The development of palliative care for dementia

Palliative care, which is the basis of hospice care, was originally developed for patients with terminal cancer. In 1967, Cecily Saunders recognized that continuation of aggressive medical intervention with toxic chemotherapeutic drugs may not be in the best interest of a patient, because of the low probability that the chemotherapy will significantly prolong life. She established the first purpose-built hospice and suggested that emphasis should be placed on the quality of remaining life instead of on prolongation of life at all costs. Her goal was adding life to days instead of days to life.

Alzheimer’s disease and other progressive dementias have not been considered as appropriate diagnoses for hospice care because they were not once recognized as terminal diseases. Until 1980’s, many patients with advanced dementia were cared for in nursing homes, where the emphasis was on prolongation of life. This goal of care resulted in frequent transfers of residents from nursing homes to hospitals, use of feeding tubes for persons with eating difficulties, and frequent use of restraints for the “safety” of the residents. Care for patients with advanced dementia posed a dilemma for attending physicians, who questioned the use of aggressive medical intervention for these debilitated persons. This dilemma was eloquently described by Hilfiker (1).

When Hilfiker was called in the middle of the night to see a patient with advanced dementia who had developed a fever, he was faced with a dilemma. He diagnosed that the patient had pneumonia and had to decide whether to send her to a hospital or treat her in the nursing home. The hospital would provide aggressive treatment, “toxic antibiotics,” intravenous hydration, and more “heroics” that would potentially cure her pneumonia but could cause significant discomfort and agitation. Because he had known the patient for many years since before her dementia, Hilfiker’s “human sympathies” told him that the patient had a desire to die. He decided to forgo transfer to the hospital and treat her in the nursing home, which would be more comfortable for her, but may not cure her pneumonia. Hilfiker reflected that physicians make these kinds of decisions daily with neither appropriate training nor the resources to make these decisions alone.

Establishment of a dementia special care unit (DSCU) as part of the Geriatrics Research Education and Clinical Center at the E.N. Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital in Bedford, Massachusetts, provided an opportunity to address Hilfiker’s dilemma. In 1985, our team, consisting of a physician, nurse practitioner, social worker, head nurse, and chaplain developed a palliative care program for residents of the DSCU. The treatment dilemma was avoided by making an advance proxy plan for each resident (2). We conducted conferences that included the treatment team and family members and friends of the residents. The families were informed that advanced dementia is a terminal disease, for which comfort may be more important than prolongation of life at all costs. The team presented treatment options and discussed the benefits and burdens of each course of action. The treatment options included cardiopulmonary resuscitation, transfer to an acute care setting, treatment of generalized infections with antibiotics, and tube feeding. We were always able to reach a consensus with the family members based on the resident’s previous wishes or resident’s best interests as perceived by the family.

Initial family conferences resulted in all residents having do not resuscitate (DNR) status, almost all refusing transfer to an acute care setting, and more than half refusing tube feeding and antibiotic treatment for generalized infections (3). Research conducted with this resident population showed limited effectiveness of antibiotic treatment for generalized infections (4), minor effect of eating difficulties on survival (5), and improved comfort of residents treated with this palliative approach compared to traditional care (6). In addition to improved comfort, our palliative approach also saved health care resources (7). These and other research studies required development of several scales that can be used for research involving persons with dementia (8).

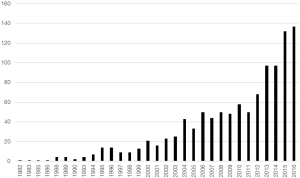

Since that time, research on palliative care for dementia patients has exploded (Figure 1). This research was stimulated by the increasing prevalence of dementia and by the extension of the US hospice program to residents of nursing homes with a diagnosis dementia. Palliative care for persons with dementia is included in several clinical practice guidelines and it was described in detail in the White Paper released by the European Palliative Care Association (9).

This special issue of Annals of Palliative Medicine presents articles describing the current state of palliative care for dementia in Europe and North America. An article by Lloyd-Williams et al. summarizes epidemiological data about dementia in the UK and points out that many people also have other illnesses and disabilities in addition to their dementia. They stress the importance of advance care discussions for end-of-life care. The importance of advance care planning is also stressed by Ryan et al., who conducted a review of qualitative literature addressing the advance care planning (ACP) experiences of people with dementia, family caregivers and professionals. They point out the difficulties related to the timing of ACP caused by uncertainty about length of survival of people with dementia, and find that families of people affected by dementia prefer informal approaches to ACP planning. Their review also suggests that it is important to increase the knowledge of professionals, as well as people with dementia and families, to increase the practice of formal future planning.

Larkin’s article points out the need for research in palliative care concerning care pathways, outcome measures, cost-effectiveness, and supportive technologies. He concludes that we need more information about the integration of palliative dementia care and evaluation of which quality indicators exist or can be adapted or applied from other areas such as cancer care. Hockley’s presentation stressed the need for specialized approaches for palliative care in dementia because it is different from palliative care in cancer. An article by Gove et al. discusses uncertainty about timing of palliative care in dementia. The EAPC White Paper (9) showed that there is no agreement about when to initiate palliative care in dementia and this is one of the barriers to application of palliative care for people with dementia. Other barriers to palliative care in dementia were identified by the literature search by Erel et al.

The need for palliative care and its application to dementia care is presented by Hradcová, using two case reports. One of them involves eating difficulties and the other one disruptive vocalization. She describes how eating can be improved by providing individualized palliative care from a dedicated caregiver. An improvement of nutrition for people with dementia using texture modified food, their acceptance by residents and feasibility for care staff, is described by Austbø Holteng et al. Palliative care may require a hospital stay even though acute care hospitals are not optimal settings of care for people with dementia. Kabelka describes the improvement of quality of life of people with dementia who received multidisciplinary evaluation in a hospital. Hospitalization was also used as a strategy for management of disruptive vocalization described by Hradcova. However, the report does not provide information about success of this management strategy. In contrast, Simard’s article provides information about successful non-pharmacological management of disruptive vocalization using the Namaste Care approach.

Namaste Care is described in detail by Stacpoole et al. She presents features of the program and changes that were seen after its introduction, obtained from interviews of the staff and residents’ families. Favorable results of implementation of Namaste Care in care homes stimulated St John and Koffman to introduce Namaste into an acute care hospital. Interviews with care provider and families in that setting indicated that Namaste Care was well received by the study participants and was considered to improve well-being and reduce agitation, with patients appearing more calm and relaxed after participating in the program. There were some barriers to implementation of Namaste Care in a nursing home, which are described by Hunter et al. However, Namaste Care has been implemented all over the world, which indicates that these barriers can be overcome.

Successful provision of palliative care for persons with dementia is sometimes hindered by misunderstanding of the nature of palliative care. Some may consider it appropriate only at the end of life during dying, and some may consider its main goal to be elimination of inappropriate aggressive medical interventions. Palliative care meets both of these objectives, but its main goal is improving life of the person with dementia and his/her care providers, both formal and informal. That is why some believe that palliative care is needed at the time of dementia diagnosis, when both the patient and his/her family need support to deal with this diagnosis. In the later stages of dementia, palliative care should not only avoid burdensome and ineffective medical interventions, but should also provide environment and activities that improve quality of life of people with dementia. Maintaining quality of life despite dementia progression is a difficult, but possible task, as demonstrated by the Namaste Care program (10).

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Hilfiker D. Sounding Board. Allowing the debilitated to die. Facing our ethical choices. N Engl J Med 1983;308:716-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hurley AC, Bottino R, Volicer L. Nursing role in advance proxy planning for Alzheimer patients. Caring 1994;13:72-6. [PubMed]

- Volicer L, Rheaume Y, Brown J, et al. Hospice approach to the treatment of patients with advanced dementia of the Alzheimer type. JAMA 1986;256:2210-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fabiszewski KJ, Volicer B, Volicer L. Effect of antibiotic treatment on outcome of fevers in institutionalized Alzheimer patients. JAMA 1990;263:3168-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Volicer L, Seltzer B, Rheaume Y, et al. Eating difficulties in patients with probable dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1989;2:188-95. [PubMed]

- Hurley AC, Volicer B, Mahoney MA, et al. Palliative fever management in Alzheimer patients. quality plus fiscal responsibility. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1993;16:21-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Volicer L, Collard A, Hurley A, et al. Impact of special care unit for patients with advanced Alzheimer's disease on patients' discomfort and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:597-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Volicer L, Hurley AC. Assessment Scales for Advanced Dementia. Baltimore: Health Professions Press, 2015.

- van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2014;28:197-209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simard J. The End-of-Life Namaste Program for People with Dementia. 2nd ed. Baltimore, London, Sydney: Health Professions Press, 2013.