Do advanced cancer patients and their caregivers agree on preferred place of patient’s death?—a prospective cohort study of patient-caregiver dyads

Highlight box

Key findings

• Patient-caregiver dyads concordance for preference for place of death (PoD) changes over time at end-of-life (EOL).

What is known and what is new?

• Previous studies investigating patient-caregiver dyads concordance in preference for PoD were cross-sectional and unable to elucidate the changes in concordance at EOL.

• This study adds a longitudinal perspective on how concordance in preference for PoD changes at EOL and is associated with patient and caregiver factors.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• At EOL, balancing patients’ autonomy of choice and caregivers’ wellbeing is challenging.

• More effort is needed to understand patients’ EOL needs at home and alleviate caregivers’ distress.

Introduction

Where would you prefer to die—at home, in a hospital, in a hospice or elsewhere? It is an important preference that may be disregarded and unaddressed in the face of impending death. Globally, home death is preferred by many terminally ill cancer patients, motivated by presence of family and loved ones, and also a sense of normalcy (1-4). As a result, home deaths are regarded as a “gold standard” and a quality marker for end-of-life (EOL) care in many countries (5,6). However, a home death can be difficult to achieve, especially for patients who lack specialized home care and equipment (4,7). Uncertainties at EOL can also impose additional burden for family caregivers who enter their caregiving role underprepared for the challenges they may encounter (4,8,9). Even though caregiving for loved ones evokes values of filial piety, especially in many Asian cultures, it can inflict physical, financial and psychological burden on caregivers (8,10-12), and caregivers may prefer institutional death for patients to gain access to continuous professional help and symptomatic relief (13) even if their patient prefers to be at home.

Achieving patient-caregiver concordance can reduce distressing family conflicts and increase the likelihood of patients dying at their preferred place (14,15). Yet, few studies have investigated patient-caregiver concordance regarding preferred place of death (PPoD) (4,5,16-20). Patient characteristics, illness severity, effect of caregiving on family caregiver’s life and perception of caregiving burden have been reported to influence patient-caregiver concordance on PPoD (17,19,21-23). However, previous studies show that patients’ and caregivers’ preferences for EOL care change over time (21,23-25), as their illness progresses and caregiver burden evolves. Most studies assessing patient-caregiver concordance in preferences have, however, been cross-sectional (4,5,16-20,22,26,27); thus, it remains unclear on how changes in patients’ and caregivers’ preferences influence the concordance on their PPoD and if dyad concordance in PPoD could predict the actual place of death (PoD) (28-30).

Using data from a prospective cohort study, we first aimed to examine changes in patients’ and caregivers’ preference for home death and concordance in their preference for home death over the last 3 years of patients’ life. We hypothesized that majority of patient-caregiver dyads will be concordant in their preference for home death and this proportion will increase closer to patients’ death. Based on prior literature (17-19,21-23), we hypothesized that patient-caregiver concordance in preference for home death will be associated with patients’ symptom burden, history of hospitalization, financial difficulty; and caregivers’ competency, family support, psychological distress and spiritual wellbeing. Secondly, we aimed to examine whether concordance in preference for home death among patient-caregiver dyads was associated with their actual PoD. We hypothesized that patients will be more likely to die at home if the dyads are concordant in their preference for a home death. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-496/rc).

Methods

Design

We used data from Cost of Medical Care of Patients with Advanced Serious Illness in Singapore (COMPASS), a prospective cohort study of 600 patients with stage IV solid cancer (trial registration: NCT02850640) (31).

Sample and setting

Between July 2016 and March 2018, participants were recruited from outpatient medical oncology at two major public hospitals in Singapore. Eligible patients were aged ≥21 years, Singapore citizens or permanent residents, and cognitively able to consent, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status ≤2. Eligible caregivers were ≥21 years, providing or ensuring care, and legally acceptable representative of the patient (e.g., spouse/adult child). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (2015/2781) and informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Study variables

Patients and caregiver participants were administered a follow-up survey questionnaire every 3 months. The survey was administered either face-to-face or via telephone or via web survey link shared with the participants based on their individual preference. The survey questionnaire assessed a wide range of topics in their preferred language (English/Mandarin/Malay). The following measures were assessed:

Outcome

PoD

Patients’ preferences were assessed by asking “If you had a choice, where would you like to be during the last days of your life?” Similarly, caregivers’ preferences were assessed by asking “Where would you like (patient) to be during the last days of his/her life?” Responses were categorized as home and non-home death (institution (includes hospital, hospice, or nursing home) and unsure/others). We categorized hospital, hospice, and nursing homes together under institution because the proportion of participants preferring hospice and nursing homes was quite low to create a separate category. Concordance in patient-caregiver preference for home death was categorized as both patient and caregiver preferred a home death, neither preferred a home death, and only one of them preferred a home death. Actual PoD [home, or institution (hospital, hospice, nursing home, others)] was determined from medical records and caregivers’ reports.

Independent variables

Patients and caregiver characteristics

At baseline, patients and caregivers self-reported their sociodemographic (age, gender, relationship to patient/caregiver).

Financial difficulty

Financial difficulty was assessed by asking patients how well the amount of money they had enabled them to cover the cost of treatment, take care of their daily needs, and buy those little “extras” (32). A higher total score (range, 3–9) reflected higher financial difficulty.

Symptom burden

Patients reported severity of commonly reported symptoms (pain, shortness of breath, constipation, loss of weight, nausea, swelling, dryness of mouth and throat, fatigue, any other) on a Likert scale from 0 to 4 (not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much). The list of symptoms was adapted from the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Palliative Care (FACIT-Pal) and the total score from all items (range, 0–40) reflected the total symptom burden score (31,33).

Healthcare utilization

Patients’ number of inpatient admissions and length of hospital stay in the last 6 months of life were assessed using medical billing records.

Caregiver competency

Using the 4-item Caregiver Competence Scale validated for use among caregivers of palliative patients (34), caregivers’ rated each item on a Likert scale from 0 to 4 (not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much). A higher total score (range, 0–12) indicated greater competence.

Psychological distress

Caregivers psychological suffering was assessed using the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale validated for use in cancer patients in Singapore. A higher total score (range, 0–42) represented greater psychological distress (31,35).

Lack of family support

Caregivers’ family support was assessed using a subscale of the modified Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale (range, 1–5) validated for use in Singapore (31,36).

Spiritual outcomes

Caregivers’ spiritual wellbeing was assessed using a subscale of 12-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Spiritual (37)—meaning and faith. It was rated on a Likert scale from 0 to 4 (not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much). A higher total score (range, 0–42) represented better spiritual well-being.

Statistical analysis

We analysed data of patient-caregiver dyads who died between November 2016 and March 2022 and who had answered at least one survey during the last 3 years of (patients’) life. We described the baseline characteristics of patients and their caregivers and their PPoD (home and non-home death) was charted across time prior to death. This was repeated for patient-caregiver dyads who both preferred home death, did not prefer home death, and where either patient or caregiver preferred home death.

We conducted multivariable multinomial logistic regression models to assess association between preference for home death (both patient and caregiver preferred a home death, both did not prefer a home death, and either one of them preferred a home death) and the above listed independent variables. Mixed-effects regression models utilise all available data with repeated measurements overtime and uses maximum likelihood estimation to handle data missing at random (38). Lastly, we conducted a chi-square test to determine any association between actual PoD and PPoD assessed at the last survey closest to patient’s death.

Results

Out of the 1,042 eligible patients approached, 600 consented to records review and survey administration, and 311 had informal caregivers that consented to survey administration. Among the 311 patient-caregiver dyads, 82 patients were alive at the end of the study period and 2 patients did not answer the survey in the last 3 years of life, thus forming the analysis cohort of 227 dyads. Figure 1 illustrates the study recruitment process.

The average number of times [mean (standard deviation)] study participants responded to their PPoD in the last 3 years was 2 (0.8) (range, 1–4). The average time to death per patient was 11.8 (6.8) months (range, 0.2–35.4 months) for survey responses included in the analysis.

Table 1 describes patient and caregiver baseline characteristics at the beginning of last 3 years before patient’s death. Average age of patients was 62.6 years, 51.1% were male while 48.9% were female. Most of the patients died at an institution (64.8%) followed by home (32.6%). Average age of caregivers was 49.8 years and 63.0% were female. Nearly half of the caregivers (48.9%) were spouses of the patients.

Table 1

| Sample baseline characteristics | Patient, n (%) | Caregiver, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.6±10.3 | 49.8±14.7 |

| Female | 111 (48.9) | 143 (63.0) |

| Caregiver’s relationship with patient (patient is my…) | ||

| Spouse | – | 111 (48.9) |

| Parent | – | 85 (37.4) |

| Others | – | 31 (13.7) |

| Inpatient hospitalisation in the last 6 months, yes | 102 (44.9) | – |

| Actual place of death | ||

| Home | 74 (32.6) | – |

| Institutionala | 147 (64.8) | – |

| Unavailable information | 6 (2.6) | – |

| Symptom burden scoreb (range, 0–25) | 5.8±5.5 | – |

| Financial difficulties scorec (range, 3–9) | 6.0±1.6 | – |

| Caregiver competency scored (range, 2–12) | – | 8.8±2.0 |

| Psychological distresse (range, 0–35) | – | 10.3±7.5 |

| Lack of family support scoref (range, 1–5) | – | 2.3±0.6 |

| Spiritual well-being scoreg (range, 16–48) | – | 35.9±7.8 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). a, institutional death include hospital/hospice/care homes; b, symptoms from the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Palliative Care; c, amount of money to cover cost of treatment, take care of daily needs, and buy “extras”; d, measured using 4-item Caregiver Competence Scale; e, measured using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; f, measured using the modified Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale; g, measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Spiritual (meaning and faith).

Dyads’ preference for PoD in the last 3 years of patients’ life

Overall, in the last 3 years of life, 67% of the patients and 75% of the caregivers preferred a home death for patients. Proportion of caregivers who preferred home death decreased in the last year of patients’ life (77.5% to 62.9%) while preference for non-home death increased (22.5% to 37.1%) (Figure 2).

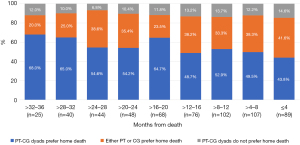

Concordance in dyads preference for home death in the last 3 years of patients’ life

Overall, more than half of the total observations from patient-caregiver dyads (54%) in the last 3 years of patient’s life were concordant in their preferences for home death. Twelve percent of the total observations were concordant in not preferring home death and 34% were discordant with either patient or caregiver preferring home death. Concordance in preference for home death decreased closer to death (68.0% to 43.8%). Conversely, discordance in preference for home death (either patient or caregiver preferred home death) increased as death approached (20.0% to 41.6%) (Figure 3).

Results from our multivariable logistic regression (Table 2) showed that dyads who preferred home death were less likely to involve older patients [relative risk ratio (RRR), 0.97; P=0.03]. Dyads who preferred a non-home death (hospital, hospice, nursing homes, unsure or others) were more likely to involve patients with greater symptom burden (RRR, 1.08; P=0.007) and spousal caregivers (RRR, 2.59; P=0.050) and less likely to involve caregivers with greater psychological distress (RRR, 0.90; P=0.003) and spiritual wellbeing (RRR, 0.92; P=0.007).

Table 2

| Predictor | Either patient or caregiver prefer home death (preference) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyads prefer home death | Dyads do not prefer home death | ||||||

| RRR | 95% CI | P value | RRR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Patient-related factors | |||||||

| Age, years | 0.97 | 0.95, 1.00 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.05 | 0.77 | |

| Financial difficulties | 1.01 | 0.87, 1.18 | 0.86 | 1.23 | 0.95, 1.59 | 0.11 | |

| Symptom burden | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.05 | 0.43 | 1.08 | 1.02, 1.15 | 0.007 | |

| Inpatient usage in the last 6 months, yes (vs. no) | 0.77 | 0.46, 1.31 | 0.33 | 1.16 | 0.48, 2.79 | 0.75 | |

| Caregiver-related factors | |||||||

| Spouse (vs. non-spouse) | 1.27 | 0.73, 2.23 | 0.40 | 2.59 | 1.00, 6.72 | 0.050 | |

| Caregiver competency | 1.11 | 0.98, 1.25 | 0.10 | 0.99 | 0.81, 1.20 | 0.90 | |

| Psychological distress | 0.96 | 0.93, 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.90 | 0.84, 0.96 | 0.003 | |

| Lack of family support | 1.21 | 0.82, 1.80 | 0.34 | 1.75 | 0.94, 3.23 | 0.08 | |

| Spiritual wellbeing | 1.00 | 0.97, 1.04 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.87, 0.98 | 0.007 | |

RRR, relative risk ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Contrary to hypothesis, we did not find any association between dyads’ concordance for a home death and patient’s financial difficulties, symptom burden, inpatient usage in the last 6 months of life and caregiver’s competency, psychosocial distress, perceived lack of family support and spiritual wellbeing (all P>0.05). Dyads’ concordance for a non-home death was not associated with patients’ age, financial difficulties, inpatient usage in the last 6 months of life; and caregiver self-perceived competency and lack of family support (all P>0.05).

Association between patient-caregiver dyads PPoD prior to death and patients’ actual PoD

Summary statistics (Table 3) showed that dyads who did not prefer a home death were the most likely group to have their preferences met (76.9%). Among dyads where both patients and caregivers preferred a home death at final survey assessment, 36.1% of patients died at home; where both patients and caregivers did not prefer a home death, 23.1% of patients died at home; where dyads were discordant in PPoD, 33.3% of patients died at home. Contrary to hypothesis, we did not find an association between actual PoD and patient-caregiver concordance in PPoD (P>0.05).

Table 3

| Dyads’ preference | Total, n (%) | Actual PoD (n=221)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home (n=74), n (%) | Institutionalb (n=147), n (%) | P value | ||

| PT-CG dyads prefer home death | 108 (48.9) | 39 (36.1) | 69 (63.9) | 0.45 |

| PT-CG dyads do not prefer home death | 26 (11.8) | 6 (23.1) | 20 (76.9) | |

| Either PT or CG prefer home death | 87 (39.4) | 29 (33.3) | 58 (66.7) | |

a, six PT-CG dyads were excluded from the analysis due to unavailable information about actual PoD; b, institutional death included hospital/hospice/nursing homes. PoD, place of death; PT, patient; CG, caregiver.

Discussion

This study used longitudinal data over last 3 years of patients’ life to assess changes in preference for home death among patients and caregivers, the extent of concordance between the dyads and investigated the patient and caregiver factors associated with dyad concordance over time. Lastly, we explored if concordance in dyads’ PPoD was associated with actual PoD.

We observed longitudinally that most patients and their caregivers preferred a home death, confirming previous cross-sectional studies (4,5,20,26,39). Dying at home is associated with physical and emotional comfort, and a safe place in contact with familiar people and environment (1-3). Cancer patients who die at home are also reported to have better quality of life at EOL than patients who die in hospitals (40).

We also showed that more than half of the total observations (54%) were concordant for home death. This is higher than Western literature where reportedly proportion of patients and caregivers preferring home death, ranges between 35% (21) and 32.6% (26). The differences may be attributed to the sociocultural context. In Asian societies under the influence of Confucian idea of filial piety, caregiving is seen as a repayment to parents or family members and caregivers may feel obliged to uphold the patients’ wishes (to die at home) (19,41). In Singapore, national healthcare policies are in place to encourage caring for family members in a home environment (30).

Our longitudinal analysis revealed and confirmed the dynamic nature of preferences for PoD (21,23-25). The proportion of caregivers who preferred a home death decreased as patients’ death approached, especially in the last year of life. This change may reflect the tumultuous challenges of the caregiving role. Despite emotional, physical and financial hardships, caregivers’ concerns for patients are likely to be more pragmatic, prioritizing quality of healthcare over their self-availability and ability to care for patients (8,42,43). In parallel, the extent of concordance for home death between patients and caregivers decreased as death approached, which is conflicting to the expectation that impending death fosters consensus (44).

What then influences patient-caregiver dyads’ concordance on preference for home death? We identified that dyads who preferred home death were less likely to involve older patients, consistent with previous studies (16,45). However, this is contrary to other Asian studies that suggest that death at home allows “fallen leaves to return to their roots” (18,41,46). The reasons for this contradiction require further exploration but it is possible that elderly patients may want to spare the family the burden of caring for them (22,47), or may feel relatively unsupported from the family, or there may have been a consensus decision that home cannot provide better care than institution.

On the other hand, dyads who did not prefer a home death were more likely to have patients with greater symptom burden. Severe symptoms may be difficult to control at home, requiring the need for more medical care (21) and thus discouraging dyads to be at home especially if they had already tried home care and suffered a negative experience (4,14).

Dyads who did not prefer home death were more likely to involve caregivers who were spouses. This was contrary to previous studies (16,19). Compared to non-spousal caregivers, spousal caregivers were more vulnerable to caregiving burden and depression as they need to simultaneously fulfil their supportive caregiving roles while facing ambiguity and potential loss of a partner (48-51).

However, concordant dyads who did not prefer home death (versus discordant dyads) involved caregivers with lower psychological distress and higher spiritual well-being. Association between caregiving and psychological distress has been widely established where caregivers caring for EOL patients are more likely to suffer from anxiety disorders and poorer mental health outcomes (48,52,53). Caregivers with lower distress may experience fewer conflicts with patients, better able to understand what patients prefer and thus have preferences concordant with those of their patients. On the other hand, higher spiritual well-being among caregivers can be a source of spiritual conflict with patients, which may negatively affect their relationship (51) and lead to discordance in preferences.

Does concordant dyads’ preference influence the actual PoD? Despite most of our dyads preferring a home death, we found that only 32.6% of patients ended up dying at home. We did not find any association between patient-caregiver concordance in PPoD and actual PoD. However, our results showed that among dyads that did not prefer to die at home, 77% of their patients actually died at an institution. This finding further emphasizes the need to identify factors that prevent the dyads who want a home death from achieving their desired PoD.

The main strength of the study is that findings are based on a prospective longitudinal design to capture the dynamic changes in PPoD in the setting of worsening illness and diminishing family resources as death approaches (4,5,16-20,22,26,27). However, there are few limitations, first, the associations observed could be biased by the self-reporting behaviours of patients and caregivers. Second, it is not possible to determine the causal inference due to non-experimental study-design. Third, PPoD for hospice and nursing homes could not be separated as their proportions were low in the dataset (for all available observations, patient’s preference for hospice—2.8% and nursing home—1.3% and caregiver’s preference for hospice—1.8% and nursing home—0.3%). Lastly, the findings are representative of the patients in specific geographic setting and may not be generalizable to all patients with advanced cancer. Future research should confirm the generalizability of our results in different clinical illnesses and cultural settings.

Despite these limitations, these results are informative. We longitudinally confirmed the discrepancy in PPoD between patients and their caregivers (18,20). While home death is regarded as a “gold standard” of EOL care, it is not possible for all deaths to be managed at home. It also reflects the challenges and practicality of balancing patients’ autonomy of choice and caregivers’ wellbeing. Our data suggest a greater need for effective interventions that not only revolve around understanding patients’ EOL needs and ensuring home-based symptom control but also a systematic approach to support caregivers and reduce their distress. Lastly, future research should seek to identify factors that prevent the dyads who want a home death from achieving their desired PoD.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study shows that dyads concordance for preference for home death decreases closer to death. Given the association between dyad concordance for preference for home death and patient age, symptom burden and caregivers’ distress, efforts need to be made to understanding the needs of older patients and optimizing home-based symptom control as well as provide resources to better support caregivers. Lastly, future research should identify factors that prevent the dyads who want a home death from achieving their desired PoD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the COMPASS study group for their contributions. The findings from this study have been previously presented in the MASCC/JASCC/ISOO Annual Meeting 2023, on 17 June 2023 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07933-x).

Funding: This work was supported by funding from

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-496/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-496/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-496/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-496/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (2015/2781) and the current study involves human subjects who provided their signed consent.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Lee EJ, Lee NR. Factors associated with place of death for terminal cancer patients who wished to die at home. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022;101:e30756. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nilsson J, Blomberg C, Holgersson G, et al. End-of-life care: Where do cancer patients want to die? A systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017;13:356-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valentino TCO, Paiva CE, de Oliveira MA, et al. Preference and actual place-of-death in advanced cancer: prospective longitudinal study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2023;spcare-2023-004299.

- Vidal M, Rodriguez-Nunez A, Hui D, et al. Place-of-death preferences among patients with cancer and family caregivers in inpatient and outpatient palliative care. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022;12:e501-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies A, Todd J, Bailey F, et al. Good concordance between patients and their non-professional carers about factors associated with a 'good death' and other important end-of-life decisions. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:340-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoare S, Antunes B, Kelly MP, et al. End-of-life care quality measures: beyond place of death. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Liu Z, Zheng R, et al. Exploring the needs and experiences of palliative home care from the perspectives of patients with advanced cancer in China: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 2021;29:4949-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chong E, Crowe L, Mentor K, et al. Systematic review of caregiver burden, unmet needs and quality-of-life among informal caregivers of patients with pancreatic cancer. Support Care Cancer 2022;31:74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerber K, Hayes B, Bryant C. 'It all depends!': A qualitative study of preferences for place of care and place of death in terminally ill patients and their family caregivers. Palliat Med 2019;33:802-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung H, Harding R, Guo P. Palliative Care in the Greater China Region: A Systematic Review of Needs, Models, and Outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021;61:585-612. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee HJ, Park SK. Factors Related to the Caregiving Burden on Families of Korean Patients With Lung Cancer. Clin Nurs Res 2022;31:1124-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Su J, Malhotra C. The cost of caring: How advanced cancer patients affect Caregiver's employment in Singapore. Psychooncology 2022;31:1152-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerlach C, Baus M, Gianicolo E, et al. What do bereaved relatives of cancer patients dying in hospital want to tell us? Analysis of free-text comments from the International Care of the Dying Evaluation (i-CODE) survey: a mixed methods approach. Support Care Cancer 2022;31:81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bannon F, Cairnduff V, Fitzpatrick D, et al. Insights into the factors associated with achieving the preference of home death in terminal cancer: A national population-based study. Palliat Support Care 2018;16:749-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- García-Sanjuán S, Fernández-Alcántara M, Clement-Carbonell V, et al. Levels and Determinants of Place-Of-Death Congruence in Palliative Patients: A Systematic Review. Front Psychol 2022;12:807869. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi KS, Chae YM, Lee CG, et al. Factors influencing preferences for place of terminal care and of death among cancer patients and their families in Korea. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:565-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gu X, Cheng W, Cheng M, et al. The preference of place of death and its predictors among terminally ill patients with cancer and their caregivers in China. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:835-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang ST, Liu TW, Lai MS, et al. Discrepancy in the preferences of place of death between terminally ill cancer patients and their primary family caregivers in Taiwan. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1560-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang ST, Chen CC, Tang WR, et al. Determinants of patient-family caregiver congruence on preferred place of death in taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:235-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valentino TCO, de Oliveira MA, Paiva CE, et al. Where do Brazilian cancer patients prefer to die? Agreement between patients and caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;64:186-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agar M, Currow DC, Shelby-James TM, et al. Preference for place of care and place of death in palliative care: are these different questions? Palliat Med 2008;22:787-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fukui S, Fujita J, Yoshiuchi K. Associations between Japanese people's concern about family caregiver burden and preference for end-of-life care location. J Palliat Care 2013;29:22-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malhotra C, Koh LE, Teo I, et al. A Prospective Cohort Study of Stability in Preferred Place of Death Among Patients With Stage IV Cancer in Singapore. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;20:20-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Evans R, Finucane A, Vanhegan L, et al. Do place-of-death preferences for patients receiving specialist palliative care change over time? Int J Palliat Nurs 2014;20:579-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali M, Capel M, Jones G, et al. The importance of identifying preferred place of death. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:84-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stajduhar KI, Allan DE, Cohen SR, et al. Preferences for location of death of seriously ill hospitalized patients: perspectives from Canadian patients and their family caregivers. Palliat Med 2008;22:85-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas C, Morris SM, Clark D. Place of death: preferences among cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:2431-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tay RY, Choo RWK, Ong WY, et al. Predictors of the final place of care of patients with advanced cancer receiving integrated home-based palliative care: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Palliat Care 2021;20:164. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prioleau PG, Soones TN, Ornstein K, et al. Predictors of Place of Death of Individuals in a Home-Based Primary and Palliative Care Program. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:2317-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan WS, Bajpai R, Low CK, et al. Individual, clinical and system factors associated with the place of death: A linked national database study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0215566. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teo I, Singh R, Malhotra C, et al. Cost of Medical Care of Patients with Advanced Serious Illness in Singapore (COMPASS): prospective cohort study protocol. BMC Cancer 2018;18:459. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malhotra C, Harding R, Teo I, et al. Financial difficulties are associated with greater total pain and suffering among patients with advanced cancer: results from the COMPASS study. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:3781-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lyons KD, Bakitas M, Hegel MT, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Palliative care (FACIT-Pal) scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37:23-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henriksson A, Andershed B, Benzein E, et al. Adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Preparedness for Caregiving Scale, Caregiver Competence Scale and Rewards of Caregiving Scale in a sample of Swedish family members of patients with life-threatening illness. Palliat Med 2012;26:930-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beck KR, Tan SM, Lum SS, et al. Validation of the emotion thermometers and hospital anxiety and depression scales in Singapore: Screening cancer patients for distress, anxiety and depression. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2016;12:e241-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malhotra R, Chan A, Malhotra C, et al. Validity and reliability of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment scale among primary informal caregivers for older persons in Singapore. Aging Ment Health 2012;16:1004-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 2002;24:49-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pugh SL, Brown PD, Enserro D. Missing repeated measures data in clinical trials. Neurooncol Pract 2021;9:35-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang ST, Liu TW, Tsai CM, et al. Patient awareness of prognosis, patient-family caregiver congruence on the preferred place of death, and caregiving burden of families contribute to the quality of life for terminally ill cancer patients in Taiwan. Psychooncology 2008;17:1202-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiang JK, Kao YH. Quality of end-of-life care of home-based care with or without palliative services for patients with advanced illnesses. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e25841. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Badanta B, González-Cano-Caballero M, Suárez-Reina P, et al. How Does Confucianism Influence Health Behaviors, Health Outcomes and Medical Decisions? A Scoping Review. J Relig Health 2022;61:2679-725. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barben J, Billa O, Collot J, et al. Quality of life and perceived burden of the primary caregiver of patients aged 70 and over with cancer 5 years after initial treatment. Support Care Cancer 2023;31:147. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Birnie K, Speca M, Carlson LE. Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Stress Health 2010;26:359-71. [Crossref]

- Mulcahy Symmons S, Ryan K, Aoun SM, et al. Decision-making in palliative care: patient and family caregiver concordance and discordance-systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2023;13:374-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Foreman LM, Hunt RW, Luke CG, et al. Factors predictive of preferred place of death in the general population of South Australia. Palliat Med 2006;20:447-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ng HY, Griva K, Lim HA, et al. The burden of filial piety: A qualitative study on caregiving motivations amongst family caregivers of patients with cancer in Singapore. Psychol Health 2016;31:1293-310. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cai J, Zhang L, Guerriere D, et al. Where Do Cancer Patients in Receipt of Home-Based Palliative Care Prefer to Die and What Are the Determinants of a Preference for a Home Death? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;18:235. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen Q, Terhorst L, Geller DA, et al. Trajectories and predictors of stress and depressive symptoms in spousal and intimate partner cancer caregivers. J Psychosoc Oncol 2020;38:527-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin Y, Luo X, Li J, et al. The dyadic relationship of benefit finding and its impact on quality of life in colorectal cancer survivor and spousal caregiver couples. Support Care Cancer 2021;29:1477-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ornstein KA, Wolff JL, Bollens-Lund E, et al. Spousal Caregivers Are Caregiving Alone In The Last Years Of Life. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:964-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajaei A, Heshmati S, Giesemann X. Mindfulness in Patients with Cancer is Predictive of Their Partners’ Lowered Cancer-Related Distress: An Actor-Partner Interdependence Model of Spirituality and Mindfulness in Dyads Facing Cancer. Am J Fam Ther 2022;52:276-94. [Crossref]

- Lau JH, Abdin E, Jeyagurunathan A, et al. The association between caregiver burden, distress, psychiatric morbidity and healthcare utilization among persons with dementia in Singapore. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sato T, Fujisawa D, Arai D, et al. Trends of concerns from diagnosis in patients with advanced lung cancer and their family caregivers: A 2-year longitudinal study. Palliat Med 2021;35:943-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]