African American elders’ psychological-social-spiritual cultural experiences across serious illness: an integrative literature review through a palliative care lens

Introduction

As the population of African American (AA) elders increases, there is a need to focus on delivery of culturally congruent care (1). In 2010, there were 38.9 million AA elders, and by the year 2050, AA older adults are projected to account for more than 21.5% of the US population, an increase from 10% in 1990s (2). Yet, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Disparities Report (3), AA elders are less likely than Whites to receive the right amount of support during the time of serious illness. Disparities in seriously ill AA elder care exist because of gaps in knowledge around culturally sensitive physiological, psychological, social, and spiritual palliative care practices (4-7). To facilitate psychological, social, and spiritual healing for the seriously ill AA elder, palliative care practices must be informed by the perspectives of the seriously ill AA elder. Defined for this study, palliative care’s role is “to anticipate, prevent and relieve suffering; to support the best possible quality of life for patients and their families, regardless of the stage of the disease”, not just care provided at end-of-life [(8) p. 9]. Serious illness is defined conceptually as “a persistent or recurring condition that adversely affects one’s daily functioning or will predictably reduce life expectancy” [(8) p. 8].

A review of the current research into psychological, social, and spiritual experiences of seriously ill AA elders can provide insight into creating culturally sensitive approaches for improving quality of life and overall satisfaction with the healthcare received. Research in this area is growing; however, research examining psychological, social, and spiritual healing experiences remains limited in scope, quantity, and location. Through a culturally congruent framework (1), the integration of psychological, social, and spiritual experiences provides holistic, patient-centered care that “identif[ies], respects and address[es] differences in patient values, preferences and expressed needs” [(9) pg.1]. However, a knowledge gap remains in this area, particularly through a culturally focused framework. A view that encompasses the multidimensional concepts of psychological, social, and spiritual healing must evaluate both culture-specific and culture-universal factors to provide culturally congruent care that is beneficial to the people being served (1). Nurses contribute to the healthcare experiences of AA elders through interactive “transpersonal caring moments” [(10) p. 12]. When inadequate care is given, AA elders have experienced insufficient symptom control, difficult interactions with their healthcare providers, lack of spiritual psychosocial support and the possibility of dying without access to high quality care (11-16)

Purpose

The purpose of this culturally focused integrative literature review is to summarize the current research examining AA elders’ psychological, social, and spiritual experiences during serious illness. The following questions guided this review: What cultural experiences contributed to psychological, social, and spiritual healing for AA elders living with serious illness? What cultural experiences contributed to psychological, social, and spiritual suffering for AA elders living with serious illness? The insights obtained from this literature review can contribute to a framework for guiding future empirical research around the cultural phenomenon of psychological, social, and spiritual healing in seriously ill AA elders, thus guiding culturally sensitive approaches to interventions for patient-centered palliative care.

Key definitions

For this review, the following definitions were used to conceptualize the following terms: sociocultural, serious illness, healing, and suffering. Sociocultural was broadly defined: “the interaction between people and the culture in which they live” (17) Serious illness was limited and operationalized in this review to the top four leading causes of death in African Americans: heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes mellitus (18). Healing was defined as generating a “sense of wholeness as a person” [(19) p. 657] despite one’s illness. Healing has also been regarded as a subjective and multidimensional concept (19-30). For this review, healing in the setting of serious illness was defined as a “life transforming, positive, subjective change”—psychological, social, and spiritual healing—that occurs when one experiences a serious illness [(31) p. 1]. Suffering, on the other hand, was defined as a negative psychological, social, and spiritual experience (32).

Methods

Using Whittemore’s (33) method for integrative literature review, an organized and rigorous approach to the literature review process was followed via five steps: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation of findings (33,34). Through this process, existing evidence, from both qualitative and quantitative methodologies was synthesized.

A computer assisted literature search was conducted during July 2013-September 2013. The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, CINAHL, EBSCO, and Web of Science. Many different combinations of search terms were used. Initially, zero articles were found when searching the term “psychological-social-spiritual healing.” Twenty four articles were found using the terms “psychological healing”, “social healing”, and “spiritual healing”. Of the 24 found, 4 met the inclusion criteria and were retained for this review.

Because of the scarcity of the literature, related concepts to psychological, social, and spiritual healing were searched with the assistance of a reference librarian. Broader search terms were used in an attempt to capture the psychological, social, and spiritual healing/suffering phenomenon of seriously ill AA elders. The broader terms searched were: healing, psychological healing, social healing, spiritual healing, spirituality, faith, wisdom, meaning-focused coping, coping, recovery, subjective well-being, thriving, resilience, and optimism. Each of these terms was joined with the term “African American”. Boolean operators were applied to define relationships between keywords like African Americans (and) Blacks. These searches were delimited by the following: samples that included an average age of the sample of their participants age 60 or older; discussed psychological, social and/or spirituality dimensions of AA elders; serious illnesses of cancer, heart disease, stroke or diabetes mellitus; published within the last twenty years; and peer-reviewed primary research reports. Theoretical, commentary and review articles were excluded; however, some of these articles’ reference lists were used as secondary sources of primary studies for comparison to the database searches.

Search results

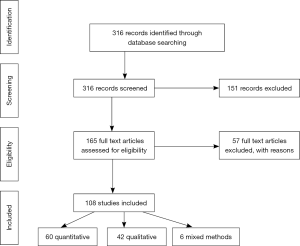

The initial multiple searches, using the above search terms, identified 316 publications. The primary author screened the titles, abstracts, and key words of these 316 publications. Due to duplicates and/or not meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria, 151 articles were removed, leaving 165 publications. The remaining articles were read in their entirety for continued screening with the inclusion/exclusion criteria, leaving 108 articles for this integrative review. The 57 articles removed after this second screening were excluded for several reasons: articles were literature review only; articles only discussed methodological implications of recruitment of AA elders; articles did not include samples with average age of 60 or older, and/or the sample did not include serious illnesses as defined above. From the final 108 publications, the research design, aim/purpose, sample and main findings were extracted into a data matrix. The 108 studies remaining were reviewed for quality and findings (see PRISMA flow diagram, Figure 1).

Results

Evaluation of the literature

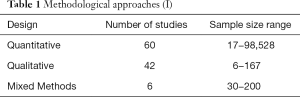

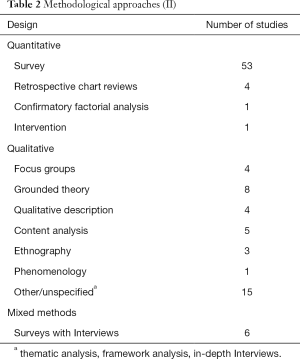

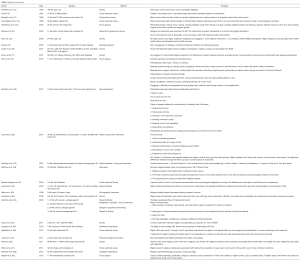

The sample consisted of 60 quantitative, 42 qualitative, and 6 mixed methods studies. The samples of the quantitative studies ranged from n=17 to n=98,528. Of these, 53 were survey research. The remaining 7 of the 60 quantitative studies incorporated several types of methods. Of the 42 qualitative studies, the sample size ranged from n=6 to n=167. Of these, 4 used focus groups and the remaining used interviews for data collection. There were a variety of methodological designs, yet not all of them explicitly stated a design. Of the 6 mixed methods studies, the sample size ranged from n=30 to n=200. These articles used surveys and interviews. The details of the quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies are shown in Tables 1,2.

Full table

Full table

Despite the variety of research methodological approaches, many limitations relevant to the current review were noted. In the quantitative articles, 13 samples were made up of only African Americans, whereas, 47 included multiple ethnicities. For example, in the largest study (n=98,528), a retrospective chart review of Medicare heart failure patients, only 8.5% of the sample was AA (12). Of the quantitative studies, one study sampled African Americans only as part of the “National Survey of American Life” (35,36).

As with the quantitative studies, some of the qualitative studies did not use exclusively AA samples (n=22). However, 20 of the qualitative studies exclusively sampled only AA elders. Joining 3 large narrative analysis studies, the largest qualitative sample, n=167, used only AAs for their sample (37).

Also, there was lack of conceptual clarity around psychological, social, and spiritual concepts. Only 23 of the 108 publications specifically reported a conceptual framework, necessary for providing conceptual clarity. In this survey research, there was no consistency in surveys/instruments or measures employed to measure psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions. For example, the spiritual domain was defined in a variety of ways: spirituality, religiosity, and/or religion practice. Although there was a lack of conceptual clarity of the spiritual domain throughout all the studies, the measurement of the spirituality domain occurred at a much higher frequency than measurements for psychological or social domains. In fact, in the initial literature searches, “spiritual healing and African American,” yielded the largest number of publications (n=29) compared to “social healing and African American” (n=9), and “psychological healing and African American” (n=9).

In the quantitative survey articles, the authors reported difficulty with item non-response, recall bias with self-reported measures and potential selection bias on the part of participants who returned mailed surveys. Large numbers of the survey articles were cross-sectional, and longitudinal studies were frequently recommended by the authors to capture the multi-dimensional psychological, social, and spiritual experiences of serious illness. Most of the 53 survey research studies incorporated only cross-sectional analyses, while only one incorporated a longitudinal approach. Within the survey research, the authors discussed the difficulty of collecting the wide variety of cultural dimensions of AAs elders’ psychological, social, and spiritual aspects due to difficulty using instruments that were not developed within the AA culture. In the survey articles, the authors recommended future research should include qualitative approaches to allow for a more descriptive approach to gain knowledge about culturally focused qualities of the psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions.

A variety of qualitative methodological designs were used; however, not all of them explicitly stated a design/method. However, within the qualitative approaches, specific information such as clinical information, severity of disease, comorbid illnesses or functional status was frequently under-reported. For the mixed methods studies, the authors reported choosing this approach to triangulate the findings of the survey and interviews. All six used surveys and interviews for data collection. Of the largest study (n=200), 200 surveys and 80 ethnographic interviews were conducted. Again, this study’s sample was not made up of only AA individuals, but also included European Americans, Korean Americans and Mexican Americans individuals (38). Finally, many studies only used one geographical location or one healthcare institution, decreasing the ability to collect broader findings across different settings. All studies were completed in the United States except for one in Britain (39).

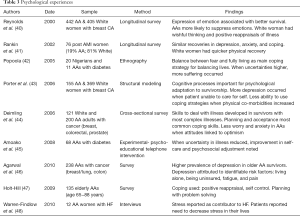

Psychological experiences

As detailed in Table 3, individual psychological experiences found in these studies included depression, fear, anxiety, worry, psychological distress/stress, and sadness. Despite the multitude of negative experiences found, some positive psychological experiences were noted when cognitive reframing of illness occurred. This reframing was described by terms such as optimism, wishful thinking, positive reappraisals, outlook and coping, resilience, and well-adjusted adaptations to one’s illness. The review findings do indicate that positive psychological outcomes do occur for seriously ill AA elders if negative experiences are decreased. When negative experiences decrease, perhaps opportunities emerge for psychological, social, and spiritual healing for the seriously ill AA elder. However, multiple components of seriously ill AA elder’s psychological experiences are still highly understudied, with conflicting evidence of what and how AA elders’ healing/suffering are impacted (see Table 3).

Full table

Social experiences

Social support was shown to impact seriously ill AA’s experiences (see Table 4). Despite research that has shown the benefits of social support, not all AA elders reported a positive role of social support. Negative experiences occurred for some, such as social isolation, decreased intimacy with others; negative social support from family, friends or healthcare providers, concerns about burdening others, and low socioeconomic resources or limited access to care. Social experiences can be impacted either positively or negatively by the healthcare that is provided. AA elders’ social experiences may be negatively impacted by healthcare system discrimination caused by lack of culturally sensitive care, socioeconomic factors, and limited access to care. The findings of this review are consistent with other research on financial, socioeconomic, and access issues in minority populations (3). Studies evaluating the social relationships of seriously ill AA elders with others reveal conflicting evidence. Even in the presence of negative social interactions, some individuals developed strength despite their suffering. The mechanisms contributing to social healing for seriously ill AA elders remains unclear. Therefore, gaining more knowledge from the perspectives of seriously ill AA elders is necessary to determine how these social interactions provide opportunities for healing (see Table 4).

Full table

Spiritual experiences

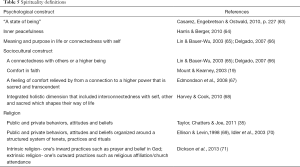

Significant differences were found among definitions of spirituality, religion, and religious practices among publications due to the complex nature of the term spirituality. The incorporation of a broad view of spirituality was important to fully describe healing/suffering for the seriously ill AA elder. For purposes of this integrative review, the source articles defined spiritual healing in the following ways: existential and/or religious practices, psychological and/or sociocultural constructs of spirituality, and with the following terms: spirituality, religion, religiosity or religious practices. Table 5 depicts the most common definitions.

Full table

Spirituality has been shown to play important roles for AA elders dealing with serious illness (see Table 6). When experiences were positive, spirituality provided healing for seriously ill AA elders, whether this occurred through existential, psychologically constructed, or sociocultural religious practices. Based on geographic location, gender or illness, there were noted differences in the roles spirituality played in the lives of seriously ill AA elders. Spirituality was strongly linked to the quality of life of seriously ill AA elders. However, spirituality defined as religious practice did not always show a positive effect on the well being of the AA elder. There remains a lack of conceptual clarity regarding what spirituality is and how spirituality affects suffering/healing for seriously ill AA elders (see Table 6).

Full table

Discussion

Psychological, social, and spiritual healing/suffering

AA elders’ definitions of “health” incorporated mind, body, and spirit (87), and poor subjective health reports predicted lower levels of personal efficacy and spiritual wellbeing (88). Higher spirituality and a sense of control were shown to be significantly associated with decreasing depressive symptoms in AA elders (89). If AA elders experienced stressful life events, this seemed to predict lower subjective health ratings, decreased self-esteem, and lower senses of spiritual wellbeing (88). The use of religious practice to promote mental health among AA elders is well documented (79,84,86,90). Cognitive reframing, religious practice, and the ability to express emotions increased psychological healing and, in some instances, physical function (45).

AA elders were shown to have resiliency and tenacity despite the seriousness of their illnesses (91). Independence gave meaning to life. A strong faith that God was in control guided them through their illnesses (37). Socially, if the AA elder was in a happy marriage, positive effects were also noted on their spiritual wellbeing (88). AA elders’ coping strategies across many illnesses included engaging in life through exercising, seeking information, relying on God, changing dietary patterns, medicating, self-monitoring, and self-advocating (92).

In the studies noted, negative experiences occurred across all three psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions. The negative psychological experiences reported included depression, fear, anxiety, uncertainty, distress, sadness, and fatalism. Negative social experiences stemmed from the following contributors: decreased social support from family, friends or healthcare providers; concerns about burdening others; isolation; low socioeconomic resources; limited access to care; and overt racism and discrimination within their healthcare interactions. When insensitivities to AA elder’s cultural beliefs/values were reported, a concurrent mistrust of the provider was also reported (60). Within the spiritual dimension, negative experiences were not as prevalent. However, a few articles suggested that not all extrinsic religious interactions contributed positive healing effects.

Similarly, positive experiences were reported across all three dimensions. In the psychological dimension, positive experiences included: optimism, resilience, positive coping, and positive outlooks. When cognitive reframing was present, healing could occur. In addition, when individuals had the ability to express their emotions, a social interaction occurred that could also allow for psychological healing. Within the social dimension, quality of life for the seriously ill AA elder is highly linked to positive social support among family and providers, suggesting that positive interactions could lead to less suffering.

For seriously ill AA elders, much overlap occurred in the interactions among culturally relevant psychological, social, and spiritual experiences. Seriously ill AA elders’ psychological and social quality of life were related to their spiritual healing, but a fuller understanding of their cultural values, preferences, and spiritual beliefs is still needed. When discussing healing/suffering, it is important to note that all three dimensions—psychological, social, and spiritual—play important roles for the AA elder’s overall healing.

AA elders’ psychological, social, and spiritual healing within serious illness of cancer

Beliefs based in religiosity were seen in all studies of cancer survivors, but the ways in which religion was expressed in relation to their cancer were culturally determined (39). One study demonstrated that, in cases where breast, prostate, and colorectal AA cancer survivors initially showed poorer physical and mental health quality of life ratings, these ratings changed when adjusted by socio-demographic, clinical, or psychosocial factors, indicating only lower mental health quality of life ratings (93). In another study of cancer survivors, patients reported needing help with overcoming fears, finding hope, finding meaning in life, finding spiritual resources, finding peace, finding meaning to their death and dying, and hoping for someone to talk with about these issues (94). Of these patients, 41% of the AA elders reported needing help with spiritual/existential issues (94). Specifically, in breast cancer, AA women reported positive changes in their faith after diagnosis (95). Finally, in a study of AA lung and colorectal cancer patients, religious behaviors were positively associated with mental health and vitality but had negative associations with depressive symptoms (85).

Breast cancer survivors reported many psychosocial concerns. Other important issues for AA breast cancer survivors included body appearance, social support, health activism, menopause, and learning to live with a chronic illness (96). Breast cancer survivors who had higher coping capacities experienced less psychological distress, higher spiritual wellbeing, and less catastrophizing about their illnesses (97). Coping strategies of breast cancer survivors incorporated all of the following dimensions: relying on prayer; avoiding negative people; developing a positive attitude; having a will to live; and receiving support from family, friends, and support groups (53). Belief in divine control was positively associated across all ethnic groups with not only the positive reframing of illness but also active coping and planning (98).

In AA prostate cancer patients, faith helped patients overcome the fear resulting from initial perceptions of their cancer diagnoses. Faith was placed in God, healthcare providers, self, and family, and these men came to see their prostate cancer as a “new beginning that was achieved through purposeful acceptance or resignation” [(99) p. 470]. This faith was their source of empowerment, and with this empowerment, they became more proactive in their self-care (99). Beliefs based in religiosity were seen in all cancer survivors, but the ways in which religion was understood and expressed in relation to their cancer were culturally determined (39).

In AA cancer survivors, spiritual transformation came through the recognition of personal mortality (80) and through redemption stories that related positive transformations of initially negative perspectives regarding survivorship (100). These transformations occurred through upholding existing beliefs in God, knowing this God as a directing force, and understanding one’s personal strengths (100). The sense of a directing force from God also created a desire to be of service to others (100). Skeath et al. (31) also noted a life transformative experience within a multi-ethnic group of cancer survivors, which impacted all dimensions of their lives. For individuals with serious illness, this positive subjective change impacted the ability to decrease psychological, social, and spiritual suffering, even after a cancer diagnosis (31).

AA’s psychological, social, and spiritual healing within cardiac related serious illnesses: heart failure or stroke

For cardiac illnesses, there was significantly less literature. In contrast to cancer survivors, in AA patients with heart failure, spiritual wellbeing was negatively associated with psychological wellbeing (101). For instance, patients reported feeling less meaning and peace and more depression and anxiety in their lives (101). Yet, these same patients reported greater faith, showing a different relationship to quality of life and faith than that experienced by cancer survivors (101). However, as noted in cancer illnesses, some AA elders were able to maintain a strong sense of self even after the life disruptions caused by heart failure by using the culturally relevant coping strategies of resiliency, spirituality, and self-care (102). In stroke patients, acceptance of illness came as a normal part of aging (103). Patient’s age, other comorbidities, and knowledge about strokes further impacted their overall levels of acceptance (103).

Conclusions

The quantitative literature contained a large proportion of cross-sectional surveys measuring the multidimensional concepts discussed above; however, the studies did not always include a large portion of AA elders. Of most concern is the dearth of literature incorporating all phenomena of psychological, social, and spiritual healing. Despite the lack of conceptual clarity among spirituality and/or religiosity, the spiritual dimensions have been shown to play an important role in healing for seriously ill AA elders, whether this occurred through intrinsic or extrinsic mechanisms. Because of these complex relationships among the psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions, the literature conveys conflicting evidence of what results in suffering for the seriously ill AA elder.

To decrease distrust among AA elders with serious illness, healthcare practice should incorporate physiological, psychological, social, spiritual, and cultural domains to provide patient-centered care of the seriously ill (3,8,104,105). These domains are all part of the National Quality Framework for Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Palliative Care (8).Within this framework, approaches to palliative care interventions in AA elders with serious illness integrate cultural beliefs and values (106-109).

Even with attempts to incorporate psychosocial and cultural concepts into healthcare curricula, inequalities remain (9). “The 21 century brings heightened awareness of how beliefs, values, religion, language and other cultural and socioeconomic factors influence health and help seeking behaviors” [(9) p. 1]. The next generation of healthcare providers, trained through a holistic paradigm (10), will choose to incorporate culture, complexity, and care stemming through relationship-based patient centered care for co-creating a caring and healing environment for AA elders with serious illness (110).

Overall, to facilitate psychological, social, and spiritual healing for the seriously ill AA elder, palliative care practices must be informed by the perspectives of the seriously ill AA elder. When psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions are not incorporated in healthcare delivery, healing can be obstructed and suffering can occur. This integrative review was the first to appraise the state of the science on psychological, social, and spiritual healing in AA elders. The findings identified limitations of the literature and suggested the continued need for healthcare to adopt culturally competent patient centered palliative care. Further research on psychological, social, and spiritual healing is vital to address these limitations and to support culturally focused patient centered palliative care.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my PhD advisor, Anne Rosenfeld, PhD, RN, FAHA, FAAN, Professor and Director of PhD Program at University of Arizona, College of Nursing for her guidance in the construction and editorial review of this integrative literature review and Leslie Dupont, PhD, Instructional Specialist, Sr, Writing Skills Improvement Program, University of Arizona, for her editorial review.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Leininger M. Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research and practices. New York: McGraw-Hill 1995.

- Bulatao R, Anderson N. editors. Understanding Racial and Ethnic Difference in Health in Late Life: A Research Agenda. National Academies Press. [cited 2016 July 5]. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK24684/

- National Health Care Quality and Disparities Report [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. [cited 2016 July 5]. Publica-tion NO.12-0006. Available online: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr11/nhdr11.pdf

- Cohen LL. Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med 2008;11:763-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Evans BC, Ume E. Psychosocial, cultural, and spiritual health disparities in end-of-life and palliative care: where we are and where we need to go. Nurs Outlook 2012;60:370-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnstone MJ, Kanitsaki O. Ethics and advance care planning in a culturally diverse society. J Transcult Nurs 2009;20:405-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1145-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 3rd Edition. [Internet]. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2013. [cited 2016, July 5]. Available online: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org

- Cultural Competency in Baccalaureate Nursing Education. [Internet]. American Association of Colleges of Nursing; 2008. [cited 2016, July 5] Available online: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/leading-initiatives/education-resources/competency.pdf

- Watson J. Intentionality and caring-healing consciousness: a practice of transpersonal nursing. Holist Nurs Pract 2002;16:12-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Enguidanos S, Yip J, Wilber K. Ethnic variation in site of death of older adults dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1411-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Givens JL, Tjia J, Zhou C, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in hospice use among patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:427-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greiner KA, Perera S, Ahluwalia JS. Hospice usage by minorities in the last year of life: results from the National Mortality Followback Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:970-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tanis D, et al. Racial differences in hospice revocation to pursue aggressive care. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwak J, Haley WE, Chiriboga DA. Racial differences in hospice use and in-hospital death among Medicare and Medicaid dual-eligible nursing home residents. Gerontologist 2008;48:32-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connor SR, Tecca M. Measuring hospice care: the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization National Hospice Data Set. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;28:316-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vygotsky L. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1978.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Leading Causes of Death. [Internet]. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013 [cited 2016, July 5]. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lcod.htm

- Mount B, Kearney M. Healing and palliative care: charting our way forward. Palliat Med 2003;17:657-8. [PubMed]

- Denz-Penhey H, Murdoch C. Personal resiliency: serious diagnosis and prognosis with unexpected quality outcomes. Qual Health Res 2008;18:391-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dossey B. Holistic Nursing. In J. Levin, J. (Eds.), Essentials of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 1999:322-39.

- Egnew TR. The meaning of healing: transcending suffering. Ann Fam Med 2005;3:255-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feudtner C. Hope and the prospects of healing at the end of life. J Altern Complement Med 2005;11 Suppl 1:S23-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fleury J, Kimbrell LC, Kruszewski MA. Life after a cardiac event: women's experience in healing. Heart Lung 1995;24:474-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koithan M, Verhoef M, Bell IR, et al. The process of whole person healing: "unstuckness" and beyond. J Altern Complement Med 2007;13:659-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuhn CC. A spiritual inventory of the medically ill patient. Psychiatr Med 1988;6:87-100. [PubMed]

- Jonas WB, Chez RA. Recommendations regarding definitions and standards in healing research. J Altern Complement Med 2004;10:171-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Landmark BT, Wahl A. Living with newly diagnosed breast cancer: a qualitative study of 10 women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. J Adv Nurs 2002;40:112-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saunders C. A personal therapeutic journey. BMJ 1996;313:1599-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swatton S, O’Callaghan J. The experience of ‘healing stories’ in the life narrative: a grounded theory. Couns Psychol Q 1999;12:413-29. [Crossref]

- Skeath P, Norris S, Katheria V, et al. The nature of life-transforming changes among cancer survivors. Qual Health Res 2013;23:1155-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrell BR, Coyle N. The nature of suffering and the goals of nursing. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008;35:241-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whittemore R. Combining evidence in nursing research: methods and implications. Nurs Res 2005;54:56-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005;52:546-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe S. Non-organizational religious participation, subjective religiosity, and spirituality among older African Americans and Black Caribbeans. J Relig Health 2011;50:623-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jackson JS. Religious and spiritual involvement among older african americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: findings from the national survey of american life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007;62:S238-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Becker G, Gates RJ, Newsom E. Self-care among chronically ill African Americans: culture, health disparities, and health insurance status. Am J Public Health 2004;94:2066-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, et al. Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:1779-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, et al. "I know he controls cancer": the meanings of religion among Black Caribbean and White British patients with advanced cancer. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:780-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reynolds P, Hurley S, Torres M, et al. Use of coping strategies and breast cancer survival: results from the Black/White Cancer Survival Study. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:940-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rankin SH. Women recovering from acute myocardial infarction: psychosocial and physical functioning outcomes for 12 months after acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung 2002;31:399-410. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Popoola MM. Living with diabetes: The holistic experiences of Nigerians and African Americans. Holist Nurs Pract 2005;19:10-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Porter LS, Clayton MF, Belyea M, et al. Predicting negative mood state and personal growth in African American and White long-term breast cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med 2006;31:195-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deimling GT, Wagner LJ, Bowman KF, et al. Coping among older-adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2006;15:143-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amoako E, Skelly AH, Rossen EK. Outcomes of an intervention to reduce uncertainty among African American women with diabetes. West J Nurs Res 2008;30:928-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal M, Hamilton JB, Crandell JL, et al. Coping strategies of African American head and neck cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol 2010;28:526-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holt-Hill SA. Stress and coping among elderly African-Americans. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc 2009;20:1-12. [PubMed]

- Warren-Findlow J, Issel LM. Stress and coping in African American Women with chronic heart disease: a cultural cognitive coping model. J Transcult Nurs 2010;21:45-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guidry JJ, Aday LA, Zhang D, et al. The role of informal and formal social support networks for patients with cancer. Cancer Pract 1997;5:241-6. [PubMed]

- Bourjolly JN. Differences in religiousness among black and white women with breast cancer. Soc Work Health Care 1998;28:21-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bourjolly JN, Kerson TS, Nuamah IF. A comparison of social functioning among black and white women with breast cancer. Soc Work Health Care 1999;28:1-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bowie J, Sydnor KD, Granot M. Spirituality and care of prostate cancer patients: a pilot study. J Natl Med Assoc 2003;95:951-4. [PubMed]

- Henderson PD, Gore SV, Davis BL, et al. African American women coping with breast cancer: a qualitative analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2003;30:641-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shellman J. "Nobody ever asked me before": understanding life experiences of African American elders. J Transcult Nurs 2004;15:308-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones RA, Taylor AG, Bourguignon C, et al. Family interactions among African American prostate cancer survivors. Fam Community Health 2008;31:213-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Black HK, Rubinstein RL. The effect of suffering on generativity: accounts of elderly African American men. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64:296-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones RA, Wenzel J, Hinton I, et al. Exploring cancer support needs for older African-American men with prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1411-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tkatch R, Artinian NT, Abrams J, et al. Social network and health outcomes among African American cardiac rehabilitation patients. Heart Lung 2011;40:193-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hinojosa R, Haun J, Hinojosa MS, et al. Social isolation poststroke: relationship between race/ethnicity, depression, and functional independence. Top Stroke Rehabil 2011;18:79-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chatman MC, Green RD. Addressing the unique psychosocial barriers to breast cancer treatment experienced by African-American women through integrative navigation. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc 2011;22:20-8. [PubMed]

- DiIorio C, Steenland K, Goodman M, et al. Differences in treatment-based beliefs and coping between African American and white men with prostate cancer. J Community Health 2011;36:505-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harper FW, Nevedal A, Eggly S, et al. "It's up to you and God": understanding health behavior change in older African American survivors of colorectal cancer. Transl Behav Med 2013;3:94-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casarez RL, Engebretson JC, Ostwald SK. Spiritual practices in self-management of diabetes in African Americans. Holist Nurs Pract 2010;24:227-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harris BA, Berger AM, Mitchell SA, et al. Spiritual well-being in long-term survivors with chronic graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Support Oncol 2010;8:119-25. [PubMed]

- Lin HR, Bauer-Wu SM. Psycho-spiritual well-being in patients with advanced cancer: an integrative review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 2003;44:69-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Delgado C. Sense of coherence, spirituality, stress and quality of life in chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;39:229-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edmondson D, Park CL, Blank TO, et al. Deconstructing spiritual well-being: existential well-being and HRQOL in cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2008;17:161-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harvey IS, Cook L. Exploring the role of spirituality in self-management practices among older African-American and non-Hispanic White women with chronic conditions. Chronic Illn 2010;6:111-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Educ Behav 1998;25:700-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Measuring multiple Dimension of religion and spirituality for health research: Conceptual background and Findings from the 1998 general social survey. Res Aging 2003;25:327-65. [Crossref]

- Dickson VV, McCarthy MM, Howe A, et al. Sociocultural influences on heart failure self-care among an ethnic minority black population. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2013;28:111-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chatters LM, Levin JS, Taylor RJ. Antecedents and dimensions of religious involvement among older black adults. J Gerontol 1992;47:S269-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powe BD. Cancer fatalism-Spiritual perspectives. J Relig Health 1997;36:135-44. [Crossref]

- Cunningham WE, Burton TM, Hawes-Dawson J, et al. Use of relevancy ratings by target respondents to develop health-related quality of life measures: an example with African-American elderly. Qual Life Res 1999;8:749-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ark PD, Hull PC, Husaini BA, et al. Religiosity, religious coping styles, and health service use: racial differences among elderly women. J Gerontol Nurs 2006;32:20-9. [PubMed]

- Harvey IS. Self-management of a chronic illness: An exploratory study on the role of spirituality among older African American women. J Women Aging 2006;18:75-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arcury TA, Stafford JM, Bell RA, et al. The association of health and functional status with private and public religious practice among rural, ethnically diverse, older adults with diabetes. J Rural Health 2007;23:246-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dunn KS, Riley-Doucet CK. Self-care activities captured through discussion among community-dwelling older adults. J Holist Nurs 2007;25:160-9; discussion 170-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamilton JB, Powe BD, Pollard AB 3rd, et al. Spirituality among African American cancer survivors: having a personal relationship with God. Cancer Nurs 2007;30:309-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levine EG, Yoo G, Aviv C, et al. Ethnicity and spirituality in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2007;1:212-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Samuel-Hodge CD, Watkins DC, Rowell KL, et al. Coping styles, well-being, and self-care behaviors among African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2008;34:501-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levine EG, Aviv C, Yoo G, et al. The benefits of prayer on mood and well-being of breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:295-306. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, et al. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2009;18:753-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamilton JB, Stewart BJ, Crandell JL, et al. Development of the Ways Of Helping Questionnaire: a measure of preferred coping strategies for older African American cancer survivors. Res Nurs Health 2009;32:243-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holt CL, Oster RA, Clay KS, et al. Religiosity and physical and emotional functioning among African American and White colorectal and lung cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol 2011;29:372-93. [PubMed]

- Hamilton JB, Sandelowski M, Moore AD, et al. "You need a song to bring you through": the use of religious songs to manage stressful life events. Gerontologist 2013;53:26-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armer JM, Conn VS. Exploration of spirituality & health among diverse rural elderly individuals. J Gerontol Nurs 2001;27:28-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tran TV, Wright R Jr, Chatters L. Health, stress, psychological resources, and subjective well-being among older blacks. Psychol Aging 1991;6:100-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Archibald PC, Dobson Sydnor K, Daniels K, et al. Explaining African-Americans' depressive symptoms: a stress-distress and coping perspective. J Health Psychol 2013;18:321-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamilton JB, Moore AD, Johnson KA, et al. Reading the Bible for guidance, comfort, and strength during stressful life events. Nurs Res 2013;62:178-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Becker G, Newsom E., et al. Resilience in the face of serious illness among chronically ill African Americans in later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2005;60:S214-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loeb SJ. African American older adults coping with chronic health conditions. J Transcult Nurs 2006;17:139-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matthews AK, Tejeda S, Johnson TP, et al. Correlates of quality of life among African American and white cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 2012;35:355-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moadel A, Morgan C, Fatone A, et al. Seeking meaning and hope: self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically-diverse cancer patient population. Psychooncology 1999;8:378-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fatone AM, Moadel AB, Foley FW, et al. Urban voices: the quality-of-life experience among women of color with breast cancer. Palliat Support Care 2007;5:115-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilmoth MC, Sanders LD. Accept me for myself: African American women's issues after breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001;28:875-9. [PubMed]

- Gaston-Johansson F, Haisfield-Wolfe ME, Reddick B, et al. The relationships among coping strategies, religious coping, and spirituality in African American women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 2013;40:120-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Umezawa Y, Lu Q, You J, et al. Belief in divine control, coping, and race/ethnicity among older women with breast cancer. Ann Behav Med 2012;44:21-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maliski SL, Connor SE, Williams L, et al. Faith among low-income, African American/black men treated for prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs 2010;33:470-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gallia KS, Pines EW. Narrative Identity and Spirituality of African American Churchwomen Surviving Breast Cancer Survivors. J Cultur Divers 2009;16:50-5.

- Bean MK, Gibson D, Flattery M, et al. Psychosocial factors, quality of life, and psychological distress: ethnic differences in patients with heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs 2009;24:131-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hopp FP, Thornton N, Martin L, et al. Life disruption, life continuation: contrasting themes in the lives of African-American elders with advanced heart failure. Soc Work Health Care 2012;51:149-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faircloth CA, Boylstein C, Rittman M, et al. Sudden illness and biographical flow in narratives of stroke recovery. Sociol Health Illn 2004;26:242-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. National Quality Forum. [cited 2016, July 5]. Available online: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/04/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care—A_Consensus_Report.aspx

- A Comprehensive Framework and Preferred Practices for Measuring and Reporting Cultural Competency: A Consensus Report. [Internet]. Na-tional Quality Forum. [cited 2016, July 5]. Avaliable online: http://www.calendow.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/By_Topic/Culturally_Competent_Health_Systems/General/NQF%20Cultural%20Competency%20Report.pdf

- Andrews M, Boyle J. Transcultural concepts in nursing care, 5thed. Philadelphia PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Leininger M, McFarland M. Transcultural Nursing: Concepts, theories, research and practice, 3rd Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002.

- Purnell L, Paulanka B. Transcultural health care: A culturally competent approach, 3rd ed., Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 2008.

- Singer PA, Bowman KW. Quality end-of-life care: A global perspective. BMC Palliat Care 2002;1:4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boykin A, Schoenhofer S, Valentine K. Health care system transformation for nursing and healthcare leaders: Implementing a culture of caring. New York: Springer Publishing 2013.