Implementation issues relevant to outpatient neurology palliative care

Introduction

It has been 20 years since the Ethics and Humanities Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology issued a statement regarding the need for “neurologists to understand, and learn to apply, the principles of palliative medicine” (1). Since that time other European bodies have set more detailed agendas for the field (2-4) and a great deal of work has been done on a range of topics relating to palliative care and neurologic disease including the development of specialty palliative care clinics for a subset of neurologic conditions including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s disease (PD), neurooncological conditions, and multiple sclerosis (MS) (2,5-8). A growing interest in palliative care training among neurologists is also evident (9). In 2006, Hospice and Palliative Medicine was recognized by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology as a subspecialty with a qualifying examination and there are a growing number of neurologists in the U.S. and elsewhere board-certified in palliative medicine (10). The settings in which these palliative care specialists practice is variable, and many work in hospice or on inpatient consult services. However, there is increasing recognition that outpatient programs are essential to meet the palliative care needs of patients and families affected by neurologic disorders and a growing number of institutions have initiated or are planning outpatient clinics to meet these needs.

Palliative care needs of patients and families affected by neurologic illnesses that can and should be addressed in an outpatient setting include discussing goals of care, caregiver support, spiritual wellbeing, complex symptom management, working with difficult emotions such as guilt and grief, and referral to hospice. There are significant gaps in the care of patients with neurologic illness in these domains (9). While some of these needs may be met through efforts to improve primary palliative care provided by neurologists and other clinicians who care for these patients, the development of specialist palliative care services to handle more complex situations or advanced patients is essential (11,12). There is growing evidence from both neurologic and non-neurologic populations for the potential of outpatient palliative care to improve patient and caregiver outcomes as well as to lower overall healthcare costs, with several additional randomized controlled trials in neurologic patients underway (e.g., OPTCare Neuro, NCT02533921, NCT03076671) (8,13).

Based on these considerations and models of providing palliative care for other chronic conditions, we initiated a team-based neurology palliative care program at the University of Colorado in 2013 (6,14). In this manuscript we will describe some of the successes and challenges of this clinical program, including our current clinic operations and lessons from the initiation of the clinic, as well as supplemental information from two programs at other institutions. We also provide data from a one-year retrospective review of this clinic and a formal quality improvement project with the hopes of facilitating the implementation of similar clinics. We conclude with suggestions for further research and educational initiatives.

Methods

Description of clinic initiation, operations, and growth

We describe the planning and initiation of our neurology palliative care program and related programs at Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) (15) and the University of Toronto and Alberta (UAlb) (6). We also describe our current clinic operations and plans for the growth of this clinic. Our clinic was initiated in 2013, OHSU in 2014, Toronto in 2008, and Alberta in 2014.

Formal quality improvement project

In June 2013 we conducted a quality improvement project with the primary goals of: (I) assessing the clinical needs, perceived gaps in care, and treatment preferences of patients and caregivers; (II) identifying the needs and perceptions of neurologists and palliative care providers; and (III) developing materials and procedures to facilitate clinic operations, data collection, and referrals. Between September 2013 and April 2014, a satisfaction survey was administered to patients and caregivers attending the clinic (Appendix 1). Using a Likert scale from 1–10, patients were asked to rate different aspects of the visit, such as if the clinic visit met expectations, helpfulness of the clinic visit, likelihood of recommending the clinic to others, and satisfaction with services of each team member. Patients and caregivers were also asked open-ended questions about their experience by a study coordinator outside of the clinic team (LT Palmer). During this time period, one of the authors (BM Kluger) held focus groups with other neurology divisions, community neurologists, and several hospices to understand the needs and perceptions of other clinicians.

Retrospective chart review

A retrospective review of all patient encounters from October 2014 through October 2015 was performed to extract information on patient demographics, including age, gender, principal diagnosis, source of referral (internal vs. external), and reasons for referral. For patients who had died at the time the chart review was completed in April 2016, place of death was recorded. We also recorded which team members participated in each encounter, the presence of a caregiver at each encounter, whether a referral to hospice care was made, and the total duration of each encounter. Documentation of medical durable power of attorney and advance directives was recorded and classified as “Completed prior to visit,” “Completed at initial visit,” “Discussed but not completed,” and “not completed.”

Results

Current clinic operations

We currently hold two half-day interdisciplinary clinics per week with additional appointments available for follow-up with a physician assistant at other times during the week.

Scheduling

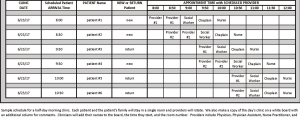

We will typically see four to six patients during a four-hour half-day clinic (Figure 1). New patients usually start with a physician and then see all other team members sequentially, even if only briefly, so that they understand resources available to them. We found that when we left the choice of team member visits to the patient they often excluded the chaplain, despite the fact that we found the chaplain visit to be one of the most valuable during our quality improvement project. Most follow-up visits can be completed solely by a physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner although there are some patients who benefit from multiple visits with the full team. Other clinics have multiple team members in the room at the same time which reduces redundancy in history-taking and may improve interdisciplinary interactions, but may be less time efficient (typically two to four patients per half day) and provide less individual attention with team members.

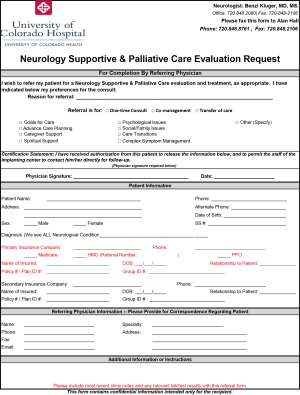

We freeze at least one urgent slot per half-day clinic as it is not infrequent to receive urgent referrals for patients who are doing poorly or experiencing an abrupt decline. Over the past four years, we are seeing a higher percentage of patients earlier in their disease course, likely as a result of improved knowledge of referring providers and increased access. Referring physicians may select their preference for follow-up care including options for a one-time consultation, co-management, or transfer of care (Appendix 2).

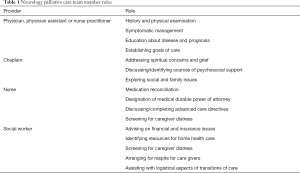

Team membership and roles

Our core team includes a physician, physician assistant, social worker, chaplain, and nurse (Table 1 for roles). We refer to other community services (e.g., acupuncture) and psychotherapists but do not include them in our core team due to concerns of visit length and clinic space. Notably, our chaplain provides significant counseling for our patients and families, particularly as many of their emotional issues are driven by existential concerns. As many of our patients are referred for home physical, occupational, and speech therapy we do not include these disciplines in our core team but are fortunate to be in close proximity to the outpatient rehabilitative clinic and create urgent same-day visits for patients when needed. OHSU’s core team includes a physical therapist (PT) and speech language pathologist (SLP). The PT’s role of maximizing independence and safety is extended to include other quality of life concerns and symptoms, such as incontinence and pain. The SLP addresses complex communication and swallowing challenges. The UAlb team includes a palliative medicine specialist.

Full table

Clinic logistics

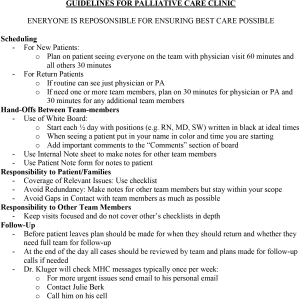

See Appendix 3 for our guidelines on clinic operations. This system was developed to reduce redundancies in history provided by patient, to reduce delays between providers, to ensure that high priority issues are addressed by the appropriate team member, and to quickly orient students, residents, and fellows. We mail patients an intake form which includes standard medical history as well as questions concerning patients’ and families’ goals and fears to focus our conversations and save time during our initial visit.

Continuity of care

We typically remain involved with our patients receiving home palliative care or hospice by having our neurologist stay on as the attending physician. To prevent disruptions in care related to hospitalizations, we have instituted a process of providing patients with a wallet card which includes our contact information and instructions to tell the admitting team “I am a patient of the Neurology Supportive and Palliative Care Clinic at the University of Colorado Hospital. Please do not make any changes to medication without contacting this team.” Finally, if we are notified that a patient has died, we will send a condolence card to the patient’s family and include an invitation to contact us if there is anything more we can do (e.g., bereavement counseling).

Team self-care

We have instituted a daily ritual of meeting as a team at 9 AM to check-in for the day with how we are doing, set our individual intentions for the day (e.g., to be present with the person in front of me; to focus on empowering rather than helping families), and to sit for a brief mindfulness reading. At 4 PM we again meet to review the day, including any follow-up plans, state something we are grateful for, revisit our intention, and process any difficult situations or emotions. This ritual has been well-received by team-members and helps with maintaining our focus and energy for the sacred work we are doing.

Collaboration with palliative medicine

We have grown with the guidance of our palliative care program. We informally consult our palliative medicine colleagues for timely questions and have set days (typically one half-day every two months) where a palliative medicine physician will join us in clinic for our more challenging cases. Other outpatient programs have more palliative medicine input, including having a palliative physician as part of their core team (UAlb). We have cultivated excellent working relationships with several community hospices through invited meetings and ongoing communication, many of whom have expanded their intake of neurologic patients as a result of this collaboration. We routinely discuss and refer our patients to hospice who meet current Medicare Guidelines or have other justification for a life-expectancy of under 6 months (16). We utilize home palliative care for patients who do not meet these criteria but would benefit from these additional home services.

Education experience and other programs

Our clinic provides a mentored experience in neuropalliative care for medical students, neurology residents and fellows, geriatrics fellows, and palliative medicine fellows. Other programs that have grown from our palliative care approach include a monthly group clinic for newly diagnosed PD patients and their caregivers. This clinic, modeled on a similar clinic at OHSU (17,18), grew from research suggesting that the time of diagnosis was a particularly challenging time for patients and caregivers (19) and that patients and families often felt lost and abandoned during this time.

Lessons from the preparation and initiation phase of our clinics

Seeking guidance from established clinics

Prior to initiating our clinic, the director (BM Kluger) visited and spoke with other outpatient palliative care programs serving cancer, heart failure, and PD in the United States and Canada. These visits helped guide the creation of clinic materials, scheduling, and the logistics of working within a interdisciplinary team.

Building a committed team

Our initial team consisted of a neurologist, nurse, chaplain, social worker, psychologist, and acupuncturist. All members of the team were highly interested in palliative care for this population and we took several months to plan our initial clinic including what services we would provide, what patients we would initially serve, and how the clinic would operate. OHSU similarly took six months to build their team prior to opening the clinic. In bi-monthly meetings they reviewed the literature, learned palliative care principles from the director of palliative care and other palliative care experts, developed a vision statement, planned for clinic operations, and developed ground-rules of shared leadership between team members and other team values.

Naming the clinic

We started as the “Neurology Palliative Care Clinic” but quickly changed our name to the “Neurology Supportive and Palliative Care Clinic” due to misperceptions and misgivings on the parts of both patients and referring clinicians regarding the term “palliative.” Other programs call themselves “Next Step Clinic” (OHSU) and “Complex Symptom Management Clinic” (UAlb).

Moving forward with informal training

While some members of our team had prior formal experience in palliative care (nurse, chaplain), there were aspects of the clinic and our patient population that were new to all team members. Informal training included readings, workshops at national meetings, mentoring from experts with complementary skills (e.g., palliative medicine), learning from each other, and learning from patients and families. We invited a palliative medicine physician (J Kutner) to attend several of our early clinics to provide input on the clinic’s services, flow, and documentation. For clinics that are led by palliative medicine specialists, workshops, readings, or mentorship from neurologists may be suggested. Formal training may result in a steeper learning curve and opportunities for neuro-palliative care training are becoming more widely available.

Starting slowly

We began with a half-day clinic once a month and continued with this low volume and frequency as we optimized our clinic flow and procedures. When informing others of the existence of our clinic we have been mindful to not seek referrals without making sure we had the capacity to absorb new patients within an acceptable waiting period. By starting small and growing slowly we have also been able to avoid processes of formal administrative approval required for larger programmatic initiatives.

Finding sources of financial support

Early sources of financial support included philanthropic donations from grateful patients and personnel support from community organizations (e.g., our social worker was initially supported by the Parkinson Association of the Rockies). Other potential sources of support include research grants, quality improvement initiatives, Center of Excellence funds (e.g., through national disease organizations), and internal support. In building a case for internal support we argued that this clinic would provide an important service to our patients and the community, raise the visibility of our program, and improve patient access in other sections of the Department of Neurology by caring for some of their most time-intensive patients.

Incorporating research and tracking outcomes

As this is a new field, we felt that research was important to our mission and that our clinical work could provide data collection for manuscripts and pilot data to support clinical trials. Data that is being collected at our and other institutions to track outcomes include the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (PD modification), Modified Caregiver Strain Index, use of hospice, and place of death (6,20).

Quality improvement initiatives

Neurologists and palliative medicine specialists were generally enthusiastic about the program although there were some neurologists who felt that they already were providing palliative care and had no need for these services. These conversations improved clarity on our referral forms and reinforced the importance of developing clinics integrated within neurology, rather than developing a process where patients were sent off to the cancer center or another department for palliative care.

Over the course of our one-year formal quality improvement initiative we were able to attain patient satisfaction scores of 8–10 for almost all items, including scores above 9 for overall clinic satisfaction and likelihood of recommending the clinic to others. Substantive changes that were made as a result of patient and caregiver input include.

Visit duration

When we started, our average visit length was three to four hours and included five to six disciplines. Over the year we cut the acupuncturist and psychologist from our team and reduced our average visit length to 2.5 hours. With 72% of respondents reporting visit length to be right, 26% too long, and 2% too short we feel we have found a suitable target. We try to be flexible in shortening visits for patients expressing fatigue or lengthening visits for patients with high interest in delving more deeply into complex issues. Splitting patient and caregiver dyads to be seen separately by different providers also allows for more individual attention.

Team communication and roles

Patients commented positively on the clinic structure and thoroughness of their evaluation with the team but felt that gaps between providers could be improved as could redundancies in the history patients provided. In addition, 7% of 39 respondents reported that important issues were not discussed during their visit and specifically mentioned wanting more time spent on education around their diagnosis and prognosis. To address these issues, we developed checklists for each provider (online: http://apm.amegroups.com/public/system/apm/supp-apm.2017.10.06-4.pdf) and a process for providers to checkout in person or through our whiteboard key issues that should be addressed by other team members (Figure 1 and Appendix 3). Several patients indicated that they would prefer more time with the neurologist. This issue was addressed by making follow-up appointments primarily with the neurologist or physician assistant and starting visits with the neurologist.

OHSU uses a verbal team communication system to minimize the burden on patient and family and redundancies. A pre-clinic 30-minute team meeting is used to discuss the six scheduled patients (three new patients and three return patients), review pre-assessment questionnaires, and assign schedules. The patient and family remain in a room and all team members rotate through the rooms. The first team members see the patient/family for 45 minutes after which time there is a 15-minute team meeting. This mid-point meeting provides guidance for the remaining disciplines and prevents the patients from having to repeat themselves. During the next 45 minutes the remaining team members see the patient/family. At the end of this period there is another 15-minute team meeting where a jointly derived plan of care is finalized. This plan is in the electronic medical record and all team members have added to it over the course of the visit. This plan is refined and then relayed in written and verbal form to the patient/family by the neurology provider.

Clinic materials

Of the 39 respondents, 55% said the clinic was as expected, 22.5% were unsure, and 5% stated that the clinic was better than expected. Knowledge of palliative care before receiving the packet was rated 4.3 and helpfulness of the information packet (online: http://apm.amegroups.com/public/system/apm/supp-apm.2017.10.06-5.pdf) in increasing understanding of palliative care was rated 7.6. The chaplain provides a booklet of activities to build resilience and manage grief (online: http://apm.amegroups.com/public/system/apm/supp-apm.2017.10.06-6.pdf). The social worker provides local resources on services, such as in-home healthcare providers, disability lawyers, home safety, support groups, exercise groups, transportation, assisted-living facilities, and hospice as applicable.

Follow-up plans

During the course of the quality improvement project we found that suggestions from team members were not systematically provided to patients and that confusion regarding follow-up plans was common. We thus instituted a process of having the first team member interacting with a patient bring in a take-home sheet for patients on which each team member could write. We also added a process to our check-out procedure at the end of the day to determine if and when patients needed a follow-up call, who on the team should make the call, and plans for follow-up visits.

Retrospective chart review

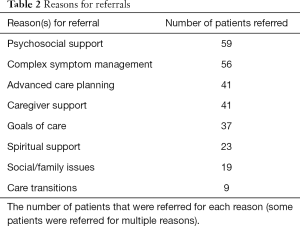

A total of 96 patients (45 female, 51 male) were seen in 117 clinical encounters and a caregiver was present during the visit for 99 of these encounters. The average age was 65, with a range of 25–87 years. Almost all patient (n=91) referrals came from University of Colorado Hospital affiliated providers (internal referrals). The most common referral reasons (Table 2) were for psychosocial support (n=59), complex symptom management (n=56), and advanced care planning (n=41). At the time the chart review was completed 10 patients had died. Location of death for six of these patients was at home with hospice care or in a hospice facility; one death occurred in a hospital with inpatient palliative care, and one in a skilled nursing facility. The location of death was unknown for two patients. Data on duration of new patient encounters were available for 60 of 75 new patients, who were seen for an average duration of 123 minutes, and for 31 of 42 return patients, who were seen for an average duration of 102 minutes. The clinic physician saw all patients. The social worker, chaplain, and nurse were involved in 87%, 76%, and 64% of clinical encounters respectively.

Full table

Medical durable power of attorney had been established prior to the initial visit for 65 (68%) patients, completed at the initial visit for 22 (23%), discussed but not completed for 3 (3%), and not discussed with 6 (6%). Advanced directives had been established prior to the initial visit for 56 (58%) of patients, completed at the initial visit for 20 (21%), discussed but not completed for 12 (13%), and not discussed with 8 (8%). For patients with whom a discussion about establishing medical durable power of attorney and advanced directives did not result in completion of these tasks, additional time was needed to consider these decisions. Seven of eight patients with whom advanced care directives were not discussed declined the offer to have this discussion. We find that among patients with completed advance directive forms, they are frequently completed without medical input (e.g., done with a lawyer), are of questionable clinical utility, and may not truly reflect patient wishes. We thus will always review these outside forms (often over 10 pages with significant legal jargon but without clear instructions on whether or not to resuscitate) and replace them with our states’ or provinces’ standard one page form (e.g., Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment).

The most common principal diagnosis was PD (n=34) followed by PD dementia (n=16), MS (n=8), progressive supranuclear palsy (n=6), Lewy body dementia (n=5), Alzheimer’s disease (n=5), multiple system atrophy (n=4), Huntington’s disease (n=3), corticobasal syndrome (n=3), hereditary spastic paraplegia (n=3), and unknown (n=2). There was one patient each with a diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Meige syndrome, Batten’s disease, chronic fatigue syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 2, and ALS.

OHSU also did a quality improvement review and found that providers were saved 1.5 hours/patient by facilitating coordination of care and cross-discipline communication. Patients were saved time and travel by integrating four to five services into a single visit. The University of Toronto previously published their experience of reducing symptom burden using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale modified for PD (6).

Discussion

Outpatient palliative care for neurology provides several valuable services to this population including improved caregiver support, complex symptom management, in-depth goals of care discussions, psychosocial and spiritual support, and assistance with transitions in care, including hospice. There is an emerging literature suggesting that this model of care improves patient outcomes and also lowers healthcare costs (6,8). This clinic also provides value to the department and community as an educational resource, including meeting Accreditation Data System and Case Log System requirements for neurology residents in palliative care (21). We have built a successful research program in palliative care beginning with pilot data collected in clinic and using the clinic and feedback from patients and families as a living laboratory to optimize our intervention and related materials. Projects have included efforts to better define palliative care needs of patients and families, comparative effectiveness trials of this clinic model, and dissemination and implementation efforts (NCT 02533921, NCT 03076671). Another advantage in terms of research include improving our reach to patients with advanced disease who often stop coming to neurologists or academic centers. One of the central principles of palliative care is non-abandonment and we have found that neurology patients and their families continue to find value in our services even with very advanced disease.

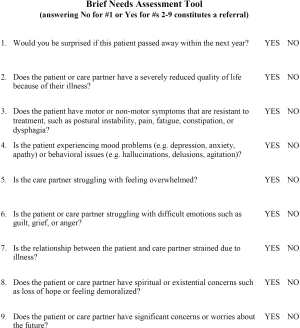

The mix of patient diagnoses seen likely reflects the clinic developing from a mixed movement disorders and behavioral neurology clinic. Had the clinic developed from another disease-driven clinic (e.g., ALS), it is likely that the early distribution of patients would be different. The other factor affecting the mix of patients is our local clinician culture, with some clinicians and sections who are very familiar and comfortable with the idea of palliative care and understand how it benefits their patients while others are more resistant or are holding on to ideas that they need to wait for “the right time,” which typically means that referrals are either never made or only after a crisis such as a hospitalization. As this is a new field, we are working to educate our colleagues and are piloting the use of a new Needs Assessment Tool (Appendix 4) as both a way to educate clinicians and standardize patient selection. Given the experience of palliative care in oncology, we anticipate cultural change and acceptance of palliative care within neurology will take place over time with some change coming from education of more experienced clinicians and much being driven by persons currently in training or junior faculty. In general, we have found younger faculty, residents, and students more accepting of the palliative care approach and more likely to refer patients earlier in their disease course when more proactive measures can be undertaken.

Although we do not have data from a randomized controlled trial, the data presented here and other case series suggest an increase in hospice use and decrease in hospital deaths with outpatient palliative care (22-24). Amongst those patients dying in the hospital, some are unexpected and sudden illnesses which reflects the unpredictability of decline in neurologic illness. Among these, several did contact our clinic and were able to get palliative care in place in the hospital. Notably, several patients’ and families’ goals are to pursue aggressive care even towards the end of life and we try to support those wishes while maintaining communication around these goals and the opportunity for changing goals if and when their preferences change.

Ongoing challenges for our clinic and other similar clinics include financial limitations, ensuring access to care, and institutional and political barriers to optimal care. Our clinic has been able to maintain financial solvency through a combination of physician billing, philanthropy, research grants, and hospital and departmental support. The costs and income associated with such a program will vary based on many factors including the composition of the team, the ability of team members to bill for their services, the costs of space and staff, and the manner in which patients are scheduled. We believe such clinics can exist with minimal institutional or outside support but this may require some creative staffing. Finally, as we delve deeper into this work we encounter many institutional, policy, and political barriers to optimal care ranging from the limited options for non-medical home-based support of patients to idiosyncrasies in the funding and provision of hospice care. As a program we are connecting with others in the community to help advocate for this population.

The clinics described in this paper all subscribe to a model of integrating palliative care with disease-modifying therapies throughout the course of the illness (25). However, due to workforce and cost issues, we also recognize that our specialized palliative care clinics should be reserved for challenging patients and is only a small part of our overall mission to improve the care of patients with neurologic disorders through a palliative approach (26). Education of other faculty in primary palliative care skills and the development of group clinics and community resources are also essential to supporting the full spectrum of palliative care needs (19).

Our neuropalliative care program has experienced steady growth since its inception and is now its own section within our neurology department with three full time faculty and several other faculty members with joint appointments with their disease-specific section (e.g., movement disorders, behavioral neurology). We envision our program growing in an embedded manner with integrated programs dedicated to specific disorders (e.g., dementia, movement disorders, MS, ALS). We are also working with geriatrics to develop a neurodegenerative medical home for patients and caregivers where they can get both neurology and primary care in a single integrated experience and on expanding telehealth from ongoing research projects to provide virtual house calls for patients with mobility issues, including those in hospice or nursing facilities. We are interested in providing more general resources to the department, including other group clinics on topics like advance directives, legal and financial resources for families, and chronic disease management. Lastly, we are initiating a dedicated neurology track in our palliative care fellowship to start summer 2018.

As recognition has grown of the high palliative care needs of patients and caregivers affected by neurologic disease, so too has interest in finding approaches to meet this need (9-11). The first Neuropalliative Care Summit at the 2017 American Academy of Neurology meeting brought together neurologists from around the world interested in this field. One of the most promising aspects of this summit was the high percentage of fellows and junior faculty, many of whom were launching their own outpatient clinics. One of the themes of this summit was that in addition to looking for cures tomorrow we need to provide better care today. We believe that outpatient neurology palliative care is central to this mission.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank D Bekelman, E Bruera, W Cernik, MK Christian, C Friedman, N Galifianakis, M Katz, R Khan, C McRae, J Youngwerth, and the many patients and families who attended our clinic for their input and inspiration in shaping our neurology palliative care program and Robert Holloway and Claire Creutzfeld for initiating the Neuropalliative Care Summit. The authors would like to thank Candace Ellman for her assistance in preparing and submitting the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a University of Colorado Hospital Clinical Effectiveness and Patient Safety Program grant for quality improvement. Additionally, research reported in this publication was partially funded through a Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IHS-1408-20134). Lastly, research reported in the publication was partially supported by the Nation Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01NR016037.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Disclaimer: All statements in the publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix 1 Patient satisfaction survey.

Appendix 2 Outside referral form.

Appendix 3 Guidelines for palliative care clinic.

Appendix 4 Brief needs assessment tool.

References

- Palliative care in neurology. The American Academy of Neurology Ethics and Humanities Subcommittee. Neurology 1996;46:870-2. [PubMed]

- Oliver DJ, Borasio GD, Caraceni A, et al. A consensus review on the development of palliative care for patients with chronic and progressive neurological disease. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:30-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van den Block L. The need for integrating palliative care in ageing and dementia policies. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:705-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2014;28:197-209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marin B, Beghi E, Vial C, et al. Evaluation of the application of the European guidelines for the diagnosis and clinical care of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients in six French ALS centres. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:787-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyasaki JM, Long J, Mancini D, et al. Palliative care for advanced Parkinson disease: An interdisciplinary clinic and new scale, the ESAS-PD. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18 Suppl 3:S6-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walbert T. Integration of palliative care into the neuro-oncology practice: patterns in the United States. Neurooncol Pract 2014;1:3-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, McCrone P, Hart SR, et al. Is short-term palliative care cost-effective in multiple sclerosis? A randomized phase II trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:816-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boersma I, Miyasaki J, Kutner J, et al. Palliative care and neurology: Time for a paradigm shift. Neurology 2014;83:561-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson MT, Barrett KM. Emerging subspecialties in neurology: neuropalliative care. Neurology 2014;82:e180-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Creutzfeldt CJ, Robinson MT, Holloway RG. Neurologists as primary palliative care providers: Communication and practice approaches. Neurol Clin Pract 2016;6:40-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Gunten CF. Secondary and tertiary palliative care in US hospitals. JAMA 2002;287:875-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cunningham C, Ollendorf D, Travers K. The Effectiveness and Value of Palliative Care in the Outpatient Setting. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:264-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewin WH, Schaefer KG. Integrating palliative care into routine care of patients with heart failure: models for clinical collaboration. Heart Fail Rev 2017;22:517-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Su KG, Carter JH, Tuck KK, et al. Palliative care for patients with Parkinson’s disease: an interdisciplinary review and next step model. J Parkinsonism RLS 2017:1-12.

- Medical guidelines for determining prognosis in selected non-cancer diseases. The National Hospice Organization. Hosp J 1996;11:47-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boersma I, Jones J, Carter J, et al. Parkinson disease patients' perspectives on palliative care needs: What are they telling us? Neurol Clin Pract 2016;6:209-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phillips LJ. Dropping the bomb: the experience of being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. Geriatr Nurs 2006;27:362-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hall K, Sumrall M, Thelen G, et al. Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: suggestions from a council of patient and carepartners. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2017;3:16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyasaki JM, Kluger B. Palliative care for Parkinson's disease: has the time come? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2015;15:26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- (ACGME) ACfGME. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Neurology. 2017. Available online: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/180_neurology_2017-07-01.pdf?ver=2017-02-21-082421-197

- Sleeman KE, Ho YK, Verne J, et al. Place of death, and its relation with underlying cause of death, in Parkinson's disease, motor neurone disease, and multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Palliat Med 2013;27:840-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Snell K, Pennington S, Lee M, et al. The place of death in Parkinson's disease. Age Ageing 2009;38:617-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCluskey L, Houseman G. Medicare hospice referral criteria for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a need for improvement. J Palliat Med 2004;7:47-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Provinciali L, Carlini G, Tarquini D, et al. Need for palliative care for neurological diseases. Neurol Sci 2016;37:1581-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lupu D. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:899-911. [Crossref] [PubMed]