“Living in the moment” among cancer survivors who report life-transforming change

Introduction

In the course of coping with very adverse medical conditions, patients can encounter challenges too great to entirely self-manage (1). Overwhelming challenges associated with adverse medical conditions sometimes result in the loss of valued abilities to engage satisfyingly in personal life (2). This is one definition of being functionally “wounded”, and it is related to the concept of “total pain” developed by Dame Cicely Saunders (3). The practice of palliative medicine can be structured to provide effective supportive care for patients who are functionally wounded in this way. When a patient partially or fully gains restoration of valued abilities to function as a person (4), this significant outcome can be defined as functional “healing” in palliative care. Functional healing can occur through multiple pathways, from secular resilience (“bouncing back”) to spiritual support.

Some palliative care practitioners are quite effective at promoting functional healing among functionally wounded patients despite an incomplete scientific basis for some of their methods. Their effectiveness indicates that the mechanisms of the functional healing process could be naturally occurring phenomena that are quite suitable for scientific study, but not yet generally understood and measurable in scientific terms. The functional healing methods of these effective palliative care practitioners are often labeled as involving “spirituality.” Unfortunately, this is a term that is generally associated with personal beliefs and not with the mechanisms of phenomena of nature that are the domain of science (5). We have observed that the label “spirituality” tends to distance many physicians from effective methods of functional healing for patients under duress.

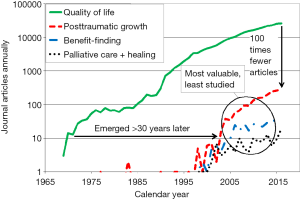

Highly positive subjective outcomes during highly stressful circumstances are greatly valued by patients who have experienced them, yet they are among the least studied (see Figure 1). Folkman was one of the first to provide strong empirical evidence indicating that positive subjective outcomes are a phenomenon distinct from negative subjective outcomes: positive and negative subjective outcomes are not merely two sides of one phenomenon (6-8). She studied the coping mechanisms of care-giving partners of AIDS patients at a time in the history of AIDS when the epidemic was strong and no effective treatments were available. The participants in her studies said that to understand how they coped while caring for their dying partners, the study would have to capture their positive subjective experiences as well as their obvious negative subjective experiences. To a significant degree, positive outcomes can co-occur with negative outcomes, and that attribute makes possible the facilitation of positive outcomes even during very adverse medical conditions.

We needed a descriptive phrase to enable recruitment of cancer survivors who have experienced very positive subjective outcomes during diagnosis, treatment or recovery. The caregivers on our team (who are highly experienced in providing supportive care to cancer patients) coined the phrase “life-transforming change” (LTC) to encompass exceedingly positive subjective outcomes which occur in the context of a life-altering or life-threatening medical condition. This phrase sets a high threshold for participation in this study. We acknowledge that many genuine but less transformative experiences of personal growth will not meet the high threshold set by this phrase. LTC can occur among patients as they seek to counter adversity. In a previous article, we determined the process of LTC appeared to represent a pragmatic and long-lasting adjustment to a life-threatening condition, and found it to be related to meaning and spirituality (9). In this article, we probe how well the positive items being considered for the 1st edition of the PROMIS Psychosocial Impact of Illness (PII) item bank were capturing highly positive outcomes, the most desired outcomes.

Method

Prior to this study, there has been no established theory of LTC. As in our previous article from this study, we used a grounded theory approach. All participants regarded their LTC condition as a phenomenon that was completely unexpected in the context of cancer, and as having high personal value and benefit. In this article, we seek to further understand LTC by analysis of participants’ numerical and verbal evaluations of psychosocial questionnaire items on positive subjective outcomes.

Assessment items and themes

We obtained the 2008 v1 set of 67 positive psychosocial questionnaire items from the PII item bank development team of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information Systems initiative (PROMIS; http://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php and http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis/list-of-adult-measures). The 67 items are listed in the Table S1. This set of items had been carefully selected by the PII team to capture a broad range of psychosocial outcomes, and the items are sourced from a variety of instruments. It was very important to us that the set of items used in this study should represent more than one theory of personal growth (positive psychosocial outcomes).

Full table

Our goal was to rank the frequency and importance of themes, not assess psychosocial state. Therefore, PII item calibration was not relevant to our study. The set of PII items were provided to us in prior to final selection, calibration, and release as a PROMIS assessment tool consisting of 39 items (https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS%20Psychosocial%20Illness%20Impact%20Positive%20Scoring%20Manual.pdf).

The 67 positive items were categorized in four sub-domains as defined by PROMIS research staff: self-concept (16 items), social impact [19], stress response [15], and spiritual/existential [18]. Some of these 67 items were variations in wording on the same concept as other items, and some participants expressed concerns that there were repetitions among the items. After all interview sessions were completed, the PII items were grouped into 20 researcher-selected conceptual themes (the theme assigned to each of the 67 items is listed in the right-hand column of the PII item Table S1). Average scores for each theme were computed and compared.

Most of these 20 themes have relatively obvious correspondence between the theme name and the items in the theme. The theme of “living in the moment” (LITM) is the focus of this article. Our criteria for assigning items to the “LITM” theme were (I) disengagement from both anticipatory and recalled concerns; (II) taking stock of the full spectrum of what the present timeframe has to offer; and (III) favoring positive experiences in the present to the degree that it is possible to do so comfortably. The items in this theme are not based on creating an optimistic attitude or hedonistic pleasure-seeking.

For example, the PII item “My illness has helped me appreciate each day more fully” was included in this theme because the item specifies “each day”—a reference to the present time frame. However, the item “My illness has given me a greater appreciation for life” was placed in the “Appreciating health/life” theme because it reflects a much broader span of time. As another example, the item “My illness has helped me be less easily bothered by little things” was also included in this theme because it involves putting little things in perspective, disengagement from anticipatory or recalled concerns, and directing attention away from subjectively negative experiences in the present.

Recruitment, consent and screening

The protocol for the research project was approved by the NIH IRB (protocol number 09-CC-0227), and it conforms to the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration (revised 2013). Eight cancer survivors were identified by a non-profit holistic support organization offering psychological, social, and spiritual support to cancer survivors in the greater Washington, DC area. One additional cancer patient was identified through a non-profit hospital in the greater Washington, DC area, for a total of nine participants. The head of supportive care at each organization informed candidates that this study existed and asked if the candidate might be interested. Interested candidates were given an information packet including the informed consent form, and assured that the care and services they receive at the host organization would not be influenced by participation or non-participation in this study. Each of the nine candidates gave informed consent for participation.

Each face-to-face, private session consisted of the following sequential elements: answering the participant’s questions about the study; consent; screening; interviewer self-disclosure; and participant interview. The eligibility criteria for participation in the study were age eighteen or older, prior or current cancer, self-subscribed LTC that (I) either began or was substantially advanced in the context of cancer and (II) began more than 6 months before interview, a self-scored distress level on the day of the interview of less than 3 on a 0–10 visual analog scale (similar to the Distress Thermometer), and ability to take part in an audio-recorded interview. All nine candidates passed screening and were interviewed.

Demographics

Three of the nine cancer survivors were in cancer treatment at the time of interview: two in recurrence and one in a second course of treatment. The time since first diagnosis ranged from 3 to 29 years. Multiple primary cancers were reported by two of the participants. The age of four participants was in the range 46–65, four were 66 or older, and one participant was less than 46 years old. Among the eight women and one man were seven White, one Black, and one Asian. All participants had 4-year college degrees, and eight had post-graduate degrees. Four identified themselves as Jewish, three as Christian and the remainder were unaffiliated. Five participants were employed (only two were full time due to sequelae of cancer treatment) and four were retired. Five engaged in volunteer work.

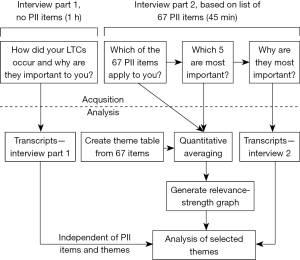

Interview structure

Immediately after finalizing informed consent and screening, a 2¼ hour private research session was conducted at the host institution (see Figure 2). An hour-long, semi-structured interview was used to elicit a detailed description of experiences related to the participant’s LTCs. Each semi-structured interview began with the same question: “When you heard about this study, what made you want to take part?” Following a 10-minute break, the participant was given a list of 67 PII items and asked to (I) mark the items that were part of their experience of cancer-related positive personal change; (II) report any important parts of their experience that were missing from the list (not reported in this article); (III) choose approximately five items from the same list as being the most important in their own experience of change; and (IV) explain why those five were important.

Analysis and interpretation of average scores for themes

The prevalence score for a single item in the PII list represents the percentage of participants who endorsed that item as part of their experience of positive personal change. The prevalence score of a theme represents the average of prevalence scores for all items in the theme. For example, if all nine participants marked three out of four items in a theme as part of their experience, the prevalence score for that theme would be 75% (27 out of 36 responses).

Participants were also asked to identify approximately five items from the same list of 67 items as being the most important in their own experience of positive change. The importance score for a single item represents the percentage of participants who identified that item as one of the 5 most important items. Importance scores are necessarily low percentages because participants were asked to name only 5 out of 67 items as “most important.” If an item has an importance score of 22%, it means 2 out of 9 participants identified that item as one of the 5 most important (22% is a relatively high score).

The importance score for a theme is the average of the importance scores of the items contained in the theme. Suppose a theme has four items, and the importance score is 0% for item 1, 11% for item 2, 0% for item 3, and 22% for item 4. The importance score for that theme would be approximately 8%.

Results

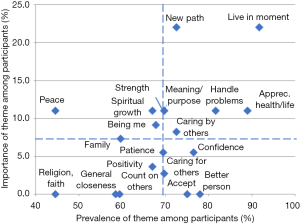

Mean scores for prevalence of experience and importance of experience were computed for each item theme (Table S1), enabling the responses to themes to be compared visually in a scatter plot (Figure 3). On average, 69% of the items were marked as part of all participants’ cancer-related experiences, indicating that the PII items were quite relevant to the experiences of our participants. This average is represented as a vertical dashed line from 69% on the “Frequency of Experience” axis. The average of all importance scores is calculated as the ratio (5 items allowed)/(67 items in the list). This average corresponds to 7.5% of the 67 items being marked as the five most important, and it is represented as a horizontal dashed line from 7.5% on the “Importance of Experience” axis.

Two themes stand out as most important to our participants. The importance of “new path” was not unexpected because it is natural for LTC to involve a new path in a cancer survivor’s life. However, we did not expect that when our participants scored all outcomes in terms of importance and occurrence, “LITM” would stand out among the many positive subjective outcomes. Our participants did not mention training or practicing mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) or other training that would develop LITM. We lacked a clear understanding of why LITM appeared to be significantly more important in the process of LTC than many of the other themes.

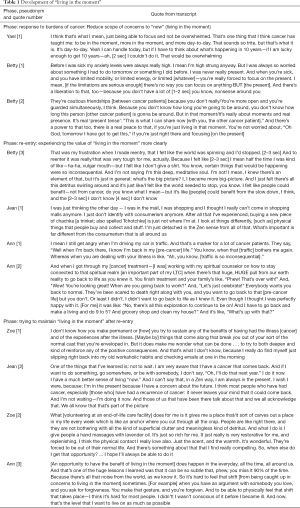

Having seen in Figure 3 that LITM stands out from the other themes, we looked back into transcripts to see what our participants had said in relation to LITM. The relevant excerpts are categorized in three groups in Table 1. The grouping of these quotes in Table 1 was created strictly based on patterns that emerged from our participants’ quotes and not based on any constructs, literature or another source.

Full table

The first group of quotes of Table 1 contains a common pattern. Each one speaks of a substantial challenge faced by the participant, and a certain tactic for reducing the challenge. One participant, with pseudonym Yael, has had a series of four primary cancers. At the time of the interview she was dealing with a metastasis. In Yael’s quote, she says the challenges that face her are overwhelming. Her coping ability is too limited compared to those challenges. An important part of her pragmatic and effective response is to narrow her attention to the challenges in the present—not in the future. Her description does not show evidence of seeking any positive affect (enjoy the moment, appreciate each day, etc.). She wants to be in the moment to avoid being overwhelmed.

Betty says that prior to cancer she wasn’t a person who was ever in the moment. She mentions that the limitations of energy and mobility she’s experienced during cancer treatment were severe enough at times that she couldn’t do anything but be in the moment. Like Yael, she seems to say that she was not seeking any positive affect. However, she did discover a benefit of narrowing her attention to the present, and avoiding having “a lot of nonsense” around her (a reference to dysfunctional relationships she described elsewhere in her interview).

In a second quote, Betty describes how living in the moment is an effective way of forming friendships in the context of another limitation: cancer patients’ uncertainty of lifespan. And as in her first quote, she discovers a benefit as though by accident, while very consciously using LITM to deal with a problem. The benefit is not just less worries (decreased negative experience), she describes it as an increased power and real peace (increased positive experience).

The second group of quotes also has a common theme. At times when participants were faced with a transition back into normal life, many participants experienced a strong contrast between LITM to limit their concerns (a tactic they used to cope with the challenges of cancer) and the wide-ranging, more trivial concerns of healthy people going about their normal lives. This contrast seemed to cause them to see the values of LITM more clearly. Those values were of two types: the reduction in the burden of concerns, and the unexpected benefits.

The third group of quotes describes participants’ efforts to maintain the benefits of LITM after re-entry into normal life (carrying the concerns of past, present, and future). These efforts ranged from doing enjoyable things now rather than at some future time (as in the proverb “making hay while the sun shines”) to putting oneself into a very out-of-the-ordinary role and environment for a couple of hours every weekend (volunteering to give massages in an end-of-life facility). Our participants described their strong desires to maintain experiences of LITM even though they acknowledged that it was difficult and that they’d had some failures.

Discussion

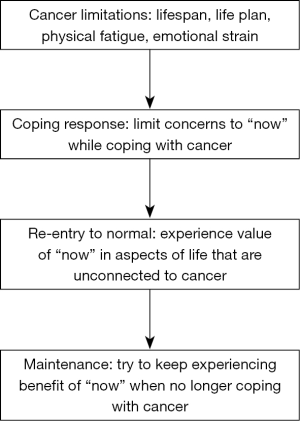

For the sake of discussion, we have organized LITM themes from Table 1 in a diagram (see Figure 3). Cancer can impose limitations and challenges on may domains of a patient’s life: a much more limited lifespan, widespread disruption of life plans, physical pain and fatigue, and emotional strains of many types. There are many coping strategies and tactics a patient may employ to manage these concerns. Depending on circumstances, patients may be expected to discover that some coping methods work better for them than others.

Our participants were faced with the adversities of cancer, and in that circumstance, they experienced a change in themselves that was so positive that they refer to it as life-transforming. One coping tactic they seemed to share is LITM—a moment-by-moment experience of reducing the burden of the worries associated with cancer by dealing only with what is happening right now. As they applied this transient experiential tactic, they also noticed that LITM brought unexpected benefits and even experiences of positive affect. They continued to notice the benefits when they were faced with transitioning back into “normal life” with its relatively wide range of concerns—many of those concerns appearing to be ill-considered, unfounded, or unwise. As though viewing from outside of “normal life,” participants seemed to feel that the joys of life were being overwhelmed by carrying too many concerns. They sometimes found it difficult to articulate this contrast (see Betty’s third quote). This contrast appeared to be based on a change in mental function that our language does not yet readily describe. Even though it was a challenge to articulate, the value of LITM was very clear to them, and they sought ways to maintain access to the transient experience of LITM (see Ann’s third quote). They found that maintaining access to LITM while living “normal life” was often a losing battle, yet they recognized that it had been important in the process of LTC and the desire for more LITM remained. Even participants whose cancer treatment was completed more than 10 years before their interview ranked LITM items as highly important.

Many studies of the psychosocial dimensions of cancer have used the posttraumatic growth inventory (PTGI). The PTGI is based on a theory that trauma is the dominant causal factor for the personal growth experienced by cancer survivors. However, there is more than one theory of how growth occurs among cancer survivors and we did not want to bias our study with pre-selection of a growth theory. This was one of the reasons we chose to use the PROMIS item bank, which has items associated with a variety of personal growth theories. Our grounded theory approach (including use of the PROMIS item bank) enables us to not only avoid such assumptions, but also identify which existing theories are better supported by our data.

In terms of patient experience during cancer treatment, recovery and re-entry to normal life, our sample of cancer survivors responded very strongly to the four LITM items supplied to us by the PROMIS PII team. After our data collection and analysis, the PROMIS PII team released the final 39 calibrated positive items for the PII assessment tool. Very unfortunately, three out of the four items in our highest-scoring theme “LITM” were no longer included in the PII item pool. The removed items were “My illness has taught me to enjoy the moment more” (frequency score 100%, importance score 22%), “My illness has helped me learn to live for today” (frequency score 89%, importance score 33%), and “My illness has helped me be less easily bothered by little things” (frequency score 89%, importance score 33%). Only the item “My illness has helped me appreciate each day more fully” (frequency score 89%, importance score 0%) remained. We feel this indicates a strong need for an improved item selection system by the PROMIS team.

Assessment items may be developed in relation to each phase of LITM illustrated in Figure 4. For example, some possible items corresponding to the coping response phase are “Focusing on the present helped me avoid having too many concerns,” or “I learned to focus on the present when there were too many worries,” or “I learned to focus on the present whenever it became difficult to deal with my illness,” or “Having an uncertain future makes me focus my relationships on the present.” Additionally, it may be important to develop items that capture some of the struggles of re-entry to a new normal life: “It’s been tough for me to re-enter normal life,” or “I just don’t identify with consumerism anymore,” or “In some important ways, I don’t want to go back to my life before cancer.” Finally, items could be developed to capture the difficulties of maintaining LITM in normal life: “After my illness, I slipped right back into my old habits,” or “I make an effort to be present in everyday activities,” or “I feel a kind of inner shift when I am able to intentionally live in the moment.”

The identification of a theory of LITM is important, because caregiver advice and/or intervention is generally based on knowledge of the relevant causal factors. It was surprising to us that our participants did not identify trauma, or reflection on traumatic experience, as motivating their focus on living in the present moment (LITM). The data in Table 1 indicate that our participants found the challenges of living with cancer and treatment sequelae to be much greater than the challenges of normal life, as anticipated. However, they further indicated that it was their limited capacity for coping with these increased challenges that caused them to focus on LITM. This does not appear to be a response to trauma; our evidence indicates LITM is a pragmatic response that can readily contribute to LTC. Therefore, Hobfoll’s model of conservation of resources, including action-focused growth, seems a much better fit to our data than Tedeschi’s PTG model. The motivation for LITM among cancer survivors who also self-report LTC seems to be conservation of their own personal resources for coping with increased stresses. LITM in this study’s population is a reminder that correlation of cancer survivors’ traumatic or distressing experiences with LITM does not mean causation, and that the application of grounded theory research designs (including use of the PROMIS PII item bank, which represents a variety of personal growth theories) can help distinguish causation from correlation. Other populations may have different motivations for LITM. In general, we agree with Westphal and Bonanno’s opinion that there are limitations in the current theories of growth and resilience. These limitations require deeper consideration to achieve satisfactory understanding of phenomena such as LITM that are highly valued by cancer survivors.

Strengths and weaknesses

Each participant recruited at the non-profit holistic support center became involved in that center because they very actively sought support for themselves as cancer survivors. Also, our sample was largely composed of highly educated, highly articulate, white women who are cancer survivors. There is an obvious need to extend this research to a much more diverse sample.

The use of self-reported positive subjective LTC as an eligibility criterion for participants was extremely important, and greatly increased the strength of our evidence. We suggest that future development of PII assessment items should include testing of items on persons self-reported positive subjective LTC. Without this step, the most important positive outcomes may not be fully captured by the assessment items.

In hindsight we realized that the average importance score may not always be balanced. Due to the method of selection that was reported by some participants during interviews, themes with two or more highly similar items could tend to have lower average importance scores. For example, some participants reported not selecting the item containing “see how strong I can be” and “become a stronger person” as among their five most important items because they’d already selected the item containing “stronger than I thought.”

As some participants discussed why they chose certain items as the five most important, they indicated that they avoided picking other items that appeared to have the same meaning as one they’d already selected as among the five most important. In terms of individual items, this means they may have tended to select items toward the beginning of the list instead of those toward the end of the list. In terms of themes, this might further reduce the importance scores of themes that may be highly important to participants.

However, we note that the three items with the highest importance scores (33%) have item numbers 45, 51 and 64—they were all toward the end of the list, perhaps because these are the items they’d seen most recently. There were eight items with an importance score of 22%, and they have item numbers 2, 3, 5, 10, 24, 36, 56 and 67. This may reflect some tendency to pick the items with an importance score of 22% from the beginning of the list, but not an overwhelming tendency.

Conclusions

Supportive care services in hospitals strive to facilitate positive psychosocial outcomes for their patients. Positive psychosocial outcomes are especially valued during the course of serious chronic illness, life-threatening disease, and terminal phases of illness. As the science and technology for facilitating those outcomes advances, assessment instruments are needed that can fully capture highly positive outcomes. We have surveyed patients who have self-reported positive subjective LTC in the context of cancer to determine their ranking of 20 themes of positive outcomes, using items supplied by the PROMIS PII item development team. Our participants ranked “LITM” as higher in combined importance and frequency than the other 19 themes we surveyed. Through interview transcripts of their experiences of positive change, we have found evidence that LITM was a highly effective coping tactic during cancer treatment for our participants. The motivation for adopting LITM appears to be conservation of resources (conserve mental capacity available for coping, consistent with Hobfoll’s model of conservation of resources), and this tactic was also accompanied by unexpected positive experiences of greater enjoyment of life. We suggest that a small set of assessment items in the PROMIS PII instrument (and other quality of life instruments) should be designed to capture the different phases of LITM: as a coping tactic to manage overwhelming concerns, as a means to enable enjoyment and appreciation of life in the midst of the challenges of illness, and as an aid for cancer survivors when re-structuring their day-to-day life to achieve greater quality of life.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to the PII item bank development team and the NIH PROMIS organization for providing us with a suitable list of psychosocial questionnaire items prior to item calibration, final item selection and item bank release. Funding was provided by NIH IRTA annual grants (Intramural Research Training Award) to the first author.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The protocol for the research project was approved by the NIH IRB (protocol number 09-CC-0227), and it conforms to the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration (revised 2013).

References

- Andrykowski MA, Lykins E, Floyd A. Psychological health in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs 2008;24:193-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mount BM, Boston PH, Cohen SR. Healing Connections: On Moving from Suffering to a Sense of Well-Being. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:372-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saunders C. The evolution of palliative care. Patient Educ Couns 2000;41:7-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Denz-Penhey H, Murdoch C. Personal resiliency: serious diagnosis and prognosis with unexpected quality outcomes. Qual Health Res 2008;18:391-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mount B. Healing, quality of life, and the need for a paradigm shift in health care. J Palliat Care 2013;29:45-8. [PubMed]

- Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1207-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am Psychol 2000;55:647-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Folkman S. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety Stress Coping 2008;21:3-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heintzelman SJ, King LA. Life is pretty meaningful. Am Psychol 2014;69:561-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]