Prospective surveillance of patients after palliative radiation for painful bone metastases: a feasibility study

Highlight box

Key findings

• Patient calls following radiation therapy (RT) for painful metastases identified those who required further management who would otherwise have been missed. However, the associated workload was impracticable for current nursing workflow. Dedicated staffing or specialized roles may help with this.

What is known and what is new?

• It is known that RT can offer effective pain control for bony metastases.

• Patients engaged with nurse-led follow up of treatment, however staffing this was a challenge.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Further study is required to establish a balance between ensuring adequate follow up for pain management for palliative patients with staff workflow.

Introduction

Bone metastasis is the most common site and cause of cancer-related pain, present in about 50–70% of cancer patients (1). Radiation therapy (RT) can provide successful palliation of painful bone metastases that is time-efficient and associated with very few side effects (2,3). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for palliative care emphasize the importance of ongoing reassessment after palliative care interventions to optimize symptom management and quality of life (QOL), but there are currently no consensus guidelines for surveillance after palliative radiation (4).

Practice patterns vary, but oftentimes radiation oncologists function primarily as consultants when palliating patients, with ongoing surveillance being managed by medical oncologists and other referring providers. These providers can lack the specialty-specific knowledge to assess whether an area can be re-treated with radiation if symptoms recur (5).

Telephone-based and nurse-led surveillance programs to evaluate cancer pain and radiation-related toxicities have been successfully implemented and have demonstrated feasibility (6-8). However, this model has not been applied to capturing patients with new or recurrent pain needs after palliative radiation.

In this prospective feasibility trial, we aimed to determine if standardized surveillance after palliative radiation, performed by a radiation oncology nurse-physician collaborative team, may identify patients with recurrent pain. We hypothesized that more direct involvement of the radiation oncology team in surveillance may catch patients with an opportunity for improving symptom management. This, we predicted, may in turn lead to increased symptom control, reduced hospital admissions, and improved QOL. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-10/rc).

Methods

This single center study took place over a 12-week period at an academic hospital. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institute Review Board (No. 22-1024) and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Patients were identified through review of the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) who had at least one painful bone metastasis that was treated with conventional palliative radiation. The painful bone metastasis had to be associated with a worst pain score of at least 4, rated on a 0–10 scale, in the last 72 hours (9), and the pain must have been localized to a radiographically confirmed lesion. Patients had to have a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) of at least 50. Exclusion criteria included a self-reported non-cancer-related chronic pain syndrome, pain specialty care prior to cancer diagnosis, chronic opioid use (>90 days) prior to cancer diagnosis, or prior diagnosis or treatment of opiate use disorder or other substance use disorder or chronic opioid use.

Screening occurred using EMR and patients were identified for potential enrollment at the time of initial consultation.

Study design

Patient treatment took place in line with standard of care. All dates were calculated from day 0: the last day of their treatment. The initial call at week one of treatment was a standard-of-care call in line with departmental policy. However, this call was undertaken by study nurses using the study call format (Appendix 1). Sample size was informed by statistical analysis.

Information was preferentially obtained from the patient, but where necessary, data were also obtained from a family member or other caregiver, in line with International Consensus on Palliative Radiotherapy Endpoints (ICPRE) guidelines given the likelihood of declining performance status in this population (9). Furthermore, at any of the study calls, if the patient reported new or severe symptoms that required additional management, the radiation oncologist would be informed and appropriate referrals to urgent care settings would be made as needed. Calls were performed by each patient’s assigned nurse.

Calls were undertaken at week 4 to establish pain control. During the week 4 call, the following definitions were applied to the patient’s pain response, as defined by the ICPRE (9):

- Complete response (CR): a worst pain score of 0, rated on a 0–10 scale, with no associated increase oral morphine equivalent (OME) consumption.

- Partial response (PR): a reduction in the worst pain score of 2 points or more compared with baseline and no increase in daily OME consumption, or no increase in the worst pain score and a reduction in daily OME consumption of at least 25%.

- No pain response (NR): any other change in worst pain score and/or daily OME consumption not included in CR or PR.

- Pain recurrence: an increase in the worst pain score of 2 points or more compared with lowest pain score since the last point of contact, or no increase in the worst pain score with an increase in daily OME consumption of at least 25%.

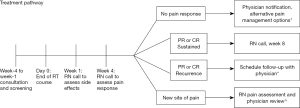

Patients followed the appropriate pathway for their pain response levels as in Figure 1.

Patients with a PR or CR were provided with departmental contact information and proceeded on to the week 8 call. Patients with NR were referred back to their treating radiation oncologist via EMR, where alternative pain management options were discussed, including additional drug management, re-irradiation, surgical management or referral to hospice services. These patients did not receive a week 8 call. New sites of pain were assessed by the nursing team, and then referred back to their radiation oncologist. These patients did not receive a call at week 8.

This process was repeated at week 8 for the remaining patients. Those with a sustained PR or CR finished the study and were provided with department contact information for future use. Those who had experienced a recurrence of pain were referred to their radiation oncologist, as were those with a new site of pain. An 8-week study period was chosen to allow for resolution of RT related side effects on the treated site, whilst acknowledging the advanced nature of disease progression for these patients.

Statistical analysis

The patient response to each call was assessed as a binary variable (yes or no) after up to 2 attempted calls. For each time point, the patient response rate was calculated as the number of patients responding at that time point over the total number of patients enrolled. Considering prior literature (6-8) and drop-off due to patient survival, the protocol was considered feasible if the response rate was ≥50% at week 8. Feasibility was also characterized by the following response rate goals: ≥67% at week 1 and week 4, and ≥50% at week 8. The rate of completion of surveys at each time point was analyzed separately, as some patients may answer the nurse call but decline to complete the surveys. However, the same goals for survey completion rate were used to assess feasibility. The nurse’s adherence to the protocol timeline were considered feasible if ≥90% of calls were done within 3 business days of the target date.

Overall survival was calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method. The worst pain score, rated on a 0–10 scale, in the last 72 hours was be recorded for each patient at each time point, and median and interquartile range (IQR) at each time point was calculated and plotted over time. Opioid use was calculated at each time point and recorded as OME.

The EORTC-QLQ-BM22 survey was administered to assess QOL. Rate of hospital admission for cancer-related pain, and the number of days of health care system contact related to pain management was calculated for each patient at the end of the study period, and each was analyzed as a median and IQR.

Descriptive measures of feasibility were collected from study team members on an ongoing basis to assess study logistics and optimize intervention delivery. These measures included:

- Success of screening for eligible patients.

- Ability of the nurse to assess pain and make protocol-informed recommendations over telephone calls.

- Ability of nurse and physician to collaborate on addressing persistent, new, or recurrent sites of pain.

- Nurse satisfaction with the protocol.

Results

For feasibility analysis, twenty patients were initially identified as eligible to participate in the trial and consented. These patients were referred to Radiation Oncology for an acute pain crisis over a period of two months in 2023, from both outpatient and inpatient oncology services. Of these patients, 14 participants completed treatment and their initial week 1 calls. Patients who transitioned to hospice care (4 patients) and those who died (2 patients) prior to the week one calls were excluded. The 14 eligible patients were evenly split between male and female, with a range of primary diagnoses (Table 1).

Table 1

| Patient demographics | Value, n=14 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 (50%) |

| Female | 7 (50%) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 3 (21%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 11 (79%) |

| White | 7 (50%) |

| Black | 2 (14%) |

| Asian | 2 (14%) |

| Other | 3 (21%) |

| Primary disease | |

| Prostate | 4 (29%) |

| Breast | 2 (14%) |

| Colon | 1 (7%) |

| Pancreatic | 1 (7%) |

| Renal cell | 2 (14%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 (7%) |

| Gynaecological | 1 (7%) |

| Lung | 2 (14%) |

| Primary insurance | |

| Medicaid | 8 (57%) |

| Private | 4 (29%) |

| Veterans administration | 1 (7%) |

| None | 1 (7%) |

Patient pain and opioid use

At time of consent, the median pain score of all patients was 9.5 (IQR: 7.2–10.0), with an OME dose of 28.8 mg (IQR: 0.0–132.0 mg). At the week 1 call, the median pain score was 4.0 (IQR: 0.5–5.5). This increased slightly at week 4, with a median pain score of 5.0 (IQR: 1.2–8.8), however the median pain score at week 8 was 1.0 (IQR: 0.8–1.2). Median OME use dropped to 15 mg (IQR: 0.0–82.5 mg) at the week 4 call, however at week 8 had increased to 52.5 mg (IQR: 16.9–103.1 mg) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Patient outcome | Week 0 (n=14) | Week 1 (n=14) | Week 4 (n=13) | Week 8 (n=6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients referred | ||||

| Back to RT | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Deceased | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hospice | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Responded to call | ||||

| No | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Yes | 0 | 11 | 10 | 5 |

| Pain scores | 9.5 (7.2–10.0) | 4.0 (0.5–5.5) | 5.0 (1.2–8.8) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) |

| Opioid use (mg) | 28.8 (0.0–132.0) | NA | 15 (0.0–82.5) | 52.5 (16.9–103.1) |

Data are presented as number or median (IQR). RT, radiation therapy; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

Call response rates

Eleven patients (85%) responded to their week 1 call, with 83% (n=10) responding to their week 4 call and 83% (n=5) responding to their week 8 call (Table 2).

Patient outcomes

During the 8-week study window, 5 patients (42%) experienced a ‘pain flare’ (defined as an increase in pain score by 2 or more points compared to previous score, or no increase in pain score but with an increase of daily OME use by at least 25%) compared to 7 who did not. However, only 1 patient (8%) had a hospital admission for pain control, and the median number of days of healthcare contact for pain was 0 (IQR: 0–2) days. A total of 6 of the 14 patients were referred to their treating radiation oncologist for pain recurrence, and no patients were referred for new pain. At the end of the study period, five patients had died.

EORTC-QLQ-BM22

The EORTC-QLQ-BM22 questionnaire was given at the calls for week 4 and week 8. These questionnaires showed a reduction in overall scores for the Symptomatic scales between week 4 and week 8, with ‘painful sites’ moving from a median score of 20 (IQR: 13.3–33.3) to a median score of 3.3 (IQR: 0–21.7) and ‘pain characteristics’ moving from a median score of 22.2 (IQR: 11.1–33.3) to 11.1 (IQR: 11.1–11.1) (Figure 2). However, there were increases in the Functional Scales over the 4-week interval between the two calls. Functional interference went from a median of 55.6 (IQR: 38.9–61.1) to a median of 92.9 (IQR: 74–100) points, while Psychosocial aspects increased from a median of 55.6 (IQR: 38.9–61.1) to 61.1 (IQR: 38.9–84.7) points, highlighting the progression of incurable disease (Figure 2).

Nursing feasibility

Screening for potential candidates and enrollment of patients on the protocol was completed within 8 weeks, 4 weeks earlier than the anticipated completion time. No patients decided against enrolling, and no patients asked to be removed from the protocol during the study period.

Overall, nursing calls were made within 3 business days of the anticipated date 63% of the time (Table 3). The highest percentage of calls taking place within the time frame was the week 1 call, at 82% (n=9).

Table 3

| Nurse feasibility measure | Week call made | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 4 | Week 8 | Median | |

| Total calls answered | 11 | 9 | 5 | – |

| Calls made within 3 days | 9 (82%) | 6 (67%) | 2 (40%) | 63% |

| Median time of call (mins) | 10 | 17 | 20 | 16 |

| Interpreted calls (mins) | 31 | 42 | 34 | 36 |

| Non-interpreted calls (mins) | 8 | 15 | 18 | 14 |

The median time of each call was 16 minutes, with the week 1 call (with fewer questions) the shortest median at 10 minutes, the week 4 call at 14 minutes and the final call at a median of 20 minutes. The contents of the call at week 4 and week 8 were identical. There was a large discrepancy in the median time of calls where an interpreter (n=2) was required and those calls where no interpreter was required (n=12). Calls requiring an interpreter were a median of 36 minutes long compared to 14 minutes for patients who did not require interpretation services (Table 3).

Qualitative feedback

Ultimately, the nursing staff who participated in this feasibility study felt that the study was too great a time burden on them. Additionally, “It felt like we were being put in the position to ask about problems that we couldn’t solve, or that we became the verbal punching bag about parking, availability and whatever the patient was upset about.” Nurses felt that patients often did not understand the difference between a call specifically to address their bony metastatic pain and generally to ask how they were doing.

Discussion

While there are limitations in this study due to its small sample size and the short duration of the study, the overall results show that from the patients perspective, enhanced palliative surveillance is feasible. Patients answered calls and engaged with nursing staff at high levels, well above the feasibility goal of 67% to the last call. Patients were recruited easily, with the study meeting recruitment goals early and no withdrawals from the protocol.

Six patients who were identified as eligible and consented to the study were withdrawn prior to the week one call. The primary reasons for this were further progression of disease or death. In the case of further progression, these patients were transitioned to end of life care. RT is not given once a patient has entered hospice services, and as such additional calls were felt to be unnecessary.

The decrease in the median points in the symptomatic scales of the EORTC-QLQ-BM22, alongside the median decrease in pain scores shows there is an important role for radiation oncology in treating metastatic bony pain in improving quality of end-of-life. The increases in overall opioid use and increase in functional interference scores, as well as psycho-social aspects, highlights that symptomatic control exists alongside progression of disease, with a multi-disciplinary support required for patients.

Across all patients, there were only two outside healthcare visits associated with pain to untreated sites, showing a gap in current service. Six of the 14 patients were referred back to their radiation oncology provider for pain, with 4 of the 6 referrals taking place after the week 4 call, with a variety of outcomes from discussions of adherence to prescribed medications through to additional RT treatments. It may be appropriate in future studies to target calls around 4 weeks post-treatment. RT for ongoing pain should be a mainstay of end-of-life care, supporting symptom control with a non-curative intent.

In contrast, the feasibility measures from the nursing side were not met in any instance. Only 63% of calls were made within 3 business days of being due. The nursing team expressed concern over the length of time calls took when there was an interpreter involved. Non-English speaking patients may be less likely to receive the same standard of care as English-speaking patients. Significant changes would need to be made to this process to ensure healthcare inequalities are not exacerbated for a population who may already have poorer end-of-life healthcare outcomes (10).

Nursing shortages in post-coronavirus disease (COVID) healthcare have been well published (11,12), and issues of turnover and staffing shortages that made the burden of calls unfeasible for the nursing staff. Previous studies of nurse-led palliative care follow-up have been found these interventions to be feasible on both the patient and healthcare provider metrics, however no study has taken place in the post-COVID time period (6-8). While nursing continues to face these challenges, it may be more appropriate for a more specialized role, such as an Oncology Nurse Navigator to undertake these calls (13), which have considerable value to patients and can result in improved symptom management. A nurse navigator may also be able to address the concern that many of patients’ issues were not directly linked to their radiation treatment. Identifying an appropriate member of staff to follow up with palliative patients has potential to add value to both patients and departments of Radiation Oncology as a whole.

From a current staffing perspective, this intervention is not feasible, especially following COVID. This study points to an unmet need in palliative care need and identifies staffing feasibility as a rate limiting step. Importantly, it underscores the necessity of health care systems investment in nursing support as a key potential intervention to overcome these hurdles. This study also highlights the impact such nursing-driven surveillance has on patients’ palliative experience at end of life. Such nursing-driven intervention offers a process to identify patients who will benefit from further pain management and as such sets a platform to test the intervention in a larger scale trial, which are part of our ongoing efforts.

Conclusions

As all the patient feasibility measures were exceeded, along with patients requiring further pain management, there is a clear need for improved follow up after palliative RT for painful bone metastases. However, significant staffing challenges for this intervention must be overcome in order to scale this support. Future study may target follow up to the most appropriate patients to work around these staffing challenges. Particular care must be taken to ensure health equity, particularly for patients who do not speak English as a first language.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-10/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-10/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-10/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-10/coif). K.F. is the resident board member of the Society for Palliative Radiation Oncology. S.D.K. reports grants of 1R01DE028282-01, 1R01DE028529-01, 1P50CA261605-01, and 1R01CA284651-01; clinical trial funding from AstraZeneca, and Genentech; and Preclinical funding from Amgen, and Roche. She also reports honoraria at academic institutions and support from AHNS, ASTRO, AACR, and ImmunoRads for attending the meeting. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement:

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- McDonald R, Chow E, Rowbottom L, et al. Quality of life after palliative radiotherapy in bone metastases: A literature review. J Bone Oncol 2014;4:24-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chow E, Harris K, Fan G, et al. Palliative radiotherapy trials for bone metastases: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1423-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lutz S, Berk L, Chang E, et al. Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: an ASTRO evidence-based guideline. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;79:965-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2022). Adult Cancer Pain (version 1.2022). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pain.pdf

- Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Bair MJ. Pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a synthesis of recommendations from systematic reviews. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:206-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chow E, Fung KW, Bradley N, et al. Review of telephone follow-up experience at the Rapid Response Radiotherapy Program. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:549-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Given B, Given CW, McCorkle R, et al. Pain and fatigue management: results of a nursing randomized clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum 2002;29:949-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haddad P, Wilson P, Wong R, et al. The success of data collection in the palliative setting--telephone or clinic follow-up?. Support Care Cancer 2003;11:555-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chow E, Hoskin P, Mitera G, et al. Update of the international consensus on palliative radiotherapy endpoints for future clinical trials in bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:1730-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silva MD, Genoff M, Zaballa A, et al. Interpreting at the End of Life: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Interpreters on the Delivery of Palliative Care Services to Cancer Patients With Limited English Proficiency. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:569-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tamata AT, Mohammadnezhad M. A systematic review study on the factors affecting shortage of nursing workforce in the hospitals. Nurs Open 2023;10:1247-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanford K. Nursing 2023: A New Emphasis on Nursing Strategy. Nurs Adm Q 2023;47:289-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yackzan S, Stanifer S, Barker S, et al. Outcome Measurement: Patient Satisfaction Scores and Contact With Oncology Nurse Navigators. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2019;23:76-81. [PubMed]