Active treatment at the end of life—importance of palliative care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a cohort study

Highlight box

Key findings

• Patients under 75 years old have a greater risk of receiving active treatment during the last 3 weeks of life.

• The greatest benefit of palliative care teams is obtained in patients with performance status measured by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scores 2 and 3.

• An assessment by multidisciplinary teams has a significant impact on the decision to not administer active treatment over the last 3 weeks of life of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

What is known and what is new?

• No consensus has been reached yet to decide the moment in which active treatment should be stopped and symptomatic control optimized. Suboptimal access to palliative care units is associated with greater aggressiveness in the use of active treatments and a lower quality of life for patients in the last stages of their disease.

• In advanced NSCLC, immunotherapy’s variable response and toxicity make it challenging to determine when to shift from active treatment to palliative care. The evaluation of patients with an ECOG >2 by palliative care units provides valuable insights into the appropriate timing for discontinuing active treatment in these cases.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• New markers should be sought that, in the era of immunotherapy, are useful for clinicians in the assessment and treatment decision in patients with advanced NSCLC.

Introduction

With 30,000 diagnosed cases and 23,300 deaths per year, lung cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer in Spain, and the first one in terms of mortality (1). A high percentage of patients will be diagnosed in advanced stages of the disease in which there is distant involvement (2) and there is a high burden of disease manifested by cough, pleural effusion, respiratory infections, etc. Each new case of lung cancer needs to be assessed by a multidisciplinary team. The choice of treatment is based on the tumor stage, its histology, the molecular markers and the general status of the patient, measured with the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale and/or the Karnofsky Performance Status Score (3). Although there are currently different scales and biomarkers that can help predict the clinical diagnosis, no consensus has been reached yet to decide the moment in which active treatment should be stopped and symptomatic control optimized (4). According to the indicator proposed by Earle et al., we may refer to “aggressiveness” in oncology when over 10% of the patients receive active treatment over the last 2 weeks of life (5). Suboptimal access to palliative care units is associated with greater aggressiveness in the use of active treatments and a lower quality of life for patients in the last stages of their disease (6). Palliative care focuses on improving the quality of life and comfort of patients in the final stages of their disease, and it attempts to provide relief for pain and other distressing symptoms by integrating physical, psychological, and spiritual aspects (7). It provides a support system that integrates a team of professionals composed of doctors, nurses, psychologists, and social workers, among others (5). Through personalized follow-up, focused on both the patient and their families, and addressing typical symptoms of lung cancer patients such as pain or dyspnea, while also tackling psychosocial and spiritual aspects, there is an improvement in quality of life in the final phase of the oncological disease. Palliative care is useful both when active treatment has been discontinued and also in combination with conventional chemotherapy (8,9). Despite the importance of palliative care in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (mNSCLC) management, the impact of palliative care on the administration of active treatment over the last weeks of life remains understudied. The main objective of this study is to assess the impact of palliative care on the administration of active treatment over the last 3 weeks of life of patients with mNSCLC and its impact on survival after the last cycle of treatment. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-97/rc).

Methods

Study design and patients

This is a retrospective study that includes patients from two hospitals (University Hospital of Salamanca and Montalvos Hospital) within the Salamanca University Hospital Complex, located in Salamanca, Castilla y León, Spain. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised 2013), ensuring respect for human rights, the safety, and the well-being of the participants. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Salamanca University Hospital Complex under approval number 2022-10-1155, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. It includes adult patients diagnosed with mNSCLC (stage IV) who had received, at least, a first-line of treatment with chemotherapy, either by itself or combined with immunotherapy between January 1, 2019, and April 30, 2024. Patients with druggable mutations that had specific treatment approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and/or European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the first line of treatment were excluded from the study. Patients with actionable mutations have more specific therapeutic options that are often less toxic than conventional first-line treatments with immunotherapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy. Additionally, these patients tend to be non-smokers or light former smokers, which means they have fewer comorbidities [such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)] associated with smoking. Moreover, patients with actionable mutations are usually younger, which is generally associated with a better functional status. In some cases, such as with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, there is a predominance of female patients. For all these reasons, given the demographic characteristics of the population we aim to study, we have decided not to include this type of patient in order to improve the quality of the study and ensure that the data obtained are reproducible across different populations. Data were collected on age, sex, smoking, histology, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, brain, and/or liver metastases, ECOG prior to the last cycle, palliative care assessment, place of death, cause of death, treatment administration in the last 3 weeks, overall survival (OS), line of treatment and agent used.

The palliative care assessment consisted of the patient receiving at least one home visit per month by the palliative care team which included a doctor, nurse, psychologist, and social worker. The goal of these visits was to manage symptomatic treatment, provide psychological support to help the patient and their family/caregivers cope with the terminal illness and assist in processing the economic aid provided by the government of Castilla y León to families with a member receiving palliative care. In addition to the in-person visits, weekly telephone contact was made with the patient or the primary caregiver to determine whether further in-person visits were necessary.

Furthermore, patients were provided with a specific phone number that gave them 24-hour access to the palliative care team in case they needed to discuss any issues or concerns.

Patients were considered to have been assessed by the palliative care team if they had received at least one visit by a palliative physician and a palliative nurse in the last 4 weeks.

Primary and secondary objectives

Primary objectives

Assessing the relationship between OS (in days) after the administration of the last cycle of treatment and the assessment by the palliative care unit in patients with mNSCLC.

Determining the influence of the assessment by the palliative care unit in the administration of active oncological treatment during the last 3 weeks of life of patients with mNSCLC.

Secondary objectives

Conducting a descriptive analysis of the epidemiological characteristics of the sample, including age, sex, tobacco consumption, histology (epidermoid and undifferentiated adenocarcinoma), PD-L1 expression, brain and liver involvement, cause of death, place of death, line of treatment, functional state according to the ECOG scale, referral to palliative care and administration of treatment during the last 3 weeks of life.

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis was conducted based on age (75 years old or older and younger than 75 years old), PD-L1 expression (high expression when PD-L1 ≥50% and low expression when PD-L1 <50%), line of treatment (first, second, and third or higher line) and ECOG score (0, 1, 2, or higher).

Statistical analysis

For the descriptive analysis, summary statistics were used that included the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The median and frequencies were compared with Student’s t-test and the Chi-squared test (or Fisher’s test when indicated). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the OS curves. A confidence interval (CI) of 95% was used (95% CI). The log-rank test was used due to its effectiveness in the assessment of differences in survival functions throughout the period of study, and because it is particularly sensitive to the differences in the end of the monitoring period. Breslow’s test was used due to its high sensitivity to detect differences in survival times at the beginning of the monitoring period.

A multivariate analysis was conducted with binary logistic regression to assess the association between the administration of active treatment during the last 3 weeks of life (dependent variable) and the referral to palliative care, expression of PD-L1, age, and sex. The multivariate analysis was performed with the Cox regression model to assess the influence of the variables referral to palliative care, PD-L1, OS, and type of treatment (immunotherapy ± chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy by itself) on the distance between the administration of the last cycle of treatment and death. The statistical analysis was carried out with the software SPSS v.28.

Results

Characteristics of the population of study

In total, 118 patients were included in the analysis. The mean age was 68 years, 18.6% of the patients were women, 82.2% were smokers, and 71.2% had been diagnosed with adenocarcinoma. Their functional status before the last cycle of treatment according to the ECOG scale was 0 in 4 patients (3.4%), 1 in 25 patients (21.2%), 2 in 60 patients (50.8%), and 3 in 28 patients (23.7%). Fifty-six patients (47.5%) were subject to joint monitoring that included the palliative care team.

OS was 6 months or longer in 60.2% of the patients in the sample: 75.0% among patients assessed by the palliative care team vs. 46.8% among patients who had not been assessed by the team (P=0.002). Thirty-one patients (26.3%) had received treatment during the last 3 weeks of life: 10.7% among patients assessed by the palliative care team vs. 40.3% among those who had not been assessed (P<0.001). With regard to the line of treatment in the last cycle, 57 patients (48.3%) were in their first line of treatment, 33.9% of the patients who had been included in the palliative care team vs. 61.3% for those who were not included (P=0.02). The rest of the characteristics of the population of study are included in Table 1.

Table 1

| Variables | Total samples (n=118) | Receive palliative care (n=56) | No palliative care (n=62) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median [range] | 68 [60.75–75] | 69.5 [63–76] | 68 [59–73] | 0.46 |

| Age (years), n (%) | 0.42 | |||

| ≥75 | 48 (40.7) | 25 (44.6) | 23 (37.1) | |

| <75 | 70 (59.3) | 31 (55.4) | 39 (62.9) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.06 | |||

| Man | 96 (81.4) | 50 (89.3) | 46 (74.2) | |

| Woman | 22 (18.6) | 6 (10.7) | 16 (25.8) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | 97 (82.2) | 49 (87.5) | 48 (77.4) | 0.33 |

| Histology, n (%) | 0.90 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 84 (71.2) | 40 (71.4) | 44 (71.0) | |

| Epidermoid | 22 (18.6) | 11 (19.6) | 11 (17.7) | |

| Undifferentiated | 12 (10.2) | 5 (8.9) | 7 (11.3) | |

| PD-L1 expression, n (%) | 0.25 | |||

| ≥50% | 40 (33.9) | 16 (28.6) | 24 (38.7) | |

| <50% | 78 (66.1) | 40 (71.4) | 38 (61.3) | |

| Brain metastases, n (%) | 17 (14.4) | 8 (14.3) | 9 (14.5) | 0.97 |

| Liver metastases, n (%) | 19 (16.1) | 11 (19.6) | 8 (12.9) | 0.31 |

| ECOG PS last cycle, n (%) | 0.11 | |||

| ECOG 0 | 4 (3.4) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (4.8) | |

| ECOG 1 | 25 (21.2) | 7 (12.5) | 18 (29.0) | |

| ECOG 2 | 60 (50.8) | 31 (55.4) | 29 (46.8) | |

| ECOG 3 | 28 (23.7) | 16 (28.6) | 12 (19.4) | |

| Not coded | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Palliative care, n (%) | N/A | |||

| Yes | 56 (47.5) | 56 (100.0) | N/A | |

| No | 62 (52.5) | N/A | 62 (100.0) | |

| Place of death, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Palliative care | 40 (33.9) | 38 (67.9) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Oncology | 48 (40.7) | 2 (3.6) | 46 (74.2) | |

| Address | 24 (20.3) | 15 (26.8) | 9 (14.5) | |

| Intensive care medicine | 5 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.1) | |

| Other centers | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cause of death, n (%) | 0.16 | |||

| Second to progression | 65 (55.1) | 36 (64.3) | 29 (46.8) | |

| Infection/sepsis | 16 (13.6) | 5 (8.9) | 11 (17.7) | |

| Thromboembolism | 5 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.1) | |

| AMI/tamponade | 5 (4.2) | 2 (3.6) | 3 (4.8) | |

| Brain metastases | 14 (11.9) | 7 (12.5) | 7 (11.3) | |

| Other complications | 13 (11.0) | 6 (10.7) | 7 (11.3) | |

| Treatment in the last 3 weeks, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 31 (26.3) | 6 (10.7) | 25 (40.3) | |

| No | 83 (70.3) | 48 (85.7) | 35 (56.5) | |

| Not coded | 4 (3.4) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (3.2) | |

| OS (months), n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| ≥6 | 71 (60.2) | 42 (75.0) | 29 (46.8) | |

| <6 | 47 (39.2) | 14 (25.0) | 33 (53.2) | |

| Treatment line in the last cycle, n (%) | 0.02 | |||

| First line | 57 (48.3) | 19 (33.9) | 38 (61.3) | |

| Second line | 29 (24.6) | 18 (32.1) | 11 (17.7) | |

| Third line | 15 (12.7) | 11 (19.6) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Fourth line | 5 (4.2) | 3 (5.4) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Fifth line and above | 8 (6.8) | 3 (5.4) | 5 (8.1) | |

| Not coded | 4 (3.4) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Drug in the last cycle, n (%) | 0.005 | |||

| Chemoimmunotherapy | 17 (14.4) | 3 (5.4) | 14 (22.6) | |

| Pembrolizumab | 34 (28.8) | 12 (21.4) | 22 (35.5) | |

| Nivolumab | 5 (4.2) | 2 (3.6) | 3 (4.8) | |

| Platinum | 12 (10.2) | 8 (14.3) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Taxane | 18 (15.3) | 15 (26.8) | 3 (4.8) | |

| Gemcitabine | 17 (14.4) | 9 (16.1) | 8 (12.9) | |

| Vinorelbine | 5 (4.2) | 4 (7.1) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Pemetrexed | 2 (1.7) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Sotorasib | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Not coded | 6 (5.1) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (6.5) |

PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; N/A, not analyzed; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; OS, overall survival.

Statistical analysis of survival

The OS of the population of study was 8 months (95% CI: 6.32–9.67). For patients who had been assessed by the palliative care team, OS was 13 months (95% CI: 7.7–18.2) vs. 6 months (95% CI: 4.6–7.4) for patients who had not been assessed by the team. The rest of the data regarding OS in the sample are included in Table S1.

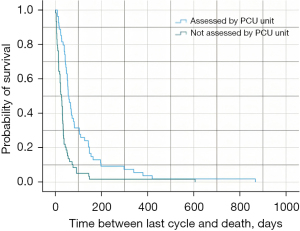

With regard to survival (in days) after the administration of the last cycle of treatment, it was 38 days for the total population of study (95% CI: 30.6–45.4). For patients assessed by the palliative care team, survival after the last cycle of treatment was 56 days (95% CI: 41.6–70.4) vs. 27 days for those who had not been assessed (95% CI: 19.4–34.5) (Plog-rank<0.001) (Table 2, Figure 1). In patients ≥75 years old, survival time was 47 days (95% CI: 33.9–60.1) vs. 34 days (95% CI: 24.9–43.1) in patients <75 years old (Plog-rank<0.001). In patients with high expression (PD-L1 ≥50%), survival was 32 days (95% CI: 21.1–42.8) vs. 43 days (95% CI: 29.0–57.0) for patients with low expression (PD-L1 <50%) (Plog-rank=0.03). The data from the subgroup analysis based on whether or not the patients were assessed by the palliative care unit are included in Table 2. The data on the time between the last treatment cycle and death in the different subgroups included in the study are found in Table S2.

Table 2

| Variables | Distance last cycle and success (days) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Palliative care | No palliative care | Plog-rank | PBreslow | ||

| Study population | 38 (30.6–45.4) | 56 (41.6–70.4) | 27 (19.4–34.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≥75 | 47 (33.9–60.1) | 66 (45.7–86.3) | 32 (26.3–37.7) | 0.07 | 0.01 | |

| <75 | 34 (24.9–43.1) | 56 (48.4–63.6) | 21 (11.5–30.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| PD-L1 expression | ||||||

| ≥50% | 32 (21.1–42.8) | 56 (52.1–59.9) | 15 (6.4–23.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| <50% | 43 (29.0–57.0) | 59 (40.9–77.1) | 31 (25.2–36.8) | 0.03 | <0.001 | |

| Treatment line | ||||||

| First line | 34 (22.8–45.2) | 66 (46.1–85.9) | 28 (21.0–35.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Second line | 41 (32.2–49.8) | 67 (15.0–118.9) | 23 (0.0–46.7) | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Third line or higher | 36 (21.0–51.0) | 52 (34.8–69.2) | 23 (17.1–28.8) | 0.12 | 0.20 | |

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| ECOG 0 | 34 (0.0–74.0) | 69 (N/A) | 34 (0.0–78.0) | 0.18 | 0.22 | |

| ECOG 1 | 34 (28.3–39.7) | 43 (19.9–66.1) | 31 (22.9–39.1) | 0.33 | 0.20 | |

| ECOG 2 | 43 (30.3–55.7) | 56 (42.9–69.1) | 23 (19.5–26.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| ECOG 3 | 36 (26.2–45.8) | 61 (15.6–106.4) | 19 (0.0–54.6) | 0.002 | 0.004 | |

Data are expressed as median (95% CI). PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; N/A, not analyzed; CI, confidence interval.

When the Cox regression model was used to analyze the impact of different predictive values on survival (in days) after the administration of the last cycle of treatment and on the mortality rate, the patients who had not been assessed by the palliative care team presented hazard ratio (HR) =3.23 vs. those who had been assessed by the team (95% CI: 2.01–5.13) (P<0.001) (Figure S1). In patients with high expression (PD-L1 ≥50%) HR was 1.63 vs. patients with low expression (PD-L1 <50%) (95% CI: 1.03–2.54) (P=0.03). In patients with OS <6 months after diagnosis, HR was 1.22 (95% CI: 0.72–2.03) (P=0.50) vs. those with OS ≥6 months. With regard to the treatment, the patients who received immunotherapy ± chemotherapy in their last cycle showed HR =0.86 vs. those who only received chemotherapy (95% CI: 0.52–1.43) (P=0.55). Data regarding the multivariate analysis are shown in Table 3.

Table 3

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessed palliative care (no vs. yes) | 3.23 | 2.01–5.13 | <0.001 |

| PD-L1 expression (≥50% vs. <50%) | 1.63 | 1.03–2.54 | 0.03 |

| OS (<6 vs. ≥6 months) | 1.22 | 0.72–2.03 | 0.50 |

| Treatment (ICI ± ChT vs. ChT) | 0.86 | 0.52–1.43 | 0.55 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; OS, overall survival; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; ChT, chemotherapy.

Active treatment during the last 3 weeks of life

Binary logistic regression was used to analyze the influence of different predictive variables on the administration of active treatment during the last 3 weeks of life of the patients included in the study. For patients who had been assessed by the palliative care unit, the odds ratio (OR) to receive treatment in the last 3 weeks of life was 0.20 (95% CI: 0.07–0.57) (P=0.002). In patients with low expression (PD-L1 <50%) OR was 0.58 (95% CI: 0.23–1.50) (P=0.25). In patients under 75 years old OR was 2.83 (95% CI: 1.03–7.72) (P=0.042). Finally, with regard to sex, the OR in men was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.15–1.34) (P=0.26). Data regarding the multivariate analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 4

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessed palliative care (yes vs. no) | 0.20 | 0.07–0.57 | 0.002 |

| PD-L1 (<50% vs. ≥50%) | 0.58 | 0.23–1.50 | 0.25 |

| Age (<75 vs. ≥75 years) | 2.83 | 1.03–7.72 | 0.042 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.45 | 0.15–1.34 | 0.26 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1.

Subgroups analysis

Analysis of subgroups by age

Age is a highly relevant variable in palliative care studies since interventions can often vary considerably between younger and elderly patients. It is important to note that in patients aged 75 years or older, palliative care can improve quality of life and control symptoms. However, it is more challenging to analyze survival in this subgroup, as it may be influenced by other factors such as frailty and additional comorbidities.

In our study, 48 patients aged 75 years or older were included. Of this group, 25 were evaluated by the palliative care unit, while 23 were not. Survival after the last treatment cycle was 66 days (95% CI: 45.7–86.3) for patients evaluated by the palliative care unit, compared to 32 days (95% CI: 26.3–37.7) for those who were not evaluated (Plog-rank=0.07; PBreslow=0.01). This result suggests a trend toward longer survival in patients evaluated by palliative care, although it did not reach strong statistical significance in the log-rank test. However, the Breslow test did indicate a significant difference, which reinforces the idea that palliative intervention could especially benefit older patients.

On the other hand, 70 patients under 75 years of age were included, of which 31 were evaluated by the palliative care unit, and 39 were not. Survival after the last treatment cycle was 56 days (95% CI: 48.4–63.6) for patients who received a palliative care evaluation, compared to 21 days (95% CI: 11.5–30.5) for those who were not evaluated (Plog-rank<0.001; PBreslow<0.001). In this age subgroup, the survival differences were statistically significant in both tests (log-rank and Breslow), indicating a clear benefit of palliative intervention in improving survival in younger patients.

Analysis of subgroups by PD-L1 expression

PD-L1 expression is the biomarker that currently guides the treatment of patients with mNSCLC, with immunotherapy being the treatment of choice for high expressors (PD-L1 ≥50%). Significant differences in this subgroup may highlight the importance of palliative care in patients who are offered treatments considered less aggressive, as they do not involve chemotherapy but may still have side effects and a negative impact on frail patients.

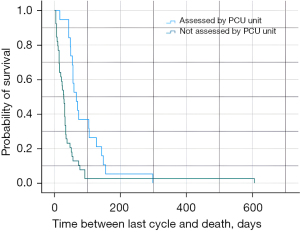

Forty patients presented PD-L1 expression ≥50%, 16 of whom had been assessed by the palliative care unit. In this group, survival after the last cycle was 56 days (95% CI: 52.1–59.9) vs. 15 days (95% CI: 6.4–23.6) for those who had not been assessed (Plog-rank<0.001/PBreslow<0.001) (Figure 1). In 78 patients, PD-L1 expression was <50%; within this group, 40 patients had been assessed by the palliative care unit and their survival after the last cycle was 56 days (95% CI: 40.9–77.1) vs. 31 days (95% CI: 25.2–36.8) for those who had not been assessed (Plog-rank=0.003/PBreslow<0.001) (Figure 2). Data regarding this analysis of subgroups are included in Table 2.

Analysis of subgroups by line of treatment

Showing how the benefit of palliative care is distributed among successive lines of treatment allows oncologists to make better decisions about when it is time to request an evaluation by palliative care teams.

Fifty-seven patients were receiving first line of treatment, 19 of whom had been assessed by the palliative care unit. In this group, survival was 66 days (95% CI: 45.1–85.9) compared to 28 days (95% CI: 21.0–35.0) for patients in the first line of treatment who had not been assessed (Plog-rank<0.001; PBreslow<0.001) (Figure 2).

Twenty-nine patients were in the second line of treatment, 18 of whom had been assessed by the palliative care unit. In this group, survival after the last cycle of treatment was 67 days (95% CI: 15.0–118.9) compared to 23 days (95% CI: 0.0–46.7) for those who had not been assessed (Plog-rank=0.002; PBreslow<0.001).

Finally, 28 patients were in their third line of treatment or higher, and 17 of them had been assessed by the palliative care unit. In this group, survival after the last cycle was 52 days (95% CI: 34.8–69.2) compared to 23 days (95% CI: 17.1–28.8) for those who had not been assessed (Plog-rank=0.12; PBreslow=0.20).

The data regarding this subgroup analysis can be found in Table 2.

Analysis of subgroups by ECOG score

One of the most challenging aspects of palliative medicine is identifying the right time to intervene. Patients with poor ECOG scores (2 or higher) may require more intensive palliative interventions for symptom control, while those with lower ECOG scores may not benefit as much. Evaluating patients’ response to palliative care based on their ECOG score can provide valuable information for validating clinical strategies.

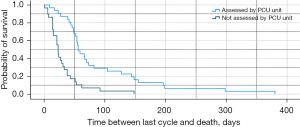

With regard to their functional status, 25 patients had an ECOG score of 1, seven of whom had been assessed by the palliative care unit. In this group, survival after the last cycle was 43 days (95% CI: 19.9–66.1) vs. 31 days (95% CI: 22.9–39.1) in patients who had not been assessed (Plog-rank=0.33/PBreslow=0.20). Out of the 60 patients with ECOG score 2, 31 had been assessed by the palliative care unit, and their survival after the last cycle was 56 days (95% CI: 42.9–69.1) vs. 23 days (95% CI: 19.5–26.5) for those who had not been assessed (Plog-rank<0.001/PBreslow<0.001) (Figure 3). Finally, 28 patients had an ECOG score of 3, 16 of whom had been assessed by the palliative care team. In that group, survival after the last cycle was 61 days (95% CI: 15.6–106.4) vs. 19 days (95% CI: 0.0–54.6) in those who had not been assessed (Plog-rank=0.002/PBreslow=0.004). Data regarding this analysis of subgroups are included in Table 2.

Discussion

This bicentric study tries to analyze the relationship between the assessment by a palliative care unit and a better quality of life during the last stage of life of patients with advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma. We believe that there is a better quality of life in patients who do not receive treatment during the last 21 days of their disease, because this involves a lower number of visits to the day hospital and also a lower number of diagnostic tests [analyses, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, etc.].

Our study analyzes the importance of integrating multidisciplinary teams that include the palliative care unit in the management of patients with advanced NSCLC and its influence on the decision to administer active treatment in the last stages of the disease.

The sample size of patients with an ECOG score of 0 was insufficient to draw significant conclusions in this subgroup during the analysis. This limitation prevents the adequate evaluation of the impact of palliative care on patients who, despite having an optimal functional status, could benefit from its application. It is possible that these patients experience a different progression regarding quality of life, care requirements, and symptom management, which underscores the need for future studies that include a larger number of patients in this category. The sample size of female patients does not allow solid conclusions to be drawn regarding sex differences in the reception and effectiveness of palliative care evaluation. The limited representation of women in the sample, although aligned with the male predominance of patients with NSCLC, may have skewed the results toward a predominantly male perspective, making it difficult to generalize findings to the entire population. Future research should include a larger number of women and aim to evaluate sex differences in the reception and application of palliative care.

One of the strengths of this study lies in the inclusion of patients residing in the province of Salamanca, one of the most sparsely populated areas in Spain and Europe. The inclusion of patients living in both urban and rural areas, where the distance to the reference hospital can exceed 100 km, provides a broad perspective on the impact of palliative care across different sociodemographic and geographic contexts. Thanks to the free and universal Spanish healthcare system, along with the equity policies implemented in the Castilla y León region, equal access to palliative care resources and services was guaranteed for all patients included in this study. This is an important aspect, ensuring that differences in the results are not due to disparities in access to care, but rather to factors inherent to the illness or other characteristics such as demographics, geography, or previous socioeconomic status, which were not analyzed in this study.

However, this characteristic also introduces some limitations that must be considered. First, the studied population has particular epidemiological characteristics, being located in a border area with Portugal and encompassing a geographic zone with specific peculiarities that may not be representative of the broader population of NSCLC patients included in other widely validated international studies, such as those conducted in Canada, Australia, the United States, or Slovenia. Geographic and cultural differences may influence disease patterns, access to healthcare, and responses to palliative treatments, limiting the generalizability of the results to other regions. Secondly, this is a retrospective study, which inherently introduces a potential selection bias by collecting data retrospectively. The analyzed data depend on the quality, complexity, and completeness of the existing clinical records, and relevant information may have been omitted.

The bicentric nature of the study provides a broader perspective compared to single-center studies, although it limits the generalization of results. It has been ensured that there were no differences in treatment protocols and access to resources between the two participating centers; however, differences in daily clinical practice may exist, which could have influenced the statistical analysis.

Finally, although the sample size of this study is relatively small with 118 patients, it is important to note that previous studies in the field of palliative care, both prospective and retrospective, which have included between 100 and 250 patients, have proven to be highly useful and effective in drawing valuable and applicable conclusions in clinical practice. These studies, along with the development of hypotheses, have promoted the advancement of larger, multicentric studies. These studies have significantly contributed to the body of knowledge in palliative care and oncology despite not having massive sample sizes.

In our case, despite the limitation of the sample size, we believe that the rigorous design of the study, the homogeneity in access to healthcare resources, and the inclusion of a diverse population in terms of geographic location (rural and urban) help to strengthen the validity of the findings. The epidemiological context of the patients from a border area in northwestern Spain provides relevant information that can significantly contribute to understanding the impact of palliative care in similar populations. Therefore, we believe that, as in previous studies with comparable sample sizes, the results of this study can be equally useful in contributing to improving daily clinical practice and for future research in the field of palliative care.

The arrival of immunotherapy has revolutionized the treatment of patients with metastatic NSCLC in the last decade (10). This has made it possible for GS to increase from 13 months to over 20 months, and for the long-term survival rate to reach 20–30% (11). Major advances in treatment must not let us forget that, in most cases, stage IV NSCLC is an incurable disease, and that most patients will die as a consequence of complications derived from the progression of the tumor.

In the last years, authors such as Nguyen et al. (12), Beaudet et al. (13), and more recently, Golob et al. (14) have focused on studying the use of oncological active treatment in the last stage of the disease. These studies all report an increased yearly percentage of patients who have been treated in their last stages. Nguyen et al. showed that interventions aimed at improving quality of life can lead to a reduced use of chemotherapy in the last 30 days of life; however, they observed an increase in the use of immunotherapy. In their study, prior to the intervention through multidisciplinary teams that included palliative care specialists, 27% of patients received treatment in the last 30 days of life, similar to our study, where 26.3% of patients received treatment in the last 3 weeks. After the intervention, they reduced the number of patients receiving treatment in the last month to 25%, with a reduction in chemotherapy-related mortality from 8% to 2%. It is worth noting that the authors highlight the importance of the rise of immunotherapy and the difficulties in deciding whether or not to treat patients who may die within the next 30 days. In our study, 30.4% of patients in the palliative care group received chemoimmunotherapy or immunotherapy alone (pembrolizumab or nivolumab) in the last 3 weeks, compared to 62.9% in the group without palliative care. In the palliative care group, 25% of patients received immunotherapy alone in the last 3 weeks, while in the group without palliative care, the percentage was 40.3%. Some authors, such as Glisch et al., have mentioned the growing use of immunotherapy in patients with poor ECOG scores (15). It is likely that these patients were not evaluated by teams that included palliative care physicians. There may currently be a tendency or mistaken perception that immunotherapy is less aggressive than conventional chemotherapy, despite the complexity of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), whose nature is often unpredictable and sometimes severe or fatal (16). It could also be that oncologists face difficulties in withdrawing active treatments, especially when it comes to immunotherapy, even when the benefit may be minimal (17). Glisch et al. (15) emphasize that immunotherapy in the last month of life increases the risk of dying in the hospital. In our study, 74.2% of patients who did not receive palliative care died in the hospital within the Medical Oncology Service. In the group of patients who received palliative care, only 3.6% died while hospitalized.

The study by Beaudet published in 2022 (13) included 90 patients with advanced NSCLC, 22% of whom received treatment within their last 30 days of life. This study emphasizes the negative outcomes for advanced cancer patients who receive chemotherapy at the end of life. The authors observed a shorter OS (4 vs. 9 months), a higher rate of death in the hospital, and fewer opportunities to receive compassionate options such as palliative sedation.

Survival after the administration of the last treatment was 94 days. In our study, we observed that OS was greater than or equal to 6 months in 75% of patients evaluated by palliative care and in 46.8% of patients who were not evaluated by this unit. The study conducted by Golob et al. (14) included 1,736 patients with different types of cancer, 14.4% of whom received treatment during their last 2 weeks of life. The authors highlighted the increase in the use of new therapies (immunotherapy and targeted treatments) in the last stages of the disease highlighting that younger patients and those not evaluated by palliative care units have higher probabilities. Golob et al. also point out that oncologists are likely to perceive that younger patients have a greater ability to tolerate aggressive treatments. This may increase the likelihood of them receiving treatments at stages of the disease where they are not useful. In the audit conducted by Nguyen et al. (12), the authors observed that, out of 440 patients with different subtypes of cancer, 27% of them received treatment during their last 30 days of life.

In our study, the sample size was 118 patients, and 31 of them (26.3%) received active treatment during their last 3 weeks of life. In patients who had received a multidisciplinary assessment that included the palliative care team, 6 (10.7%) received treatment during their last 3 weeks of life vs. 25 (40.3%) who had not been assessed by that team. When the multivariate analysis was performed, the assessment by the palliative care team represented an OR of 0.20 to receive active treatment during the last 3 weeks of life, and these differences were statistically significant. This highlights, in line with other studies shows that an early assessment by multidisciplinary teams that include palliative care specialists reduces the use of aggressive therapies in the last weeks of life, which directly and indirectly leads to an improvement in quality of life (4,12).

Survival after the administration of the last treatment was 38 days. In patients who had been subject to multidisciplinary assessment by the palliative care team, survival after the last cycle was 56 vs. 27 days for those who had not been assessed by the team. These differences were statistically significant, and the multivariate analysis with the Cox regression model showed an HR of 3.23 in patients who had not been assessed by the palliative care team. With regard to sex, we observed that women represented 25.8% of the patients who did not receive palliative care and 10.7% of those who had been assessed by the palliative care team. Although this difference was not statistically significant, it is important to consider that, in general terms, women with mNSCLC are diagnosed at an earlier age than men, and they have fewer toxic habits (tobacco and alcohol consumption) (18). This may involve greater aggressiveness in the oncological treatment, described as the use of immunotherapy by itself or combined with chemotherapy in the last stages of life due to greater expectations of a response to treatment. In our study, we observed that in patients under 75 years old, survival after the last cycle was 56 days in patients assessed by the palliative care team vs. 21 days for those who had not been assessed. The differences were statistically significant and they reinforce the idea that age is a variable that needs to be considering when deciding whether to administer treatment in the advanced stages of the disease.

Out of the patients who did receive palliative care, 38 (67.9%) died in the palliative care unit (hospice) and 15 (26.8%) died at their homes. However, in patients who had not been assessed by this unit, 82.3% of the deaths took place in the hospital environment; 46 (74.2%) in the medical oncology unit and 5 (8.1%) in the intensive medicine unit. The differences were statistically significant. Dying in the medical oncology unit or the intensive medicine unit meant that this subgroup of patients received more therapies in the last stages of their disease, including intravenous antibiotics, corticoids, or active oncological treatment. In addition, this subgroup of patients was also more frequently subject to procedures (venipuncture, urinary catheterization) and imaging tests than patients who died in the palliative care unit (hospice) or at their homes. It is also important to consider that active oncological treatments cause complications, including an increased risk of infections and, since the arrival of immunotherapy, some new ones such as hepatitis, immune-mediated nephritis or even myocarditis (11,19). These complications may sometimes be fatal, and they are often unpredictable. This makes us think that it is impossible not to assume that a certain percentage of patients will die during the administration of active treatment. On the other hand, the appearance of neoplastic syndromes such as tumor-induced hypercalcemia or thrombotic microangiopathy, together with other factors such as the appearance of the disease in the brain, are acute complications that may cause death within a short period of time in patients who were receiving active treatment (20). This is supported by the fact that, among patients who had not been assessed by the palliative care team, 61.3% were receiving first-line treatment, whereas in patients who had been assessed by the team, the percentage of patients receiving first-line treatment was significantly lower (33.9%). It is worth noting that, in patients who had not been assessed by the palliative care team, the last treatment was based on immunotherapy (pembrolizumab) by itself or combined with chemotherapy in 58.1% of the patients. This percentage was only 26.8% for patients who had been assessed by the palliative care team, and the differences were statistically significant.

The functional status, measured with the ECOG scale, is an important biomarker that needs to be considered when assessing the potential survival of patients with NSCLC (21). In our study, no statistically significant differences were observed in patients with ECOG score 1 who had received multidisciplinary assessment that included palliative care. However, the differences were significant in patients with ECOG score 2: survival was 56 days in patients who had been assessed by the palliative care team vs. 23 days for those who had not been assessed. Differences were also significant in patients with ECOG score 3: survival was 61 days in patients who had been assessed by the palliative care team vs. 19 days in those who had not been assessed. This reinforces the key point that palliative care has a measurable impact on survival, particularly in patients with worse functional statuses.

Conclusions

An assessment by multidisciplinary teams that integrate palliative care doctors has a significant impact on the decision to not administer active treatment over the last 3 weeks of life of patients with advanced NSCLC. Patients under 75 years old have a greater risk of receiving active treatment during the last 3 weeks of life even if treatment will not provide significant benefit and will have a negative impact on quality of life.

The greatest benefit of an assessment by palliative care teams is obtained in patients with ECOG scores 2 and 3. We believe that in these groups of patients it would be beneficial to perform, if possible, a multidisciplinary evaluation that includes palliative care teams, which implies an improvement in the quality of life through a lower number of hospital consultations for chemotherapy administration, analytical tests, etc. and a lower number of deaths in hospitalization services. Also, new multicentric studies with large sample size must be carried out to analyze the response to immunotherapy by itself or combined with chemotherapy in patients with a poor functional status. New prognostic biomarkers must be researched to help clinicians in their decision-making process regarding patients with a poor functional status.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and their families for teaching us life lessons every day. We thank David González-Iglesias for his invaluable help in translating this work. L.P.D. thanks Dr. Enrique Sánchez-Casado for his professionalism and the care he shows to patients and families in his work as a palliative care physician. We are also grateful to all the nursing and auxiliary staff of the Oncology and Palliative Care Service in Salamanca, without whom we could never truly speak of patient care.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-97/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-97/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-97/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-24-97/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013), ensuring respect for human rights, the safety, and the well-being of the participants. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Salamanca University Hospital Complex under approval number 2022-10-1155, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Cancer Today. [Cited 9 May 2024]. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/

- Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF. editors. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006.

- Alexander M, Kim SY, Cheng H. Update 2020: Management of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Lung 2020;198:897-907. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woldie I, Elfiki T, Kulkarni S, et al. Chemotherapy during the last 30 days of life and the role of palliative care referral, a single center experience. BMC Palliat Care 2022;21:20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Evaluating claims-based indicators of the intensity of end-of-life cancer care. Int J Qual Health Care 2005;17:505-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kozlov E, Carpenter BD. What is Palliative Care? Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34:241-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deol BB, Binns-Emerick L, Kang M, et al. Palliative care in the older adult with cancer and the role of the geriatrician: a narrative review. Ann Palliat Med 2024;13:819-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simone CB 2nd, Jones JA. Palliative care for patients with locally advanced and metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Palliat Med 2013;2:178-88. [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Jackson VA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Stepped Palliative Care for Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024;332:471-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Socinski MA. Incorporating Immunotherapy Into the Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Practical Guidance for the Clinic. Semin Oncol 2015;42:S19-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leighl NB, Hellmann MD, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-001): 3-year results from an open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:347-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nguyen M, Ng Ying Kin S, Shum E, et al. Anticancer therapy within the last 30 days of life: results of an audit and re-audit cycle from an Australian regional cancer centre. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beaudet MÉ, Lacasse Y, Labbé C. Palliative Systemic Therapy Given near the End of Life for Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Curr Oncol 2022;29:1316-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golob N, Oblak T, Čavka L, et al. Aggressive anticancer treatment in the last 2 weeks of life. ESMO Open 2024;9:102937. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glisch C, Hagiwara Y, Gilbertson-White S, et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Use Near the End of Life Is Associated With Poor Performance Status, Lower Hospice Enrollment, and Dying in the Hospital. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020;37:179-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chhabra N, Kennedy J. A Review of Cancer Immunotherapy Toxicity: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Med Toxicol 2021;17:411-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harris E. Gaps Exist in End-of-Life Immunotherapy Treatment for Cancer. JAMA 2024;331:467. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baiu I, Titan AL, Martin LW, et al. The role of gender in non-small cell lung cancer: a narrative review. J Thorac Dis 2021;13:3816-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rahman MM, Behl T, Islam MR, et al. Emerging Management Approach for the Adverse Events of Immunotherapy of Cancer. Molecules 2022;27:3798. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anwar A, Jafri F, Ashraf S, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in lung cancer and their management. Ann Transl Med 2019;7:359. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyers DE, Pasternak M, Dolter S, et al. Impact of Performance Status on Survival Outcomes and Health Care Utilization in Patients With Advanced NSCLC Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. JTO Clin Res Rep 2023;4:100482. [Crossref] [PubMed]