Patient versus health care provider perspectives on spirituality and spiritual care: the potential to miss the moment

Introduction

The provision of spiritual care, especially at end of life, is seen as vitally important in the provision of quality care. Spiritual pain felt by patients and family members impacts on many aspects of the illness experience including physical and emotional symptoms, social relationships, and quality of life (1-5).

The World Health Organization has identified spiritual care as a core domain in patient care and evidence based national standards on palliative care emphasize the necessity of providing spiritual care (6-8). Yet a variety of authors have described unmet needs regarding spiritual care, despite the strong support for the presence of existential distress and suffering in patients with life threatening conditions (8-14).

Meeting the spiritual care needs of patients and family members necessitates all health care providers have some degree of proficiency in this domain (11,15,16). However, front line practitioners have expressed difficulty recognizing spiritual distress, engaging in discussions about spirituality with patients or family members, and being clear about their role in providing spiritual care (17,18). Additionally, busy clinical environments contribute to the challenge with increasing patient workloads and shortened intervals with individual patients. Although the recognition and acknowledgement of spiritual distress in an individual is a key step in providing spiritual care, it is a challenging process in itself (10,19).

Our work began with a focus on identifying whether there was a screening question or questions that would allow the front line worker to reliably and validly identify spiritual distress in an individual with a life threatening condition. The work unfolded in two stages: interviews with patients with advanced illnesses, and interviews with health care providers caring for this patient population. This article will focus on comparing the perspectives on spirituality and spiritual care from these two sets of interviewees with the subsequent implications for clinical practice.

Methods

Data collection

This study was conducted at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (SHSC), a tertiary care hospital in Toronto, Canada between March and November 2014. Patients with advanced disease and a prognosis of less than 12 months were eligible for inclusion and were recruited from the outpatient palliative care clinic, inpatient acute care wards and the palliative care unit. Eligible HCPs included licensed physicians, nurses or social workers who routinely cared for patients with advanced life-limiting illnesses. Physicians and nurses were individually invited to participate, while social workers were invited during a routine team meeting. Consenting participants engaged in an in-depth semi-structured interview by an experienced interviewer. Separate patient and HCP interview guides were developed and used to explore participant’s views on spirituality, spiritual distress and spiritual care. All interviews were audio-taped and later transcribed verbatim. This study was approved by the SHSC research ethics board (No. 439-2013), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Interview guide

The interview guides were developed by the research team to explore participant perspectives on spiritual distress. Questions were chosen to elicit participant views of spirituality, experiences with spiritual distress and spiritual care, and to provide insight into approaches and questions that might be used to identify/address spiritual distress. The research team reviewed the guides after the first several interviews to ensure the content elicited matched the goals of the study.

Qualitative analysis

The verbatim transcripts were subjected to a qualitative descriptive analysis (20) with patient and HCP transcripts initially analyzed separately. For each group, members of the research team read through several transcripts making margin notes about the content and subsequently agreed upon a list of topics or content categories for coding. All transcripts were then entered into NVivo9 (QSR International) software and coded by one individual using this agreed upon coding framework. The HCP transcripts were further analyzed by three authors (D Selby, D Seccaraccia, M Fitch) and the patient transcripts by five authors (D Selby, D Seccaraccia, M Fitch, J Huth, K Kurppa). Within the key domains identified, clear areas of commonality and difference emerged between patient and HCP responses with implications for clinical practice. Subsequent discussion among the investigators, comparing and contrasting their independent observations, resulted in the identification of themes within 4 major topic areas where HCPs and patients appeared to have important areas of both agreement and disagreement in responses: “Definition of spirituality”, “Definition of spiritual distress”, “Definition of spiritual care”, and “Screening process”. This paper reports on these areas of concordance and discordance.

Results

Healthcare providers

In total 21 healthcare professionals participated in the study, including 8 physicians, 7 registered nurses, and 6 social workers. Nurses, physicians and social workers worked in inpatient and outpatient settings in oncology, internal medicine and palliative care. Participants had a minimum of one-year experience working with people with advanced end-of-life illness, but the majority had in excess of 5 years’ experience. The majority of healthcare providers were female.

Patients

Twenty-three patients were approached, of whom 16 ultimately participated in the study (3 refused, 2 were too unwell and 2 died prior to the interview). Eligible patients had a diagnosis of a significant, advanced illness and a prognosis of less than 12 months as determined by the palliative care consultant providing regular care.

Topics

Topic 1: definition of spirituality

HCP’s and patients had areas of commonality in their definitions of spirituality but also areas of significant contrast. Both groups spoke of spirituality as being unique to each individual and including personal values and beliefs. Both also identified formal religious beliefs as an important component of spirituality though recognized that spirituality could exist outside of a formal religion. HCPs were more likely to describe these as clearly dichotomous groups whereas patients tended to flow back and forth more readily between ‘religion’ and ‘spirituality’ as if they existed as a continuum.

In reviewing the transcripts, one of the most notable findings was the relative ease patients had in describing spirituality whereas the HCP’s often struggled to express their thoughts, though clearly acknowledging the importance of spirituality. Further, patients repeatedly referred to their senses as they described spirituality, covering all of taste, touch, smell, sight and hearing, whereas this was not mentioned by any HCP. Patients frequently referred to ‘living in the moment’ and appreciating the immediate, small things in life as part of their spirituality, which they acknowledged as having developed over the time of their illness. In contrast, HCP’s had a greater focus on spirituality as finding meaning, making sense, or finding purpose, which was strikingly less common in the patient descriptions (Table 1).

Full table

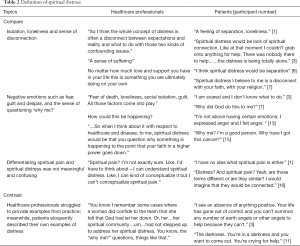

Topic 2: definition of spiritual distress

Patients and HCP’s had more areas of concordance when describing spiritual distress. Both groups described spiritual distress in terms of words such as isolation, loneliness and a sense of disconnection. For both, these terms related to their relationship with others around them (e.g., family) as well as their religion (i.e., disconnected from God). Negative emotions such as fear, guilt and despair were also used by both groups, as was the sense of questioning ‘why me’. Not surprisingly, HCPs tended to speak more to visibly detectable behaviors such as questioning and emoting, while patients described internal, experiential distress often with a focus on powerlessness and a lack of control. Patients had no difficulty providing rich examples of spiritual distress while HCP’s struggled to identify specific examples from their practice. Neither group found differentiating spiritual pain and spiritual distress to be meaningful and most replied with confusion when asked about the difference, tending to say pain was perhaps more intense (Table 2).

Full table

Topic 3: definition of spiritual care

In discussing spiritual care patients and HCP’s again had areas of both concordance and discordance.

Concordant concepts included the key aspect of listening and being ‘with’ the patient, which HCP’s often referred to as ‘whole person care’. Both referred to the sense of someone ‘taking on’ the burden for the patient and both highlighted the importance of family as critical for spiritual care. For each group formal religion and the comfort it provided was also identified as important.

Areas of difference largely focused on who should provide spiritual care. HCP’s, while acknowledging its importance, only rarely saw spiritual care as within their domain, for reasons related to expertise, comfort and practical concerns such as time. The almost uniform response from HCP’s was to refer to chaplaincy, though some did mention the importance of calling on family. Patients, on the other hand, were quite broad in their thoughts of who provided spiritual care, having it encompass anyone with whom they felt heard and understood, which in turn, left them with the sense of connection, otherwise missing in spiritual distress. The importance of ‘feeling connected’ was highlighted significantly more by patients than HCP’s in their descriptions. Interestingly, some patients did note they were not sure if they would be comfortable with their health care providers asking about spiritual issues, noting that this required a sense of relationship as a first step (Table 3).

Full table

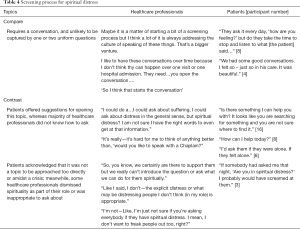

Topic 4: screening process for spiritual distress

Healthcare professionals and patients were in agreement that the screening process is one that requires a conversation and is unlikely to be captured by one or two simple, uniform questions. While patients offered a number of suggestions for opening the topic they also acknowledged that the time and situation needed to be appropriate. Patients were not sure it was a topic that could be approached too directly and some noted that amidst a crisis was likely not the right time. HCP’s tended to focus more on whether identification of spiritual distress was even within their domain of care (Table 4).

Full table

Discussion

Spiritual care is well recognized as an important component of patient care particularly for those with advanced illness (2,5,11,21,22). To provide such care, however, it is important that we understand both patient and HCP perspectives on spirituality and spiritual distress and how these perspectives both align and differ. This study was originally designed to develop a screening question to allow ready identification of spiritual distress by front line HCP’s but what emerged instead, was a number of important areas of concordance and discordance in how patients and HCP’s viewed both spirituality and the care of spiritual distress.

Interesting areas of contrast were notable in definitions of spirituality with patients highly focused on sensory experiences and living ‘in the moment’ rather than limiting spirituality to belief systems and ‘answers’, though certainly patients spoke of a connection to a higher being and for many that was indeed an important component of spirituality. This focus on sensory experiences as a core component of spirituality was more prominent in our study than has been described in prior studies, which have highlighted to a greater extent the focus on meaning making described by patients. However, in her review of spirituality, Hermann (12) listed ‘need to experience nature’ (page 71) as one of the six facets of spirituality patients described. Similarly, Edwards meta-analysis (11) identified ‘relationship with nature and music’ (page 759) as one of the relationships patients described as important. In general, our HCP’s, unlike patients, struggled to easily define spirituality, though uniformly cited its importance, a finding consistent with prior literature (11,17). When defining spiritual distress, HCP’s and patients were quite aligned in their focus on suffering, isolation, and questioning ‘why’. However, while patients had a broad sense of provision of spiritual care, essentially including anyone with whom they felt connected and supported, HCP’s were generally uncomfortable with the thought of providing spiritual care and consistently described this as belonging in the domain of chaplaincy. Neither group felt there was an easy or quick way to screen for spiritual distress.

These data raise the possibility of significant ‘misses’ occurring in interactions between patients and HCP’s, where patients may not feel heard or understood despite the best intentions of the HCP.

The first source of these potential misses lies in the consistent response from HCP’s that spiritual care was simply not their role. Again despite the clear acknowledgment of the importance of spiritual care, virtually all HCP’s spoke of spiritual care lying predominantly in the domain of chaplaincy. Kalish et al. (23) in a review of the literature noted that HCP’s tended to view spiritual care as part of their role to a much greater extent than they actually provided, somewhat in contrast to our findings where our participants acknowledged discomfort or inability to actually provide such care. Most expressed barriers including training, expertise, time and comfort with assessing for spiritual distress and providing spiritual care. Given patients expectations that any HCP can provide spiritual care by listening closely, attentively, and with a view to understanding the individual as a unique person and what was important to him or her, the fact that HCP’s largely rejected this as their role presents an overwhelming risk of a ‘miss’ or disconnect.

The second clear ‘miss’ lies in the fundamental difficulty HCPs had in expressing concepts around spirituality. Lacking a clear concept of spirituality, or a clear sense of what might be embraced by individuals as a spiritual experience, HCPs may then fail to ‘hear’ when a patient is expressing their sense of spirituality. For example, patients focused on events occurring in the moment and sensory experiences such as ‘smell the lilacs’ or ‘listening finely to the birds’ that the HCP may simply not categorize or appreciate as a spiritual expression by the patient. This in turn, may result in the HCP missing an opportunity to explore spirituality with their patient or to understand if there is a sense of spiritual distress being experienced by the individual.

Finally, the third identified potential for a miss may occur when the HCP who is wanting or willing to provide spiritual care approaches it with a pre-conceived idea or agenda about what spiritual care is. HCP’s, in discussing spirituality and spiritual care, often spoke of meaning making and finding purpose, a concept seldom actually expressed by patients. Despite good intentions, if HCP’s approach a patient with this pre-formed concept of what spiritual care is supposed to be or what elements ought to be covered in an assessment of spiritual needs, there is the risk that the patient may instead feel dismissed or ‘not heard’ while the HCP may feel frustrated that their efforts are not successful. The sense of alienation and isolation can then grow, worsening the disconnect.

Patients very clearly focused on internal experiential feelings, be they deep feelings of distress or important feelings of comfort by seemingly small, in the moment, sensory experiences. Provision of spiritual care as defined by both patients and HCPs, did include listening and being with the patient. HCP’s though, with their bias towards problem solving and ‘fixing, may be at risk of failing to hear the patient in a way that is meaningful and comforting. Active listening has been well described in the literature (21,24-27) as an effective tool to help patients in distress. Such listening implies being guided by the patient and acknowledging whatever feels important to them, without imposing pre-existing beliefs or having an agenda as to what the HCP views as important. As emphasized by Lemay et al. (28) ‘the value of listening, and the use of silence, while withholding ones theoretical assumptions and personal experiences...’ can allow ‘for connection and dialogue to emerge’ (page 488). Similarly, dignity therapy as described by Chochinov (29) encourages patients to express what is important to them. Puchalski (21) highlights in the report on a consensus conference the importance of HCP’s listening to the patients’ story, a concept further reinforced in Edwards meta-analysis of spiritual care (11). These approaches would all lessen the risk of any of the three described misses, as all assume spiritual care as in the domain of any provider who can be attentive, listen without an agenda, and ‘be with’ the patient.

Conclusions

Our study strongly reinforces the need to listen openly, being guided by the patient, to allow them to explore what is important to them, which in turn may help to alleviate their spiritual distress. While HCP’s uniformly acknowledge the importance of spirituality and addressing distress, it is important that they not impose their own preconceived notions of what ‘needs discussing’ (e.g., meaning making, finding a purpose, answering why) but rather allow the patient to lead the way.

Limitations

This study was limited to English speaking patients well enough to participate in an interview. All HCP’s were drawn from a single institution, and one with a strong chaplaincy program which may have influenced their perception of both their role and chaplaincy’s central role in spiritual care. Both factors will limit generalizability.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center’s Practice Based Research Award.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study was approved by the SHSC research ethics board (No. 439-2013), and all participants provided written informed consent.

References

- Delgado-Guay MO, Hui D, Parsons HA, et al. Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:986-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kandasamy A, Chaturvedi SK, Desai G. Spirituality, distress, depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Indian J Cancer 2011;48:55-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lethborg C, Aranda S, Cox S, et al. To what extent does meaning mediate adaptation to cancer? The relationship between physical suffering, meaning in life, and connection to others in adjustment to cancer. Palliat Support Care 2007;5:377-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boston PH, Mount BM. The caregiver's perspective on existential and spiritual distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;32:13-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boston P, Bruce A, Schreiber R. Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: an integrated literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:604-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Palliative care: Symptom management and end of life care. Integrated management of adolescent and adult illness. 2004. Available online: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/imai/genericpalliativecare082004.pdf, accessed May 1, 2016.

- National Consensus Project. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project, 2013.

- The Joint Commission. Spirituality, religion, beliefs, and cultural diversity. In: JCAHO’s Standards/Elements of Performance. Manual for Hospitals. Edition, 2013:PC. 02.02.13. Available online: http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/jcahorefs.pdf

- Mako C, Galek K, Poppito SR. Spiritual pain among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1106-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lunder U, Furlan M, Simonič A. Spiritual needs assessments and measurements. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2011;5:273-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, et al. The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med 2010;24:753-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hermann CP. Spiritual needs of dying patients: a qualitative study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001;28:67-72. [PubMed]

- Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol 2012;23 Suppl 3:49-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: a prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med 2004;18:39-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrell B, Otis-Green S, Economou D. Spirituality in cancer care at the end of life. Cancer J 2013;19:431-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sinclair S, Chochinov HM. The role of chaplains within oncology interdisciplinary teams. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:259-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Enzinger AC, et al. Nurse and physician barriers to spiritual care provision at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:400-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Selby D, Seccaraccia D, Huth J, et al. A Qualitative Analysis of a Healthcare Professional's Understanding and Approach to Management of Spiritual Distress in an Acute Care Setting. J Palliat Med 2016;19:1197-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baile WF, Palmer JL, Bruera E, et al. Assessment of palliative care cancer patients' most important concerns. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:475-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thorne S. Focus on qualitative methods. Interpretive description: a non-categorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Research in Nursing & Health 1997;20:169-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, de la Cruz M, Thorney S, et al. The frequency and correlates of spiritual distress among patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2011;28:264-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalish N. Evidence-based spiritual care: a literature review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:242-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dean M, Street RL Jr. A 3-stage model of patient-centered communication for addressing cancer patients' emotional distress. Patient Educ Couns 2014;94:143-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fassaert T, van Dulmen S, Schellevis F, et al. Active listening in medical consultations: development of the Active Listening Observation Scale (ALOS-global). Patient Educ Couns 2007;68:258-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McBrien B. Nurses' provision of spiritual care in the emergency setting--an Irish perspective. Int Emerg Nurs 2010;18:119-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Razavi D, Delvaux N. Communication skills and psychological training in oncology. Eur J Cancer 1997;33 Suppl 6:S15-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LeMay K, Wilson KG. Treatment of existential distress in life threatening illness: a review of manualized interventions. Clin Psychol Rev 2008;28:472-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:753-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]