Editor’s note:

“Palliative Radiotherapy Column” features articles emphasizing the critical role of radiotherapy in palliative care. Chairs to the columns are Dr. Edward L. W. Chow from Odette Cancer Centre, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto and Dr. Stephen Lutz from Blanchard Valley Regional Cancer Center in Findlay, gathering a group of promising researchers in the field to make it an excellent column. The column includes original research manuscripts and timely review articles and perspectives relating to palliative radiotherapy, editorials and commentaries on recently published trials and studies.

Collaboration between primary care physicians and radiation oncologists

Introduction

The cancer journey incorporates the diagnosis, workup and investigation of disease, implementing the treatment plan, and follow-up care. Physician communication can be in the form of traditional letters, telephone conversations and online communication via email or electronic patient records.

Patients are typically referred to a radiation oncologist once the cancer diagnosis has been established, from a medical oncologist, surgeon or internist. Treatment goals are established and radiation treatment plan devised. The radiation oncologist will follow the patient through treatment, monitoring the progress and managing the acute side effects of treatment. After treatment completion, follow-up care may be provided by the oncologist, other specialists, and/or the primary care physician (PCP).

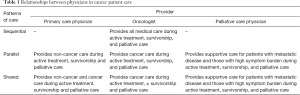

Three patterns of medical care representing increasing levels of involvement by the PCP have been identified (1).

- Sequential care where the patient receives all medical care from the oncologist(s) after diagnosis;

- Parallel care where the oncologist is responsible for cancer care and the PCP manages other medical issues;

- Shared care where the PCP and specialist are both involved in cancer care.

Shared or parallel care can help ease the transition of primary care from oncologist back to the PCP.

PCP involvement in cancer care

It is important for patients to maintain continuity of care with their PCP while being seen at the cancer center. The PCP has often been involved in the patients’ care for a number of years, developing over that time a trusting relationship with the patient and family. The PCP often provides easier access, less traveling time, and more personalized care than a busy cancer center. Many cancer patients also value their PCP for emotional and family support, for providing primary medical care, and for coordinating care with other health care providers (1).

When receiving active cancer treatment, either systemic therapy or radiation, patients may not be followed closely by their PCP (2). While 80% of PCPs believe it is important to observe patients during this time (3), another survey found that only 43% of patients felt their PCP was involved in their follow-up care, and only 31% had a follow-up appointment scheduled (2). Cancer patients can lose contact with their PCPs because of patient or physician relocation, limited involvement with the PCP prior to the cancer diagnosis, distrust over delay in diagnosis, failure to perceive a need for the PCP, lack of PCP involvement in the hospital, and poor physician communication (1).

PCPs have identified lack of communication with the oncologist as a major concern in caring for cancer patients (4). PCP surveys found that other complaints include failure of the oncologist to assign them a specific role in follow-up care, difficulty contacting oncologists, letters from the oncologist not arriving in a timely fashion, and the letter content not being useful in patient management (4,5).

A short, semi-structured, interim consult report faxed to the referring physician and PCP immediately after consultation for palliative radiotherapy was found to be helpful in pain management (6). A standardized letter format devised to guide oncologists dictating notes to PCP after seeing palliative lung cancer patients at the Tom Baker Cancer Centre in Calgary, Alberta, was found to improve satisfaction with the information received (7).

Survivorship care

The NCI’s definition of a cancer survivor is “an individual is considered to be a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis, through the balance of his or her life”. Family members, friends, and caregivers are also impacted by the survivorship experience and are therefore included in this definition (8). For the purpose of this article, we will refer to the patient only when referring to “survivor”.

There has been a dramatic increase in the number of cancer survivors in the United States, from 3 million in 1971 to nearly 14.5 million in 2014 (9,10). This increase is due to rising incidence rates (from the aging population), earlier detection and better cancer treatment (11). A literature review in 2012 found at least 50% of survivors experience some late effects of cancer treatment (12). Symptom burden was consistent across the four most common types of cancer despite various treatments being delivered; with depression, pain and fatigue most commonly reported (13). Often overlooked and of importance for long term survivors is the higher incidence of second primary cancers, which is higher than the general population due to genetic susceptibilities, etiologic factors (smoking, excessive alcohol and obesity), and/or the mutagenic effects of cancer treatment (14). Appropriate risk adapted screening is required, and lifestyle modifications to reduce risks (smoking cessation, weight loss) should be encouraged (11).

Psychosocial effects of cancer and treatment can be profound, with both positive and negative effects reported by survivors (15). Distress can result from the fear of recurrence or death, with a minority of survivors meeting the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder. Returning to work, finances, issues regarding sexuality and fertility, are often of concern to patients and need to be addressed.

In 2005 the Institute of Medicine and National Research Council outlined four components of survivorship care (16). This included (I) prevention and detection of new cancers and recurrent cancer; (II) surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence, or second cancers; (III) intervention for consequences of cancer and its treatment; and (IV) coordination between specialists and primary care providers to ensure that all of the survivor’s health needs are met.

In September 2011 the LIVESTRONG Foundation expanded on this concept, stating all medical settings must provide for cancer survivors, either directly or through referral (17). This included (I) survivorship care plan, psychosocial care plan, and treatment summary; (II) screening for new cancers and surveillance for recurrence; (III) care coordination strategy that addresses care coordination with PCP and primary oncologist; (IV) health promotion education; and (V) symptom management and palliative care.

The importance of communication between oncologists and PCPs is highlighted in both reports. This in part led to the Commission on Cancer’s (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons accreditation standards for hospital cancer programs including development and implementation of a treatment summary and follow-up plan to patients who have completed cancer therapy (18). Physician communication requirements outlined in the 2016 ASTRO APEx (Accreditation Program for Excellence) plan include having a comprehensive patient evaluation documented prior to initiation of treatment, which should be sent to other involved health care providers including the PCP within four weeks. The post-treatment summary, which includes the pain management plan for patients with unresolved pain, and follow-up plan, should also be sent to other involved providers within four weeks (19). This underscores the importance being placed on survivorship care, and the role PCP play for this growing patient population.

Incorporating the PCP into oncology care

Various models have been proposed for providing survivorship care, having survivorship clinics within the cancer center, community survivorship clinics run by PCPs, and survivorship care in the primary care setting (20). As the number of cancer survivors grows, an increasing proportion of care will likely be performed by primary care teams. PCPs manage other chronic patient conditions and so are well equipped to assume routine follow-up care for cancer survivors. Table 1 summarizes the various physician relationships and ways patient care can be incorporated into these models. Breast and colorectal cancer survivors have also been found to have an increased number of visits with PCPs compared to non-cancer patients (21), which can increase physician workload but is also an opportunity to provide survivorship care. However, PCP education and guidelines for survivorship care are important, as PCPs may not know the health care needs of cancer survivors (22). With this goal in mind the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has devised a survivorship care plan template composed of the treatment summary and follow-up care plan to enhance communication and coordination of care for cancer survivors (23). Disease site specific guidelines are also available.

Full table

Long term follow-up care for the cancer survivor without active cancer issues in a busy cancer center by oncologists may not be ideal. For patients who are well and disease free, this is not cost effective and can prevent rapid access to oncology care for other cancer patients with active disease who need medical attention. Well patients can find attending the cancer clinic distressing, and the focus of visits is often not on providing the best evidence based survivorship care. Surveys of PCP have found they are willing to assume follow-up of cancer patients, and many feel they are better able to provide patients with psychosocial support (24).

However, patient surveys have reported that survivors want their oncologist involved in their follow-up care; often citing the belief their PCP lacked the expertise to deal with their cancer related issues (25). Physician surveys have also reported that the belief that patients would rather go to their oncologist for routine cancer care (3). However, two randomized trials in breast and colorectal patients found no difference in disease related outcomes, including survival, for survivorship care administered by PCP compared to oncologists (26,27). There also may be a difference in costs in the United States, as copays amounts differ between primary and specialist care.

A survey of Canadian PCPs was conducted to assess willingness and time from completion of active treatment they would prefer to assume exclusive follow-up care of cancer survivors (breast, prostate, colon and lymphoma) (24). This study reported that many PCP already provide exclusive care to well cancer survivors, especially beyond 5 years of diagnosis. Two thirds of PCPs were willing to assume exclusive follow-up care earlier, approximately 2.5 to 3.5 years after completion of active treatment. The most useful modalities to facilitate care included: (I) a patient-specific letter from the specialist; (II) printed guidelines; (III) expedited routes of re-referral, and expedited access to investigations for suspected recurrence.

This report served as the basis for developing a transition care clinic at the Odette Cancer Centre (OCC) for colorectal cancer and lymphoma patients. These patients are transitioned from the OCC back to their PCP for follow-up, assessment, and surveillance after completion of active treatment (28). Patients came for a single visit, and were seen by a family medicine physician and advanced practice nurse and received comprehensive survivorship care, individualized treatment summaries, and post-treatment care plans. An accompanying web resource connected patients to OCC after discharge and provided survivorship specific information. An eight-month pilot resulted in 66 patient visits and 28 discharges, with resource utilization savings of clinic visits and hospital CT scans. Symptom screening results across the domains of anxiety; depression, pain, and tiredness were on par with other cancer patients not being transitioned back to their PCP. Patient feedback indicated that those that found it difficult to attend OCC appointments appreciated knowing guidelines were available for their PCP and were comfortable with PCP follow-up, while patients whose PCP missed initial presenting symptoms preferred cancer centre “specialists” and were not comfortable with discharge.

Palliative care

Patients with non-curable disease, and treated with palliative intent for symptom management have somewhat different survivorship needs. These focus on pain and symptom management for themselves and their families. The PCP can play an important role in providing end of life care, and again excellent physician communication and collaboration is vital in ensuring optimal patient care. This population may include patient receiving palliative chemotherapy at the cancer center, and those off treatment but attending for assessment of cancer or treatment related symptoms.

The Rapid Response Radiotherapy Program (RRRP) at the Odette Cancer Centre provides prompt palliative radiotherapy to cancer patients with symptomatic locally advanced or metastatic disease (29). This population is routinely followed by their referring physician (usually medical oncologist) for continued oncologic care and do not routinely return to the RRRP for follow-up.

We surveyed this population to determine patients’ perception of PCP involvement in their care (30). Only 43% of patients felt their PCP was involved in their cancer care. The most common factor patients gave for perceiving limited PCP involvement was the medical oncologist looking after all their cancer needs. When asked if they wanted their PCP more involved in their cancer care, 22% of responders answered yes, 10% no, and 68% were satisfied with their current level of care. Sixty percent of patients had seen their PCP within the last month, however most (72%) patients did not have a future appointment scheduled with their PCP. Over 80% had seen their PCP since their cancer diagnosis. Eighty percent of patients reported they were satisfied with the overall medical care provided by their PCP. Patient perception of PCP involvement in their cancer care was significantly associated with time since last PCP visit, whether they had seen the PCP since their cancer diagnosis, if the PCP provided an on call service, and satisfaction with the overall medical care provided by the PCP.

PCP can maintain continuity of care with their patients through a model of shared or parallel care as patients pass through the cancer system. This can allow for easier transition of care back to the PCP once treatment at the cancer center has finished. For the population at the end-of-life, emergency room visits (31) and hospital deaths (32) have been shown to be decreased for cancer patients maintaining higher continuity of care with their PCP.

While most PCPs are willing to care for cancer patients at the end-of-life, a proportion may not want to, or feel comfortable with, providing palliative care (33). A palliative care team should then be consulted to assist with pain and symptom management. In 2012 ASCO released a Provisional Clinical Opinion recommending consideration of combined standard oncology care and palliative care early in the course of illness for any patient with metastatic cancer and/or high symptom burden to improve quality of life for both patients and care givers (34). Reports have shown that cancer patients experience a high symptom burden throughout their disease trajectory (35). Symptoms and needs were not routinely screened for and managed in cancer patients attending cancer clinic visits in the past. Therefore, in 2006 Ontario implemented Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) symptom screening for all outpatient visits to Regional Cancer Centers (36). The goal was to prompt earlier identification, documentation and communication of patients’ symptoms to improve the patients’ experience across the cancer journey. In a 2013 survey of 3,660 patients, 92% “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that the ESAS was important as it helped their healthcare team to know their symptoms and severity (37).

Conclusions

Collaboration and communication between oncologists and PCPs helps provide optimal care throughout a patient’s cancer journey. PCPs will play an important role in providing care for the growing population of cancer survivors. Providing physician education and survivorship care plans for patients can aid in transition of medical care back to the PCP upon discharge from the cancer center. For patients at the end-of-life, palliative care needs may be provided by the PCP and/or in consultation with a palliative care team.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Iype MO. Hemodynamic monitoring in the critically ill. Can Fam Physician 1982;28:2009-12. [PubMed]

- McWhinney IR, Hoddinott SN, Bass MJ, et al. Role of the family physician in the care of cancer patients. Can Fam Physician 1990;36:2183-6. [PubMed]

- Sangster JF, Gerace TM, Hoddinott SN. Family physicians' perspective of patient care at the london regional cancer clinic. Can Fam Physician 1987;33:71-4. [PubMed]

- Wood ML, McWilliam CL. Cancer in remission. Challenge in collaboration for family physicians and oncologists. Can Fam Physician 1996;42:899-904. [PubMed]

- Gilbert R, Willan AR, Richardson S, et al. Survey of family physicians: what is their role in cancer patient care? Can J Oncol 1994;4:285-90. [PubMed]

- Barnes EA, Chow E, Andersson L, et al. Communication with referring physicians in a palliative radiotherapy clinic. Support Care Cancer 2004;12:669-73. [PubMed]

- Braun TC, Hagen NA, Smith C, et al. Oncologists and family physicians. Using a standardized letter to improve communication. Can Fam Physician 2003;49:882-6. [PubMed]

- About Cancer Survivorship Research: Survivorship Definitions. The National Cancer Institute; 2014. Available online: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/statistics/definitions.html. Accessed May 11, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cancer survivors--United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:269-72. [PubMed]

- DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:252-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Survivorship (Version 1. 2016). Available online: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2016.

- Valdivieso M, Kujawa AM, Jones T, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: a review of the literature and a call to action. Int J Med Sci 2012;9:163-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, et al. It's not over when it's over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors--a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med 2010;40:163-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wood ME, Vogel V, Ng A, et al. Second malignant neoplasms: assessment and strategies for risk reduction. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3734-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bellizzi KM, Miller MF, Arora NK, et al. Positive and negative life changes experienced by survivors of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Behav Med 2007;34:188-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. editors. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2005.

- The Need for Consensus on Essential Elements of Survivorship Care Delivery. Available online: http://images.livestrong.org/downloads/flatfiles/what-we-do/our-approach/reports/ee/EssentialElementsBrief.pdf

- Cancer Program Standards (2016 Edition). Available online: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards

- American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology Accreditation Program for excellence, safety and quality for radiation oncology practice. 2016. Available online: https://www.astro.org/uploadedFiles/_MAIN_SITE/Daily_Practice/Accreditation/Content_Pieces/ProgramStandards.pdf

- Nekhlyudov L. Integrating primary care in cancer survivorship programs: models of care for a growing patient population. Oncologist 2014;19:579-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heins M, Schellevis F, Rijken M, et al. Determinants of increased primary health care use in cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4155-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians' and oncologists' knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1403-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology Survivorship Care Planning Tools. 2017. Available online: https://www.asco.org/practice-guidelines/cancer-care-initiatives/prevention-survivorship/survivorship/survivorship-12. Accessed May 11, 2016.

- Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, et al. Primary care physicians' views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3338-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hudson SV, Miller SM, Hemler J, et al. Adult cancer survivors discuss follow-up in primary care: 'not what i want, but maybe what i need'. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:418-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, et al. Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: a comparison of family physician versus specialist care. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:848-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wattchow DA, Weller DP, Esterman A, et al. General practice vs surgical-based follow-up for patients with colon cancer: randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 2006;94:1116-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deol R, Cheung MC, Del Giudice EM, et al. Transition care clinic: Evidence-based survivorship care. ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings 2013;31:141.

- Danjoux C, Szumacher E, Andersson L, et al. Palliative radiotherapy at Toronto–Sunnybrook regional cancer centre: the rapid response radiotherapy program. Curr Oncol 2000;7:52-56.

- Barnes EA, Fan G, Harris K, et al. Involvement of family physicians in the care of cancer patients seen in the palliative Rapid Response Radiotherapy Program. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5758-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burge F, Lawson B, Johnston G. Family physician continuity of care and emergency department use in end-of-life cancer care. Med Care 2003;41:992-1001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burge FI, Lawson B, Johnston G, et al. Health care restructuring and family physician care for those who died of cancer. BMC Fam Pract 2005;6:1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnes EA, Hanson J, Neumann CM, et al. Communication between primary care physicians and radiation oncologists regarding patients with cancer treated with palliative radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2902-7. [PubMed]

- Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:880-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vainio A, Auvinen A. Prevalence of symptoms among patients with advanced cancer: an international collaborative study. Symptom Prevalence Group. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12:3-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dudgeon D, King S, Howell D, et al. Cancer Care Ontario's experience with implementation of routine physical and psychological symptom distress screening. Psychooncology 2012;21:357-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cancer Care Ontario (CCO). Patient satisfaction survey. Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto (2013).