The influence of relationships on the meaning making process: patients’ perspectives

Introduction

The search for the meaning of health, illness, and self after diagnosis and during treatment of a chronic or life limiting disease is an ongoing process. Previous research has shown that adjusting to this type of life situation may require individuals to modify their life goals and expectations, given that serious illness often interferes with goals and long-term plans in life (1). Further, existential concerns triggered by the onset and progression of disease may lead to the need to make sense of illness or give it meaning (2). Scholars continue to examine the subjective variable of meaning making in illness as a method to understand the patient and also provide valuable information to the medical community that may increase person focused/patient centered care as opposed to disease focused care (3-5).

Although meaning making as a response to the diagnosis of a threatening life event is not well understood, scholars considered it to be a measurable concept and urge continued work to seek better understanding (3,6-8). Meaning was established as being an important part of the outcome and process of negotiating traumatic life events (9) and thought to be significant in the process of positive adjustment in chronic illness and healing through restructuring or re-evaluating the situation (2,10-12).

Recent evidence indicates that those who find meaning in life may be better able to adjust to medical challenges including improvement in quality of life. Total quality of life was related to the meaning ascribed to illness among patients diagnosed with stage I and stage II lung cancer (13). Meaning of illness, social support, and coping were measured in a sample of 85 patients and 85 family members. The Meaning of Illness Questionnaire (14), which included subscales of impact, meaning/expectation, managing, and burden was used. The patients’ who reported the ability to manage their illness had the highest quality of life scores, and those who ascribed positive or optimistic meaning to their illness reported a greater ability to live with the illness. Similarly, cancer patients with higher meaning in life reported improved quality of-life (15). Even in traumatic situations, meaning was associated with higher psychological well-being in a sample of individuals living with spinal cord injury (16).

Theoretically, Frankl (17) proposed that finding meaning is a part of human nature and is central to pursuing a life characterized as purposeful and goal-oriented. Bandura [1986] expounded on Frankl’s thought and proposed that all human behavior is driven by meaning and goals, and that these goals are central to a person’s ability to create meaning in stressful life events such as a diagnosis of life threatening illness (8). Frankl’s proposition was later described as global meaning, which gives direction for one’s life (18). Global meaning encompasses connections that give people meaning, and their beliefs and expectations for the future (8,19), as well as subjective emotions (20). Adding to the foundation set by these scholars, Berlin (21) suggested that meaning is created from external sources of information. It is in the process of internalizing this information that the structures of personal values, norms, and roles are created. The wide variety of external sources one is exposed to during this process results in an individual’s sociocultural foundation.

Leary and Tangney (22) further framed this outcome as global beliefs. These global beliefs develop into views about the self and justice. It is these views that influence the core schemas that people use to evaluate life events (23). It is when unfavorable life events take place, such as the diagnosis of a life limiting illness, a person uses core schemas to appraise the situation. An incongruence between the event and core schema (global beliefs) can lead to loss of homeostasis and cause distress. During this time, a person struggles to regain stability and alleviate the distress to gain understanding and direction by forming new meaning. As a part of the meaning making process, when one’s core beliefs are being challenged, the current event and their prior life experiences are evaluated with intense focusing on purpose (24). This new meaning, developed as a result of the life event, is referred to as situational meaning (8,24,25), which is in turn used to adjust and make the current situation bearable. This ascribed meaning influences the perception, either positive or negative, of the disease (13). The new meaning may result in the desired stability and alleviation of distress or it can exacerbate the sense of instability and distress if the discrepancy experienced is not resolved (25-28). Sherman et al. (29) reported that when global meaning increases, distress decreases thereby supporting an improvement in quality of life. In their study, participants diagnosed with a life-threatening illness who reported higher global meaning also reported lower distress and improved health related quality of life. These multiple examples of the effects of meaning making during illness are thought to possibly influence the healing process.

Skeath and colleagues (30) completed a study exploring the attainability of healing in patients diagnosed with a life limiting illness who also had an aggressive disease trajectory and poor prognosis. The study was a qualitative approach to determine the process of healing. The findings described subjective healing in palliative care as a reduction in psychosocial or spiritual suffering until the patient decides they have reached a place of healing.

The purpose of the current qualitative study was to expand our understanding of meaning making for an individual diagnosed with a chronic or life limiting illness. Also, to explore the connection, if any, of how meaning making may lead to an outcome of psychosocial spiritual healing or exacerbate distress.

Methods

The goal of this secondary data analysis was to examine the influences of meaning making to determine its impact on a patient’s sense of healing.

Design

The current study utilized data collected during in-person interviews using a convenience sample of 30 palliative care patients. The original study was conducted at three different locations: the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center (NIH), a large research institution in Bethesda, Maryland; Johns Hopkins Suburban Hospital, a community hospital in Bethesda, Maryland; and Mobile Medical Care (Mobile Med), a community clinic located in Rockville, Maryland. The Institutional Review Boards and appropriate research governing bodies approved the protocol. The purpose of the original study was to conduct cognitive interviews, using semi-structured questions, aimed at establishing conceptual definitions such as the construct of healing. Willis (31) identifies semi-structured interviews as an accepted approach for conducting cognitive interviews.

The interviews took place during a 5-month period between February and June 2016. Eligible participants spoke English, were above the age of 18, and seen by a palliative care provider at one of the three sites. Exclusion criteria included patients with known brain metastases because of their poor prognosis and because they often develop progressive neurologic dysfunction that would confound the evaluation of the assessment questions. Interview question prompts were guided by items from the Healing Experience in All Life Stressors (HEALS) instrument (32). The HEALS is a 54-item self-administered scale that measures psycho social spiritual healing.

The interviews asked participants about their understanding of the items on the HEALS and the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with such statements. The response set was a 5 point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Participants were encouraged to elaborate on their understanding and explain specifically how the statement related to his/her life. The responses to the elaboration question are the subject of this paper.

Sample

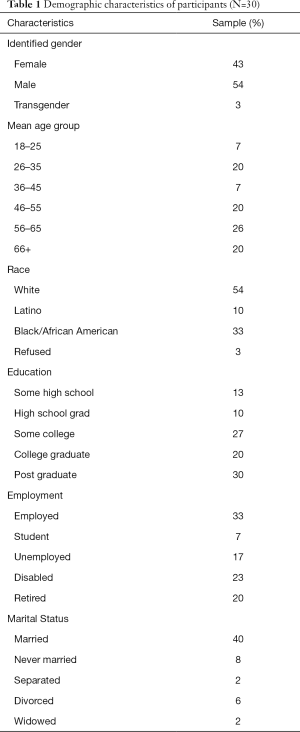

A total of 56 potential participants were approached based on convenience sampling with 30 participants enrolled (54%). A description of the study group can be found in Table 1. Most interviews were conducted at the NIH (80%). Participants self-classified race/ethnicity, with Caucasians making up majority of the sample. Gender was slightly less than equal with males exceeding females by 11%. Seventy-seven percent of the sample had some form of college education up to and including post graduate degrees. Given the presence of a life limiting diagnosis, 60% of participants did not work. The largest age groups of participants were split between ages 26–35 (20%), 46–55 (20%), and 56–65 (26%) with 47% self-reporting as married.

Full table

Procedures

Screening for eligibility was based on medical record search and palliative care clinician referrals. After introducing the study in detail, written informed consent inclusive of consent for audio recording was obtained at each site. The demographics form was given to the participant for completion. The participant was then informed when the audio recorder was started. Trained members of the research team conducted the interviews in private inpatient or outpatient rooms. The session involved a semi structured interview oriented toward eliciting the sequence of experiences and decisions that led to the selected answer on the HEALS. All interviews occurred in-person and took between 30–90 minutes to complete with one interview lasting 120 minutes.

Data analysis plan

This qualitative study was guided by a grounded theory approach to the analysis of the original data. The analysis was a line by line process for coding allowing for the simplification of the data from patient narratives and served as a means to organize it into to meaningful categories, leading to theme development (33).

Results

The overall theme that emerged indicated a strong emphasis on meaning making through relationships—connecting with family and friends, and finding more compassion for others. For instance, some responders indicate that family relationships were more meaningful especially after diagnosis, and specifically with their children. One participant implied that she has always had a meaningful relationship and went on to say “… I think that what happened is, is that um, w-w-we’ve always had uh, meaningful relations, but…, given the circumstances, I mean, we had a moment the other day when my son started talking about how important it [our relationship] was to him.” She went on to say “… it’s not as though I need to hear this to believe it—but sometimes you do have to say it.”

In the same vein, thoughts about dying brought more meaning to life, the patient referred to kids and grandchildren growing up, “I wanna see a life with my kids. So, yeah it’s a very big meaning in my life right now. Specially, I just became grandpa too.” Another participant stated she was “aware of who I am and of relationships with family.” Another respondent, when asked about being present responded, “both physically and mentally…being there with … children and focusing attention on them.”

As a result of diagnosis/illness, two of the respondents found new meaning through family relationships, which suggests some level of adjustment by finding this new meaning and developing situational meaning. The later of the quotes encompasses Frankl’s (17) definition of meaning, being inclusive of purpose and goal orientation as indicated by the respondent’s desire to spend time with kids and also referring to a new grandchild, bringing about a sense of fulfillment. Newly discovered sense of purpose has been found to support positive adjustment and leading to a reduction in the symptoms of distress during life threatening illness (34-36).

In addition to the connections with family, one respondent spoke of the importance of friendships in terms of meaning, the relationship became “more connected.” Overall, respondents did not necessarily ask for support from friends, one participant did not seek meaning but experienced the development through “mental and physical presence” and through “interaction with more content, more sharing information, and more conversation.” The interaction and sharing of information has the potential to influence the reduction in of distress as the psychosocial adjustment to illness is often time very distressful (37).

When asked about changes in compassion for others, two participants shared that “I understand more and I can see situations better” and “I’ve tried hard to understand other people’s point of view.” Another patient, when asked about deepening relationships, stated that it “took a toll for the good… with a past relationship.”

Discussion

The data collected in this study suggest the development of meaning is gained through relationships, specifically an increase of meaning in family relationships, the connection to friends, and a change in compassion towards others. A common societal misperception of meaning making is that it is a personal, individual journey. The Presence of Meaning theory proposes that meaning is generated when individuals view their lives as significant and purposeful (6). This suggests that it is based on relationships with others rather than an individual pursuit. The participants in this study reported finding significance and purpose, when life limiting illnesses strengthens their relationships and they have what they felt as a valued place in that world. A possible explanation for this phenomenon could be the process of self-reintegration that takes place in the presence of a terminal illness (36). As a part of the self-reintegration, patients find it necessary to re-evaluate relationships, even in the absence of an end of life situation. During this examination, the realization of mortality prevails and relationships become important. This awareness brings about a sense of urgency to be a part of relationships, and reawaken in others the longing to create meaning. This type of information is valuable to health care providers as a segue to discuss the inclusion of family members as support when establishing the goals of care.

Healthcare providers see patients during life-altering moments when they are diagnosed and treated for serious illnesses. While the immediate concerns often center on day-to-day medical interventions, the act of healing extends beyond addressing the physical malady—because the impact of illnesses reverberates the core of an individual, or their global meaning. What is a singer to do if she loses her voice from the cancer and subsequent treatment? What about a husband and father who is the sole provider for his family and can no longer work because of illness? When patients’ core identities are challenged through life-threatening illnesses, treating the disease is a crucial first step, but intentionally providing space for conversations on the impact of illness and meaning making can facilitate the process of healing. The presence of a caregiver, family, and friends seem to allow patients to maintain purpose and have meaning, supporting the ability to cope with the life altering situation.

Little research exists to substantiate relationships as a conduit to develop meaning in the process of psychosocial spiritual healing. However, Kaptchuk and Eisenberg (38) propose that a vital component of healing is connectivity, which often manifests as compassion, adding value to the importance of relationships. Other literature speaks of healing relationships that foster a sense of belonging and safety giving patients a sense of empowerment (39).

This research helps provide preliminary evidence of what mechanisms are involved in the healing process (i.e., the focusing on relationships). Though, not all responses mentioned value changes in relationships post diagnosis, one participant stated there was “an appreciation for others’ lives” after diagnosis; while another spoke of an effort to “keep the relationships going”.

Of interest is that in the quantitative portion of this study most agreed that relationships with others is an important aspect of developing meaning after diagnosis of a life limiting illness. Specifically, 80% of participants agreed that relationships with others had deepened since diagnosis, 81% agreed that relationships with friends were more meaningful, and 86% felt that family relationships had become more meaningful.

Conclusions

Future investigations could explore relationships as a variable in finding meaning during life limiting illness, particularly among patients and their loved-ones or among patients and their physicians. Upon further validation, the HEALS assessment could serve as a diagnostic tool to identify the strengths of patient relationships, which will be helpful for health care professionals as they attempt to provide holistic, patient-centered care.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the patients and staff at the NIH Clinical, The Johns Hopkins Medicine Suburban Hospital and the Mobile Medical Center Inc. for supporting the efforts of this project. The Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Clinical Center supported this research.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- Pinquart M, Silbereisen RK, Frohlich C. Life goals and purpose in life in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:253-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang W, Staps T, Hijmans E. Existential crisis and the awareness of dying: the role of meaning and spirituality. Omega (Westport) 2010;61:53-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thorne SE. The science of meaning in chronic illness. Int J Nurs Stud 1999;36:397-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell GJ, Closson T, Coulis N, et al. Practice applications. Patient-focused care and human becoming thought: connecting the right stuff. Nurs Sci Q 2000;13:216-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin RS, Richardson ND. Patient-focused care: using the right tools. Chest 2006;130:73S-82S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, et al. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life. J Couns Psychol 2006;53:80-93. [Crossref]

- Morgan J, Farsides T. Measuring Meaning in Life. Journal of Happiness Studies 2009;10:197-214. [Crossref]

- Park CL, Folkman S. Meaning in the Context of Stress and Coping. Rev Gen Psychol 1997;1:115-44. [Crossref]

- McIntosh DN, Silver RC, Wortman CB. Religion's role in adjustment to a negative life event: Coping with the loss of a child. J Pers Soc Psychol 1993;65:812-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barkwell DP. Ascribed meaning: A critical factor in coping and pain attenuation in patients with cancer-related pain. J Palliat Care 1991;7:5-14. [PubMed]

- Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 2002;24:49-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sherman AC, Simonton S. Effects of personal meaning among patients in primary and specialized care: Associations with psychosocial and physical outcomes. Psychol Health 2012;27:475-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fife BL. The role of constructed meaning in adaptation to the onset of life-threatening illness. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:2132-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Downe-Wamboldt B, Butler L, Coulter L. The Relationship between Meaning of Illness, Social Support, Coping Strategies, and Quality of Life for Lung Cancer Patients and Their Family Members. Cancer Nurs 2006;29:111-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weir R, Browne G, Roberts J, et al. The Meaning of Illness Questionnaire: further evidence for its reliability and validity. Pain 1994;58:377-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DeRoon-Cassini TA, de St Aubin E, Valvano AK, et al. Meaning-making appraisals relevant to adjustment for veterans with spinal cord injury. Psychol Serv 2013;10:186-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frankl V. Mans Search for meaning: An introduction to Logo Therapy. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Washington Square Press, 1963.

- Lazurus RS, Folkman S. Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing, 1894.

- Paragament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York, NY: Guilford, 1997.

- Dittmann-Kohli F, Westerhof GJ. The personal meaning system in a life span perspective. In: Recker GT, Chamberlain K. editors. Exploring Extistential meaning: Optimizing human development across the lifespan. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000:107-23.

- Berlin S. Clinical social practive: A cognitive-integratie prospective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Leary M, Tangney J. Handbookk of self and Identity. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. The self as an organizing construct in the behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2003:3-14.

- Mischel W, Morf C. The self as a psychosocial dynamic processing system: a meta-psychological perspective. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP. editors. Handbook of Self and Identity. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2003:15.

- Frankl VE. The meaning of suffering. In: Meier L. editor. Jewish Values in Bioethics. New York, NY: Human Sciences Press, 1986:117-23.

- Skaggs BG, Barron CR. Searching for meaning in negative events: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2006;53:559-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joseph S, Linley PA. Positive Adjustment to Threatening Events: An Organismic Valuing Theory of Growth Through Adversity. Rev Gen Psychol 2005;9:262-80. [Crossref]

- Park CL, Edmondson D, Fenster JR, et al. Meaning making and psychological adjustment following cancer: The mediating roles of growth, life meaning, and restored just-world beliefs. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:863-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol Bull 2010;136:257-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sherman AC, Simonton S, Latif U, et al. Effects of global meaning and illness-specific meaning on health outcomes among breast cancer patients. J Behav Med 2010;33:364-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skeath P, Norris S, Katheria V, et al. The Nature of Life-Transforming Changes Among Cancer Survivors. Qual Health Res 2013;23:1155-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Willis G. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc, 2005.

- Sloan DH. An assessment of meaning in life-threatening illness: development of the Healing Experience in All Life Stressors (HEALS). Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2017;8:15-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication, 2014.

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Social Patterns of Distress. Annu Rev Sociol 1986;12:23-45. [Crossref]

- Holder GN, Young WC, Nadarajah SR, et al. Psychosocial experiences in the context of life-threatening illness: the cardiac rehabilitation patient. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:749-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldrop DP, Meeker MA. Final decisions: How hospice enrollment prompts meaningful choices about life closure. Palliat Support Care 2014;12:211-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steger MF, Kashdan TB, Sullivan BA, et al. Understanding the Search for Meaning in Life: Personality, Cognitive Style, and the Dynamic Between Seeking and Experiencing Meaning. J Pers 2008;76:199-228. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM. Varieties of Healing. 1: Medical Pluralism in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:189-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moerman DE, Jonas WB. Deconstructing the Placebo Effect and Finding the Meaning Response. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:471-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]