Sacred space and the healing journey

Introduction—sacred space and the healing journey

Aesthetics: the word’s origin is derived from the Greek aisthetikos, which means sensitive and perceptive. From the root word aisthanesthai, or “to perceive (by the senses of the mind)” (1), modern aesthetics is essentially the study of human feeling.

Medical facility healing environments are the manifestation of aesthetics—they are the physical form of human feeling. And palliative care patients’ feelings, state of mind and spirit profoundly affect their body and course of getting well. By engaging patient’s in spirituality, culture and community before and after a medical appointment, medical providers can more quickly and positively affect their therapy’s outcome.

Sacred healing spaces were the primary healing environments for societies of the ancient world, curing individual and collective maladies. In the 5th Century BCE, for example, the Archaic Greeks created a healing city at Epidaurus (Greece). This healing city incorporated both the Asclepion (spiritual) and Hippocratic (scientific) healing modalities. Likewise in Japan, tea rituals were often used to mend society during the brutal civil wars of the Kamakura Period [1185–1392]. Samurai warriors traumatized by loss particularly benefitted from tea rituals conducted within gardens (Figure 1). One important ancient and current objective of these rituals is to become whole again: the instant a practitioner enters the tearoom to prepare koicha (thick tea), he or she confronts a unique opportunity to achieve that “condition of original wholeness, health, or holiness” that is the objective of all religious behavior (2).

By conducting healing rituals in rarefied architectural environments, individuals with ailments could transcend, become whole, be reborn and commune with god(s). This ancient sacred architecture is conveyed through allegory, metaphor and symbols. But all architecture is a biography of cultural beliefs, cultural values, and collective aspirations.

In the modern era of technology and specialization, it is easy to see why hospital facilities are rigidly segregated into medical departments. This type of master planning makes meaningful multi-disciplinary collaborations difficult. Segregation in today’s medical environment is articulated in the article, “Organizational Transformation: A Model for Joint Optimization of Culture Change and Evidence – Based Design”: hospitals traditionally have had organizational structures that make it difficult for staff to act collaboratively as a team. Kimball [2005] described hospital structures a “paternalistic, fragmented, independent silos, top-down, top heavy, bureaucratic, multiple layers, hierarchical, like a state bureaucracy, lack of two-way communication, physician centric, clinical model driven by business model” (3).

Today’s hospital’s sacred places are often regulated to utilitarian spiritual spaces and passive “healing gardens”, which are often isolated from inpatient and outpatient units. These “healing gardens” are a lunch break space, and not utilized as the therapeutic healing modality that they should be.

This article will provide medical providers, researchers and administrators a brief history of healing environments in the western world, and illuminate how spiritual and communal architectural components allow for ritual, meditation and spiritual performance can be integrated with inpatient and outpatient clinics to create opportunities for complimentary and alternative healing modalities (CAM) collaborations and patient choice. I will begin by briefly describing: the three human institutions that comprise society; the master plan of the 5th Century BCE Greek healing city of Epidaurus; and the labyrinth as an architectural component within three contemporary healing environments located in Chicago (unbuilt), San Vito d’Altivole, Italy and Cedar Rapids, Iowa. The final segment illustrates how spiritual components contribute to the healing quality of space that is incorporated into the Department of Veteran Affairs Healing Environment Design Guideline (VAHEDG).

Three human institutions comprising and sustaining society

It is not possible for an individual to heal in isolation. Patients can only heal with the support of loved ones, friends, and community. But what comprises community?

Giambattista Vico was the 18th century author of New Science (Scienza Nuova), a book that interprets the ancient myth of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, not as fantastical stories, but as historical events. Vico deconstructs Homer’s poetry for psychological archetypes, the origins of society and the human institutions necessary for civic discourse. He identified three such institutions essential for the founding and sustenance of a society:

- Divine providence—belief in god;

- Solemn matrimony—the importance of family and procreation and sacred nuptials;

- Burial—the universal belief in the immortality of the soul and importance of personal and collective memory.

Spirituality is a common thread in all Vico’s three human institutions. These sacred institutions were manifested in Italian architecture and integrated into the urban and community fabric. The center of the city contained a piazza composed of sacred, civic, residential and commercial space. The piazza provided a venue for incidental meetings, community events, commerce and religious festivals. But it was the basilica that stood as the place of moral authority, worship, nuptials and burial rites in Italian society. While adjacent to the profane world, the basilica possessed a boundary defining its domain: what has been said will make it clear why the church shares in an entirely different space from the buildings that surround it. Within the sacred precincts the profane world is transcended. On the most archaic levels of culture this possibility of transcendence is expressed by various images of an opening; here, in the sacred enclosure, communication with the gods is made possible; hence there must be a door to the world above, by which the gods can descend to earth and man can symbolically ascend to heaven. We shall soon see that this was the case in many religions; properly speaking, the temple constitutes an opening in the upward direction and ensures communication with the world of the gods (4) (Figure 2).

Epidaurus an international Greek healing city 5th century BCE

In recent years, contemporary medical center design has rapidly evolved into a user-centered environment for both patients and their families. Medical centers have upgraded their interior and exterior aesthetics to be more visually pleasing and provide a less stressful patient experience. Integrative departments have been rapidly forming across the medical center landscape. But integrated healing environments working in unison with CAM have not. These medical facilities could take a cue from the ancient, international healing city of Epidaurus, located about 50 km northwest of modern Athens and settled in the late Bronze Age.

About 2,500 years ago, the Greeks had been engaged in continuous warfare for centuries, which profoundly affected a society’s collective health as well as an individual’s well-being period. The Greek Society needed a space like Epidaurus.

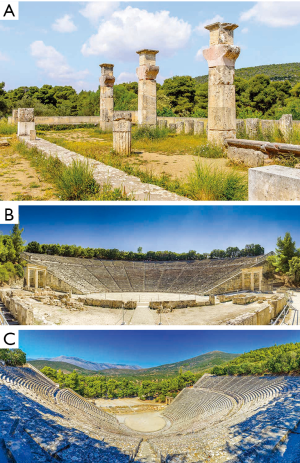

The city evolved into a sanctuary site dedicated to heroes and the gods. The healing cult of Asklepios became the primary god of worship early in the 5th Century BCE. While primary healing activity took place in the Asklepian (temple), the entire city of Epidaurus was utilized as a healing environment, integrating sacred space, profane space and healing rituals. The ancient city’s location also realized two important, evidence-based principles of modern healthcare design: views of nature and the incorporation of sunlight.

The selection of Epidaurus’ building site was a critical design concern: the ancient Greeks knew how to select for the residences of their gods the most suitable locations in their country. The enchantment the pleasant Plain of Epidaurus proffers the visitor even today was probably one of the reasons why the sanctuary was established there. The climate is mild. The tranquil greenery would, even then, have furnished the sick pilgrims with relaxation and serenity. The sanctuary was also called the Sacred Grove. The plenteous spring waters were another influential factor (5).

A pilgrim approaching Epidaurus would view the propylaea (gate), which was a sacred domain marked by posts or boundary stones. The differentiation between the profane world and the sacred was essential for a pilgrim to transcend the present (illness) and begin to envision the future (cure). Pilgrims who entered the sacred domain of Epidaurus encountered an inscription carved in stone: “Pure must be he who enters the fragrant temple; Purity means to think nothing but holy thoughts” (6).

Inside the sacred domain were basins for washing and purification. Rituals and accompanying sacrifices would lengthen the purification process. These purification rituals were important acts that released stress brought to the sacred domain from the outer world. In addition, it would bond family members to the patient and focusing the energies of the individual on the process of healing. After purification, the pilgrim would experience a series of sacred environments, which created a healing aesthetic that integrated with sacred healing rituals: the priests who directed the believers must have created a state of intense auto-suggestion and religious exaltation in them so that the god would appear in their sleep and they would receive his miracle. The compunction was further emphasized by hymns chanted by special singers, the Paianists.

After the testing of the soul the moment of “Enkoimesis” arrived. The priests led the invalid to the Abato (or Adyto or Enkoimeterion). This was the building in which he would spend the night of great expectation. Within its hallowed halls, illuminated initially with subdued mysterious light emitted by the sacred oil-lamps, overcome with religious desire, with an inflamed imagination and anxiety over the outcome, the invalid surrendered his body to sleep. The priest withdrew, leaving the halls in darkness. The god appeared in a dream and performed the miracle. The next morning the sick person awoke cured (5).

The architectural environment described supports a menu of active and passive healing activities that range from solitary prayer to the viewing of Community Theater. While the Asklepian was the center of healing activity, Epidaurus’ other support spaces provided essential healing dimensions that allowed the pilgrim to customize their healing journey:

- Baths: for purification, relaxation and hygiene purposes;

- The Abaton: place for incubation (dream healing) an integral element for transcending the state of illness after the rituals in the Asklepian (Figure 3A);

- Theater: seating capacity for 14,000, communal catharsis dealing with continuous warfare and individuals overcoming adversity (Figure 3B,C);

- Stadium: viewing athletic events and watching athletes overcome adversity, communal bonding;

- Gymnasium: physical exercise;

- Monuments: testimonials for pilgrim’s cures, and worshipping the gods and goddesses;

- Banqueting hall: communal meals, bathing, and exercise.

The communal meal was essential to the Asklepian healing ritual. It allowed for small groups to bond, trust and share empathy in their common cause of healing. From the book Epidauros by R. A. Tomlinson: “A formal banquet was included in the ritual, and in the developed sanctuary there was a building which served as a Banqueting Hall for select worshipers, containing several rooms of varying size arranged round a large central courtyard. It has a magnificent entrance Propylon, complete with a ramped approach which shows that the worshippers entered in solemn procession” (7).

Within the ruins of Epidaurus, archaeologists have discovered 70 patient testimonials engraved in stone. These testimonials range from the desire to have a baby, heal war wounds, be rid of parasites and to alleviate headaches. The healing experience of Epidaurus is difficult to synthesize because it ended nearly 1,700 years ago. But Edward Tick, PhD, a clinical psychologist, brings his patients to an Epidaurus-like state in contemporary therapy: “The altered state of consciousness engendered by Asklepian purification and preparation rituals changes our body chemistry, disrupts our sense of time and space, and shifts our understanding of who we are and how the universe is organized. This shift allows us to approach the divine powers open, undefended, and vulnerable. In other words, purifications entails surrendering our usual ego boundaries. During the ritual, these boundaries will be realigned into a new pattern that better serves our overall health and functioning” (8).

The multitude of sacred spaces and ritual opportunities available at Epidaurus contributed to the ancient city’s reputation as a place for healing among traumatized pilgrims.

The sacred labyrinth

Labyrinth is a useful and profound metaphor for sacred space and patients’ healing journeys. In the book Through the Labyrinth, author Herman Kern identifies three forms as a labyrinth concept:

- Labyrinth as a literary motif (usually a maze);

- Labyrinth as a pattern of movement (a dance);

- Labyrinth as a graphic figure (a drawing) (9).

The labyrinth is the powerful symbol of an individual or society seeking rebirth, enlightenment and transcendence. It is an allegory that artists, authors and architects often use to manifest “rites of passage”. It is a “narrative of experiences” possessing a beginning, middle and end. You enter the labyrinth in one state of being, arrive at the symbolic center of enlightenment and exit in a “different state of being”—with a question answered, different perspective, change in belief or a change in life’s course.

The Brion Tomb, San Vito d'Altivole, Italy

Sacred space has been utilized as a healing tool since the inception of human societies. The first human construct was not a dwelling or fortification, but a burial mound utilized to begin individual and collective healing, says historian Lewis Mumford: “Early man’s respect for the dead, itself an expression of fascination with his powerful images of daylight fantasy and nightly dream, perhaps had an even greater role than more practical needs in causing him to seek a fixed meeting place and eventually a continuous settlement. Mid the uneasy wanderings of paleolithic man, the dead were the first to have a permanent dwelling: a cavern, a mound marked by a cairn, a collective barrow. These were the landmarks to which the living probably returned at intervals, to commune with or placate the ancestral spirits” (10).

The Brion Tomb, a family cemetery in San Vito d’Altivole designed by Carlo Scarpa and completed in 1978, encapsulates the idea of the labyrinth used as a sacred space perfectly. The tomb complex consists of 2,200 square meters configured in an L-shaped plan adjacent to an existing village cemetery. Agricultural fields envelope the cemetery complex and provide a boundary between the realms of the living and the dead. The tomb complex is composed of architectural and landscape components: propylaeum (gate), a portico with intertwined circles; arcosolium (tombs) for the mother and father, family tomb, and a gazon, which is a grassy area, meditative pavilion, set of perennial springs, watercourse, reflecting pools, chapel and priest cemetery filled with monuments (Figure 4A). Peter Homans, a psychologist at the Divinity School and author of The Ability to Mourn, defines monument: “Monuments contain a psychological core: they are also mnemic symbols. Experienced unconsciously as objects, the monument is a sort of compromise formation by means of which a group can unconsciously immerse itself in an experience of loss (loss of persons, ideas, ideals, or a lost ‘reality’, such as when a traumatic disaster destroys many members of the group) but not directly feel the full force of the pain which the loss arouses. The group is thereby enabled to immerse itself in the past (the loss itself), move on into the present (the construction of the monument), and from there to release into the future (the ability to mourn and return to, or create a rapprochement with, the great necessities of life)” (11).

Scarpa utilized a labyrinth metaphor to create experiences related to the affirmation of life in his design of the Brion Tomb. Scarpa said it was a place for “picnics and children playing” (Figure 4B). The chapel also hosted several weddings, according to the cemetery caretaker (Figure 4C). Other passages involved the journey of mourning, where users visited the site for quiet meditation and solitude. According to the article “The Life of Carlo Scarpa”, written by Giuseppe Mazzariol and Giuseppe Barbieri: “The labyrinth, so Nietzsche tells us in The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, is man, the life of man. Its lines unfold not only in space but also in the time of our life. In Borges’s Garden of forking Paths, with its Oriental protagonist, we see that the whole of time is an astonishing labyrinth: it has an entrance, a center, and an exit, and these perhaps coincide. A labyrinth is also the emblem of an ordeal successfully executed” (12).

The following content illustrates how design attributes of the Brion Tomb are examples of sacred architectural frameworks within a healing journey.

The entry gate and intertwined bronze circles

The propylaeum (Figure 4D,E) demarcates the transition from the village cemetery to the Brion Tomb. As you ascend the stairs you enter the portico and encounter intertwined bronze circles. The left circle is composed of red ceramic tiles (fire) and the right circle has blue tiles (water) (Figure 4F). Like the gates of Epidaurus, purification is realized by the presence of water. As Giambattista Vico states in New Science: “The Romans preserved an important vestige of such laws in the public rite of purification which they celebrated with water and fire to purge their city of all the citizens’ sins. They used these two elements to celebrate solemn nuptials. And they even considered the sharing of these elements a mark of citizenship, so that banishment was called the interdict of water and fire, interdictum aqua et igni” (13).

Within the portico, a glass door to the right descends into the floor and water below, which allows for passage to the meditative pavilion (Figure 4G). To the left, access is given to the gazon and arcosolium, which contain the tombs of the mother and father (Figure 4H).

The meditation pavilion, chapel and watercourse

Water is an important element in the healing aesthetic of the Brion Tomb. The meditation pavilion is accessed by a foot-bridge and surrounded by a lily pond (Figure 4I). The watercourse begins at a natural spring and flows from the arcosolium towards the lily pond and the meditative pavilion. The chapel is surrounded by a pool and connected to the adjacent priest cemetery (no tombs) by a segmented footbridge (14) (Figure 4J).

The waters symbolize the universal sum of virtualities; they are fons et origo, “spring and origin”, the reservoir of all the possibilities of existence; they precede every form and support every creation. One of the paradigmatic images of creation is the island that suddenly manifests itself in the midst of the waves. On the other hand, immersion in water signifies regression to the preformal, reincorporation into the undifferentiated mode of pre-existence. Emersion repeats the cosmogonic act of formal manifestation; immersion is equivalent to dissolution of forms. This is why the symbolism of the water implies both death and rebirth (4).

Du Sable Urban Ecology Sanctuary (unbuilt), Chicago, Illinois

Over the last decade healing gardens have been a popular element in healthcare design. But these healing gardens have been regulated to such passive activities as sitting and eating lunch. While the process of healing can incorporate passive “healing moments,” the opportunity to utilize a premium space for pro-active and therapeutic healing regimens should become a priority and focus of healthcare facilities. The Du Sable Urban Ecology Sanctuary [1993–1999], an un-built project, is an example of a therapeutic environment that could be utilized as a therapeutic healing tool to allow for collaborations between traditional, complementary and alternative healing modalities.

The Du Sable Urban Ecology Sanctuary was to be located in the shadow of the former Robert Taylor Homes, which in the 1990s comprised the largest density of public housing projects in the world. Then, the urban fabric and social cohesion of the neighborhood was degraded to the point in Chicago where the public domains were nearly deserted due to incessant shootings due to gun violence. Du Sable High School was the center of this vacancy, and located in the heart of the Robert Taylor Homes. Students there had experienced high rates of trauma. Carl Bell MD, a re-known child psychiatrist, conducted a study that identified rates of youth trauma at a nearby school: “…45% of high school students had witnessed a murder; 71% indicated that a friend or family member had been raped, robbed, shot, stabbed, and/or killed; and 27% of the students themselves had been victims of violence” (15).

Odis Richardson, a school administrator and facilitator of the Urban Ecology workshops, describes the plight of students and the social conditions surrounding the school: “You are a big tough boy, tough boy 15, a friend is knocked down dead, it happens within 2 miles from me every 6 days, and you have to come to school the next day. He is just your buddy, he is not your brother or your cousin and here you are at school and other people do not seem to care your best buddy was shot. They are going about their business, going to classes, joking and laughing and teachers are asking where is your homework and you are hurting inside. It is not like Downers Grove where a team of psychologists and sociologists come out and say how can I help you young man? Where can you at 15 go during your lunch break, or after school walk out there to the memorial area and in your own way, no church, no religion say “Hey friend, I miss you”. A big tough 15-year old boy, it would be kind of tough to do that in another place. It is important to us at an educational institution because if he does not get that out of him for the next two to five weeks we are going to have a hard time dealing with him. He is full of anger and trying to deal with death, he is going to bring that to every classroom. For us this will be a much-needed kind of space” (16).

The Du Sable Urban Ecology Sanctuary was conceived as a tool for healing, experiential education and community building. Dr. Emiel Hamberlin, the horticulture and biology teacher taught at Du Sable for more than 35 years and was students’ guiding light. He utilized gardens, exotic birds and a goat named Ms. Daisy to teach a basic human principle: the nurturing of life.

The school hallways were always busy with students walking while classes were in session. These students were called the “hall-walkers” with many of them experiencing trauma as well as friends or family members experiencing trauma, or witnessing violence and death. These students were too traumatized to sit and concentrate in class. The school hallways were safe and they socialized with people they trusted. Doc Hamberlin would engage these “hall-walkers” and say, “Do you want to come help me feed the peacocks, ducks, chickens, snakes?” Children’s fear turned to wonder as Doc Hamberlin led them into the 22,000 sq. ft. courtyard. He would bring them to an animal and say, “If you do not come here every day to take care of it, this animal will die.” (Figure 5A). Rebirth was witnessed as the student began to nurture life, return to class and eventually graduate. Gardens have long had an association with the sacred and renewal: only the religious vision of life makes it possible to decipher other meanings in the rhythm of vegetation, first of all the ideas of regeneration, of eternal youth, of health, of immortality. The religious idea of absolute reality, which finds symbolic expression in so many other images, is also expressed by the figure of a miraculous fruit conferring immortality, omniscience, and limitless power, a fruit that change men into gods (4).

A workshop process was essential to the design of the Du Sable sanctuary. To understand the origins of the problems, to understand each individual life’s course and begin to formulate solutions. A multi-disciplinary team of teachers, administrators, social workers, artists, contractors, ministers and a child psychiatrist and psychologist developed the sanctuary’s design. Eleven high school students contributed to the initial plan, and additional programming workshops engaging several hundred more students in the project (Figure 5B,C).

Today, violence in Chicago’s South and West Sides is worse than the time of the Robert Taylor Homes. Within these neighborhoods, violence and trauma profoundly affect children’s ability to learn and a teachers’ ability to educate. The Urban Ecology Sanctuary prototype was developed to possess programming that provided the “environment as a tool” for:

- Experiential learning/life’s lessons;

- Mental health programming/you can not learn if you are hurting;

- Self-reliance/resilience programming;

- Community building programming/community events.

The design was based on labyrinth principles of self-discovery and transcendence. Along the passageways the participant was always given a menu of experiences and encounters. Multiple activities could take place simultaneously. It would be possible to hear a concert, view art or hear a bell while on the way to the contemplative rooms or the picnic area or to commemorate the loss of a friend. The meeting room pavilion divided the courtyard space into four “outdoor rooms”. The following components were to be integrated into the courtyard (Figure 5D,E):

- Gardens, reflecting pools and animal support facilities reinforcing Dr. Hamberlin’s original concepts of ecology, nurturing and respecting life;

- Performance space, areas for murals, mosaics and sculpture (Figure 5F);

- Ceremonial gate, promenade and bell tower for celebrations and rituals such as graduation, basketball victories, weddings and commemorative services. The promenade can also be utilized for casual gatherings and ecology observation;

- Picnic area with a bust of Martin Luther King Jr;

- Forecourt for seating, dining, and a staging area for performances and ceremonies;

- Glass-enclosed seminar and exhibit room (Figure 5G);

- Stones engraved with timeless words of wisdom and a bust of Martin Luther King;

- Commemorative space to the student victims of violence containing a table of memory, a wall with the names of the victims of the violence, a stone of thoughts providing a testimony of the surviving victims of violence (Figure 5H);

- Three contemplative rooms allowing the students to reflect in solitude on life’s consequences and possibilities (15) (Figure 5I).

The Veterans Memorial Building, Cedar Rapids, Iowa

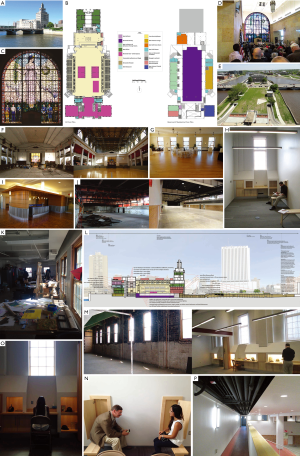

In 1927, the Veterans Hall, which functioned also as the local City Hall, was constructed in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, designed by architect Henry Hornbostel. The building became a center for civic, social and commercial activities in the community (Figure S1A,B). However, in the post-World War II era of suburbanization, the building was reallocated to functions that were primarily bureaucratic. The communal spaces fell into disrepair, and collective memory was regulated to the payment of parking tickets.

One important aspect of the building was its community mission—to honor the memory of those who gave the ultimate sacrifice in defending America’s freedom. Outside the main entrance and within the adjacent Memorial Room, the Grant Wood Stain Glass Memorial window was restored to greet visitors (Figure S1C,D).

This Memorial Window display is an allegory that reflects the ultimate sacrifice given by American warriors from the American Revolution to World War I. It appears as a maiden rising from waves of poppies and grain, who could be interpreted as Demeter, the Goddess of the Harvest who presides over the cycles of life and death.

Grant Wood was a World War I Veteran and art student in France. Wood would certainly be familiar with the symbol of the remembrance poppy, inspired by the poem “Flanders Fields”. This commemorative poppy symbolizes ultimate sacrifice. The red poppy is also the symbol of Demeter, whose guidance oversees rebirth.

In 2008, a catastrophic flood inundated the city of Cedar Rapids, damaging a thousand city blocks. Floodwaters peaked 16 inches below the Memorial Window sill. The Cedar Rapids Veterans Commission felt determined to transform the ruined building into an asset for Veterans, their families and the community. The rebirth of the Veteran Memorial Building began in 2010 and culminated with its opening in 2014.

The scope of the project included transformation of the 110,000 sq. ft. building, rehabilitation of an existing 75,000 sq. ft. parking garage and re-design of the public green (Figure S1E). The building program consisted of a restored memorial room and a restored 10,000 sq. ft. auditorium with a fly space, changing rooms (Figure S1F) and a ballroom (Figure S1G). New spaces were also added: behavioral health spaces (Figure S1H), a physical therapy room, workout rooms, a conference center, Veteran art museum, restaurant (Figure S1I), kitchen (serving 500 people on the auditorium floor) and large multi-purpose room (which was converted from the old armory space) (Figure S1J). A Veteran lounge, Veteran art studio (Figure S1K), offices, elevators, and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems were also added (Figure S1L). A mixed-use building accommodated the needs of an individual, small group to a large gathering of Veterans, Veteran families and the community.

Community is derived from the Latin word communitas, which means the feeling of fellowship with others, as a result of sharing attitudes, interests and goals (17).

Since reopening, the Veterans Memorial Building has played host a series of events including: Veteran art exhibits, leadership conferences and peer-mentoring sessions; Veteran performances, job fairs and writer workshops (Figure S1M); presidential rallies, weddings, receptions; and rituals for Memorial Day, the Fourth of July and, of course, Veterans Day.

The Veterans Memorial Building possesses space for physical therapy, aquatic therapy and behavioral health. The behavioral health environment provides solitude, cognitive therapy and peer mentoring—similar to Epidaurus in that it offers a menu of therapeutic activities centered on spirituality and ritual (Figure S1N,O).

A Veteran on his way to a physical therapy appointment, for example, can proceed to the auditorium for a performance. He then can go up to the restaurant for a meal. Afterwards, he can take an elevator to descend to the mezzanine, where he could view an art exhibit, athletic event or music in the armory multi-purpose space (Figure S1P). All of this would be possible proceeding or immediately after an appointment with behavioral therapists or peer mentors.

Such activities facilitate Veterans’ de-stressing, and make the appointment more efficient and shorten the duration of the Veteran’s therapies. This also shortens the line and waiting list for other Veterans to engage in healing therapies and associated activities.

Department of Veteran Affairs Healing Environment Design Guideline (VAHEDG)

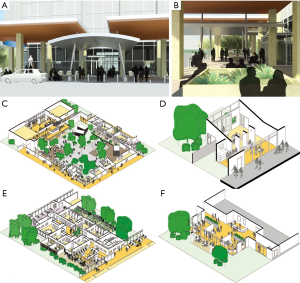

The VAHEDG, a design guideline, was created for the purpose of collaboration between Veterans, medical providers, VA facilities staff, architects, and engineers in the creation of healing environments for VA medical centers and VA community based outpatient clinics (CBOC). A healing environment facilitates a Veterans’ healing journey by fusing therapeutic environments with healing programming for the restoration of their mind, body, and spirit.

The Office of Construction and Facilities Management of the Department of Veteran Affairs commissioned this forward-thinking healing environment design guideline. The VAHEDG will influence all new construction and rehabilitation of all 168 VA Medical centers and 1,050 CBOCS the largest healthcare system in the United States. Gary Fischer, a VA senior healthcare architect and in charge of the VAHEDG explains the importance of producing the design guideline: “The impetus for the HEDG began in 2010 when VA launched a major initiative with the formulation of the Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC & CT). The term ‘Healing Environment’ was being applied to all facets of the physical environment and the associate facility planning and design work and it became clear there was no common definition or common understanding of what constitutes a ‘healing environment’. In addition to OPCC&CT the VA Environmental Management Service (EMS) was initiating efforts to define and describe ‘healing environments’ in VA facilities.”

A healing environment (HE) should encompass the whole facility, with each room and adjacent exterior element contributing to a different aspect of a Veteran’s healing (Figure 6A,B). Not every day is the same in a healing journey with stress related to family, job, and other personal issues that may complicate therapies related to wounds acquired during service. To reduce a Veteran’s stress the guidelines have identified seven design principles that compose a healing environment:

- Provide a therapeutic environment;

- Create a Veteran—embracing environment;

- Provide direct connections to nature;

- Design spaces and structures to reflect region and community;

- Be patient-centered;

- Provide a safe and supportive work environment for VA staff;

- Utilize state-of-the-art technologies to enhance the user experience (18).

Veteran traditions are historically steeped in ritual, commemoration and spirituality to honor the deeds and memories of fallen warriors: funeral pyre and games honoring of Achilles, funeral oration of Pericles, and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Commemorative rituals of remembrance are collectively celebrated by American society on Memorial Day and Veterans Day. Dr. James F. Munroe, Ed.D., a Boston VA psychologist took Vietnam Veterans to the Vietnam Memorial Wall for 10 years. Munroe utilized the Wall as a therapeutic tool for resolving loss and healing. Munroe recounts the Veterans visits to the Wall: “Vets stand looking at a name or a group of names and remember. They tell the stories that bring the names back to life. They talk about who the person was and the good times they had. They talk about the day of loss and what happened. The Wall marks that day. It marks many thousands of days” (18).

To support Veteran rituals the VAHEDG incorporated a courtyard space typology, a therapeutic courtyard, containing exterior components such as: ritual space, a story telling pavilion, a commemorative pavilion, and areas for dining and sitting (Figures 6C). While these components have no religious affiliations by definition this is sacred space to the Veteran. Utilizing contiguous interior spaces along the perimeter of courtyard in conjunction with the courtyard components a patient-centered healing narrative is created. For example, the chapel has immediate access to the courtyard and rituals, commemorative pavilion and storytelling pavilion. Thus, the chapel can be utilized directly into a commemorative ritual (Figure 6D). Other contiguous healing environments such as the mental health clinic and small waiting rooms/ meditative rooms can also be utilized with the exterior components for therapeutic purposes (Figure 6E,F). Like with in a sacred labyrinth, Veterans are given choices, a fork in the road, to comprise their healing journey. For every day is not the same.

Conclusions

Since the beginning of society, humans have utilized place and spirituality to heal both individual and collective wounds. At Epidaurus, spirituality was the primary healing tool, although it was also recognized that other complementary activities and environments were critical for healing. The builders of Epidaurus also knew that views of nature and natural light were important to pilgrims’ healing process—long before the effects of such design principles were quantified.

Stress is the origin of many ailments and inhibitor of effective healing modalities. Healing environments as a tool for meditation, prayer and rituals will allow a patient to de-stress before meeting the medical provider, and make the therapy more efficient, resulting in shorter therapy duration and increased healing efficacy. Healing Environments are the embodiment of aesthetics and should become an indispensable tool for medical providers in the healing of the mind, body, and spirit allowing an individual and the family to comprise their unique healing narrative.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all those who have had the courage to overcome adversity and the healers for inspiring and guiding our work. In addition, I would like to thank my wife Anna, a medical doctor, for sharing her insights in delivering healing in these turbulent times of American Medicine. We want to extend our gratitude to the contributions, compassion and creativity of Mathew Devandorf, in aeternum.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Harper D. Aesthetic. Online Etymology Dictionary c 2001-2017. Available online: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=aesthetic

- Anderson JL. An Introduction to Japanese Tea Ritual. New York: State University of New York Press, 1991:374.

- Hamilton DK, Orr RD, Raboin WE. Organizational transformation: a model for joint optimization of culture change and evidence-based design. HERD 2008;1:40-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eliade M. The Sacred and The Profane: The Nature of Religion. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987:256.

- Charitonidou A. Epidaurus: The Sanctuary of Asclepios and The Museum. Clio Editions, 1978:13.

- Papadakis T. Epidauros-The Sanctuary of Asclepios. 2nd edition. Munchen-Zurich: Schnell & Steiner, 1972.

- Tomlinson RA. Epidauros. 1st edition. Austin, Texas: University of Texas, 1983:18.

- Tick E. The Practice of Dream Healing: Bringing Ancient Greek Mysteries into Modern Medicine. 1st edition. Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books, 2001:165.

- Kern H. Through the Labyrinth: Designs and Meanings Over 5,000 Years. Munich, Germany: Prestel Publishing, 2000:27.

- Mumford L. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. San Diego, California; New York City, New York; London, UK: Mariner Books, 1968:6.

- Homans P. The Ability to Mourn: Disillusionment and the Social Origins of Psychoanalysis. 1st edition. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1989:271.

- Barbieri G, Giuseppe M. The Life of Carlo Scarpa. In: Dal Co F, Mazzariol G. editors. Carlo Scarpa - The Complete Works. New York City, New York: Electa/Rizzoli, 1984:22.

- Vico G. New Science: Principles of the New Science Concerning the Common Nature of Nations. 3Rev Ed edition. London, UK; New York City, New York: Penguin Classics, 2000.

- Alt P. The Brion Tomb - An Allegory of Marriage, Divinity, and the Timelessness of the Soul. Chicago, Illinois: 2005-2017.

- Alt P. Death and rebirth in Chicago: the Du Sable High School Urban Ecology Sanctuary. Architectural Research Quarterly 1999;3:321-34. [Crossref]

- Freeman A. Du Sable Urban Ecology Sanctuary Interview. Metropolis. Chicago, Illinois: WBEZ, 1995. Available online: https://soundcloud.com/altarchitecture/paul-alt-on-wbezs-metropolis

- Harper D. Community. Online Etymology Dictionary, c 2001-2017. Available online: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=community

- Department of Veterans Affairs - Office of Logistics, Acquisitions, and Construction; Office of Construction and Facilities Management; Office of Facilities Planning Facilities Standards Service. Healing Environment Design Guideline. Washington DC. 2017;19:164.