Introducing Namaste Care to the hospital environment: a pilot study

Introduction

The rising prevalence of dementia is impacting on acute hospitals and placing increased expectations on health and social care professionals to improve the support and services they are delivering (1-5). Concerns have been raised about quality of symptom management, the provision of person-centred care, the support received by families/loved ones and care at the end of life of people with dementia (6-13).

It has been recommended that good practice in dementia care relies on adopting a palliative approach to care and meeting people’s physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs (1,13-15). However, despite being the leading cause of death in England and Wales, dementia is still not freely recognized as a terminal illness meaning access to palliative care services is difficult (16).

Carers for people with dementia who had died in a hospital were more likely to report care as poor compared to those without a dementia diagnosis (10). For many, the idea of a good death involves being in an environment that is familiar with close family/friends; being free of symptoms; receiving care that is individualised (17). Following reports highlighting poor, undignified treatment to those who died in hospital with dementia it has been identified that the culture of care in hospitals needs improvement (11,18).

Increased dementia training for staff that includes initiatives that promote dignity; enhancing communication skills and recognizing that a person with dementia may be approaching the end of their lives are needed (19).

Spiritual care is defined as recognition and response to the needs of the human spirit when in times of trauma, ill health or sadness (20). The spiritual needs of people with advanced dementia tend to be ignored in all care settings, including hospitals (19,21-25). Person centred care aims to support and maintain the person’s sense of self and self-worth and recognizes the fundamental needs of people with dementia, such as the need for attachment, identity, occupation, social interaction, comfort and inclusion (26-28).

The majority of activities developed in dementia care settings are aimed at people with mild to moderate dementia, who can still communicate verbally and engage in group activities, with little development in services for those in the later stages of the disease (29-31). Multisensory programmes have been developed to help people with advanced dementia feel a sense of connection with themselves and others (32,33).

Namaste Care is a multisensory programme specifically developed for people with advanced dementia, developed in the USA by geriatric consultant Joyce Simard. The term ‘Namaste‘ is an Indian greeting which means ‘to honor the spirit within’. Namaste Care is designed to reach those who are socially withdrawn and no longer able to benefit from social and group activities, have severe cognitive impairment, spend a lot of time sleeping, have limited verbal abilities and require care with all activities of living (31). The programme integrates meaningful activity and multisensory stimulation (such as massage and aromatherapy, touch, music, color, tastes and scents), with nursing care, person-centred care and reminiscence and provides carers with education and family/loved ones with support (see Box 1) (31).

Full table

Namaste Care has been implemented in care homes and some hospices in the USA, Canada, Australia and parts of Europe. Evidence is starting to emerge in relation to its benefits, including improvements in social interaction, communication and nutritional intake, increased interest in the surrounding environment, decreased indicators of delirium, and a reduction in agitated behaviors and the need for anti-anxiety medications (34-38). In addition, one of the benefits in terms of service provision is that the programme requires no extra staff or expensive equipment (35).

Namaste Care has recently been implemented at the Health and Aging Unit (HAU) of an inner-city teaching hospital. It is a new addition to the hospital’s dementia services and was introduced to try and improve the quality of life of people with advanced dementia being cared for in the hospital. This is the first implementation of the Namaste Care programme in an acute hospital settling. As Namaste Care is a new service to the acute sector, no research is available regarding the effects of its implementation in this particular area.

Aim and objectives

The aim of the research was to explore whether Namaste Care is an appropriate service within an acute hospital setting. Its objectives were to explore: staff perceptions of the challenges in caring for patients with advanced dementia; staff awareness and understanding of Namaste Care; whether staff members felt (and in what ways) Namaste Care has helped them to care better for patients living with advanced dementia; and if staff felt patients’ symptoms were better controlled (and in what ways) after implementation of Namaste Care.

Methods

Study setting and intervention

The study is based between three elderly care wards (HAU) at a large inner-city teaching hospital. The unit’s day room has been developed into a sensory room, which features blackout blinds, mood lighting, a multi-media system for both music and nature videos and aromatherapy diffusers. This area provides the setting for the group activities associated with Namaste Care. Before introduction of Namaste Care, Professor Joyce Simard delivered teaching sessions to staff at the hospital, which provided information about dementia, Namaste Care and practical planning for development of the Namaste Care within the institution.

Patients with advanced dementia were identified by the occupational therapy team and referred to the activity coordinators, who provide Namaste Care. Namaste Care is provided either as a group or one-to-one session, depending on patients’ level of need. Group sessions involve no more than six patients. During the session the room is dimly lit, scented with lavender and relaxing music appropriate and appreciated by the patient group is played.

The focus of care is to create relaxing, enjoyable and stimulating experiences. Group sessions usually last 1 h, with single sessions lasting between 20 and 30 minutes. The content of the session varies, depending on individual patients’ likes, wants and ability. All patients are greeted with loving touch. Generally, session contents include hand and foot massage, reminiscence, singing familiar songs and pampering such as combing and styling of hair, painting patients’ nails or providing a wet shave for men. For those nursed in bed, music equipment, lotions and reminiscence equipment is taken to the bedside and used in the same way as during group sessions. There is no set structure to the amount of Namaste Care sessions a person receives. However, most patients are seen three times per week, during either group sessions or on a one-to-one basis. There is not an individual Namaste Care budget within the unit so all Namaste Care is provided using current or donated equipment. Feedback from each session is recorded using the electronic patient records system.

As the service is led by activity coordinators, not health professionals, families/loved ones do not benefit from formal family meetings where discussions take place about the patient’s current health status, likely disease trajectory and future care priorities. Such meetings are considered an important aspect of Namaste Care (31). However, ward staff are encouraged to liaise with families to inform and educate them about Namaste Care and to encourage them to bring in patients’ personal items for reminiscence.

Study participants

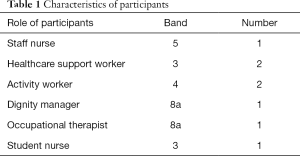

The inclusion criteria were nursing staff, healthcare support workers, doctors, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and activity staff working in the HAU. Exclusion criteria were ward porters, kitchen staff, and staff not working on HAU (Table 1).

Full table

Recruitment

Potential participants were approached by a person independent of the research (nominated clinician) and were provided with an information sheet explaining what participation in the study would involve and requesting their voluntary consent to be interviewed. After a minimum of 24 h in which to consider, the independent party gained informed written consent from interested parties.

Eight participants were recruited to the study. The participants included trained and untrained nursing staff, an occupational therapist, a dignity manager and activity workers.

Data collection

In view of the lack of evidence regarding the feasibility of in Namaste Care within an acute hospital setting, and the intention to explore the effectiveness of a new service through staff experience, an exploratory qualitative interview study design was adopted using semi-structured, face-to-face interviews (39,40). The interview format comprised a series of open-ended questions based on specific topic areas (Box 2). The interviews took place on HAU. Interview data were collected over a 2-week period using a digital recording device. Notes were taken during the interviews with regard to the interviewees’ body language and general attitude during the process.

Full table

Analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author and then read and re-read so that she became familiar with the data. The transcripts were then analysed using the framework approach (41). Framework analysis provides a linear and systematic process to qualitative analysis and is deemed suitable for policy research that asks specific questions, has a limited time frame and a pre-designed sample (42). In the analysis, a hierarchical thematic framework was developed to organize/classify data according to key themes, which were then subdivided into related subthemes. This was an iterative process in that the transcripts were constantly re-read to ensure that the themes were firmly based on the raw data. Throughout the process, further themes emerged and some themes were re-categorised. Any unusual views were noted and the data further explored for potential reasons for such views. Each main theme was then charted by completing a table containing the theme, its related subthemes and definition summaries. The charts enabled differences, patterns and connections between the categories to be explored (41,42).

Ethical considerations

The research project was planned with the aim of minimising distress and inconvenience to both participants and patients. Informed and voluntary consent was sought from participants, who were able to withdraw from involvement within the research project at any time and all potential participants were able to decline involvement without prejudice (43). Anonymity and confidentiality of participants were maintained throughout all stages of the research process and the collection and storage of research data adhered to the Data Protection Act 1998. If became distressed when discussing the interview questions, emotional support was available to participants, this was not required during the study.

Permission to conduct the research was sought and gained from relevant senior clinicians within the Trust and the Deputy Director of Nursing, and full ethical approval granted.

Results

Two main themes, with associated subthemes, emerged from the analysis. The main themes were: difficulties establishing therapeutic relationships with patients with dementia in hospital; and the benefits of Namaste Care in an acute hospital setting. In reporting the results, excerpts taken from a wide range of participants have been used to illustrate the themes and are denoted by sample number and participant role.

Difficulties establishing relationships with patients with dementia in hospital

Lack of time and resources

The participants all stated that caring effectively for people with advanced dementia takes time and requires an adequate number of staff on the wards.

“With um various dementia symptoms, the confusion, the agitation, umm, in patients can be very difficult to deal with Everything is always very time consuming And well that needs to be allowed for because I mean the practicalities and reality of it is that we haven’t got the staffing for it. I mean the ward is short staffed Even when we are fully staffed it’s asking a lot to be able to spend enough time to calm a patient down enough to be changed” (002/01 Staff Nurse).

Participants wanted to provide the best care for their patients yet experienced difficulties in managing individual patient need in balance of the needs of the ward as a whole. Patients with advanced dementia were reported to have varying levels of physical ability. Those who were more physically dependent required regular hoisting and repositioning, which placed a large physical burden on the staff caring for them. The level of patient dependency left staff members feeling physically and mentally drained. Non-ambulant patients were unable to transfer to the sensory room for group sessions as activity workers were not trained to transfer patients using a hoist and ward nurses were frequently too busy to take patients to the sensory room. Participants felt limited by the amount of resources available to be able to engage with patients in holistic activities such as aromatherapy and massage.

“It can be very sad sometimes to see the patients, because they are not engaging, they are not stimulated, even if they are in a bay. There’s nurses and healthcare assistants, plenty of people coming in and out of the bay. They’ve got other patients around them but they’re just sat in the corner. They’re not engaging, they’re not stimulated...Umm, that can be very difficult” (002/01 Staff Nurse).

Lack of time and the minimal resources available led to participants feeling helpless when trying to provide care to this patient group. It was felt that if there were more staff, the level of care provided to patients with advanced dementia would improve, as more time could be spent caring for, communicating with and stimulating them, gaining better insight into their needs, as well as caring for them physically.

Lack of confidence leading to fear and anxiety

Caring for patients with agitation caused anxiety and fear in participants. Participants lacked confidence in how best to manage such behaviors, together with fear that they would exacerbate this and concerns about their own safety.

“There was a particular patient, patient X that I will call He was wandering, very high risk of falls, very high risk of absconding. Umm, very aggressive, quite a large man and people used to hold him at arm’s length” (005/02 Healthcare Support Worker).

“I think it’s the fear from staff has been one of my challenges. You know, just how to interact with different people” (006/01 Dignity Manager).

Staff appeared to find it difficult to care for those who were unable to express their preferences/wishes, creating a fear of providing inadequate care.

“Knowing what to do can be quite frightening too, because people can’t communicate their wishes” (006/01 Dignity Manager).

Nurse participants expressed difficulty in assisting patients with basic tasks such as eating and drinking, administering medication and providing proper symptom assessment. Activity staff felt that because patients could not state clearly what they wanted, they could not plan general individual or group activity sessions efficiently as they did not know whether particular activities would be to a person’s taste, or would cause psychological distress to the patient.

The benefits of Namaste Care in an acute hospital setting

A reduction in agitated behavior

All participants felt that Namaste Care had a positive effect on the agitated behavior.

“Their body language seemed more relaxed, they are less agitated” (003/02 Activity Worker).

“I found out that he loved church music. He used to like going to church. So, on my telephone I’ve got, umm, hymns. I used to play him hymns and it calmed him completely. It took him back to a place where he was happier, content” (005/02 Healthcare Support Worker).

Patients were observed to be more relaxed and calm. For example, the Staff Nurse (002/01) described a male patient had been agitated and wandered the ward, often trying to get into other patients’ beds. Following a group Namaste Care session where he received a wet shave and was moisturized with his own products, he was observed to be more alert, talkative and appeared confident.

Participants began to read agitation and distressed behaviors as a means of communication for people with advanced dementia with limited verbal skills. When Namaste Care was observed not to be alleviating distress and agitation, staff would look for reasons why this was the case.

“Sometimes Namaste doesn’t work and I think that’s really good because it shows that there’s something else going on like the patients in pain or has a wet pad. I think it helps us in finding out what’s going on with the patient when they can’t really tell you” (006/01 Healthcare Support Worker).

Connecting and communicating with patients with dementia using the senses

Namaste Care was perceived to be different from usual activities for people with advanced dementia as its central tenet was sensory stimulation. For example, touch was observed by participants to be a powerful means of communicating and connecting with patients with advanced dementia.

“There’s something about touching the skin. You are connecting with that person. I find it very soothing especially if you have a patient that’s very agitated” (005/02 Healthcare Support Worker).

“I think it’s a way of actually connecting with that patient” (005/02 Staff Nurse).

The perception of the Dignity Manager (006/01) was that infection control guidelines within the acute hospital setting had made staff reluctant to actually touch patients’ skin. The approach adopted by Namaste Care gave staff confidence and permission to touch patients and be tactile with them.

Participants found that the use of sensory activities resulted in patients displaying an increased interest in their surroundings, becoming more alert and confident. This enhanced communication which helped to establish therapeutic relationships between staff and patients.

A way of showing people with dementia they are cared for and valued

“It helps patients feel, that they are listened to, and their needs are still met you know the communication side that you get from Namaste because just sitting there and shaving someone who can’t do it, sitting there and just putting facial cream on someone’s face who used to that and they haven’t done that in ages makes a big difference makes them feel a sense of beauty again” (003/01 Activity Worker).

The multi-sensory stimulation techniques associated with Namaste Care gave staff the opportunity to reach out to patients with advanced dementia, stimulate them, engage with them in a way they had not done previously, promote a sense of social inclusion and create relaxing, comforting, reassuring and enjoyable experiences. These factors were deemed to improve patients’ quality of life while in hospital.

“They don’t get talked to and then have the time to express anything they could be able to sort of express. So this service actually provides that to patients, and it’s actually sort of more about that smile as well because, that you actually need to provide for patients whereby you know, they actually sort of feel there is someone, you know, the contact, you know the listening to music. That calmness, that actual calmness of this is really sort of benefit, more effective to the patient” (004/01 Head of Occupational Therapy).

All participants perceived that Namaste Care had aided them in better caring for patients with advanced dementia. Namaste Care gave new ideas for meaningful activity, communication, calming techniques and for enriching quality of life. Participants responded with emotion when describing their experiences delivering care.

“I just brushed her hair, she shut her eyes. I just thought, you know, this is lovely I don’t deserve this I think I’ve seen first-hand something positive” (006/01 Dignity Manager).

It was felt that Namaste Care was easy to set up and maintain in acute hospitals due to the flexible nature of the sessions, which can be carried out on an individual basis by the bedside or within a group. All participants felt positive towards Namaste Care, feeling that it truly focused on and delivered care specific to the needs of those with advanced dementia and was a true demonstration of quality care.

Discussion

Communication difficulties were cited as a barrier to identifying patients’ needs and forging connections with patients. Behavioral symptoms, for example, agitation and aggression, resulted in staff feeling anxious and fearful in relation to caring for people with dementia.

There is growing is evidence that hospital staff, including nurses, do not feel that their training is sufficient to enable them to care effectively for people with dementia, which leads to them finding looking after people with dementia challenging (1,6-9,18,19,44). Behavioral symptoms are common in older people with dementia admitted to acute hospital (3,23,24,44). In their longitudinal cohort study of 230 people with dementia, aged over 70 years, who were admitted to two acute hospitals in London as a result of acute medical illness, found that the most common behavioral and psychiatric symptoms were aggression, activity disturbance, sleep disturbance and anxiety.

Participants felt the hospital environment was not conducive to the provision of good dementia care due to its hectic and noisy attributes and the lack of services to meet the needs of people with more advanced dementia. In addition, there was limited time to care effectively for this client group. Patients who were agitated and wandered around the ward required a great deal of attention and time, which was a major strain on staff. These findings are present in national literature relating to dementia care in hospitals (7).

Family carers of people with dementia who are admitted to hospital perceive that being in hospital exacerbates confusion, agitation, distress and difficulties with communication as a result of the lack of opportunity for social interaction and hospital staff’s limited understanding of dementia (18). Providing care that was not felt to meet the needs of people with advanced dementia created an emotional burden and feelings among the participants.

Namaste Care appeared to enhance the care of people with advanced dementia in the hospital settling. It was perceived to enrich the lives of patients by providing stimulation, comfort and relaxed experiences. Participants felt that Namaste Care increased social interaction and enhanced communication. This improved the participants’ sense of connection with patients and their ability to care with compassion. Namaste Care was, therefore, considered to provide pleasure to both the staff delivering the care as well as the patients receiving it.

Similar perceptions can be found in research into the benefits of Namaste Care within care homes (34-38,45,46). For people with advanced dementia who are withdrawn and have reduced social interaction, involvement in Namaste Care can lead to improved communication and interactions with their carers and increased interest in the surrounding environment (37,38). The introduction of Namaste Care in a care home has also been found to result in care home staff becoming less task-orientated, more patient-centred and better able to assess patients’ conditions (45).

An action research study was conducted by St Christopher’s Hospice, London, in five UK care homes, to establish whether Namaste Care can enrich the quality of life of care home residents, families and staff without requiring additional resources. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected from residents with advanced dementia, care staff, managers and relatives, before, during and after introduction of the programme (34,35). Analysis of the qualitative data revealed that residents were perceived to enjoy being involved in Namaste Care, were more alert and responsive and engaged more actively with others. Residents also appeared more relaxed and less agitated. The care home staff felt that Namaste Care helped them connect and communicate with residents, meet their human needs, gave them permission to provide more intuitive care, encouraged them to be creative in developing the programme for individual residents and assisted them in fostering easier, closer relationships with relatives. Overall, staff found that Namaste Care was rewarding, and increased their confidence and self-esteem (35,36).

Participants in the current study observed that Namaste Care calmed and relaxed patients and reduced levels of agitation. A reduction in agitated behavior is a common theme within Namaste Care research (37,38,46). The quantitative aspect of the St Christopher’s Hospice study used the neuropsychiatric inventory-nursing homes (NPI-NH) and Doloplus-2 behavioral pain assessment scale for the elderly to collect data from the 37 residents included in the research. Analysis found that the severity of behavioral symptoms, pain and occupational disruptiveness decreased over time in four of the five care homes included in the study after initiation of Namaste Care. It has also been found that following enrolment in Namaste Care programmes, delirium indicators and the administration of anti-anxiety, anti-psychotic and hypnotic medications among residents decreases and residents sleep less during the day (38,46).

Researchers have concluded that the training in symptom assessment that staff members receive before implementation of Namaste Care may be one of the reasons for a reduction in agitated behavior (46). It has also been suggested that the provision of soothing, individualised, person-centred care and activities, the calm atmosphere and approach to care, regular, structured, one-to-one time with a care worker, the opportunity to communicate and express emotion and therapeutic touch and may be other causes for reduction in agitated behavior (34,35,46). Improved symptom assessment was also cited as a benefit of Namaste Care in the current study as if a patient involved in the programme continued to be distressed or agitated, staff would assess the patient to see whether another problem, such as undiagnosed pain, was present. Therefore, Namaste Care facilitated a more thorough and holistic assessment of the symptoms of patients who were unable to verbalise clearly their care needs.

One participant commented on the restrictions in terms of rules and regulations within the NHS, which left some staff members feeling reticent about using a tactile approach while caring for people with dementia. However, the participant felt that Namaste Care had given staff the reassurance and confidence to be able to touch a patient in a caring way, to which the participants’ response was emotional and moving. Loving touch was seen as a means of increasing staff’s confidence and enabling them to connect with patients. This is supported a mixed-methods study in three residential care facilities in NSW, Australia, to explore the mental health benefits of touch for people with advanced dementia using the Namaste Care programme’s ‘high-touch’ technique (47). The physical act of touch appeared to result in an emotional response from residents, who would become aware of the presence of the person touching them and in turn would reach out to touch them, for example, their hands, face or body. Touch appeared to reignite dormant emotions within the person with dementia and led to social connections, relationships and rapport between the people with dementia and carers and family members. This gave caregivers a greater sense of satisfaction in their caring role. The researchers concluded that people need physical touch in order to feel connected (47).

Although the study participants did not use terms such as ‘spirituality’ and ‘spiritual care’, their descriptions of Namaste Care indicate that the programme fulfils many of the components of what is generally perceived to be spiritual caregiving in relation to people with dementia (see Box 1). Therefore, introduction of the programme into an acute hospital setting may have the potential to help hospital staff meet the spiritual care needs of patients with advanced dementia.

Clinical recommendations

In this study, Namaste Care was led by the activity coordinators, which meant that the components of advance care planning and counselling for families were lost. A key recommendation for improved provision of the Namaste Care service is for it to be delivered by the team as a whole, including nurses and the medical team.

Although the Namaste Care service provided by the hospital was considered by participants to be beneficial, the programme had no clear structure. Generally, patients received Namaste Care three times per week, which is substantially different from the proposed 4 h per day proposed in the original programme (31). There needs to be a more specific plan in place for those receiving Namaste Care in order to better understand the needs and benefits associated with the varying frequency of Namaste Care.

In order for Namaste Care to be fully effective, and to improve the quality of life for people with dementia, it requires strong leadership, adequate staffing and good nursing and medical care (34,35).

Whatever the potential benefits of the Namaste Care programme, it is not a substitute for good clinical care (35). Staff caring for people with dementia in the acute hospital environment, require training in dementia care and support from specialist services (1,3,6). It has also been recommended that within the acute hospital setting there needs to be greater involvement of family carers, more person-centred care planning, strategies to respond to life history, more activity/therapies on the ward, use of volunteers to provide additional support and closer links with palliative care (1,7).

Recommendations for research

As preliminary data, this study indicates that there may be potential benefits of having Namaste Care as an established, hospital service. However, more in-depth, reliable and robust understanding into the benefits of Namaste Care as a hospital programme needs to be ascertained. Namaste Care (a complex intervention) could be explored within mixed-methods research (including a randomised clinical trial) to provide high-quality data in relation to the implications for implementing Namaste Care as a hospital service. A variety of research techniques, e.g., both quantitative and qualitative, should be used in order to ensure research rigour and reliability (48).

Although it has been found that, extra staff and financial resources are not required to implement the programme within care homes (34), whether this is also true of the acute hospital settings needs to be investigated.

Limitations

This exploratory study has a number of methodological limitations.

This study used purposive sampling, that is, staff working on one dementia unit in one acute hospital where Namaste Care had been introduced. This was because the information could only be acquired from a specific clinical area in which the care programme had been implemented. Inclusion within this study was open to all members of the multidisciplinary team working on the unit to allow as much variation as possible within the results.

Only one researcher collected, transcribed and analysed the data, and therefore the analysis was open to researcher bias. To combat this it was important to appreciate the concept of reflexivity, that is, understanding the researcher’s place in the research (49). As a healthcare worker, the researcher had experience of the positive effects of Namaste Care in care homes and hospices. Therefore, it was important for her to recognize her role as a researcher and not a clinician, keeping any pre-conceptions separate to the data gathered. However, unintentionally, this may have affected the way the data was analysed.

The sample was small, with only eight members of staff agreeing to participate in the study. It is possible that the eight participants were those with a genuine interest in the Namaste Care programme and that those who chose not to participate were more ambivalent about the programme or found it unsatisfactory. Therefore, the findings may not be representative of all members of staff with experience of the Namaste Care programme in the hospital’s HAU (50).

The study explored the potential benefits of Namaste Care and not whether staff had any issues or discrepancies with the service. This may have restricted participants in that they were only directly asked to discuss how they felt this service had helped them and not if it, in any way, disturbed their usual work. In addition, the study did not address the depth and scale of improvement felt by the participants. For example, it is not known if the effects were seen only within the Namaste Care session or if the benefits lasted over a longer period.

Conclusions

The services provided in acute hospitals for people with dementia require improvement (1-5). Hospitals need to develop initiatives that promote dignity (19). Hospital staff lack training in how best to care for people with dementia, including communication strategies and the management of behavioral symptoms (18,19). Carers of people with dementia in hospitals continue to report incidences of poor care (18). Namaste Care has been successfully implemented in care homes in varying locations all over the world but never in an acute setting. Namaste Care was well received by the study participants, who felt that Namaste Care served as a tool in providing effective communication with patients with advanced dementia, which helped them to connect with the person through the activities used within. It was also considered to improve wellbeing and reduce agitation, with patients appearing more calm and relaxed afterwards. Namaste Care appeared to provide some answers to the challenges faced by healthcare workers caring for people with advanced dementia, including caring with dignity and enhancing symptom assessment. The results of this small-scale research indicate that the Namaste Care may be an appropriate service to implement within acute hospitals and has the potential to benefit people with more advanced dementia being cared for in acute hospital settings and the staff who care for them.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joyce Simard for her support in training care staff and assistance in adapting the Namaste Care for use in a hospital environment; Min Stacpoole and Ladislav Volicer for sharing their learning and inspiring this study.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by committee/ethics board of King’s College London (No. BDM/12/13-117) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Dementia: Supporting People with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care. NICE Guidelines CG42. London: NICE, 2006.

- Sampson EL, Blanchard MR, Jones L, et al. Dementia in the acute hospital: prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195:61-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sampson EL, White N, Leurent B, et al. Behavioural and psychiatric symptoms in people with dementia admitted to the acute hospital: prospective cohort study. Br J Psychiatry 2014;205:189-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ham C, Dixon A, Brooke B. Transforming the Delivery of Health and Social Care: The Case for Fundamental Change. London: The King’s Fund, 2012.

- Department of Health. Dementia: a State of the Nation Report on Dementia Care and Support in England. London: DH, 2013.

- Alzheimer’s Society. Caring for People with Dementia on Hospital Wards. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2013.

- Royal College of Nursing. Dignity in Dementia: Transforming General Hospital Care. London: RCN, 2011.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. Report of the National Audit of Dementia Care in General Hospitals 2011. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2011.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. National Audit of Dementia Care in General Hospitals 2012-13. Second Round Audit Report and Update. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2013.

- Department of Health. First National VOICES Survey of Bereaved People: Key Findings. London: DH, 2012.

- The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Enquiry. Chaired by Robert Francis QC. London: The Stationery Office, 2013.

- Royal College of Physicians, Marie Curie Cancer Care. National Care of the Dying Audit for Hospitals, England. National Report. London: Royal College of Physicians, Marie Curie Cancer Care, 2014.

- Merel SE, DeMers S, Vig E. Palliative care in advanced dementia. Clin Geriatr Med 2014;30:469-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson A, Eccleston C, Annear M, et al. Who knows, who cares? Dementia knowledge among nurses, care workers, and family members of people living with dementia. J Palliat Care 2014;30:158-65. [PubMed]

- Volicer L, Simard J. Palliative care and quality of life for people with dementia: medical and psychosocial interventions. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27:1623-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’ Society. Marie Curie Cancer Care. Living and dying well with dementia in England: Barriers to care. London: Alzheimer’ Society 2014.

- Department of Health. End of life care strategy. London: DH, 2008.

- Alzheimer’s Society. Fix dementia care: Hospitals. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2016.

- Alzheimer’s Society. My life until the end: Dying well with dementia. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2012.

- NHS Scotland. Spiritual care matters: An introductory resource for all NHS Scotland staff. Edinburgh: UK, 2009.

- Volicer L. End-of-life Care for People with Dementia in Residential Care Settings. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association, 2005.

- Volicer L. Goals of care in advanced dementia: quality of life, dignity and comfort. J Nutr Health Aging 2007;11:481. [PubMed]

- Sampson EL. Palliative care for people with dementia. Br Med Bull 2010;96:159-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Steen JT, Gijsberts MJ, Hertogh CM, et al. Predictors of spiritual care provision for patients with dementia at the end of life as perceived by physicians: a prospective study. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitwood T. Person and process in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1993;8:541-5. [Crossref]

- Sabat SR. The Experience of Alzheimer’s Disease—Life Through a Tangled Veil. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2001.

- Sabat SR. Maintaining the self in dementia. In: Supportive Care for the Person with Dementia. JC Hughes, M Lloyd-Williams, GA Sachs. editors. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010:227-34.

- Lipe AW. Beyond therapy: music, spirituality, and health in human experience: a review of literature. J Music Ther 2002;39:209-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mackinlay E, Trevitt C. Living in aged care: using spiritual reminiscence to enhance meaning in life for those with dementia. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2010;19:394-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simard J. The End-of-Life Namaste Care™ Program for People with Dementia. 2nd. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press, 2013.

- Staal JA, Sacks A, Matheis R, et al. The effects of Snoezelen (multi-sensory behavior therapy) and psychiatric care on agitation, apathy, and activities of daily living in dementia patients on a short term geriatric psychiatric inpatient unit. Int J Psychiatry Med 2007;37:357-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bauer M, Rayner JA, Koch S, et al. The use of multi-sensory interventions to manage dementia-related behaviours in the residential aged care setting: a survey of one Australian state. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:3061-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole M, Thompsell A. OA25 The namaste care programme can enrich quality of life for people with advanced dementia and those who care for them without additional resources. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5 Suppl 1:A8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole M, Hockley J, Thompsell A, et al. The Namaste Care programme can reduce behavioural symptoms in care home residents with advanced dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;30:702-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole M, Thompsell A, Hockley J, et al. Implementing the Namaste Care Programme for People with Advanced Dementia at the End of Their Lives: an Action Research Study in Six Care Homes with Nursing. London: St Christopher’s Hospice, 2013.

- Simard J. Silent and invisible; nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Nutr Health Aging 2007;11:484-8. [PubMed]

- Simard J, Volicer L. Effects of Namaste Care on residents who do not benefit from usual activities. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2010;25:46-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holloway I. Qualitative Research in Health Care. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press, McGraw Hill Education, 2005.

- Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative Research in Health Care. 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

- Ritchie J, Lewis J, Elam G. Designing and selecting samples. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. J Ritchie, J Lewis. editors. London: Sage, 2003:77-108.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koffman J, Stone K, Murtagh FEM. Ethics in palliative care research. In: Textbook of Palliative Medicine. E Bruera, IJ Higginson, C Ripamonti, et al. editors. 2nd edn. London: Hodder Arnold, 2015:211-20.

- O'Shea E, Timmons S, Kennelly S, et al. Symptom Assessment for a Palliative Care Approach in People With Dementia Admitted to Acute Hospitals: Results From a National Audit. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2015;28:255-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trueland J. Soothing the senses. Nurs Stand 2012;26:20-2. [PubMed]

- Fullarton J, Volicer L. Reductions of antipsychotic and hypnotic medications in Namaste Care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:708-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nicholls D, Chang E, Johnson A, et al. Touch, the essence of caring for people with end-stage dementia: a mental health perspective in Namaste Care. Aging Ment Health 2013;17:571-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Medical Research Council. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: New Guidance. London: Medical Research Council, 2013.

- Symon G, Cassell C. Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges. London: Sage, 2012.

- Patel MX, Doku V, Tennakoon L. Challenges in recruitment of research participants. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2003;9:229-38. [Crossref]