Spirituality in adolescent patients

Spirituality as part of palliative care for adolescent patients

Inclusion of spirituality as a care domain represents not just a best practice in palliative care, but a defining professional obligation. Inclusion of spiritual health screenings as a standard of care recognizes each patient’s right to spiritual wellness regardless of age or diagnoses. The World Health Organization definition of palliative care includes emphasis on integration of “spiritual aspects of patient care” (1). Spiritual care is included as one of the eight core clinical practice domains according to The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (2). The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations recommends assessment of spiritual care for patients as part of healthcare encounters (3). Further, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, outlines a child’s right to a sense of spiritual well-being: “to develop physically, mentally, morally, spiritually and socially in a healthy and normal manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity” (4). Professional chaplains working in palliative care have an additional specialty certification path available for Board Certified Chaplains that includes 37 competencies demonstrated in written work and before a committee of certified peers (5). The fact that professional chaplaincy certifying bodies take palliative care certification seriously enough to offer additional specialty certification highlights the importance that professional spiritual care professionals place on excellence in palliative care. Whole-person care necessarily includes attentiveness to not only physical wellbeing but also emotional, psychosocial, and spiritual health. And yet, despite this recognized professional importance, health care team members (6), families (7), and even adolescent patients themselves (8) recognize that spiritual/religious assessments and interventions as an unmet need. Barriers cited for spiritual care being an unmet need among adolescent patients include knowledge gaps and lack of staff training, staff discomfort and fear of offending, and lack of funding or staffing for pastoral care departments (9).

Spirituality described by adolescents

The formation of meaning and morality marks adolescent years. Arguably, the primary task of adolescent years is to determine actualization and to recognize self in relation to others (10). Identity-finding has been depicted by Erik Erikson as the main task of adolescence as a life stage (11). Jean Piaget recognized adolescent years as a time of formal operational thinking, marked by abstract thought and hypothetical reasoning (12). Leading faith development theorists describe the adolescent years marked by the need to operationalize their faith/beliefs lived out through their experience. Theorists describe teenagers beginning a “personal journey” (13), finding dissonance between learned belief system and experience (14), believing only what is validated through experience (15), or as David Elkind notes that adolescence is marked by developing an independent system of belief that attempts to answer the questions experience forms in dissonance to that which was initially conceived and begins to form and operationalize a spirituality, and morality, that is their own (16). Therefore, teenagers are primarily tasked with incorporating their past while also projecting their future: a most meaningful pursuit (17). Spirituality among adolescents has been described in terms of wisdom, connectedness, joy, wonder, moral sensitivity, and compassion (18). In a German study inclusive of over 250 adolescents, conscious interactions, compassion/generosity, and aspiring for wisdom were the most highly valued aspects of spirituality (19). Pursuit of meaning allows adolescents to make sense of the world around them and to function experientially in that world. In that spirituality is broadly defined as a human search for meaning, spirituality may thus be considered a universal experience for adolescents.

The helps and harms of spirituality for adolescents with life-limiting illness

Fowler, a father of theory of faith development theory, found most adolescents to be in what he termed a synthetic-conventional faith stage (20). According to Fowler, positive and negative experiences cause adolescents to examine their faith and possibly question the beliefs of their family or community (20). This exploration often leads the adolescent to form personal faith and beliefs, which either reject or confirm family and community faith. In addition, Elkind observes that the adolescent’s construction of one’s own morality separate from “conventional” standards is very present at this time and will continue throughout the life span (16). The impact of a life-limiting illness at this critically important stage of faith/belief development is not to be dismissed and instructs palliative care providers to pay close attention to this particular dimension of care.

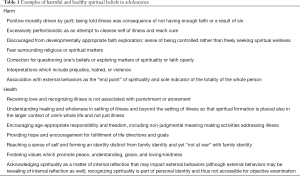

Adolescents with life-limiting illness have the double-impact of determining meaning in life while also placing their diagnoses within the context of a meaningful life. Thoughts regarding the afterlife become more pressing and more chronologically urgent when someone is faced with a terminal diagnosis at a young age. While most adolescents are moving from a conventional system of belief that is inherited and beginning to question more abstractly and operationalize a forming personal theology through lived experience, adolescents with a life-limiting illness will do this work in the context of that experience. The nature of suffering and the concept of fairness/just world becomes real and quickly real when an adolescent experiences pain crisis. In fact, spiritual pain may manifest as physical pain just as physical pain may result in spiritual pain. Adolescents with illness find themselves in a liminal space that is not easily or cleanly dealt with. The usual things that teens would bounce ideas off of (beliefs of religious institutions, beliefs of parents, teachers, peers, etc.) now is complicated by questions that most, even those more spiritually mature, have difficulty or comfortability addressing. This leaves adolescents needing palliative care services very vulnerable spiritually. Adolescents with illness may be vulnerable to fears, concerns, and guilt overcoming their spiritual journey. Illness may realistically subvert an adolescent’s sense that the world is a safe and caring place. Adolescents with illness may thus be considered vulnerable to spiritual harm, warranting special attentiveness to spiritual health (Table 1). Some adolescents with illness reveal immense wisdom, beyond their chronological years, and others reveal spiritual regression. Palliative care teams bearing witness to suffering and offering a peaceful presence can be a healing force for adolescence grappling with the search for meaning in the context of illness.

Full table

The importance of differentiating spirituality from religion for adolescents

The essential distinction between spirituality and religion is particularly important when caring for teenage patients. Religion is defined as teachings and practices of established faith traditions, organized religious groups, or institutions (10). Traditional religion may help some adolescents define their worldview and may offer ritual, framework, and moral code. Spirituality may or may not include elements of traditional religion. Adolescence represents a time of questioning, trying on new worldviews, potentially challenging or reconsidering old worldviews, and possibly circling back to the prior held views but now in a more informed and owned manner. Adolescence represents a time of transition toward independence and a shift in decisional-locus from strict reliance on parental control toward self-actualization. Adolescence may thus be a time of shifting away from or closer to a family’s religion or a community’s held beliefs. How this seeking and searching is experienced and expressed during adolescence varies according to cultural, religious, and social norms.

As part of their developmental experience, adolescents are prone to thinking in terms of social groupings and self within the context of groups. Thus, an adolescent who may secretly question certain teachings that define his family’s religion may feel isolated. An adolescent who holds differing political views from her parent’s organized religion may feel silenced. Adolescents may carry immense struggle and questions, but may worry that verbalizing or pondering these questions may “undue” their role as religious or their portrayal as faithful. This adolescent may even feel that he or she is no longer “spiritual” due to internal grappling, questions, and spiritual struggles. A time of questioning may be considered common, healthy, and even formative for an adolescent’s spiritual formation. But, the time of questioning may be felt as isolating or alienating by the adolescent, as depicted in case example 1.

Case example 1

A 13-year-old female with osteosarcoma told the hospital chaplain that her faith teaches God is love, but, she questioned God’s love for her at the time of her leg amputation. She did not understand how a loving God could allow her to lose her leg and her identity as an avid tennis player. She felt that she could not share this questioning with her parents lest they fear she was doubting the family’s long-held faith. Her parents were praying for a miracle. She didn’t want to attend church anymore, but, attended because she did not want to disappoint her parents or stand in the way of their pursuit of divine intervention. The adolescent stated she thinks she is not spiritual because she doesn’t know if God loves her. By helping the adolescent to explore these questions in terms of spiritual meaning (identity beyond tennis playing, role of suffering, definitions of love, recognition of loss and grief, hopes), the hospital chaplain enabled a safe space for the adolescent to grow into her own faith by recognizing her family’s God may be large enough to handle her questions and even her anger.

The legitimate faith questions that were brought forth by this young patient seemingly, from her vantage point, put her at odds with the faith of her parents. The dissonance that she perceives creates spiritual distress through feelings of isolation, alienation and even shame depending on how the patient interprets the response of those around her. A professional chaplain would seek to explore these questions, empower the patient to explore these questions openly and deeply without judgment, attempt to create dialogue with faith of origin, and provide creative ways to operationalize newly forming beliefs based on her current lived experience. One potential intervention might be the utilization of the “Feeling Hearts” game (available through Grief Watch) in which the chaplain places clay hearts on a table of different colors and textures and ask the patient to pick the heart that represents how they are feeling at the moment. The chaplain than uses multiple questions to explore questions, empower the patient, and operationalize new thoughts or beliefs.

Adolescent spirituality within cultural context

Adolescence, the period of transition from childhood to adulthood, as a life phase is relatively new in global history and heavily nuanced by culture and social norms (21). Even the years of adolescent vary by global location, as locations with shorter life expectancy tend toward shorter or younger “adolescence” chronologically. Many religious communities have rites of passage for adolescence, such as confirmation in the Catholic tradition; bar or bat mitzvah in Judaism, Ritushuddhi and Upanayana for Dvija in Hinduism. The expectations of adolescents are often influenced by custom and tradition, but there stands a human propensity toward responsibility for personal spirituality (not just family spirituality) and ownership of perspective during adolescents (21).

Adolescent spirituality within familial context

Whether an adolescent’s family prays together, attends faith services, engages in religious rituals, or acknowledges a Holy all contextualize an adolescent’s spiritual worldview. An effective assessment of an adolescent’s spirituality does not assess in isolation, but takes into account the entire family system. As depicted by Brooks and Ennis-Durstine: “It weakens the effectiveness of the child’s narrative as a means to assist the child (or adolescent) if we do not understand how other family members narratives may either subvert or overpower the child’s (17).” Adolescent spirituality is ideally assessed as the child’s spirituality within a recognized larger landscape of family and community spirituality.

For those parents who identify religion, spirituality, or life philosophy as relevant and accessible for discussion (22), palliative care teams ideally assess and address the family’s needs as part of comprehensive care of the adolescent. An adolescent’s illness impacts parent, grandparent, and sibling spirituality (23,24). A survey of primary parental caregivers of children/adolescents referred to palliative care at an urban, pediatric academic medical center in the United States revealed that less than half received spiritual assessment but the majority would have wanted a spiritual assessment (25). Palliative care ideally reaches the family unit in a way that is meaningful and supportive for the family’s overall connectedness and coping (26). Adolescents with illness often strive to be positive or upbeat for their family members; adolescents thus feel personally helped when they realize the care team is also focused on caring for their family members (27).

Narrative literature review on adolescent spirituality

The adult-based literature has investigated the relationship between spirituality, perceived quality of life, hope, health, and patient satisfaction (28); whereas, adolescent-based studies on spirituality and wellness domains are less prevalent. The study team conducted a narrative review of the topic of spirituality in adolescents using PubMed and EBSCOHost with search terms “adolescen*” and “spiritual*” inclusive of years 2000-2016. Based on the findings from this search, Table 2 offers recommendations for future research.

Full table

Based on the current evidence-base, spirituality is recognized to correlate with depressive symptoms (29) and health-risk behaviors (29) to include substance abuse (30,31) during adolescent years. Qualitative study literature base has revealed that spirituality is recognized as important among adolescents living with cancer (32). Based on findings from a longitudinal study of 128 patients with diabetes or cystic fibrosis, positive spiritual coping may serve as a buffer from developing depression and maladaptive coping strategies for adolescents living with these chronic illnesses (33). Spiritual wellbeing and working through spiritual struggle have been associated with adjustment in adolescent cancer survivors (34). Interestingly, a latent profile analysis study of adolescent with HIV showed significantly higher social health related quality of life among the highest overall religious/spiritual adolescent group with HIV (35). A study of forty-five adolescent patients with cystic fibrosis recognized lower ‘spiritual struggle’ and greater ‘engaged spirituality’ ultimately as predictors of treatment adherence (36).

Change as a constant in adolescence

The adolescent years are defined by the World Health Organization as ages 10–19 years (37). The reality is that lived adolescence is defined less by years and more by the constancy of change: biological, neurocognitively, and psychosocially. Each of these change domains impacts and informs adolescent spiritual development.

Biological changes

Biologically, clinicians consider adolescence as the phase surrounding puberty. The order of the physiological changes is relatively universal for humans experiencing the transition from childhood to adulthood. But, the speed and timing of these changes vary according to hormonal determination. A complex array of inter-related and sometimes competing hormones drives the body through incredible physical changes. Sudden height spurts, shifts in muscle mass and body fat distribution, voice changes, development of secondary sexual characteristics, and dermatological drama (also known as acne) occur. While the order of physical changes can be relatively predictable based on expected biological pathways, the physiology of adolescence is impacted by lived experiences, as inadequate nutrition, chronic illness, and social stress impact the timing and speed of expected physical changes. Thus, even the biology of adolescence is a highly individualized experience.

Biological changes’ relevance to spiritual development

Adolescents depict that the variance in timing of physical changes among same-age peers and classmates can result in bullying, teasing, and even peer pressures (38). There is immense social pressure surrounding biological changes (39), which may stunt or speed spiritual development. Thus, palliative care teams are prudent to talk openly with adolescents about where they consider themselves in the longitudinal trajectory of development (physical, social, psychological, and spiritual) and to normalize the uniqueness of each human’s journey through this developmental timeframe. Adolescents may feel new conflict between their church, mosque, temple, or synagogue’s teachings regarding sanctity of sexual relations and their raging hormones. For example, an adolescent male described the pressure to consume more protein for muscle mass conflicting with his family’s religious teaching on vegetarian lifestyle. Care teams should be open to hearing how adolescents feel their body and hormones may support or challenge their faith lives. Teams should not make assumptions about biological development matching the timeline of other developmental tasks. An adolescent with an adult-body may still feel childlike in his or her spiritual development, whereas an adolescent with pre-pubertal appearance may feel he or she has reached spiritual maturation through formative life experiences.

Neurological changes

Neurologically, significant developments take place in the limbic system and pre-frontal cortex during adolescent years. Even the amount of white matter in the brain increases through myelination as synaptic pruning occurs among grey matter. Thus, the risk-weighing, pleasure-seeking, reward-processing, emotion-regulating, future-planning, impulse-controlling and decision-making centers of the brain are undergoing neurodevelopmental changes. Further, the level of neurotransmitters (primarily dopamine and serotonin) change during adolescent years, possibly explaining the emotional and mood changes common in adolescents. Sleep-wake cycles and regulation shift during adolescents. Puberty marks a transition in risks for mental health disorders such as depression, substance abuse disorders, and psychosomatic symptoms (40). Recent research has recognized that the exploration and experimentation common to adolescents has grounding in neuronal and neurocognitive developments.

Neurological changes’ relevance to spiritual development

Adolescents may feel that their shifts in moods are not congruent with their best self. They may experience anger in more intense ways secondary to increased testosterone or sadness in the setting of progesterone peaks. Adolescent are sometimes surprised by their own impulsivity or risk-taking. Adolescents may benefit from conversations regarding hormonal influence while focusing on healthy boundaries and development of moral compass. By helping adolescents learn more about their bodies and anticipated changes, palliative care teams can help adolescents adjust and avoid potential relationship problems (such as, healthy sleep habits leading to healthier morning communication with parents). Some adolescents may benefit from mental health referrals in addition to chaplain referrals for additional support.

Cognitive and psychosocial changes

Cognitive and psychosocial changes during adolescence include ability to engage in abstract thinking, increased attention, longer memory span, quicker processing speed, and metacognition (thinking about thinking). Adolescents are less bound by concrete realities and can contemplate hypothetical scenarios outside of what currently or physically exists.

Cognitive and psychosocial changes’ relevance to spiritual development

Adolescents who previously held certain teachings as dogma may suddenly experience internal debate or questions. Adolescents may experience relativistic thinking, question of assertions, and frustration with what maybe had been presented to them as “fact”. Care teams can be a safe space where adolescents can question aloud the nature of illness or the afterlife. Rather than offer platitude responses, care teams can refer to professional chaplains familiar with the palliative care context. Adolescents may benefit from knowing their questions are a form of growth and understanding. As capacity for abstract intellectual thought and reasoning enhance, moral thinking becomes a more prominent consideration and opportunities to operationalize these evolving becomes paramount. As adolescents begin to take other people’s perspectives into consideration, particularly as peer opinion becomes meaningful to adolescents, providing opportunities to bounce ideas safely off of professionals in a peer setting can be very helpful. Adolescents are consolidating their sense of self while they are forming their sense of community and belonging. Adolescents may thus benefit from group support and safe peer discussions.

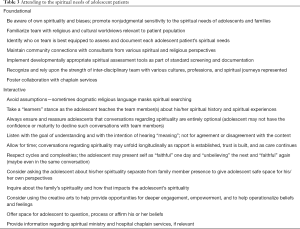

Clinical implications for adolescent patients’ palliative care teams

Astute palliative care teams recognize that adolescence is a time of transition. The impact of managing a life-limiting illness while forming one’s identity as an adolescent is exponential. To attend to the psychological and spiritual health of adolescent patients has far-reaching consequences for the patient and the family. Table 3 provides recommendations for palliative care teams in this regard.

Full table

Conclusions

Adolescence, by definition, represents a time of change and formation. Often faith, beliefs, hopes, joys, values, and meanings become personalized rather than projected by others during the adolescent life stage. Thus, adolescents with illness benefit from presence of caring providers who are trained to offer nonjudgmental listening, thoughtful questions, and gentle guidance. Adolescents deal with universal spiritual issues when they try to make sense of the rapid changes occurring during their own development and during their own diagnoses. Questions which often arise for adolescent patients include those related to meaning, purpose, fairness, potential for higher power, nature of suffering, etiology of pain or illness, and the afterlife. Identity and meaning often gain increasing importance for adolescents with illness. Palliative care teams are privileged to care for the whole-rapidly-changing-person (the adolescent patient): body, mind, and even psyche, soul, and spirit.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. Palliative Care. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed August 28 2016.

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hodge DR. A template for spiritual assessment: a review of the JCAHO requirements and guidelines for implementation. Soc Work 2006;51:317-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx. Accessed August 28 2016.

- Association of Professional Chaplains. Cited 2016 October 26. Available online: http://bcci.professionalchaplains.org/content.asp?admin=Y&pl=45&sl=42&contentid=49

- Feudtner C, Haney J, Dimmers MA. Spiritual care needs of hospitalized children and their families: a national survey of pastoral care providers' perceptions. Pediatrics 2003;111:e67-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bousso RS, Misko MD, Mendes-Castillo AM, et al. Family management style framework and its use with families who have a child undergoing palliative care at home. J Fam Nurs 2012;18:91-122. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv 2012;6:239-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McNeil SB. Spirituality in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer: A Review of Literature. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2016;33:55-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sexson SB. Religious and spiritual assessment of the child and adolescent. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2004;13:35-47. vi. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Erikson EH. editor. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York, NY: WW Norton, 1980.

- Piaget J. editor. The Equilibration of Cognitive Structures: The Central Problem of Intellectual Development. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- Powers BP. editor. Growing Faith. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1982.

- Westerhoff, John H. editors. Bringing Up Children in the Christian Faith. Minneapolis: Winston Press Inc., 1980.

- Stephens LD. editor. Building a Foundation For Your Child's Faith. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996.

- Elkind D. The origins of religion in the child. In: Spilka B, McIntosh DN. editors. The psychology of religion. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997:97-104.

- Brooks J, Ennis-Durstine K. Faith, Hope, and Love: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Providing Spiritual Care. In: Wolfe J, Hinds P, Sourkes BM. editors. Textbook of Interdisciplinary Pediatric Palliative Care. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2011:111-8.

- Michaelson V, Brooks F, Jirasek I, et al. Developmental patterns of adolescent spiritual health in six countries. Social Science and Medicine: Population Health 2016;2:294-303.

- Büssing A, Hirdes AT, Baumann K, et al. Aspects of spirituality in medical doctors and their relation to specific views of illness and dealing with their patients' individual situation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:734392. [PubMed]

- Fowler JW. editor. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development in the Quest for Meaning. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row, 1981.

- Roehlkepartain EC, Benson PL, Scales PC, et al. With their own voices: A global exploration of how today's young people experience and think about spiritual development. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Search Institute, 2008.

- Hexem KR, Mollen CJ, Carroll K, et al. How Parents of Children Receiving Pediatric Palliative Care Use Religion, Spirituality, or Life Philosophy in Tough Times. J Palliat Med 2011;14:39-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies B, Brenner P, Orloff S, et al. Addressing spirituality in pediatric hospice and palliative care. J Palliat Care 2002;18:59-67. [PubMed]

- Schneider MA, Mannell RC. Beacon in the storm: an exploration of the spirituality and faith of parents whose children have cancer. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 2006;29:3-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelly JA, May CS, Maurer SH. Assessment of the Spiritual Needs of Primary Caregivers of Children with Life-Limiting Illnesses Is Valuable Yet Inconsistently Performed in the Hospital. J Palliat Med 2016;19:763-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meert KL, Thurston CS, Briller SH. The spiritual needs of parents at the time of their child's death in the pediatric intensive care unit and during bereavement: a qualitative study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005;6:420-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weaver MS, Baker JN, Gattuso JS, et al. "Being a good patient" during times of illness as defined by adolescent patients with cancer. Cancer 2016;122:2224-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Richardson P. Assessment and implementation of spirituality and religiosity in cancer care: effects on patient outcomes. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:E150-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cotton S, Larkin E, Hoopes A, et al. The impact of adolescent spirituality on depressive symptoms and health risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health 2005;36:529. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Debnam K, Milam AJ, Furr-Holden D, et al. The Role of Stress and Spirituality in Adolescent Substance Use. Subst Use Misuse 2016;51:733-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DuRant RH. Adolescents' spirituality and alcohol use. South Med J 2007;100:341-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamper R, Van Cleve L, Savedra M. Children with advanced cancer: responses to a spiritual quality of life interview. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2010;15:301-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reynolds N, Mrug S, Hensler M, et al. Spiritual coping and adjustment in adolescents with chronic illness: a 2-year prospective study. J Pediatr Psychol 2014;39:542-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park CL, Cho D. Spiritual well-being and spiritual distress predict adjustment in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lyon ME, Kimmel AL, Cheng YI, et al. The Role of Religiousness/Spirituality in Health-Related Quality of Life Among Adolescents with HIV: A Latent Profile Analysis. J Relig Health 2016;55:1688-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grossoehme DH, Szczesniak RD, Mrug S, et al. Adolescents' Spirituality and Cystic Fibrosis Airway Clearance Treatment Adherence: Examining Mediators. J Pediatr Psychol 2016;41:1022-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Development. 2016. Available online: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/en/

- Hamlat EJ, Shapero BG, Hamilton JL, et al. Pubertal Timing, Peer Victimization, and Body Esteem Differentially Predict Depressive Symptoms in African American and Caucasian Girls. J Early Adolesc 2015;35:378-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Negriff S, Brensilver M, Trickett PK. Elucidating the mechanisms linking early pubertal timing, sexual activity, and substance use for maltreated versus nonmaltreated adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:625-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patton GC, Viner R. Pubertal transitions in health. Lancet 2007;369:1130-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]