Perceptions and types of support coming from families caring for patients suffering from advanced illness in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo

Introduction

Palliative care is support provided to patients whose disease does not respond to treatment anymore (1); such a pathological stage is also called “advanced illness” (2).

Care can be provided in healthcare facilities, at home or in reference centers, relatively simply and inexpensively (1). It is an approach based on holism, singularity and proportionality of care. Palliative care represents an undoubted support for patients and family members, but to date, only one person out of ten in need benefits from it, at the world level (3). The low level of awareness on these therapeutics and their advantages among the general public seem to be major barriers. To this can be added cultural and social barriers such as beliefs on death and how to die (1). Investigations carried out in Africa among patients suffering from advanced illness highlight the lack of palliative care as well as the significant increase of non-transmissible chronic diseases. In addition, mismatches between request and accessibility to care have been reported (4,5). As a result, families and community agents are among the main actors (1) for palliative care, providing support to patients with advanced illness.

In low-income countries, families care for the hygiene and nutrition of patients in almost all hospitals. Their participation in the implementation of palliative care significantly reduces the patient’s psychological distress (6). Their support is seen as a social duty, but also contributes to the morale and hope for remission.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the incidence of poverty is very high (71.34%) compared to other countries of Central Africa (7). About 70% of patients have no access to modern healthcare due to the lack of financial resources; the poor quality of services is also influenced by the lack of national resources (7). Healthcare expenses of Congolese families are mainly achieved through direct payments to healthcare providers, which means covering as much as 94% in 2010 to 97% in 2011 of the bill (8). In addition to cultural reasons and geographical accessibility, these high costs are an incentive for preferring traditional medicine rather than consulting the modern health system in approximately two families out of ten (9). Consequently, the majority of patients arrive at healthcare facilities in advanced stages of disease (10-12). The present study aimed at documenting the perceptions of families on the care of patients suffering from advanced illness and identifying support provided by healthcare facilities, in a Congolese context.

Methods

A qualitative study based on focus groups was carried out among families of patients suffering from advanced illness and hospitalized between August and September 2015, in six Kinshasa hospitals; the characteristics of these hospitals are described in Table 1. They were selected because of their urban environment, offering perceptions of people from different social classes.

Full table

According to our experience and observations, confessional (or “religious”) hospitals are well structured and equipped, and provide care with a certain degree of compassion.

Their supply in medications is better compared to public and private hospitals. In addition, private hospitals are more expensive compared to public and confessional institutions in terms of care and hospitalization expenditures.

A patient’s family is represented by the person at his/her bedside. The nurse responsible for each hospital ward where surveys were performed pre-selected eligible participants. The eligibility criteria were the following: age ≥18 years old, physical and mental capacity to participate in a focus group and consent to participate in the survey. Participation was on a voluntary basis. Investigators were professors and trainers of the Kinshasa Higher Institute of Medical Engineering “ISTM/Kinshasa”. Before starting focus groups, a clear explanation on the aim of the study was provided to all participants. Authorizations were obtained through verbal informed consent of each participant, with guarantee of anonymity and non-dissemination of recordings. Initially, almost all participants refused that the discussions be recorded, the voice recorder being regarded as journalistic equipment. Following a clear explanation, supported by hospital caregivers, an agreement allowing for recordings was reached.

To help lead the discussion, an interview guide, with various questions outlining specific themes, was provided. With this guide, the participants shared information on the clinical signs and diseases affecting hospitalized patients, communication between care provider and patient, transport of patients to hospitals, painkillers consumed, as well as the care and support provided to the families during hospitalization. After translation in Lingala, the interview guide was validated by two family members who were not included in the study.

In each hospital, each participant was free to express him/herself, either in French, or in vernacular (Lingala) language. Such options prevented discrimination towards anybody and actively included each person in the discussion. Sociodemographic data collected for participants included the following: sex, marital status, education level, family relationship to the patient, duration of illness, residency area and religion. Each focus group included eight participants (males and females). Discussions lasted about 90 min and were recorded, then integrally transcribed. Coordination was ensured by the main investigator, who was in charge of clarifying questions when necessary and keeping the dialogue directed at the objective of the study. Apart from the main investigator, four health professionals, two doctors and two licensed nurses with experience in investigation and, previously trained in qualitative methods, participated in data collection; these professionals, along with the nurse responsible for each hospital ward, observed and enrolled participants, took note of participants’ reactions and ensured that the discussion was recorded. They also helped transcribe recorded discussions. Upon ending each focus group, a debriefing between the main moderator and other members of the investigation team was held. Analysis of the content was performed on the transcriptions and on notes taken during focus groups. A thematic analysis of the verbatim conversation was carried out according to the hospital in which the discussion was recorded and according to the characteristics of participants (residency area and sex).

The present protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (approbation number: ESP/CE/084/13), as well as by the committee of administrative authorities in selected hospitals.

Results

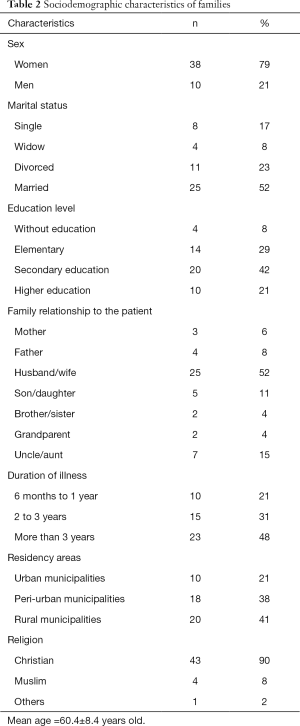

The main sociodemographic characteristics of studied families are summarized in Table 2.

Full table

More than three-quarters of participants (79%) were women, aged about 60 years old; 52% were married, 42% had reached the secondary education level and 48% reported that the illness of the relative lasted for more than 3 years. About one participant out of two lived in a rural municipality. Most participants (90%) were Christians.

During interviews, participants expressed their perceptions on the main themes related to the care of patients.

Clinical signs and diseases affecting hospitalized patients

In general, participants declared that hospitalized relatives (patients) showed clinical signs of illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, cancer, long-lasting wounds, aches in lower limbs, backache, diarrhea, fatigue, anemia and heart complications (e.g., “My mother has been suffering from complications of high blood pressure and diabetes for a long time”, or “My mother has reached an advanced stage of cancer”). Most patients had been suffering for more than 10 years and had reached an advanced stage of illness (e.g., “My father has been suffering from a heart condition for more than 10 years”).

However, some participants were unaware of what their hospitalized relative was suffering from, but reported several hospitals stay (e.g., “So far, we do not know about our mother’s illness”).

Communication between care provider and patient

Participants mentioned a lack of communication between care providers and patients, especially regarding doctors (e.g., “I ask the doctor if my mother is fine, but he answers to me that a lot of money is necessary”). Participants mentioned a regular lack of contact with doctors and nurses (e.g., “We do not see the doctor after the clinical round”). Some doctors prefer communicating in French with families, even though they can speak Lingala (e.g., “The doctor knows Lingala, but he often prefers speaking French with us”).

Transport of patients to the hospital

Participants described that many paths and roads leading to the hospital were destroyed. Some families must travel more than 1,000 km (east of the country) to seek care in Kinshasa (e.g., “We come from the eastern part of the country, which means more than 2,000 km of distance, so far, only complementary clinical examinations have been performed”). Means of transportation differ according to the family’s social environment and financial resources. Some of them travel long distances on foot (sometimes carrying the patient on one’s back), by bike or by canoe to reach healthcare facilities (e.g., “We transported our father on our back, then we found a bike to reach the district hospital, then after a vehicle to go to Kinshasa”).

Cost of painkillers and other health expenditures

Among all residency areas (urban, peri-urban and rural), participants reported that painkillers were scarce and expensive (e.g., “Painkillers are scarce and expensive, we need a miracle!”; “We have had the prescription for two weeks, but…”). They say they have sold everything, they do not have any savings (economic resiliency) because everything needs to be paid (e.g., “We do not have savings, we have to pay for everything, such as syringes and gloves”). Some participants were expecting money from abroad (Europe, America, Angola and South Africa) to buy medicine and other supplies (e.g., “Since yesterday, we have been waiting for money from Belgium to buy painkillers and pay the bills”). Participants also mentioned the exorbitantly expensive expenditures in reference centers (e.g., “My father must undergo a heart surgery, but it must be done in Belgium and we have to find 25,000 euros for the surgery, but what can we do?”).

Care of patients

Participants described the care as being largely inaccessible and of poor quality. Circumstances and requirements to benefit from care were a source of anxiety and fear. They specified that payment was required before being allowed access to nursing care and other forms of care (e.g., “Healthcare is of a poor quality; there are buildings, but no care!”; “Some patients are located at the end of the hallway: what does this mean? Isolation, negligence?”). The use of bribes for rapid and correct care was also admitted (e.g., “I pay bribes so that people take good care of my mother”). Moreover, according to all participants, psychological support is lacking even though it is a particularly important aspect in the care of advanced illness (e.g., “We totally lack psychological support; we are the poor, the weak!”; “We also suffer from seeing him suffer!”). Participants were not satisfied with the care provided by hospital staff; they even suggested that some staff members should go back to school to better learn how to take care of patients. The behavior of caregivers does not inspire confidence. Families come for healing (e.g., “For me, some caregivers should go back to school”).

Reactions to the prognosis of the advanced stage of illness varied (e.g., “We are ready for just about anything if it is necessary to go back home”; “With my uncle’s disease, we just have to pray”).

Some participants mentioned being able to take loans or pay in several installments when consulting traditional practitioners. The desire for an alternative solution was also raised by participants (e.g., “When at the traditional practitioner’s, he first gave us the product, and the money was considered after; but here, money before care!”; “The traditional practitioner does not set the price to pay, we can pay little by little”; “The most important thing is to cure the patient someday”).

Financial support provided to families during hospitalization

Participants mentioned support and other resources helping them face health expenditures of the hospitalized relative. They received external financial support coming from Europe, America, Angola and South Africa, as well as from the religious cult. Through African solidarity, some participants benefited from support for the care of the hospitalized relative from family members abroad (e.g., “We have support through family members who are in Europe”; “Our support, ah! They only come from our religious brothers!”).

Discussion

In DRC, few studies have tried to document through a qualitative approach family perceptions and potential support provided by healthcare facilities to patients suffering from advanced illness. Such care is of great importance in the context of the epidemiological transition of chronic diseases in a low-income country (13,14). A more recent study from Kenya identified palliative care and hospice services as important components in the management of chronic illness (15). Notes and observations collected in focus groups allowed investigators to elucidate different elements that were divided into three groups.

Perceptions by families on organizational problems in the care of patients

A preoccupation reflected by participants in the study was the lack of communication between caregivers and patients, which mainly involves doctors who do not clearly communicate information on the stage of the disease. Such results corroborate the observations of Glogowska (16) regarding the conversation on advanced illness of patients. In palliative care, communication is an efficient therapeutic resource (17-19). It must account for differences in perceptions (1,20). It is essential that adequate means (dialogue between partners, meetings gathering caregivers and family) and the right moment (after the clinical round, the care or the meals) are identified (21,22). Several families do not accept the fact that death is a part of every human’s reality. Indeed, ideas and thoughts of death are interpreted differently across various cultures, and the absence of knowledge of the disease trajectory and what to expect down the road with their physician (23).

When talking with illiterate families, some doctors prefer speaking French, which negatively influences the care of the patient and confirms the observations of Yeo (24). Language barriers are associated with a poor comprehension of the doctor’s message (24). We need not only more communication, but especially novel sensitive cultural means of the communication (25).

As observed in several African countries (26), lack of psychological support was underlined by many participants. This is strongly correlated with the quality of life (27). Regardless of the residency area, participants mentioned the scarcity and expensive cost of painkillers, which confirms information compiled in the narrative report on DRC pharmaceutical profile (28). In Africa, families have poor financial resources, which are not sufficient to support health expenditures associated with the care of a patient suffering from an advanced illness, generating late admission to the hospital (29). Patients feel guilty for having used all of the family’s resources (30).

Family situations and potential support provided by healthcare facilities

Economic resiliency appears to have motivated belief in religious healing among participants, which corroborates previous African studies (31). Instability seems to create obstacles to the implementation of palliative care (21).

As reported in Tanzania, access to hospitals is difficult for families as means of transportation are scarce and the road network is of a poor quality (32).

It is well known that, in numerous low-income countries, families search for alternative solutions to fight and reduce the pain of a patient undergoing a chronic treatment. Other studies have shown similar results in cases of advanced illness, for which the decision-making process is dynamic and complex (33). This may include quality of life and other subjective aspects (34,35).

Any suffering end-of-life patient wishes to die peacefully and to be taken care of at home, without feeling dependent upon others; she/he will then privilege home-based care (36). Nevertheless, strong religious beliefs relieve the pain and give hope for the future (37).

Our study also highlighted that relatives taking care of a patient were receiving support from the wider family and from members of the religious community. These observations are linked to the socioeconomic context of DRC. As shown in previous demographic surveys performed in DRC (38) and in Powell’s study (39), virtually all participants displayed a religious affiliation, which is linked to an inherent feeling of mutual assistance. In addition, the report on national health counts showed that the DRC budget allocated to health was very low in 2011 (4.45%) (8). Households remained the main financial source of the DRC health system (i.e., 40% in 2010) (8).

Illnesses affecting patients and characteristics of families

Symptoms and signs of complications related to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) were the most commonly referred to in the present study. Such results confirm the observations of previous studies carried out in Sub-Saharan Africa (4,40-42). The epidemiological transition may partly explain such trend. Most participants were women (79%), which is in accordance with African tradition. Within African families, women rarely have jobs. They are often stay-at-home mothers while men work to meet daily financial and material needs of household. In our context, about one participant out of two was married at the time of the study. Such findings are similar to the observations of the second DRC demographic and health survey (EDS-RDC II 2013-2014), where almost one of two women and men were married (38). This observation reflects the cultural importance of marriage in this country.

Almost 50% of participants lived in a rural municipality, in line with previous data reported in Kinshasa and highlighting that rural municipalities were more populated (43). Rural exodus due to armed conflicts and the consequent lack of work in affected provinces could justify such a situation.

Limitations of the study

The main limitation of the study is that it only focused on families whose relative was hospitalized, which prevents the possibility of extrapolation to all families whether at home or in the hospital setting.

Conclusions

In the present study, through personal interviews, families revealed elements that may negatively influence the care of a patient suffering from an advanced illness. These elements include, among others: scarcity of and inaccessibility to painkillers, economic resiliency, poor quality of care, lack of psychological support, the quest for an alternative solution and poor communication between caregivers and patients. In addition, the study highlighted that relatives who take care of a patient often received financial support from the wider family and from members of the religious community. These observations, particular to Kinshasa families, must be considered in the sociocultural Congolese context for the policies of care to persons suffering from advanced illness. The inclusion of families who care for a patient in the home setting and in other social contexts would contribute significantly to the widening of results.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants to focus groups in the six Kinshasa hospitals selected, for their cooperation and open-mindedness, as well as the persons responsible for these hospitals for allowing the survey. Our thanks also go to Dr. Christiane Duchesnes, Department of General Medicine, University of Liège, for her suggestions, optimal analysis of data writing of the manuscript.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. Soins Palliatifs. 2015. [In French]. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/fr/

- World Health Organization. Cancer. 2015. [In French]. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/fr/

- World Health Organization. First ever global atlas identifies unmet need for palliative care. 2015. [In French]. Available online: www.who.int/entity/mediacentre/news/releases/2014/palliative-care-20140128/fr/

- Busolo DS, Woodgate RL. Using a supportive care framework to understand and improve palliative care among cancer patients in Africa. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:284-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacinto A, Masembe V, Tumwesigye NM, et al. The prevalence of life-limiting illness at a Ugandan National Referral Hospital: a 1-day census of all admitted patients. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:196-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weißflog G, Mehnert A. Family Focused Grief Therapy - A Suitable Model for the Palliative Care of Cancer Patients and their Families? Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2015;65:434-8. [PubMed]

- Ministère de la santé publique RDC. Plan national de développement sanitaire PNDS 2011-2015 [in French]. 2010. Available online: http://www.congoforum.be/upldocs/PNDS%202011-2015-KNT.pdf

- Ministère de la santé publique RDC. Comptes Nationaux de la Santé 2010 et 2011 RDC [in French]. 2011. Available online: http://www.minisanterdc.cd/new/images/Documents/CCM/CNS_RD_Congo_Rapport_final_2010_2011.pdf

- Manzambi JK, Tellier V, Bertrand F, et al. Les déterminants du comportement de recours au centre de santé en milieu urbain africain: résultats d’une enquête de ménage menée à Kinshasa, Congo. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2000;5:563-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kautako-Kiambi M, Aloni-Ntetani M, Pululu P, et al. Socio-demographic, biological and clinical profile of patients living with HIV during screening in a voluntary counselling and screening centre in a rural area of Mbanza-Ngungu, Democratic Republic of Congo, in 2006-2011. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 2013;106:180-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pakasa NM, Sumaili EK. The nephrotic syndrome in the Democratic Republic of Congo. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1085-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krzesinski JM, Sumaili KE, Cohen E. How to tackle the avalanche of chronic kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa: the situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo as an example. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22:332-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boutayeb A. The double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases in developing countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2006;100:191-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boutayeb A, Boutayeb S. The burden of non communicable diseases in developing countries. Int J Equity Health 2005;4:2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zubairi H, Tulshian P, Villegas S, et al. Assessment of palliative care services in western Kenya. Ann Palliat Med 2017;6:153-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glogowska M, Simmonds R, McLachlan S, et al. "Sometimes we can't fix things": a qualitative study of health care professionals' perceptions of end of life care for patients with heart failure. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trovo de Araujo MM, Paes da Silva MJ. Communication with dying patients--perception of intensive care units nurses in Brazil. J Clin Nurs 2004;13:143-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore CD. Communication issues and advance care planning. Semin Oncol Nurs 2005;21:11-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trovo de Araújo MM, da Silva MJ. Communication strategies used by health care professionals in providing palliative care to patients. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2012;46:626-32. [PubMed]

- Hinchey J, Goldberg J, Linsky S, et al. Knowledge of Cancer Stage among Women with Nonmetastatic Breast Cancer. J Palliat Med 2016;19:314-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Gurp J, Soyannwo O, Odebunmi K, et al. Telemedicine's Potential to Support Good Dying in Nigeria: A Qualitative Study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126820. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tulsky JA. Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. J Palliat Med 2005;8 Suppl 1:S95-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Senderovich H, Wignarajah S. Overcoming the challenges associated with symptom management in palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2017;6:187-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeo S. Language barriers and access to care. Annu Rev Nurs Res 2004;22:59-73. [PubMed]

- Lorenz KA. Quality of end-of-life care: how far have we come in addressing the needs of multicultural patients? Ann Palliat Med 2017;6:3-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harding R, Selman L, Agupio G, et al. The prevalence and burden of symptoms amongst cancer patients attending palliative care in two African countries. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:51-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Selman LE, Higginson IJ, Agupio G, et al. Quality of life among patients receiving palliative care in South Africa and Uganda: a multi-centred study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ministère de la santé RDC. Rapport narratif: Profil pharmaceutique de la République Démocratique du Congo 2011 [in French]. Available online: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/coordination/drc_pharmaceutical_profile.pdf

- Kingham TP, Alatise OI, Vanderpuye V, et al. Treatment of cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e158-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manzambi K, Eloko EM, Bruyère O et al. Financement de la santé et recouvrement des coûts en République Démocratique du Congo: le lourd fardeau des ménages [in French]. 2014. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2268/170885

- Monde.fr., La RDC au dernier rang de l'indice de développement humain du PNUD [in French]. 2013. Available online: http://www.lemonde.fr/planete/article/2013/03/15/la-rdc-au-dernier-rang-de-l-indice-de-developpement-humain-du-pnud_1849284_3244.html#zHZ83fDROekU3KJ3.99

- Kunda J, Fitzpatrick J, Kazwala R, et al. Health-seeking behaviour of human brucellosis cases in rural Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2007;7:315. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weeks L, Balneaves LG, Paterson C, et al. Decision-making about complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients: integrative literature review. Open Med 2014;8:e54-66. [PubMed]

- Henoch I, Lövgren M, Wilde-Larsson B, et al. Perception of quality of care: comparison of the views of patients' with lung cancer and their family members. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:585-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lawson M. Palliative sedation. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2011;15:589-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kikule E. A good death in Uganda: survey of needs for palliative care for terminally ill people in urban areas. BMJ 2003;327:192-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Villiers M, Maree JE, van Belkum C. The influence of chronic pain on the daily lives of underprivileged South Africans. Pain Manag Nurs 2015;16:96-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ministère du plan RDC. Deuxième enquête démographique et de santé (EDS-RDC II 2013-2014) [in French]. 2014. Available online: pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pbaaa437.pdf

- Powell RA, Namisango E, Gikaara N, et al. Public priorities and preferences for end-of-life care in Namibia. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:620-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertrand E, Muna WF, Diouf SM, et al. Cardiovascular emergencies in Subsaharan Africa. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 2006;99:1159-65. [PubMed]

- Lewington J, Namukwaya E, Limoges J, et al. Provision of palliative care for life-limiting disease in a low income country national hospital setting: how much is needed? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2012;2:140-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rawlinson F, Gwyther L, Kiyange F, et al. The current situation in education and training of health-care professionals across Africa to optimise the delivery of palliative care for cancer patients. Ecancermedicalscience 2014;8:492. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ministère du plan RDC. Enquête Démographique et de santé (EDS-RDC) [in French]. 2007. Available online: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR208.pdf