Barriers to palliative care for advanced dementia: a scoping review

Introduction

Dementia is a progressive, incurable, neurocognitive disorder and one of the leading causes of death. The appearance of dementia and its progression over time differ between patients. The end stage of dementia, advanced dementia, is terminal, yet is often not acknowledged as a terminal illness. During this terminal stage, families and staff must cope with end-of-life (EOL) issues and decisions, similar to other terminal diseases (1-3).

Despite the suffering and short life expectancy, many people with dementia do not receive the level and type of health care appropriate for their terminal situation (1,4,5). Through the use of advanced technology, medical treatment can postpone death in some cases. Yet these methods are not always welcome, as they can prolong suffering, cause stress and pain, and increase patient and caregiver burden, with no significant benefit. Medical professionals are oriented to prevent death, yet this approach does not take into account the impact of treatment on quality of life, as well as the results of such treatments. Often, the patient’s burden and preferences are not considered and do not receive their appropriate weight and value (1,6). People with dementia are often discriminated against in terms of receiving palliative and EOL care, compared to other terminal diseases, where the system considers palliative care to be the norm (7-9).

Acceptance of the need to apply palliative care to people with dementia is becoming more and more accepted among healthcare professionals and in healthcare settings, yet implementation is often lacking, resulting in over-aggressive treatments, with limited or no benefit to the patient and under-treatment of symptoms (10).

The oldest old have a lower rate of referral to palliative care services. For example, a report from a national survey in England found that only 15% of all patients receiving palliative care belonged to the old, old age group, 85 and over, while they account for 1/3 of deaths and have a high prevalence of dementia (8). There are lower rates of referrals of people with dementia to palliative care or hospice, compared to other terminal conditions. Formal palliative care services are lacking in most nursing homes (NHs). Moreover, although hospice and palliative care enrollment of people with dementia has increased over the past decade, many barriers to accessing palliative care persist (2). In the US among 474,829 NH residents with advanced cognitive and functional impairment lack of advance directives were associated with burdensome transition (hospitalization) in the last 90 days of life (11).

The aim of this scoping review was to explore the barriers towards implementation of palliative care for people with dementia.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review in order to map the current literature and identify the nature and extent of research evidence related to barriers associated with the implementation of palliative care to people with dementia.

Search strategy

The review comprised both non-research and evidence based articles, to ensure that all aspects of the topic were reviewed. We included non-research based articles containing opinions and debates among stakeholders in the field that were published in the professional literature, as much of the literature on the subject is linked to attitudes. Additionally, disciplines other than health care, including social work, were included due to the relevance of their contribution to the subject.

We conducted a search of the following electronic databases: PubMed and CINAHL. In addition, we searched Google Scholar in order to include relevant grey literature and scientific journals that are not included in PubMed or CINAHL. The search strategy was limited to English language publications between the years 2000–2016. The terms “dementia” and “palliative care” were used as key words. All publications that did not include the subject of barriers to implementation of palliative care for people with dementia in the Abstract were excluded. The full texts were then read and reviewed to identify publications that discussed barriers as the primary subject.

The literature search was conducted by the primary author; while the review and categorizing of the articles into themes took place separately by all of the authors, followed by a discussion, where a consensus was reached.

Data synthesis and data collection process

Given the heterogeneity of the studies, we used a narrative synthesis approach to summarize and map the literature. Articles were included if they examined healthcare provider perceptions towards barriers to palliative care among people with dementia. Articles whose aims were not directed primarily towards barriers to palliative care in people with dementia were excluded. Detailed information of the included articles was then categorized by the themes of the barriers to palliative care. The quality of reviewed articles was not assessed, as the purpose of a scoping review is to scan the current literature in order to determine what has been reported and what needs to be investigated related to a specific topic.

Results

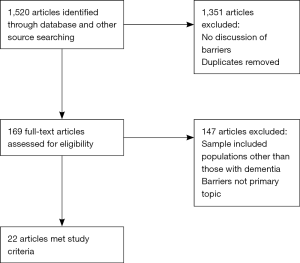

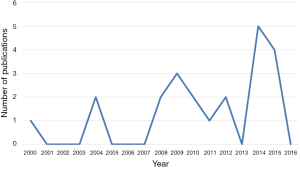

A total of 1,520 articles were reviewed for inclusion using the keywords: dementia and palliative care. The articles were then screened and further eliminated after review of the abstracts, with 169 retained for further reading. Of these, 22 publications were selected that met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). As can be seen in Figure 2, there was a significant increase in the number of publications addressing this topic, especially in 2014 and 2015.

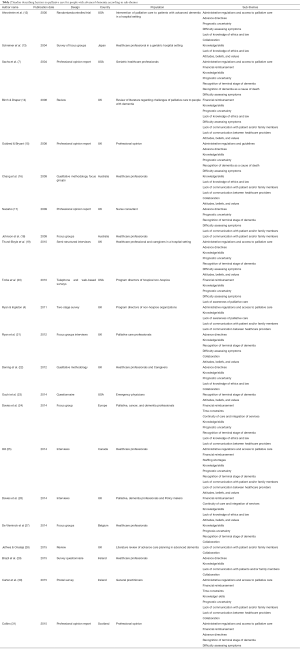

Most studies originated in Europe (n=14) or in North America (n=5). Studies predominantly used qualitative or mixed designs. We found one randomized controlled trial, two reviews, four professional opinions, and 15 surveys. The majority of the articles referred to older adults from the community and older adults in NH settings. Study populations included health professional staff and policy makers relating to palliative care for people with dementia.

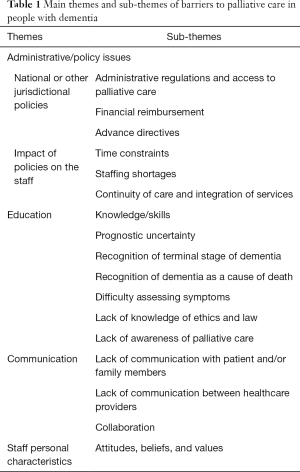

Four main themes of barriers were found in the 22 publications included in this review (4,7,12-31). These themes and their sub-themes are detailed in Table 1. In Table 2, the 22 publications included in this review are listed in chronological order from oldest to newest publication. Four main themes of barriers were found among these studies; administrative/policy issues, education, communication, and staff personal characteristics.

Full table

Full table

Administrative/policy issues

The first main theme is administrative/policy issues. This theme was further divided into national or other jurisdictional policies and the impact of policies on the staff. Under national or other jurisdictional policies, three sub-themes were found: administrative regulations and access to palliative care, financial reimbursement, and advance directives.

Administrative regulations and access to palliative care

Lack of access to palliative care was identified in our review as the primary barrier to implementing palliative care for people with dementia. Lack of access to palliative care reflected an administrative or policy deficit in the structure of the healthcare system (7,12). Increased attention has been paid more recently to regulations and resource shortages. One of the reasons mentioned was the lack of advance directives, reported as a barrier across time. These administrative and policy issues were global in nature and reported in Europe and North America (19,25).

People with dementia often die without the benefit of access to hospice care, thus they are at high risk for inadequate EOL care. For example, a study from 2001 found that only 7% of people with dementia in the USA were enrolled in hospice (7). The development of policies and administrative regulations related to EOL care for people with dementia evolved slowly, with guidelines stipulating equal care and availability of palliative care to those with dementia similar to others with terminal diseases (15). The Alzheimer Society in Scotland reported equal findings, adding that people with dementia face discrimination in care due to a lack of targeted services and variations in standards of palliative care that do not include people with dementia (31). In 2008, evidence began to be reported about strategies and programs targeting patients with terminal illnesses, such as dementia. Such programs included access to hospice services when patients begin to decline in function and a shift in goals of care from curative to comfort care. Indeed, the Annual Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society reported in 2009 that almost all hospice programs and 72% of palliative care programs treated people with dementia at least once within the past year (4).

While hospitals were and remain oriented towards the treatment of acute illnesses, hospital staff often attribute hospital admission of patients with dementia as a reluctance of primary care and NHs providers to take responsibility for the care of deteriorating patients. On the other hand, primary and home care staff transfer patients to acute care hospitals due to a lack of resources necessary for caring for these sicker patients, and sometimes because of pressure from family caregivers. Hospital staff tends to focus on the here and now, often neglecting future implications, while patients are repeatedly re-admitted due to an ongoing chronic gradual decline (19).

Financial reimbursement

Results from multiple nations suggest that patients with dementia have decreased accesses to funded palliative care compared to other patients nearing the end of life. Funding barriers that surfaced in our survey included the structure of funding models for dementia care, funding shortfalls in dementia care, and limits placed on funding of services accessed in community settings.

With respect to barriers inherent in the structure of funding models for dementia care, we identified three studies, all from North America (7,20,25). Financial incentives and disincentives built into the American healthcare system often work directly against the provision of palliative care to people with dementia, especially in NHs. For instance, although Medicare and Medicaid patients with dementia often need more staff time and resources than other NH residents, this is not reflected in Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement for services provided in NHs. In fact, when patients with dementia are transferred to a hospital, the nursing facility not only avoids extra costs but also is reimbursed for reserving the bed. In addition, treating physicians who transfer patients to the hospital receive a larger reimbursement for an admission visit compared to a NH visit (7).

The difficulty of providing home-based services to patients with dementia, who were not yet eligible for hospice has been reported. Insurance mechanisms do not adequately address the gap between skilled, community home-based services required by patients in an advanced state of dementia, and hospice services which require patients to be in an end stage of dementia (20).

We identified two examples of funding shortfalls. The first was a survey of general practitioners (GPs) across Ireland conducted in 2015. Survey results showed that funding shortfalls were perceived as a key barrier to palliative dementia care across primary care, due to limited time for quality communication with patients with dementia, as needed for EOL discussions, as such discussions are not included in reimbursement calculations. One proposed solution was that GPs request additional time for clinical assessments (30). The second study, from Canada, reported that most provinces cover the cost of some but not all medical needs. Therefore, people without enough funds could be prevented from accessing palliative care, and would then turn to acute-care hospitals, which cost less since they are covered by health plans (25).

EOL care often creates confusion or conflict as to who bears the responsibility for funding care and patient support. This is a particular challenge as people with advanced dementia are frequently not categorized as having a terminal condition (24,26).

The barrier of limits placed on funding of services accessed in community settings was identified in two publications. In Scotland, the government has committed, as of 2015, to ensure that all those with dementia receive free personal care when needed. However, complex care is currently provided in a number of hospital and community settings. The result is that those receiving care in other settings, including home care, will be required to pay their costs (31). In addition, although palliative care has been reported to improve quality of life, there is a suggestion that there is a risk of drift towards “economic euthanasia”, where patients might be denied appropriate health services due to perceived added expense of palliative care (14).

Advance directives

Advance directives are one of the keystones of palliative and EOL care for terminally ill patients, as they take into consideration the patient’s active role in decision-making, based on the patient’s own wishes related to care preferences and priorities. Advance directives are especially important for patients with dementia due to the cognitive deterioration characterized by the disease, ending in the loss of decision-making capacity. There is evidence to suggest that people with dementia are less likely than those with some other terminal illnesses to have advance directives (15,17,19-21,29,31). In addition, having advance directives was found to be associated with higher levels of satisfaction among all stakeholders (28). Having an advance directive may dramatically influence the attitude to care, as physicians in New York state reported being reluctant to avoid life-sustaining treatments or other aggressive maneuvers for such patients in the absence of a formal written advance directive, even when the physicians knew the gravity of the patient’s illness (12).

Advance directives and care planning should be the beginning of a communication process that may be of particular value for relatives and caregivers of people with dementia (19). However, evidence shows that GPs’ willingness to discuss advance care planning is inhibited by concerns regarding the readiness of the patients/families to make such decisions. The need for training related to how to initiate a conversation effectively about EOL planning and the need for a standardized advance directive’s format was cited (29). One study investigated the experience of healthcare staff working in palliative care in the UK related to advance care planning for people with dementia. Providers advocated for developing trusting relationships with key people, especially family, over an extended period, in order to facilitate decision making around palliative care (21). Interviews with health professionals from a wide range of settings point out a variable awareness of advance care planning, with little evidence that patients at any stage of dementia were asked about their wishes. Advance care planning was not occurring routinely (22).

Having formal advance directives usually promotes the process of decision-making. However, conflicts may arise, including the possibility that families may refuse to follow the wishes listed on their relative’s advance directive, as shown in a study from Canada (25). In this study, the family-staff conflict was not a statistically significant barrier to palliative care, in contrast to other findings in the literature. In the absence of advance directives, the responsibility of treatment decision-making falls on the healthcare professionals, although families can express their opinions. In order to avoid conflict, it is usual to have a discussion in order to reach a consensus on the best way to proceed (31).

Impact of policies on the staff

Three sub-themes were found related to the impact of policies on the staff. These include time constraints, staffing shortages, and continuity of care and integration of services.

Time constraints

Time constraints were found in the literature to be another barrier to the provision of palliative care in this patient population. Time is seen as a resource necessary for the provision of good palliative care but was found to be in short supply. In primary care, time constraints are a major concern that affects dementia care. Time pressure was also cited as an important barrier to shared decision making in clinical practice. The constraint of time for consultation has been recognized as limiting appropriate assessments, needs, and assessment of the wishes of older adults, leading to poor dementia care. Such obstacles caused diagnostic delay and prevented appropriate care management (24,30).

Staffing shortages

Staffing shortages and the need for more time to provide care emerged from interviews with health staff in a Canadian study, and was expressed by nearly all of the participants as a barrier to palliative care (25). Staffing shortages were linked to the need to spend more time with each patient due to the nature of the care needed in order to provide quality care to patients with dementia. Shortage of staff was related to decreased satisfaction with the quality of patient palliative care. When staff was able to focus less on fulfilling tasks, then they were more able to have meaningful interactions that sometimes decreased the need for pharmaceutical interventions (25).

Continuity of care and integration of services

Continuity of care refers to the way services and systems should work together and integrate palliative care. Dementia care requires health and social welfare systems to work together so that care can be holistic. However, patients and their caregivers may face difficulties related to navigating the integration of two complicated systems. Poor integration of services and limited collaboration was reported in a qualitative study that included healthcare experts from five European countries (24,26).

Education

Seven sub-themes were associated with educational barriers to palliative care in this population. They included: knowledge/skills, prognostic uncertainty, recognition of the terminal stage of dementia, recognition of dementia as a cause of death, difficulty assessing symptoms, lack of knowledge of ethics and law, and a lack of awareness of palliative care.

Knowledge/skills

The topic of palliative and EOL care has gained a stronger foothold in medical and nursing school curricula, as well as in the public media. However, increasing continuing education is needed for both professionals and the wider community in order to acquire the special skills necessary to care for people with dementia, with special attention to palliative and EOL care skills (4,7,14,15,19,25). On the organizational level, palliative models and programs that serve people with dementia are spreading, yet some evidence indicates that confusion around how and when to deliver palliative care is a widespread problem (25), accompanied by a lack of referrals from families or healthcare providers (20). Monitoring and evaluating EOL care with quality improvement and outcome measures are skills that healthcare providers should have, as the uncertainty around benefits and outcomes may hinder the delivery of palliative care (20). For example, emergency department physicians were found to view palliative consultation as not appropriate and did not refer patients to palliative consultation due to their attitudes, misconceptions, and lack of knowledge (23).

Limited knowledge and skills also relate to a lack of knowledge about the efficacy and necessity of palliative care for these patients. There is a lack of consensus among professionals working in the field as to whether palliative care is appropriate for this population. Providers have reported being fearful of the risks involved in providing this kind of care (21,24,25). Davies et al. (26), Jethwa et al. (28), and Dening et al. (22) add that training and organizational mechanisms should address the level of confidence in providing palliative care as well as skill development. In addition, Hill found that most staff did not know the difference between palliative and EOL care (25).

Prognostic uncertainty, recognition of the terminal stage of dementia, and recognition of dementia as a cause of death

In addition to limited knowledge regarding geriatric and palliative care, there are widespread misconceptions related to the disease and its progression. Dementia was often not recognized as a terminal illness and cause of death. Many did not understand the trajectory of the illness, were uncertain in estimating its prognosis, and so could not identify its end stage (7,12,14,15,17,19-24,27,31). Gaps in knowledge and inadequate palliative care training, along with the difficulties in prognostication, lead to missed treatment opportunities appropriate for the implementation of palliative care (15). Lack of provider and family awareness concerning the identification of when the patient has deteriorated and is at an end stage of the illness is also a barrier which leads to low levels of referrals and late referrals to palliative EOL care (20,25).

Difficulty assessing symptoms

Health practitioners need to be able to recognize the clinical features and symptoms associated with advanced dementia (15,20,21). Due to cognitive and communication deficits caused by the natural course of disease, it is not possible to know with any certainty what the patient experiences. This situation gets even harder as the patient’s ability to communicate deteriorates. Behavioral problems that frequently arise in dementia make it more difficult to provide palliative care to this population (7,12,21). Staff members who do not have the skills to recognize the needs for palliative care may offer inappropriate care, which puts people with dementia at risk for under-recognition and under-treatment of symptoms (14,17). Studies report that hospitals provide less pain control to patients with advanced dementia. Evidence from NHs shows that the majority of older adults living in NHs have some degree of pain, with underuse of pain scales developed to target this population (19,21,31).

Lack of knowledge of ethics and law

Studies have shown that there is a lack of knowledge related to the ethical and legal implications associated with clinical decision-making and advance directives (13,14,26). This might be associated with a lack of confidence and fear that can lead to the avoidance of palliative care (22,24). Physicians are more likely to decide to continue active treatment due to a fear of legal consequences, specifically being accused of neglect and cessation of care (12,14,26). Lack of clarity about the goals of care imposes ethical dilemmas that might bring well-meaning clinicians into conflict with the law (14,16). Ethical issues associated with dementia care, most notably withholding or withdrawing treatment, arise among the issues about boundaries between curative, palliative, and futile care (14), and might be in conflict with local policies (16). A study from Japan reports that physicians’ perception of legal concerns was a major barrier to improving EOL care (13).

Lack of awareness of palliative care

Lack of awareness of palliative care options is primarily due to deficits in the education of health providers as well patients’ relatives. In addition, poor collaboration between services and a lack of awareness of different services exists within health organizations. This lack of awareness leads to low referrals or late referrals of people with dementia to palliative care (4,20).

Communication

Inadequate communication and lack of collaboration with family members and between healthcare providers was found as a major barrier to palliative care. Communication with the patient/family is cited as a key element of high-quality EOL care by patients and caregivers (13,14,29). In order to obtain quality care, staff must have highly effective communication and collaboration skills, with all stakeholders, including the patient, staff, and family members. Multi-disciplinary teams collaborating together in partnership with families is crucial in order to plan and deliver appropriate care that meets the individual needs of each patient, matching their values and preferences (14). Negotiation and discussion may assist in achieving consensus and decision-making related to goals of care, while lack of effective communication may lead to conflict, either between staff, or with families (16,30). Conflicts were identified in the literature as a significant barrier to palliative care for the patient with dementia.

Lack of communication with patient and/or family members

There is a discussion in the literature about whether and when patients should be informed of their diagnosis. This suggests that sensitive communication is beneficial as patients may be able to participate in decision-making, before cognitive deterioration takes place. Most of those who were opposed to directly informing the patient felt that such communication could lead to depression and anxiety (4,14,17,18). A survey among Irish GPs, found divided opinions regarding whether the GP should initiate and encourage discussion with the patient, with most survey participants acknowledging the need to improve family involvement (29). Lack of communication with the family might inhibit the implementation of a palliative approach. This lack of communication has been linked to poor symptom management and a high rate of inappropriate hospitalization, lack of definition of goals of care, and conflict between caregivers and health staff as to different medical aspects and views opposed to the patient’s wishes (25,28).

Some of these conflicts were attributed to families misunderstanding the nature of the course of dementia, unrealistic expectations of a positive prognosis, uncertainly regarding the patient’s wishes, and refusal to follow the patient’s documented wishes. All of these conflicts lead to the demand for aggressive treatment that was opposed to the healthcare provider’s perceptions of best practice (25).

Lack of communication between healthcare providers

Communication problems are prevalent among staff, leading to poor team collaboration, disagreements, and stress, especially with staff members who were not trained in palliative care (4,24,25,30).

Studies also discuss conflicts between staff from different disciplines and different training, alongside poor collaboration and communication. Time pressure, funding mechanisms, integration of services, and diffused responsibility were also found to be a cause of conflict between decision-makers and a cause of tension leading to a lack of trust, disorganized care, and hesitancy to address a palliative approach (25,30).

Collaboration

Collaboration seems to be a struggle in many national healthcare systems, including the UK, Ireland, Belgium, and Australia (16,21,22,26-30). The importance of different healthcare providers working together as multidisciplinary care teams in order to achieve high quality palliative and EOL care for people with dementia was discussed in a study from Australia (16). Team collaboration was thought to be necessary in order to address the variation and unique combination of needs of people with dementia and their treatment preferences. Collaboration is necessary so that the system has the ability to tailor a care plan that considers a range of choices (16). Another study described common challenges providing palliative care across five countries in Europe. The investigators found that there were structural difficulties and ineffective mechanisms when trying to integrate services (26). Evidence shows poor team coordination alongside a lack of collaboration between primary care providers and specialists (27,28,30).

There is a wide range of healthcare settings for EOL care for people with dementia but there is little collaboration and communication between them, where providers have little knowledge of each other’s activities (22). The National Council for Palliative Care in the UK has a section charged specifically with improving the provision of EOL care for advanced dementia. The Council is working on strengthening ties with pre-existing dementia and palliative care services in order to ensure coordination and communication between services. They also issued a declaration in 2012 that dementia is a national priority (28). Despite these efforts, interviews with clinicians from Europe in 2015 revealed limited collaborative working strategies between palliative care services and geriatric specialists. Strong leadership was identified as a facilitator both at a clinical practice level as well as at a strategic/policy level (29).

Staff personal characteristics

The final major theme is staff personal characteristics. This includes the attitudes, beliefs, and values of the staff.

Attitudes, beliefs, and values

Attitudes regarding palliative and EOL care are often driven by awareness of the illness, its treatment and expected outcomes (13,16). Decisions may be linked to feelings of guilt and anxiety of family members and even staff (14). Healthcare providers make care decisions based on their own care preferences in a similar situation or based on previous experience. Different attitudes between healthcare professionals and relatives were found to be a barrier that may hold back palliative care. Religious beliefs, cultural background, and personal values may guide and influence the decision process (19,23). In a finnish study, the relationship between healthcare provider background and EOL decision was examined, showing a significant influence on care approaches (14).

Many physicians tend to focus on the acute, potentially reversible illness and avoid the terminal aspects of the patient. The decision to withdraw or withhold is much more difficult than the decision to commence or continue treatment (14). NH staff from the UK reported experiencing feelings of fear of death (19), while NH staff from Canada reported being afraid to talk about death (25). Both types of fears can lead to avoidance of discussions related to EOL care.

Discussion

Today, chronic terminal diseases, including an increase in the prevalence of dementia, are associated with the majority of causes of death in the western world (29,32). There is a significant difference in the attitudes of healthcare providers toward accepting dementia as a terminal disease and cause of death, compared to other terminal illnesses (1,33,34). The estimated number of people dying from dementia may be five times higher than reported by the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (34). The estimated cause of death is based on death certificates, which often fail to list dementia as a cause of death. Physicians tend to report the immediate cause of death, without reporting the underlying one (dementia), reflecting a lack of recognition and inaccurate perception of the terminal nature of the disease (34).

One of the causes for failure to recognize dementia as terminal is “prognosis paralysis”, defined as a lack of ability to determine prognosis due to the uncertain nature of the disease (35,36). This paralysis frequently results in prognostic uncertainty and inadequate EOL care due to delaying or not recommending palliative care, as well as exposing patients to uncontrolled symptoms, over-procedural and pharmacologic treatment, futility of care, and unnecessary suffering (37).

On the organizational level, evidence from the USA, Europe, and Canada, describes organizational structures and policies not in keeping with a palliative care approach (7,19,25). In community settings, the integration of palliative care into NHs offers a potential solution to hospice eligibility, with adequate reimbursement for care, in a way that aligns with residents/caregivers’ preferences and needs (25). Assessment tools and protocols that are being used in NHs do not include palliative care components, with a lack of standardized assessment of terminal status.

Shortages of resources, including funding, reimbursements, and staffing were found to be significant barriers to the provision of palliative care. Investment in the workforce might be one potential solution in addressing the issue of qualified care. Interviews with health providers at community settings around the UK describe feeling of negative image of NH staff and poor salaries. Staff members report feelings of low confidence in their work and a low ability to make EOL care decisions. Some participants in the interviews describe the NH staff as focusing on basic physical care needs, with little motivation and compassion, failing to address psychosocial needs (38).

Staff needs to receive relevant education and training in order to deliver palliative care to people with dementia (16). In England and Belgium national health organizations developed training programs for staff education, improving palliative and EOL care (15,27). The Australian government is funding a program for primary health care to increase their knowledge and skills on the palliative approach to care (16).

Adequate time is another missing resource associated with good palliative care. A lack of time may hinder an extensive discussion of treatment options, especially in crisis and critical situations and may hinder the involvement of patients/families in decision-making, damaging the care process (30).

During the last decade, most western countries have promulgated laws considering limits of medical care for terminally ill patients, from the view of patient autonomy and dignity. The law determines patients’ rights for decision-making regarding the kind of care they prefer; and under certain conditions, the right to avoid care; as well as protecting the healthcare provider from lawsuits when providing EOL and not life-prolonging care (39,40). Because dementia is frequently not considered a terminal disease, most patients with dementia do not take advantage of these legislative approved opportunities and do not declare their preferences for future care (39,40). Such is the case with advance directives, an important aspect of palliative care. While NH managers are central to the implementation of palliative care, a survey in the UK found (41) that lack of knowledge and negative attitudes towards advance directives, underpinned by concerns regarding lack of perceived benefits to the person with dementia, prevented advance care planning. Currently managers do not view obtaining advance directives as part of their role. In addition, a NH observational study in Belgium found that while many residents were eligible for advance directives, baseline levels were low and there was a lack of consistency between policy and practice (5).

Even when advance directives and do not resuscitate (DNR) orders exist, healthcare providers often lacked the confidence to follow the orders and to provide EOL care, citing fear of prosecution (38). NH managers add that they are reluctant to adopt palliative care approaches because of potential sanctions by health authorities that may sabotage certification and licensure, as well as fear of criminal prosecutions charging abuse and neglect of residents, and improper use of pain control substances (42).

The routine of curative care provides a safe and protected climate for healthcare professionals, thus avoiding uncomfortable and distressing discussions regarding death. This phenomenon has vast social and ethical implications, raising the question as to what is the morally right treatment for these patients (3).

Healthcare staff personal characteristics like age, gender, and past exposure were also found to be related to attitudes and practices regarding EOL care. This aspect is rarely discussed (14). Clinical practice does not exist in a vacuum. While regulations and guidelines should be enforced, compliance is often related to staff perceptions such as self-confidence and self-efficacy. There is a need to further explore the potential influence of personal characteristics, beliefs, values, and confidence related to the delivery of palliative care to people with dementia.

The debate and research regarding palliative care for people with dementia has been an issue in the professional literature for more than a decade, which shows its importance as well as its complexity. Yet the methodology of research included in this review could be improved. Most of the research settings were long-term care facilities or community settings, with only limited research on acute-care settings, thus preventing us from gaining a true and comprehensive picture of the issue.

Although palliative care for people with dementia is gaining gradual recognition among health professionals, as reflected for example in NHs and UK government policy (14), it is still not the consensus and lacks widespread implementation. This lack of implementation of palliative care for people with dementia is primarily discussed as an outcome of existing barriers, as found and reviewed in this scoping review. Yet, the way to overcome these barriers is not clear. These barriers exist on many levels, including the administrative and policy level, educational level, and communication.

We found three main missing aspects in the research of this field, which we consider to have a significant potential impact on the topic. The first aspect is the healthcare provider’s personal view, as their relationship with their patients is considered an ideal context for starting the process of palliative or EOL care (27). Personal characteristics have been found to be associated with differences in palliative care attitudes (14,19,23).

The second under-reported aspect relates to ethical dilemmas regarding the right to life and quality of life in advanced dementia (3). Few studies investigated the impact and characteristics of the individual healthcare provider as they affect the process of providing palliative care to people with dementia, and no study was identified dealing with ethical skills of the healthcare provider.

The last aspect we identified was the patient/family voice. We found that most studies were descriptive, focusing on the healthcare provider’s point of view. Healthcare providers did not perceive patient/family attitudes, priorities, and wishes as a significant barrier. However, understanding and addressing these attitudes is considered an important aspect of the palliative care approach.

Therefore, further research should be conducted to describe the impact of individual healthcare provider ethical and personal characteristics on the provision of palliative care to people with dementia, with special attention to understanding the limited consideration of the patient/family voice. We assume that gathering of this information may increase our understanding of this topic in a way that will contribute to improving the provision of quality care for this vulnerable population of patients.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell SL. Clinical Practice: Advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2533-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marcus EL, Golan O, Goodman D. Ethical issues related to end of life treatment in patients with advanced dementia – the case of artificial nutrition and hydration. Diametros 2016;50:118-37.

- Ryan T, Ingleton C. Most hospices and palliative care programmers in the USA serve people with dementia; lack of awareness, need for respite care and reimbursement policies are the main barriers to providing this care. Evid Based Nurs 2011;14:40-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ampe S, Sevenants A, Smets T, et al. Advance care planning for nursing home residents with dementia: policy vs. practice. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:569-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Volicer L, Hurley AC, Blasi ZV. Scales for evaluation of end-of life care in dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2001;15:194-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1057-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- House of Commons Health Committee. End of Life Care. Fifth Report of Session 2014-15. London: The Authority of the House Commons, March 2015. Available online: https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201415/cmselect/cmhealth/805/805.pdf

- Shaulov A, Frankel M, Rubinow A, et al. Preparedness for end of life – a survey of Jerusalem district nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2114-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van Der Steen JT. Dying with dementia: what we know after more than a decade of research. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;22:37-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1212-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahronheim JC, Morrison RS, Morris J, et al. Palliative care in advanced dementia: a randomized controlled trial and descriptive analysis. J Palliat Med 2000;3:265-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schreiner AS, Hara N, Terakado T, et al. Attitudes towards end-of-life care in a geriatric hospital in Japan. Int J Palliat Nurs 2004;10:185-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Birch D, Draper J. A critical literature review exploring the challenges of delivering effective palliative care to older people with dementia. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:1144-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouldred E, Bryant C. Dementia care. Part 3: end-of-life care for people with advanced dementia. Br J Nurs 2008;17:308-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang E, Daly J, Johnson A, et al. Challenges for professional care of advanced dementia. Int J Nurs Pract 2009;15:41-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nazarko L. A time to live and a time to die: palliative care in dementia. Nursing & Residential Care 2009;11:399-401. [Crossref]

- Johnson A, Chang E, Daly J, et al. The communication challenges faced in adopting a palliative care approach in advanced dementia. Int J Nurs Prac 2009;15:467-74. [Crossref]

- Thuné-Boyle ICV, Sampson EL, Jones L, et al. Challenges to improving end of life care of people with advanced dementia in the UK. Dementia 2010;9:259-84. [Crossref]

- Torke AM, Holtz LR, Hui S, et al. Palliative care for patients with dementia: a national survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:2114-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryan T, Gardiner C, Bellamy G, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the receipt of palliative care for people with dementia: the views of medical and nursing staff. Palliat Med 2012;26:879-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dening KH, Greenish W, Jones L, et al. Barriers to providing end-of-life care for people with dementia: a whole-system qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2012;2:103-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouchi K, Wu M, Medairos R, et al. Initiating palliative care consults for advanced dementia patients in the emergency department. J Palliat Med 2014;17:346-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies N, Maio L, Van Riet Paap J, et al. Quality palliative care for cancer and dementia in five European countries: some common challenges. Aging Ment Health 2014;18:400-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hill EM. Investigating barriers to access and delivery of palliative care for persons with dementia in London, Ontario. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2014;2455. Available online: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3784&context=etd

- Davies N, Maio L, Vedavanam K, et al. Barriers to the provision of high-quality palliative care for people with dementia in England: a qualitative study of professionals’ experiences. Health Soc Care Community 2014;22:386-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Vleminck A, Pardon K, Beernaert K, et al. Barriers to advance care planning in cancer, heart failure and dementia patients: A focus group study on general practitioners’ views and experiences. PLoS One 2014;9:e84905. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jethwa KD, Onalaja O. Advance care planning and palliative medicine in advanced dementia: a literature review. BJPsych Bull 2015;39:74-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brazil K, Carter G, Galway K, et al. General practitioners’ perceptions on advance care planning for patients living with dementia. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carter G, Van Der Steen JT, Galway K, et al. General practitioners’ perceptions of the barriers and solutions to good-quality palliative care in dementia. Dementia 2015;16:79-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collins J. Living and dying with dementia in Scotland: Barriers to care. Report February 2015. Marie Curie Cancer Care. Available online: https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/globalassets/media/documents/policy/policy-publications/february-2015/living-and-dying-with-dementia-in-scotland-report-2015.pdf

- Kapo J, Morrison LJ, Liao S. Palliative care for the older adult. J Palliat Med 2007;10:185-209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coleman AM. End-of-life issues in caring for patients with dementia: the case for palliative care in management of terminal dementia. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:9-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- James BD, Leurgans SE, Hebert LE, et al. Contribution of Alzheimer disease to mortality in the United States. Neurology 2014;82:1045-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dainty P, Leung D. An evaluation of palliative care in the acute geriatric setting. Age Ageing 2008;37:327-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold RM, Jaffe E. Why palliative care needs geriatrics. J Palliat Med 2007;10:182-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:321-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kupeli N, Leavey G, Moore K, et al. Context, mechanisms and outcomes in end of life care for people with advanced dementia. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doron D, Wexler ID, Shabtai E, et al. Israeli dying patient act: physician knowledge and attitudes. Am J Clin Oncol 2014;37:597-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hurst SA. Assisted suicide and euthanasia in Switzerland: allowing a role for non-physicians. BMJ 2003;326:271-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beck ER, McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, et al. Nursing home manager's knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about advance care planning for people with dementia in long-term care settings: a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Huskamp HA, Kaufmann C, Stevenson DG. The intersection of long-term care and end-of-life care. Med Care Res Rev 2012;69:3-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]