Using the ecological framework to identify barriers and enablers to implementing Namaste Care in Canada’s long-term care system

Introduction

Although long-term care (LTC) is a major end of life setting for older people in Canada (1), palliative care approaches have yet to realize their full potential here. A potential reason for this is that most LTC residents have cognitive impairment (2,3), and poor understanding of the end of life trajectory for these residents among LTC staff (4) continues to be associated with underuse of comfort care measures (5,6) and invasive non-palliative interventions, such as tube feeding, laboratory tests, and intravenous therapy (4,7,8). Over the last decades, organizations providing LTC have been urged to consider a palliative approach for residents with cognitive impairment (9). Such an approach would ideally emphasize: patient-centred care, optimal symptom management, advance care planning, psychosocial and spiritual support, family involvement, health provider education, continuity of care, attention to ethical issues, and timely recognition of dying (10).

New approaches to the end of life care of cognitively impaired LTC residents are increasingly being documented (11-13). Among these is a program called Namaste Care, a program tailored for residents who can no longer participate in traditional recreational programming (14) and an approach to end of life care (15). The Hindu greeting namaste, from which the program derives its name, encapsulates the program philosophy: “to honor the spirit within”. Namaste Care is most frequently offered as a group program, intended to run seven days per week, twice per day, for two hours each time. The program is usually coordinated by a nursing assistant, with drop-in assistance from other staff, family members, or volunteers. Given the group format, it may be possible to introduce Namaste Care without adjusting staffing levels.

During Namaste Care, program participants visit a room with soft music or nature sounds, lowered lighting, and pleasant scents. Some aspects of personal care (washing face, hands, and feet; grooming; and nail care) are included to facilitate an experience of gentle, caring touch. Continuous hydration and soft, sweet foods are offered to stimulate appetite and raise caloric intake (15). These aspects of Namaste Care align well with recommendations for palliative dementia care, including patient-centred care, continuity of care, optimal symptom management (14,16,17), and psychosocial and spiritual support (16,17). Simard suggests the program also promotes family involvement (15), communication (16), and assessment (17).

This approach to care has now been implemented in LTC homes and hospice organizations throughout the USA, and in the UK, Iceland, and Australia (18). Despite its apparent advantages, some organizations have faced challenges implementing Namaste Care (19,20). For example, among a group of five UK homes that implemented Namaste Care, four saw improvements in participants’ pain, behavioural symptoms, and the extent to which behavioural symptoms disrupted staff members’ work (17). However, one home saw an increase in unwanted symptoms such as pain and neuropsychiatric symptoms. This unsuccessful implementation was attributed to challenges within the leadership team (17). However, the homes that successfully implemented Namaste Care also reported implementation challenges, including: distributing the work, increasing knowledge of the program, encouraging busy staff to take time to participate, and changing practices that aligned poorly with the program (19). There is some evidence that similar, surmountable challenges have surfaced in other Namaste Care launches (20). Nevertheless, factors determining the success of Namaste Care programs have not been systematically studied.

The ecological framework

It is challenging to implement innovations in healthcare. A growing body of work aims to understand why some organizations succeed in this while others fail. An increasingly common approach is to classify factors that facilitate or impede successful implementation using an implementation determinant framework (21). One of these, the ecological framework (22), was originally developed to promote implementation success for health promotion and prevention programs. An advantage of this framework is that it is drawn from a review of relevant literature, and is therefore both evidence-based and comprehensive.

According to the ecological framework, the success of a program is influenced by characteristics of the innovation (e.g., compatibility with existing needs), characteristics of the providers responsible for the innovation (e.g., self-efficacy), and characteristics of the wider community, including the health care system. Program success is also influenced by the level of support for implementation (e.g., training and technical assistance) and by characteristics of the system within which the program is implemented, including general organizational factors (e.g., capacity to incorporate the innovation), specific practices and processes (e.g., formulation of tasks), and staffing considerations relevant to promoting program success (e.g., leadership and supervisory support). This broad, multi-faceted approach ensures attention to the various levels at which successful program implementation can be compromised or enhanced.

Something that distinguishes the ecological framework from other determinant frameworks is its sensitivity to the influence of the socio-political environment in which innovations are implemented. Since LTC is a setting in which the socio-political environment is known to influence adoption of knowledge and best practices (23-25) and ultimately quality of care (26,27), we considered the ecological framework well suited to identifying important implementation determinants of Namaste Care in this environment. We used the ecological framework to address the following research question: What are the perceived barriers and enablers to implementing Namaste Care in the Canadian LTC system?

Methods

Design

We used a qualitative interpretive design based on a template organizing style (28,29) to identify implementation determinants specific to the introduction of Namaste Care.

Ethics

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by two university ethics boards (Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board, No.15-092; University of Saskatchewan Behavioural Research Ethics Board, No. 15-267), and conforms to the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013. Study participants provided free, informed, written consent, as further described below.

Context and participants

This study took place prior to an 18-month evaluation of the acceptability and feasibility of Namaste Care in Canadian LTC homes. Two LTC communities (“sites”) participated; one in Hamilton, Ontario and the other in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. In Ontario, 127 residents lived at the participating LTC home, a non-profit entity owned and operated by a religious organization and affiliated with the regional health authority. Sixty residents lived at the participating LTC home in Saskatchewan, which was a private not-for-profit entity affiliated with the regional health authority.

To recruit, facility managers briefly reviewed the purpose of the study with prospective participants, and then invited them to attend a focus group. To ensure a diverse sample, three groups of participants were interviewed at each site: family members, nurses, and unlicensed health providers (i.e., nursing assistants and one recreation worker). A total of six focus groups were scheduled (3 groups × 2 sites). Prior to each focus group, the interviewer reviewed the purpose of the research, gave participants the opportunity to ask questions, and offered the opportunity to decline. No one declined. Across the two sites, a total of 15 family members participated; a few were spouses (20%) and the remainder, children or other relatives (80%). Most family members were female (80%). A total of 17 registered nurses (82% female) and 12 unlicensed providers (100% female) participated. Most unlicensed providers were nursing assistants (75%) and the remainder, recreation workers (25%).

Interviews

Focus groups were conducted in a private meeting room in each participating LTC home in December 2015. A member of the research team conducted the interviews at one LTC home (“site 1”) and a trained research assistant conducted the interviews at the other (“site 2”). The interviewers first introduced Namaste Care by describing its philosophy, elements, logistics and possible outcomes, noting that the group format ensured a staffing ratio similar to the current nursing assistant to resident ratio (1:8), and stating that additional drop-in support could be recruited from other staff members, volunteers, and family members. As the interview proceeded, participants were asked to describe perceptions of Namaste Care, to discuss their site’s strengths and weaknesses with respect to implementing Namaste Care, and to generate ways to address any identified weaknesses.

Data analysis

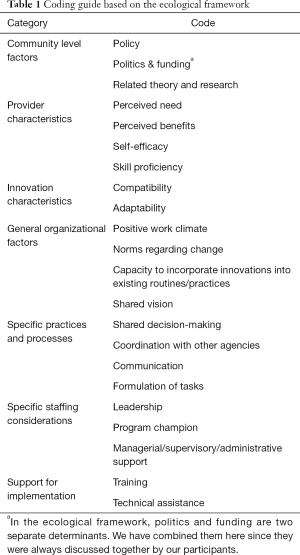

A deductive approach to content analysis was employed. In content analysis, transcript statements that convey particular meanings are condensed, interpreted (i.e., coded), and then further abstracted into sub-categories and over-arching categories (30). In a deductive approach (31), or template organizing style (28,29), data is evaluated for correspondence with a pre-existing template; in this case, the ecological framework (Table 1).

Full table

Results

Results are summarized according to the seven major categories of the ecological framework, each summarizing additional factors that could act to enhance or impede implementation success. The categories are: community-level factors, characteristics of health providers, characteristics of the innovation, general organizational factors, specific practices and processes associated with the innovation, staffing considerations, and supports for implementation (Table 1).

Community level factors

Community-level implementation determinants operate beyond the organization implementing the program and include health systems factors, such as relevant policies, politics, funding, and related theory or research.

Staff members at both sites mentioned several policies that might represent barriers to program implementation. One of these was a requirement for two-person lifts and transfers for some frail residents, which might be more difficult to coordinate if one nursing assistant was diverted to Namaste Care. Another potential barrier was the existence of infection control protocols, which were seen as difficult to observe in a daily group program. A third was a system-wide no-scent (i.e., perfume) policy. Namaste Care was seen as contravening this given a suggestion during the program overview that an essential oil diffuser might be used to create a pleasant scent in the room.

Family members at both sites also mentioned low government funding support for LTC as a potential barrier to implementation. At both sites, family members did not see it as realistic to implement Namaste Care without funding for additional staff. Nurses and unlicensed staff at both sites also commented that the program would be difficult to implement without additional staff, but did not specifically cite funding levels as a concern. With respect to related theory and research, a potential implementation enabler was that licensed staff at site 2 perceived Namaste Care as consistent with a palliative or comfort care approach. In addition, at both sites, family members suggested that the results of previous implementations of Namaste Care could inform the current implementation. See Table 2 for supporting quotations from interviewees.

Full table

Provider characteristics

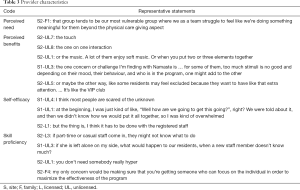

According to the ecological framework, it is important to successful implementation that providers perceive the program as needed and beneficial. Namaste Care fared very well in this regard (Table 3). All groups at both sites recognized the need for greater attention to LTC residents with late-stage dementia and commented on ways that Namaste Care could help to meet the particular needs of this group. Namaste Care was also perceived as offering several benefits, such as increased comfort and meaning.

Full table

Nevertheless, all site 1 groups raised concerns that the group format would undermine benefits. A frequently proffered example was that of someone with dementia becoming agitated during the program, and thereby reducing other participants’ psychosocial wellbeing. In addition, family members at site 1 and unlicensed staff at both sites expressed concern that diverting a staff member to Namaste Care would disadvantage residents who were not enrolled in Namaste Care.

Implementation-relevant provider characteristics also include skill proficiency and self-efficacy. With respect to skill proficiency, at both sites, unlicensed staff was concerned about relying on a casual workforce, although the way that this concern was expressed varied across the two sites. At site 1, unlicensed staff worried that coordinating Namaste Care would leave less skilled casually employed staff responsible for other work; in contrast, at site 2, unlicensed staff emphasized that it would be unwise to rely on casual staff to coordinate Namaste Care. Similarly, at site 1, family members were concerned that the most caring staff would be diverted to namaste care, whereas at site 2, it was emphasized that staff in Namaste Care must be caring. With respect to feeling capable of implementing the program, at site 2, licensed staff expressed a high level of self-efficacy, requesting that they be given responsibility for the program. At site 1, unlicensed staff expressed low self-efficacy and feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of implementing Namaste Care.

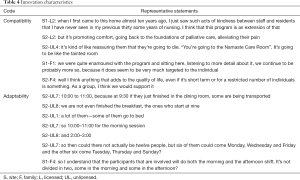

Innovation characteristics

The ecological framework specifies program compatibility with local interests and adaptability to local needs as additional implementation determinants (Table 4). With respect to compatibility, licensed staff from both sites said the program philosophy complemented an existing emphasis on positive relationships with residents and quality palliative care. However, at site 2, unlicensed staff believed the group format would discourage family involvement at the end of life, and perceived the emphasis on the end of life period as stigmatizing. Family members at both sites saw the approach as consistent with resident-centred and individualized care approaches.

Full table

Interviewees generated several adaptations to increase program viability. For example, family members at site 1 suggested offering the program to different residents in morning and afternoon, to reach more people. Unlicensed staff at site 2 suggested offering a shorter program at less busy shift times, running the program fewer days per week, and including some residents in a morning shift and some in an afternoon shift.

General organizational factors

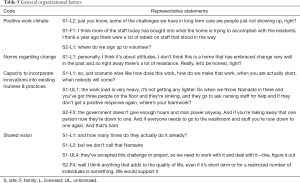

The ecological framework considers the following organizational factors as important implementation facilitators: a positive work climate, openness to change, ease of integration into practice, and a shared vision (Table 5).

Full table

At site 1, both licensed staff and family members commented positively on recent improvements in a culture of resident-centred care at the home. Nevertheless, each group also mentioned an absenteeism problem among unlicensed staff. Licensed staff expected that the home would have difficulty negotiating a change in practice; in particular, staff absenteeism combined with a generally high workload in LTC were seen as potential threats to a successful implementation of Namaste Care. Nursing assistants anticipated difficulty reorganizing their work (traditionally done in two-person teams) to accommodate the program, and family members also believed the program required extra staff.

At site 2, there were no explicit comments about organizational climate; nevertheless, interview transcripts gave evidence of a strong sense of camaraderie among both licensed and unlicensed staff. For instance, compared to site 1, there was a great deal of collaborative discussion (e.g., supporting or completing each others’ contributions) and humour was used frequently. Licensed staff and family members voiced a willingness to try the program, and all staff actively considered how to best accommodate the program. A few licensed staff members even voiced interest in volunteering time outside of work.

Specific practices and processes

According to the ecological framework, successful implementation is supported by specific organizational practices and processes. These include a high level of collaboration between managers and staff either prior to or during implementation, which may be manifest in shared decision-making, coordination with other community organizations, effective communication processes, and shared formulation of tasks (Table 6).

Full table

With respect to shared decision-making, both licensed and unlicensed staff at site 1 expressed concern that they were not involved in the decision to adopt the program and expressed interest in participating in future decisions. At site 1, family members asked to help decide which residents participate in the program; at site 2, they asked to be given the opportunity to describe perceived effects of the program on their own family members.

With respect to coordination with other agencies, family members mentioned the possibility of students and clergy lending support to the program. They also repeated a comment made in the overview of Namaste Care, noting that family members and volunteers could participate in the program.

All staff members highlighted the importance of clear and active communication about the program. At site 1, licensed staff expressed questions about feedback processes for the program, and conveyed interest in communicating with the management team and the research team. At site 2, licensed staff suggested creating a staff schedule for Namaste Care, and advised documenting the work done in Namaste Care. Unlicensed staff suggested considering the advantages and disadvantages of listing Namaste Care on the home’s activities calendar. They also recommended making a brief “snapshot” of resident care needs available to those working in the Namaste Care room. At both sites, families asked to be informed as the program unfolded.

Concerning formulation of tasks, most participant groups questioned how staff would be assigned to the program. This question seemed to be driven by a perception that staff would be lost to residents not in Namaste Care, only partly assuaged by a reminder that it might be feasible to implement this group program without affecting the staff-to-resident ratio for those not attending program. At site 1, unlicensed staff members were particularly concerned about how 2-person lifts and transfers would be negotiated with one member of the team assigned to work in Namaste Care; at site 2, licensed staff mentioned the same concern on behalf of unlicensed staff members. At site 2, unlicensed staff was particularly concerned about how the program would be negotiated around mealtimes, naptimes, and toileting needs.

Staffing considerations

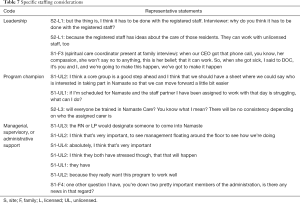

The ecological framework identifies three leadership-related staffing considerations as important to successful implementation. One is effective leadership, including priority-setting, consensus-making, incentives, and general oversight. A second is the presence of program champions—informal leaders who will rally support and negotiate solutions. Finally, implementation is more likely to be successful with the regular involvement and encouragement of senior employees, such as supervisors and managers (Table 7).

Full table

Site 1 staff and family members readily identified the director of nursing care as the person responsible for leading the program. Family members at site 1 expressed concern that two key managerial positions were currently unstaffed. Unlicensed staff recommended forming an implementation working group to assist with guiding the program, and requested that licensed staff offer supervisory support by assigning nursing assistants to work in Namaste Care. They further recommended that managers actively support the program by checking on staff and residents during the first weeks of implementation, by encouraging staff, and by facilitating teamwork.

At site 2, staff readily identified the director of nursing care as the leader. A few licensed staff members recommended consistent program staffing to improve continuity of care. In addition, one licensed staff member thought the program was best led by nurses in cooperation with nursing assistants.

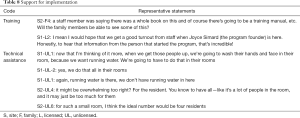

Support for implementation

Adequate training and technical assistance can be vital to the successful implementation of any program. The ecological framework defines technical assistance as a combination of resources offered to providers after implementation begins, including ongoing training, training of new staff, emotional support, and mechanisms for problem-solving. We also considered comments about appropriate space, equipment, and supplies in this category (Table 8). With respect to training, licensed staff at site 1 expressed a need for education, and hoped that all staff would participate. At site 2, advisory council members were aware of a book about Namaste Care and expressed interest in reading it. Concerning the need for space, equipment, and supplies, unlicensed staff at site 2 commented that the room chosen for Namaste Care was too small. Unlicensed staff at site 1 commented that lack of access to water supply in the identified space might be a barrier to implementing some Namaste Care activities.

Full table

Discussion

This study makes an important contribution to an understanding of barriers and enablers to implementing Namaste Care, a program that promotes attention to quality of life in the late stages of dementia and is consistent with a palliative approach to dementia care. In this study, the ecological framework (22) was used to identify a range of factors known to be associated with implementation success, including characteristics associated with the innovation, health providers, and the broader context (the Canadian LTC system), as well as organizational characteristics, including practical supports, capacity for change, work flow considerations, and coordination of leadership among the staff cohort.

As we analyzed interviewee statements related to the Canadian LTC context (e.g., policy, politics, and funding) we noted concerns that some existing governmental and regional policies (e.g., 2-person lifts and transfers for some residents, infection control, and no-scent policies) might be difficult to navigate given some program characteristics. Somewhat similar concerns arose in a multi-facility implementation trial in the UK (e.g., difficulty working around a practice norm of wearing gloves during care) (19). When local policies and resulting practice norms are identified as barriers to implementation, any changes to the practices used to meet policy objectives should be introduced and monitored very carefully during implementation to ensure dual attention to policy goals and intervention fidelity.

Still, participant comments also suggested that Namaste Care is perceived as needed and beneficial, consistent with palliative care and resident-centred care philosophies, and likely to improve outcomes such as a sense of relationship and reduced agitation. These perceptions align well with staff perceptions of Namaste Care in other settings (17,20), and initial reports of outcomes associated with Namaste Care. In particular, the program appears to contribute to a number of positive psychosocial outcomes, including improved quality of life and relationships (15), as well as reductions in the need for psychotropic medications, lower rates of psychiatric symptoms, and improved communication (16). On the basis of early research findings and the response to Namaste Care from LTC staff and families, there may be considerable potential to increase use of Namaste Care in the Canadian LTC system.

Despite liking the program and anticipating benefits, participants were concerned about the resulting demand on resources and an impact on workflow, and suggested more staff would be needed. For example, offering a morning session of Namaste Care was seen as removing resources needed to provide personal care and breakfast. Some were concerned that improving care for some residents would compromise care for others—a concern that has arisen in other LTC studies (32). The workplace dynamics in Canadian LTC homes may offer some explanation for the level of concern that surfaced on this topic. A social network analysis noted that a hierarchical division of labour within LTC teams in Canada results in a very mechanistic approach to work, particularly for nursing assistants (33). Work in Canadian LTC homes has also been described as particularly task-oriented and role-differentiated (34). Nevertheless, resource constraints in LTC are well documented elsewhere (35,36), do appear to create time pressure (23,26,34,37-39), and have operated as a barrier to offering Namaste Care at the recommended intensity in prior studies (20). Indeed, given that similar concerns about LTC workload exist on a global scale, it may be helpful for homes implementing Namaste Care to plan for an additional staff member to cover the part of the day during which Namaste Care is offered. Additional staffing may be especially helpful during the initial implementation period, to facilitate change.

Our interviews with unlicensed staff suggested that both sites were reliant on a casual labour force. This is to be expected, since absenteeism and turnover are persistent problems in LTC (40). However, unlicensed staff also noted that the bulk of their work is coordinated in 2-person teams. They attributed this general practice to a specific requirement to coordinate safe lifts and transfers of many residents by involving two employees, but also noted that this practice facilitates mentorship of casual staff by regular staff. Thus, to unlicensed providers, Namaste Care could be seen as a double threat to a well-established system of work. On this basis, we recommend that homes considering Namaste Care evaluate the stability of their workforce prior to implementation, and engage unlicensed staff actively in the planning process to ensure that these concerns are effectively addressed.

The apparent conflict between perceiving the program as very valuable and being reluctant to accommodate it mirrors other results suggesting that the low resource base and task-oriented nature of work in Canadian LTC settings competes directly with health providers’ interests in forging stronger relationships with the residents (41,42). On one hand, Namaste Care is a solution to this problem, since it is promoted as a way to improve care without necessarily increasing staffing, and since it provides a means of systematizing resident-centred care. On the other hand, the comments of unlicensed providers suggest that Canadian LTC homes may need to carefully consider how staff assignment of duties can be reformulated or whether resources may need to be increased to accommodate Namaste Care.

Nursing assistants also raised the possibility that Namaste Care might provoke stigma and fear of participating for residents or their families. For instance, they anticipated that residents might notice that their peers in Namaste Care die within weeks or months of their initial participation in the program, and come to associate the room with death. Since the program is designed for individuals with late-stage cognitive impairment, whose memory impairment is likely to hinder awareness that people who attend the program ultimately pass away, we think this unlikely. Nevertheless, death anxiety and taboos about discussing death are well documented (43-46), including among North American health providers (47-49). Thus, although conceptualizing Namaste Care as end of life dementia care may help to increase engagement in dedicating resources to the least demanding—and arguably most vulnerable—LTC residents (14,50), this message needs to be delivered carefully, perhaps along with continuing education, in order to avoid creating additional implementation barriers.

A range of specific organizational practices and processes are important to successful program implementation. These include collaboration, shared decision-making, coordination with other organizations, effective communication processes, and shared task formulation. Overall, participant comments about these factors suggested that despite concerns about staffing capacity, staff at both sites were willing to actively participate in the development of communication systems to support Namaste Care, including day-to-day assignment of duties. Family members’ comments also suggested their interest in participating in communication about the program. Although engagement in identifying practices and processes was high, in light of other research on the Canadian LTC system, we do anticipate that some implementation barriers might nevertheless be encountered here. For instance, reorganization of work to support Namaste Care is most likely to affect the roles of unlicensed health providers, yet unlicensed providers are least likely to be included in decision-making processes (34,39). Meaningful family engagement is also recognized as an area needing improvement in many Canadian LTC homes (51). Still, given the level of engagement from staff and family participants, to the extent that engagement in collaborative decision-making about work practices and processes is recognized and acted upon prior to implementation, this should operate as an implementation facilitator, as appears to be the case in some previous Namaste Care trials (20).

We were particularly encouraged to find health providers expressed interest in forming a core group of staff to either plan or staff the program. Since staff planning groups are also known to foster informal leadership (52), engaging staff members with interest in planning for Namaste Care should help to facilitate successful implementation. Some staff members also voiced the importance of managers maintaining a consistent early presence in the program. Beyond an active presence, research suggests that leadership should also include direct expressions of recognition or appreciation and support (53,54). Overall, effort to identify and engage formal and informal leaders is likely to be an important enabler, and prior successful implementations of Namaste Care support this (15,20).

Participants were not very concerned about recruiting practical support for implementation, including training, supplies and technology. In particular, participants were pleased that training would be provided and voiced interest in attending. The only concern voiced about practical support for implementation was related to space. Most Canadian LTC homes are at capacity, and many frail older adults with extensive support needs are on wait lists for placement (55). Without a surplus of space, existing spaces must be shared or repurposed. Both sites were able to repurpose smaller gathering spaces for Namaste Care by moving other activities from underutilised spaces. Overall, the ease with which reasonably suitable spaces for small group programs could be identified and the low reliance of Namaste Care on special technologies and supplies are likely implementation facilitators.

This study had some limitations. First, the ecological framework was not identified a priori, which compromised our ability to more thoroughly assess barriers and enablers to implementation. Secondly, participants’ comments were based on a brief summary of the program, rather than direct exposure to it. It is possible that increasing participants’ exposure to the program (e.g., by having them read about it, watch video footage, visit an existing program, or plan for implementation) might lead to somewhat different results. Further, since the interviews were completed after both sites had committed to implementing Namaste Care, interviewees may have emphasized communication and work planning issues to a greater degree than if the interviews had been coordinated prior to the sites’ commitment. In addition, the predictive value of these results may be limited; for instance, participants were very engaged in the idea of collaborating to launch the program, whereas empirical research demonstrates that collaboration across roles is a weakness of the Canadian LTC system (34). To address these issues, future studies might explore implementation determinants over the course of the first several months of Namaste Care launches.

Conclusions

Namaste Care is an approach to advanced dementia care that has had global impact. Although early results suggest that Namaste Care is a promising model for late-life dementia care, a great deal of research is still needed to ascertain the range of outcomes for residents, the program’s impact on LTC resources, and the conditions under which Namaste Care is most likely to be successfully implemented and effective. By employing the ecological framework (22), we were able to consider a range of determinants already known to be relevant in health contexts, including factors associated with the intervention, health providers, organizational contexts, and health systems. Overall, our results suggest that implementations of Namaste Care in the Canadian LTC system are likely to be enabled by widely shared perceptions that the program is beneficial, needed, and compatible with dominant philosophies of care. On the other hand, a barrier to implementation of Namaste Care in the Canadian LTC system is that interviewees had strong reservations about organizational capacity to accommodate the new program. Thus, support for a high-fidelity implementation across both participating LTC homes was mixed. Our data paint the picture of a well-considered and appealing intervention encountering a health system running near peak efficiency.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by Alzheimer Society of Canada (No. 16-09 to Sharon Kaasalainen).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: Co-author J Simard is an independent consultant who created the Namaste Care program and has promoted it internationally. A potential conflict of interest is inherent in her collaboration with this research team, formed to study the implementation of Namaste Care in Canada. To guard against excessive influence, Ms. Simard has abstained from participation in data collection and analysis. Her involvement on the team helps to maximize intervention fidelity and knowledge of global research on Namaste Care. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (No. 15-092) and University of Saskatchewan Behavioural Research Ethics Board (No. 15-267), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- Frohlich N, De Coster C, Dik N. Estimating Personal Care Home Bed Requirements. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, 2002.

- Hirdes JP, Mitchell L, Maxwell CJ, et al. Beyond the 'iron lungs of gerontology': using evidence to shape the future of nursing homes in Canada. Can J Aging 2011;30:371-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seitz D, Purandare N, Conn D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr 2010;22:1025-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:321-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCarthy M, Addington-Hall J, Altmann D. The experience of dying with Dementia:A retrospective study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;12:404-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Steen JT, Ooms ME, van der Wal G, et al. Pneumonia: The demented patient’s best friend? Discomfort after starting or withholding antibiotic treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1681-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blasi ZV, Hurley AC, Volicer L. End-of-life care in dementia: a review of problems, prospects, and solutions in practice. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2002;3:57-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrison RS, Siu AL. A comparison of pain and its treatment in advanced dementia and cognitively intact patients with hip fracture. J Pain Symptom Manage 2000;19:240-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abbey J, Froggatt KA, Parker D, et al. Palliative care in long-term care: A system in change. Int J Older People Nurs 2006;1:56-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2014;28:197-209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hall S, Kolliakou A, Petkova H, et al. Interventions for improving palliative care for older people living in nursing care homes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011.CD007132. [PubMed]

- Kaasalainen S, Sussman T, Neves P, et al. Strengthening a Palliative Approach in Long-Term Care (SPA-LTC): A New Program to Improve Quality of Living and Dying for Residents and their Family Members. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:B21. [Crossref]

- Sampson EL, Ritchie CW, Lai R, et al. A systematic review of the scientific evidence for the efficacy of a palliative care approach in advanced dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2005;17:31-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simard J, Volicer L. Effects of Namaste Care on residents who do not benefit from usual activities. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2010;25:46-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manzar B, Volicer L. Effects of Namaste Care: Pilot Study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2015;2:24-37.

- Stacpoole M, Hockley J, Thompsell A, et al. The Namaste Care programme can reduce behavioural symptoms in care home residents with advanced dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;30:702-709. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simard J. The End-Of-Life Namaste Care Program for People with Dementia. Second Edition. Baltimore: Health Professionals Press, 2013.

- Simard J. Namaste Care: The End of Life Care Program for People with Dementia, 2016. Available online: http://www.namastecare.com

- Thompsell A, Stackpoole M, Hockley J. Namaste care: the benefits and the challenges. J Dement Care 2014;22:28-30.

- Solman A, Hirst S. Using sensory activities to improve dementia care. Nurs Times 2015;111:12-5.

- Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci 2015;10:53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41:327. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lopez SH. Culture change management in long-term care: A shop-floor view. Polit Soc 2006;34:55-80. [Crossref]

- Luff R, Ellmers T, Eyers I, et al. Time spent in bed at night by care-home residents:Choice or compromise? Ageing Soc 2011;31:1229-50. [Crossref]

- Morgan DG, Crossley MF, Stewart NJ, et al. Taking the hit: Focusing on caregiver “error” masks organizational-level risk factors for nursing aide assault. Qual Health Res 2008;18:334-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bowers BJ, Esmond S, Jacobson N. The relationship between staffing and quality in long-term care facilities: Exploring the views of nurse aides. J Nurs Care Qual 2000;14:55-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2335-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Using codes and code manuals: A template organizing style of interpretation. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL. editors. Doing Qualitative Research. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1999;163-78.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis, 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1994.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004;24:105-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cammer A, Morgan D, Stewart N, et al. The hidden complexity of long-term care:How context mediates knowledge translation and use of best practices. Gerontologist 2014;54:1013-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cott C. We decide, you carry it out: A social network analysis of multidisciplinary long-term care teams. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1411-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Daly T, Szebehely M. Unheard voices, unmapped terrain: Care work in long-term residential care for older people in Canada and Sweden. Int J Soc Welf 2012;21:139-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knopp-Sihota JA, Niehaus L, Squires JE, et al. Factors associated with rushed and missed resident care in western Canadian nursing homes: A cross-sectional survey of health care aides. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:2815-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mallidou AA, Cummings GG, Schalm C, et al. Health care aides’ use of time in a residential long-term care unit: A time and motion study. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:1229-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dellefield ME, Harrington C, Kelly A. Observing how RNs use clinical time in a nursing home: A pilot study. Geriatr Nurs 2012;33:256-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qian SY, Yu P, Zhang ZY, et al. The work pattern of personal care workers in two Australian nursing homes: a time-motion study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:305. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ribbe MW, Ljunggren G, Steel K, et al. Nursing homes in 10 nations: A comparison between countries and settings. Age Ageing 1997;26:3-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh DA. Effective Management of Long-Term Care Facilities. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2014.

- Banerjee A, Armstrong P, Daly T, et al. Careworkers don't have a voice: Epistemological violence in residential care for older people. J Aging Stud 2015;33:28-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hunter PV, Hadjistavropoulos T, Kaasalainen S. A qualitative study of nursing assistants' awareness of person-centered approached to dementia care. Ageing Soc 2015;36:1211-37. [Crossref]

- Venne R, Goodridge D, Quinlan E, et al. Let’s talk about dying: Proposals for encouraging discussion of advance-care planning. Int J Aging Soc 2015;5:33-46. [Crossref]

- Goodridge D, Quinlan E, Venne R, et al. Planning for serious illness by the general public: a population-based survey. ISRN Family Med 2013;2013:483673. [Crossref]

- Beck ER, McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, et al. Health care professionals' perspectives of advance care planning for people with dementia living in long-term care settings: A narrative review of the literature. Dementia (London) 2017;16:486-512. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharp T, Moran E, Kuhn I, et al. Do the elderly have a voice? Advanced care planning discussions with frail and older individuals: a systematic literature reviews and narrative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e657-e668. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nia HS, Lehto RH, Ebadi A, et al. Death Anxiety among Nurses and Health Care Professionals: A Review Article. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 2016;4:2-10. [PubMed]

- Marcella J, Kelley ML. Death is part of the job in long-term care homes. SAGE Open 2015.1-15.

- Peterson J, Johnson M, Halvorsen B, et al. What is it so stressful about caring for a dying patient? A qualitative study of nurses' experiences. Int J Palliat Nurs 2010;16:181-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simard J. Silent and invisible; Nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Nutr Health Aging 2007;11:484-8. [PubMed]

- Dupuis S, McAiney C, Fortune D, et al. Theoretical foundations guiding culture change: The work of the Partners in Dementia Care Alliance. Dementia (London) 2016;15:85-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Downey M, Parslow S, Smart M. The hidden treasure in nursing leadership: Informal leaders. J Nurs Manag 2011;19:517-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hollinger-Smith L, Ortigara A. Changing Culture: Creating a Long-Term Impact for a Quality Long-Term Care Workforce. Alzheimers Care Today 2004;5:60-70.

- Scott-Cawiezell J, Main DS, Vojir CP, et al. Linking nursing home working conditions to organizational performance. Health Care Manage Rev 2005;30:372-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams AP, Challis D, Deber R, et al. Balancing institutional and community-based care: Why some older persons can age successfully at home while others require residential long-term care. Healthc Q 2009;12:95-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]