of the deficits in existing healthcare structures (21).

Biopsychosocial-spiritual needs

In one of the studies included, a comparison was made between the unmet needs felt about PC by nurses and patients (2). The unmet needs were evaluated in the physical, social, spiritual, psychological, and financial dimensions. The study results showed that nurses provided a higher score regarding the physical dimension, followed by the social, spiritual, and psychological dimensions; the lowest score belonged to the financial dimension. It is important to highlight that the score returned to each of the dimensions by nurses was lower than the users’ evaluation (2).

Golla et al. (23) analyzed the unmet needs from the perspective of health professionals. The main categories identified were ‘support to family/friends’, ‘health services’, ‘managing daily life’, and ‘maintaining biographical continuity’. The main categories identified were ‘support to family/friends’, ‘health services’, ‘managing daily life’, and ‘maintaining biographical continuity’. While physicians assessed the most dissatisfied needs in the ‘health services’ category, nurses and social workers focused on unmet needs in the categories ‘support from family/friends’ and ‘maintaining biographical continuity’.

Concerning advance care planning (ACP), health professionals have difficulty initiating this conversation and choosing the ideal time to start this process. The unpredictable character of the disease hinders this management. However, health professionals understand, value, and have the skills and confidence to effectively engage in ACP-related conversations and processes. ACP should be seen as a ‘process over time’, not a ‘one-time’ event; revisiting/repeating conversations where necessary as MS progresses (24,25).

Patients with MS

Difficulty in framing PC in MS

Cheong et al. (7) report that users associate PC with end-of-life and struggle to understand the need for PC in this pathology.

Lack of resources/structure of PC

Bužgová et al. (3) evaluated two groups: the intervention group was offered a consultation with specific expertise of the multidisciplinary PC team and referral to the different team members as needed, and the control group was provided standard care through a regular check-up in the neurological center (once every 3 months). The intervention group showed greater satisfaction in all areas analyzed (relationship with the physician, disease management and decision/communication) and the functional status of the user. Users enrolling patients with more severe MS disease indicate that in the conventional care provided, the numbers of neurology consultations, home visits, and emotional support from the nursing team are insufficient (24).

Biopsychosocial-spiritual needs

Galushko et al. (26) point out the needs not met by users in the main categories of ‘support for family and friends’, ‘health services’, ‘manage daily life’, and ‘maintain biographical continuity’. Patients expressed the desire for greater family support and the need to be seen as distinct individuals. They find a substantial deficit in the doctor-patient relationship and the coordination of services.

For ACP, participants’ narratives focused on difficulties in planning for an uncertain future, perceived obstacles to engaging in ACP (that included uncertainty concerning MS disease progression), previous negative experiences of ACP discussions, and prioritizing symptom management over future planning (24).

Only Noormohammadi et al. (27) specifically aimed to clarify the spiritual dimension of patients with MS needing PC, and other two had a brief reference to this dimension in the studies by Bužgová et al. (3) and Dadsetan et al. (2). Holistic care requires an overview of human nature consisting of several aspects: physical, mental, social, and spiritual, and thus, the neglect of any dimension can create difficulties in achieving the established health objectives. During the interviews conducted with the users included in the study, for the explanation of the concept of spiritual care, the concepts of restoration of the identical essence and its nature, self-knowledge of the patient, the disease as a factor of proximity to God, were important, giving meaning to life and disease as a facilitator for the game of self-purification. According to the results of this research, caring for patients with MS requires dedication and attention to spiritual needs. Health planners should pay attention to this care and develop strategies to design spiritual interventions (27).

Caregivers

Lack of resources/structure of PC

Borreani et al. (6) added that the unmet needs felt by caregivers transcended medical issues and embraced organizational and psychosocial issues and health policies.

Biopsychosocial-spiritual needs

The main unmet needs were classified into the following categories: ‘relationship with the doctor’, ‘individual support of the health system’, ‘relationship with the individual severely affected by advanced MS’, ‘end-of-life issues’, and ‘self-care’ and ‘greater awareness of MS’. Users and their caregivers share these needs. The authors add that caregivers refer to their recipients’ unmet needs and not exactly their own (28).

Discussion

This review aimed to identify and understand the integration of PC in patients with advanced MS. Generally, the international literature points to some barriers and difficulties in implementing PC. In this study, we try to direct attention to MS, namely, to identify the practice and efficacy of this type of specialized care, as well as the appropriate phase for referral to PC, during the course of the disease. It is intended to inform about new guidelines and justify the need for the creation of an integrated service of neuropalliative care, as well as of reference criteria for integration in these services.

There is a consensus that the treatment of MS patients should be complex and include specialized PC services (7,29,30). Neuropalliative care should be the basis for providing care to patients with advanced MS in the advanced stage of the disease (7,30). In fact, when an increase in disability occurs, the clinical picture becomes more complicated, with various symptoms, such as fatigue, physical dysfunctions (e.g., problems of spasticity, swallowing or speech), intense pain, psychological/social distress, and cognitive impairment (31). However, all these disabling symptoms can occur at any stage of the clinical course (31). Quality of life can be defined as the individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of culture and value systems in which they are part of their objectives, expectations, standards, and concerns. Several aspects are defined, including systems associated with disease and treatment, physical function, psychological and social aspects, and those associated with family or work and economic factors (32). Quality of life is thus related to the individual’s ability to enjoy the activities of a normal life. Currently, one of the main objectives of health care is to improve the quality of life-related to health, in addition to the intended biological effects of cure, improvement or palliation of the disease and seeks to empower the individual for the management of his disease (33). The disease affects not only the patient but also his caregivers, family members, and any others who maintain effective close relationships with the former (34). In these circumstances, it is legitimate to question the welfare of those involved in this process, well-being, and resources that are often put to the test on this route. Caring for a palliative patient at home constitutes a challenge for the family/primary caregiver. Family support is a central concept in PC. The family/main caregiver hopes to find adequate answers to their needs to ensure their family member’s health and social care with the highest quality and dignity and may be subject to care overload (35). According to the current investigation, specialized PC services for patients with MS can positively affect symptoms and quality of life and may also reduce the burden on family members (7,10). It is important to highlight that users and caregivers who received specialized PC could discuss and manage the most severe symptoms and emotional problems more efficiently, as well as the possibilities of support services (3).

In this review, regarding the quality of life, contrary to what was stated by the international literature, there was no stated improvement with the implementation of PC in advanced MS; it should be noted that only a single study included a debate on this component (16). This information contradicts the overall essence of PC, based on the improvement of the symptomatology of the user and having as the core of their competencies the improvement of quality of life (36). Analyzing the perspective of the caregiver, it is verified that in all the studies included in this perspective, there was a positive effect in reducing the burden of caregivers (37). The early referral to the PC team also positively affected the caregiver’s burden (9).

An important recommendation was related to the ideal time for referring these patients to PC. It is recognized that this should occur as early as possible and before the terminal phase of the disease is reached (3). It is observed that this type of intervention presents a positive outcome regarding improving symptomatology (9). However, based on the results of the studies included in this review, we cannot conclude that an early referral will positively affect the reduction of symptom burden (9). Despite this, other literature suggests that professionals should discuss PC with their patients as soon as possible and establish, together with them, a plan for the approach, ensuring their autonomy (38). To help resolve this issue, it would be important to create referencing criteria. Identifying “signposts” of when to integrate PC into the treatment course of MS remains challenging, mainly because of patient symptomatic complexity and heterogeneity, yet there are already strong indications showing that PC can be a valuable complementary asset for this patient group (39). However, the Higginson et al. (9) study reveals that when one of the five symptoms are present: pain, nausea, vomiting, mouth problems and sleeping, users benefit from inclusion in PC. These symptoms can be seen as “flags” for when to integrate PC into routine MS management (39). An inadequate understanding of PC and the techniques for managing death and dying contributes to the early rationing of end-of-life care (28). Improvements in training and education should aim to address this inadequate knowledge.

The provision of PC has been shown to improve the quality of care and patient and family satisfaction and reduce costs (35). In the context of advanced MS, economic efficiency is further observed through decreased healthcare costs, shorter hospital stays, and increased deaths outside of healthcare facilities (3). This study confirms the financial benefits of home-based PC (15).

Regarding the most appropriate place for this care delivery, it is assumed that most patients with advanced-stage MS should remain at home, under the care of their caregivers (14,15). Hospice care is often recommended for patients with advanced MS. However, the organization of PC services varies widely among countries and health systems (40). To bridge this gap, patients in home care should receive treatment from a qualified interdisciplinary team, with regular home visits as needed (41). If difficult symptoms arise or hospital-level procedures are required, patients should have immediate access to a PC team. If hospitalization is necessary, patients should be admitted to a hospital department with the care of a PC service, neurology, or internal medicine (41).

With regard to the integration in PC, a German investigation on home PC with direct telephone hotline support found telephone interventions are helpful (18). When telephone interventions are included, patients are consulted relatively more frequently about their typical palliative symptoms, such as pain or psychosocial problems. Several studies have examined the unmet needs of MS patients. These studies indicate various needs related to medical help, assistance with daily living activities, psychosocial help, and other factors, such as rehabilitation and non-professional care (21,23,26,28). In addition to the physical burden, psychosocial circumstances, social isolation, and changes in the state of independence, relationships, and social functions also affect MS patients (38).

By knowing the unmet needs, it will be possible for us to design a more adequate model to overcome the flaws in the current model, whether these are in terms of resources and structures of the health care provided, the most suitable place to provide care, planning early care, symptom management, education and expertise of health professionals and caregivers, and emotional support (10). It is thought that if unmet needs are met, there will probably be a reduction in cost and improvement in effectiveness, given that a decrease in access to non-specialized care such as emergency services and hospitalizations will be predictable (9). One of the objectives of this review was to describe the perceptions of patients with advanced MS, their families, and health professionals regarding PC. These views are distinct, comparing the different prisms evaluated. Health professionals tend to score unmet needs at a lower level compared to patients themselves (7). Patients and neurologists share the idea that PC is intended for end-of-life care and struggle to understand the need for its integration into this pathology (7). On the other hand, palliative physicians cite the lack of resources as the main barrier to its implementation (7). In addition to these difficulties, many physicians feel that they already provide the necessary PC to their users; others do not feel comfortable integrating them systematically, and finally, the lack of specialized training in this intervention area is unanimous (2). These statements may be accounted for by the lack of knowledge about these themes (32). In addition to not understanding the benefits of this care, health professionals have difficulties in facing the inherent emotional aspects. Indeed, there is consensus on the lack of training for teams dealing with PC in MS (33,42,43).

Users have pointed out the unmet needs in the main categories of support (6,19,23). And caregivers tend to refer to the unmet needs of their recipients rather than their own (28). In the studies included in this review, caregivers’ unmet needs are omitted; most of the studies ignore the caregivers, and if they are included, this is in conjunction with the perspectives of users and not as a separate group (9). PC services could be better understood and improved if users and caregivers were evaluated separately (9).

ACP is a continuous, dynamic process of reflection and dialogue between an individual, those close to them, and their healthcare professionals concerning the individual’s preferences and values concerning future treatment and care, including end-of-life care (44). Koffman et al. (24) reported that health professionals have difficulty initiating conversations about ACP with MS patients and choosing the ideal time to start this process. Participants’ narratives focused on difficulties in planning an uncertain future, perceived obstacles to engaging in ACP (that included uncertainty concerning MS disease progression), previous negative experiences of ACP discussions, and prioritizing symptom management over future planning. Communication skills training and education/mentoring should be provided to health professionals working with MS users. And efforts should be made to understand structural and country-specific legal constraints related to ACP embed approaches and to evaluate the effectiveness of ACP for people with MS and their families, including quality improvement. ACP should be seen as a ‘process over time’, not a ‘one-time’ event; revisiting/repeating conversations where necessary as MS progresses (24).

Bužgová et al. (3) conducted a study to explore the potential of a PC intervention provided by a multidisciplinary team. They found that offering consultations tailored to the patient’s needs, with the option for family members to join, was of great benefit to both the patient and the caregiver. This suggests that people with advanced MS should receive specialized PC and that a unified European model should be developed. To ensure the effectiveness of such a model, training of health professionals should be guaranteed, both in basic and specialized courses (31).

This study has some limitations. The results presented are taken from a limited investigation body, sometimes with methodologies that present a reduced sample. It is important to note that studies reporting the intervention of PC in MS are reduced and present different approaches (home, hospital, among others). Overall, the body of available literature omits many aspects of health care without rehabilitation investigations and continuing care experiences. Cultural homogeneity also presents itself as a limitation of this review. Therefore, to achieve or maintain proportionate healthcare experiences, it is necessary to use high-quality qualitative research to gain a deeper understanding of the full healthcare experience for people with MS.

Conclusions

The main objective of this research was to map and understand the integration of PC in patients with advanced MS. Specifically, we have identified the practice and efficacy of PC in patients with advanced MS. PC in advance MS is financially efficient: reducing health care costs, shortening the duration of hospitalization, and increasing the number of deaths outside health facilities (3). Home PC has also been reported to be financially advantageous (14,15).

Regarding the ideal time for referring these users to PC, it was impossible to define a specific moment. The patients with MS should have access to specialized PC when they reach the severe phase of the disease, being referenced as early as possible (17). One of the appropriate options is providing a multidisciplinary team to provide targeted consultations based on the needs of patients (31). Personalized support, particularly in communication/decision-making, should be provided to older patients and patients with worse prognoses (31).

From the point of view of patients with advanced MS health professionals, all patients with MS have PC needs in the physical, social, spiritual, psychological, and economic dimensions, and patients should be able to access PC appropriate to their individual needs (26,28). It should have been considered that these issues have important implications for the future planning and provision of PC services (29).

Future research needs to identify the most appropriate way to improve the implementation of PC in advanced MS and other prolonged neurological conditions. The creation of benchmarks is crucial. The governing entities should address the integration of specialized PC services in prolonged neurological conditions, and this should be a priority for the research and formulation of national and international policies. Special attention should be given to the need for training of health professionals involved in the follow-up of this pathology.

Acknowledgments

This article is the product of a master’s thesis developed within the Master in Palliative Care at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Porto, Portugal. The dissertation can be found in the university repository.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-455/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-455/prf

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-455/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Hauser SL, Oksenberg JR. The neurobiology of multiple sclerosis: genes, inflammation, and neurodegeneration. Neuron 2006;52:61-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dadsetan F, Shahrbabaki PM, Mirzai M, et al. Palliative care needs of patients with multiple sclerosis in southeast Iran. BMC Palliat Care 2021;20:169. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bužgová R, Kozáková R, Bar M. Satisfaction of Patients With Severe Multiple Sclerosis and Their Family Members With Palliative Care: Interventional Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021;38:1348-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hubbard G, McLachlan K, Forbat L, et al. Recognition by family members that relatives with neurodegenerative disease are likely to die within a year: a meta-ethnography. Palliat Med 2012;26:108-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Methley AM, Chew-Graham C, Campbell S, et al. Experiences of UK health-care services for people with Multiple Sclerosis: a systematic narrative review. Health Expect 2015;18:1844-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borreani C, Bianchi E, Pietrolongo E, et al. Unmet needs of people with severe multiple sclerosis and their carers: qualitative findings for a home-based intervention. PLoS One 2014;9:e109679. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheong WL, Mohan D, Warren N, et al. Accessing palliative care for multiple sclerosis: A qualitative study of a neglected neurological disease. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019;35:86-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao W, Wilson R, Hepgul N, et al. Effect of Short-term Integrated Palliative Care on Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Patients Severely Affected With Long-term Neurological Conditions: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2015061. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Costantini M, Silber E, et al. Evaluation of a new model of short-term palliative care for people severely affected with multiple sclerosis: a andomized fast-track trial to test timing of referral and how long the effect is maintained. Postgrad Med J 2011;87:769-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solari A, Giordano A, Sastre-Garriga J, et al. EAN Guideline on Palliative Care of People with Severe, Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. J Palliat Med 2020;23:1426-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters M, Godfrey CM, Khall H, et al. 2017 Guidance for the Conduct of JBI Scoping Reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z. editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372: [PubMed]

- Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, et al. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synth 2020;18:2108-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee YJ, Yoo JW, Hua L, et al. Ten-year trends of palliative care utilization associated with multiple sclerosis patients in the United States from 2005 to 2014. J Clin Neurosci 2018;58:13-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosato R, Pagano E, Giordano A, et al. Living with severe multiple sclerosis: Cost-effectiveness of a palliative care intervention and cost of illness study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021;49:102756. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solari A, Giordano A, Patti F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a home-based palliative approach for people with severe multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2018;24:663-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knies AK, Golla H, Strupp J, et al. A palliative care hotline for multiple sclerosis: A pilot feasibility study. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1071-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strupp J, Groebe B, Knies A, et al. Evaluation of a palliative and hospice care telephone hotline for patients severely affected by multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Eur J Neurol 2017;24:1518-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strupp J, Groebe B, Voltz R, et al. Follow-Ups with callers of a palliative and hospice care hotline for severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: Evaluation of its impact. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020;42:102079. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Afonso Henriques AD. Direção Geral da Saúde Organização de Cuidados na Esclerose Múltipla, EDSS. 2012. Available online: https://www.dgs.pt/

- Golla H, Galushko M, Pfaff H, et al. Multiple sclerosis and palliative care – perceptions of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients and their health professionals: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leclerc-Loiselle J, Legault A. Introduction of a palliative approach in the care trajectory among people living with advanced MS: perceptions of home-based health professionals. Int J Palliat Nurs 2018;24:264-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golla H, Galushko M, Pfaff H, et al. Unmet needs of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: the health professionals’ view. Palliat Med 2012;26:139-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koffman J, Penfold C, Cottrell L, et al. “I wanna live and not think about the future” what place for advance care planning for people living with severe multiple sclerosis and their families? A qualitative study. PLoS One 2022;17:e0265861. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strupp J, Romotzky V, Galushko M, et al. Palliative care for severely affected patients with multiple sclerosis: when and why? Results of a Delphi survey of health care professionals. J Palliat Med 2014;17:1128-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galushko M, Golla H, Strupp J, et al. Unmet needs of patients feeling severely affected by multiple sclerosis in Germany: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med 2014;17:274-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noormohammadi MR, Etemadifar S, Rabiei L, et al. Identification of Concepts of Spiritual Care in Iranian Peoples with Multiple Sclerosis: A Qualitative Study. J Relig Health 2019;58:949-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golla H, Mammeas S, Galushko M, et al. Unmet needs of caregivers of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: A qualitative study. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1685-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cottrell L, Economos G, Evans C, et al. A realist review of advance care planning for people with multiple sclerosis and their families. PLoS One 2020;15:e0240815. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oliver DJ, Borasio GD, Caraceni A, et al. A consensus review on the development of palliative care for patients with chronic and progressive neurological disease. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:30-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D’Amico E, Zanghì A, Patti F, et al. Palliative care in progressive multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother 2017;17:123-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Programme on mental health: WHOQOL user manual, 2012 revision. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/77932/WHO_HIS_HSI_Rev.2012.03_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Vidal De Figueiredo CA, Almeida De Lima EL, Santos HC, et al. Cuidados Paliativos e Esclerose Múltipla: Barreiras e problemas enfrentados. 2021. Doi:

10.29327/icidsuim2021.380247 .10.29327/icidsuim2021.380247 - Reis-Pina P, Santos RG. Early Referral to Palliative Care: The Rationing of Timely Health Care for Cancer Patients. Acta Med Port 2019;32:475-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Latorraca CO, Martimbianco ALC, Pachito DV, et al. Palliative care interventions for people with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;10:CD012936. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- May P, Normand C, Cassel JB, et al. Economics of Palliative Care for Hospitalized Adults With Serious Illness: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:820-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solari A, Giordano A, Grasso MG, et al. Home-based palliative approach for people with severe multiple sclerosis and their carers: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:184. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kümpfel T, Hoffmann LA, Pöllmann W, et al. Palliative care in patients with severe multiple sclerosis: two case reports and a survey among German MS neurologists. Palliat Med 2007;21:109-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strupp J, Voltz R, Golla H. Opening locked doors: Integrating a palliative care approach into the management of patients with severe multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2016;22:13-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Comissão Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos. Plano Estratégico para o Desenvolvimento CP 2017-2018. 2016. Available online: https://www.sns.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Plano-Estrat%C3%A9gico-para-o-Desenvolvimento-CP-2017-2018-2.pdf

- Alves RF, Andrade SF, Melo MO, et al. Cuidados paliativos: desafios para cuidadores e profissionais de saúde. Fractal Revista de Psicologia 2015;27:165-76.

- Giovannetti AM, Pietrolongo E, Giordano A, et al. Individualized quality of life of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: practicability and value in comparison with standard inventories. Qual Life Res 2016;25:2755-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Costello J. Preserving the independence of people living with multiple sclerosis towards the end of life. Int J Palliat Nurs 2017;23:474-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piers R, Albers G, Gilissen J, et al. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:88. [Crossref] [PubMed]