Compassionate communities: design and preliminary results of the experience of Vic (Barcelona, Spain) caring city

Introduction

The experiences of compassionate communities

Palliative care has been extending across the health systems from the initial experiences at the British hospices, focused on the institutional care of patients with terminal cancer, creating different types of services and adapted to different cultures (1). In recent years, several innovations have been developed: timely palliative approach for people with advanced chronic conditions in the community, including the care of elderly with multi-morbidity or with organ failures (2), developing psychosocial and spiritual care as elements of comprehensive care (3), or integrated care networks, or conventional Public Health approach with the aim of universal coverage, equity and quality in the health care system (4,5). All these innovations have been focused on health services initially in specialist palliative care services and lately in all settings of care, but without actively involving the community, except for implementing volunteer programs linked to these services.

More recently, a more civic concept has been developed as part of a wider conception of public health, consisting in the active involvement of the community in the design, care and implementation of palliative care policies (6). This new approach, with origins in the 1990s experience of the state of Kerala (India) (7) and the early public health policies and practices in Australian palliative care (8), consisting of the active involvement of the community and population in the design and care. This civic conception has often been identified by the name of “compassionate communities” (or cities)—when a community takes the leadership with the aims of changing the cultural and social perspectives and actions towards death, dying, loss and caregiving and promotes a civic program of social action to care for people with advanced chronic conditions, applying the values of compassion, humanism, and solidarity, and linked to similar social initiatives (9-11). A specific charter has been developed as definition and standard (12).

There are examples of successful experiences (13-16) and some models have been developed, including policies and standards, and methods for evaluation as well (17-21). An international network has been created to establish cooperation and to promote this approach (22) as an innovative and wider development of palliative care and public health. In Spain, several initiatives have been started, and a cooperative group of the SECPAL (Spanish Society for Palliative Care) has been created recently.

The city of Vic

Vic is an old city of 43,964 inhabitants in the Centre of Catalonia, with an ageing population (21%), a high proportion of immigration (26%), and a complete range of social and health services (23).

The experience of palliative care in Vic and Catalonia

Palliative care was initiated in Vic in 1984, when a home care support team based in the Oncology Service started to attend patients with terminal cancer at home. In 1987, a comprehensive palliative care system based at the Hospital de Santa Creu was implemented, including the Palliative Care Unit, a Hospital Support Team, and the Home Care Support Team. These were the 1st palliative care services in Spain and were the basis for the design of the Catalan Palliative Care project. This Project was designated WHO Demonstration Project in 1990 and has been implementing palliative care services and palliative approach for chronic patients recently and showing results regularly (24). The Catalan system has implemented a wide range of specialist palliative care services, and more recently, the palliative care approach for people with advanced chronic conditions in the community (25).

This context of high coverage for palliative care specialist services and palliative approach in the community integrated in the system has created the conditions to develop a wider social and cultural perspective in the city, to enhance the social components of a global Public Health approach.

Methods

This paper describes the principles, aims, initial phases and activities, and preliminary results of the project “Vic, Ciutat Cuidadora” (“Vic, caring city”, VicCC), in the context of the Compassionate/Caring Community program.

Methodology

Consists of the description of the construction, generation of consensus and partnership, and establishment of mission, vision, aims, initial activities, the preliminary results, and the proposal for evaluation as well.

The project of VicCC

Initial actions

The initial actions consisted in establishing contact with the International Association Public Health Palliative Care International (22) to understand the basis of these programs, and explore the availability and feasibility of implementing a similar project in the city of Vic.

Aims, mission, vision, and values

Aims

The aims of the VicCC were proposed by the leading team and agreed with the partners and defined globally and with a time frame of short, mid, and long term. Globally, the aims consist in promoting socially positive attitudes towards end of life (EoL), increasing awareness and social actions, and developing integrated social support for people with advanced chronic conditions in the community. In the short term (0–2 years), the proposed aims were to build consensus, promote participation, and start the informative, cultural, and training activities. In the mid-term (2–5 years) the start of the care/supporting activities, develop and implement volunteer activities, enhance all organizations to insert EoL policies, evaluate results, and assure sustainability. In the long-term, we propose to have high coverage and impact in the society and extend to other vulnerable people.

Mission

To prevent and alleviate suffering, specifically adapted to EoL and for most vulnerable people.

Vision

To achieve positive cultural and social attitudes and actions towards the EoL

To have a comprehensive and integrated care system for people—from civic to health service actions—at the EoL in the city.

To be a reference for a systematic approach, implementation and evaluation of projects with a Public Health approach.

Main characteristics

The VicCC project is characterized by a strong joint leadership, social and community predominant perspectives, in a mid-size city with a long tradition of palliative care and social caring organizations.

Values

Humanism, compassion, social participation, equity, coverage and quality (from Public Health approach) with a community perspective were central.

Name/title and slogan

Both concepts were discussed openly with the organizations. In a formal meeting, there was a discussion about the title, and the majority of the attendants preferred to use the term “Cuidadora” (“Caring” in Catalan) as compared with “Compassiva” (“Compassionate”). The main reasons to do so were related to the cultural identification of “compassion” with religion, and the broader meaning of “Cuidadora”. The slogan agreed was “Viure amb sentit, dignitat i suport al ſinal de la vida” (“Living the end of life with meaning, dignity, and support”). We emphasized the inclusion of the terms “meaning” and “dignity” as individual issues combined with “support” due to the social environment. The final leaflet of the project included the aims, values and mission of the whole program (Figure 1).

Leadership and team

The leadership was shared between the Department of Social Welfare of the City of Vic, the Chair of Palliative Care at the University of Vic (Barcelona) linked to the WHO Collaborating Centre for Palliative Care Public Health Programs based at the Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona. The team was composed by professionals coming from the Chair, the Primary Care Services and from the Welfare Department at the Council of Vic.

A group of eight organizations composed the “core nucleus” of the project, helped in the design of activities, and met regularly for follow up.

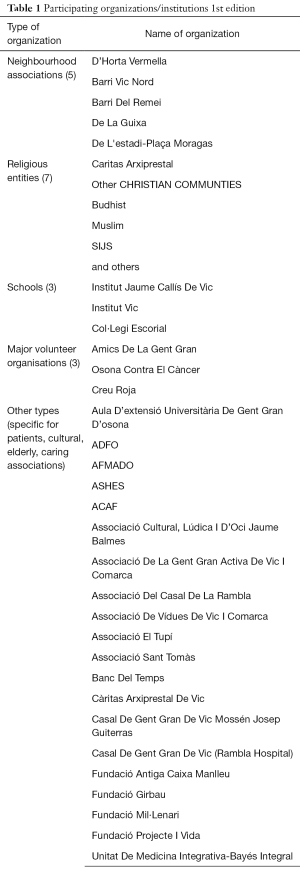

Proposed organizations and partners (Table 1)

Full table

We used the list of the social organizations at the Welfare Office, and selected the most active among NGOs, religious, schools, neighbours, support, and others for the first phase. A total number of 48 organizations were contacted and all agreed to participate, with different degrees of commitment.

Sponsors

A call for sponsors was made among known local or national organizations. In the first phase, we achieved support from a local Foundation (Girbau Foundation) and two national organizations (La Caixa Foundation and Mémora Foundation) that covered the expenses. The Chair of Palliative and the City Hall gave also some funding and devoted partially their structure.

Phases: based in the Charter for Compassion (11 cross reference) and the Kansas University Community Tool Box (17)

- Needs and demands assessment: estimation of people at the EoL and social needs, survey and workshop The mortality who or where are we talking about has been of 347 people at the year 2017. The estimation of the prevalent population at the EoL is of 650 people (26), most of them, elderly with multi-morbidity. Around 200 (0.4% of population) have added complex social needs as isolation, poverty, and limited access of services at home.

- Survey A formal meeting was performed, and a semi-structured survey was sent (n=48) to all the organizations. The structure of this survey included their background on the topic, and their needs, demands, expectations and willingness to participate. Looking at these responses, we elaborated the proposal of agenda. The main needs and demands identified were the training, the cultural debates, and the need of organizing the support of the most needed people through volunteers and pathways linked to the community health and social services when an individual need is identified. Additionally, the partners were required to establish policies and protocols to promote positive attitudes and volunteer proposals in their organizations.

- “Foundation workshop” A workshop titled “How to involve society in end of life” was organized and performed on the 16th June 2016. The program included a lecture by Professor Allan Kellehear, a lecture of presentation of the main aims of the program and the leading team, and a participative workshop to promote consensus around the project. A total number of 64 participants attended, representing most of the partner organizations. This workshop was the first activity proposed to the organizations. As a result of the workshop, a general consensus on the basic principles, vision, mission, aims, and values were achieved.

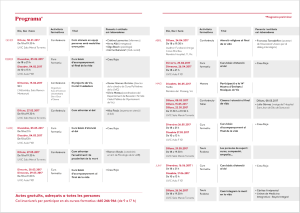

- Activities and agenda elaboration After the survey and workshop, and based on the suggestions, we elaborated the proposal of activities. According to their aims, format, and targets, the activities were categorized into “Training” (Workshops), “General information” (lectures, round tables), “Cultural” (Cinema, literature), or “Mixed” and planned over the year. A total number of 19 activities were planned and performed during the first year (Figure 2).

Results

The evaluation of the first year of implementation included quantitative and qualitative methods and was performed combining the evaluation of the project done and shared between the core team and the organizations, the training activities by the attendants, and with the stakeholders (funders, political leaders).

Quantitative results

The quantitative assessment was focused mainly in the registry of 48 organizations, and the activities and attendants for each activity. The most remarkable data are: the number of activities (n=19), the participation of 64 persons to the workshop, 1,260 attendants to the activities, and 147 attended the training courses (1,470 in total).

Qualitative

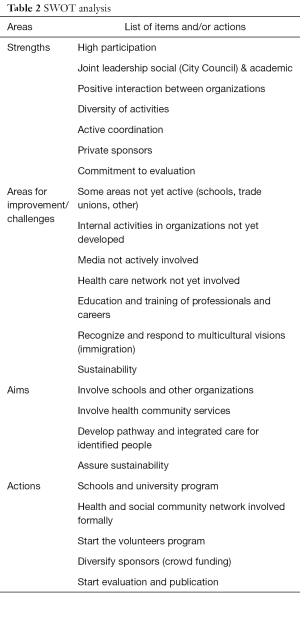

Qualitative SWOT assessment

The SWOT analysis was performed by the organizations and the core team and included a formal letter (including a survey) and a formal meeting. A total number of 12 organizations responded, and 8 attended the specific evaluation meeting.

The results are described in Table 2. The general view was highly satisfactory, with several strong points. Some areas for improvement and topics to be proposed were identified.

Full table

Survey of the attendants to training activities

A semi-structured survey (Likert scale 1–4) was conducted and proposed to the attendants of training activities. A total number of 51 responded. The topics were considered relevant (3.67/4), clarity in the exposition (3.75/4), dynamic and participation (3.24/4), and time and dates (3.51/4).

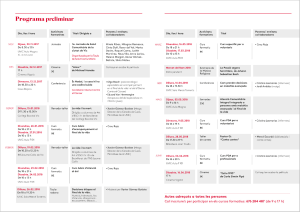

Proposals 2017/18 (Figure 3)

Based on the qualitative, SWOT and analysis, we introduced several changes in the program for the 2nd year, the main aims identified were to expand, consolidate, and start make the program more oriented to care.

These aims were expressed in new targets (schools, other organizations,), introducing different types of activities (concerts, social), increasing the media actions, and inserting the program into the community health and social networks to provide integrated care for people identified with needs, and starting the care activities of volunteers. The targets of this care activity are defined by the existence of a complex advanced chronic condition and limited life prognosis (identified by the NECPAL tool in the community) with additional complex social needs (isolation, poverty, limited accessibility, or relational conflict).

Discussion

A comprehensive program of Compassionate community in the city of Vic was established. In the context of a city with a wide range and high coverage of palliative care specialist services, this program aimed to modify social and cultural perspectives and actions towards EoL and promote a comprehensive and integrated system for people with advanced chronic conditions and complex social needs, especially in the community. The program has been l jointly led by the Welfare Area of the City Council and the Chair of Palliative Care at the University of Vic.

The Program is based in The Compassionate City Charter criteria and the evaluation tools (10,11,15,16,19,20) adapted to the Latin-Mediterranean cultural context.

The phase I (“Discover and Assess”) has been completed with the three steps (identifying needs and discomforts, identify what has been already done by the organizations, and invite community (leaders, organizations) responses.

The phase II (“Focus and Commit”) with the steps 5, 7, and 8, has been done organizing the workshop and the semi-structured survey to all organizations, and elaborating mission, aims, objectives, and agenda for 1 year, and presenting formally the project by the Major of Vic). The step 6 (register) is being currently implemented.

The Phase III (“Build and Launch”) with the steps 9, 10, and 11, was implemented between September 2016 and June 2017, with a wide range of activities (see Figure 2).

We are developing the phase IV (“Evaluate and sustain”) with the systematic quantitative and qualitative assessment, and the recommendations are currently applied to the second-year program.

Challenges identified

The main challenges identified are related to the complexity of social and cultural issues regarding EoL matters, the barriers to the acceptance of EoL and death as natural events, and the need for comprehensive and integrated networks of the health and social services to attend people with chronic conditions and social needs. Different cultural patterns in the context of high immigration need to be considered. Consolidation and sustainability are main challenges and objectives to assure.

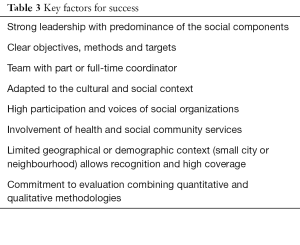

Reasons for success

The main reasons for this initial success might be the strong and joint leadership combining the City Council and the Chair, the high participation achieved, the appointment of a specific coordinator (SS), and the context of a small city with high development of palliative care specialist services and community services as well, implementing very clear and defined program (aims, values), devoted to specific and well-defined targets, oriented to action and committed to evaluation. We achieved also local and regional donors that funded totally the expenses.

Some considerations and recommendations

In our perspective, the main issues to consider for success and recommendations are summarized in Table 3.

Full table

The shared partnership between the Social Department of the City Council and an academic organization as the Chair of Palliative has been successful to create a neutral and respected leadership, with visible social involvement.

The experience of compassionate community is an excellent development of the concept and the organization of a comprehensive network of palliative care, and a step forward in the concept of palliative care as a public health topic.

Society through social organizations must be an active and free leader of the programs and be able to identify areas of improvement and development and influence their presence in the policies and implementation.

Future perspectives

The Program is committed to achieve high coverage (involving more organizations, targets and partners), sustainability (social and economic), and oriented to care of the most vulnerable populations at the EoL. This model might be expanded to other vulnerable populations. There are demands from other cities in the country to implement similar programs. We also started to develop social media resources, based on patient experience research, such as short videos which we will use in public meetings to facilitate public discussion about the EoL (https://www.ed.ac.uk/usher/primary-palliative-care/videos/how-to-live-and-die-well-group-format).

Limitations of this paper

This paper is a description of the main characteristics and preliminary results of a Program of Compassionate Community, not oriented specifically to research. The methodology has been a basic combination of quantitative and qualitative. A systematic qualitative evaluation is currently being designed.

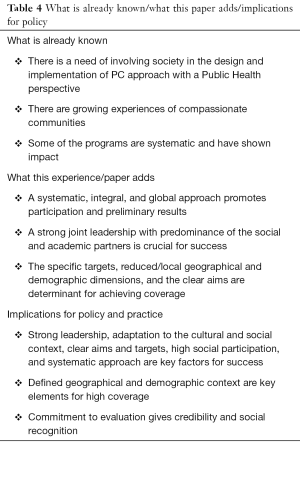

What is already known/what this experience adds to existing knowledge/implications for policy and practice (see Table 4).

Full table

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all organizations that have participated in the project. The authors would also like to thank Mrs Sara Ela for her support in reviewing, providing final editing assistance, and improving this manuscript.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study was approved by all the institutional bodies involved. Explicit ethical information and its ID or written informed consent were not considered a request to be obtained since the report did not affect patients or families and did not imply ethical dilemma of any type. Additionally, the report was recognised as important to public health.

References

- Clark D. From margins to the centre: a review of the history of palliative care in cancer. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:430-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Batiste X, Murray SA, Keri T, et al. Comprehensive and integrated palliative care for people with advanced chronic conditions: an update from several European initiatives and recommendations for policy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:509-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment within the continuum of care. 2014. Available online: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB134/B134_R7-en.pdf. (last accessed 27 December 2017).

- Gómez-Batiste X, Connor S. editors. Building Integrated Palliative Care Programs and Services. Catalonia: Liberdúplex, 2017.

- Kellehear A, Sallnow L. Public health and palliative care: An historical overview. In: Sallnow L, Kumar S, Kellehear A. editors. International perspectives on public health and palliative care. New York: Routledge, 2012:1-12.

- Kumar S. Public Health approaches to palliative care: the neighbourhood network in Kerala. In: Sallnow L, Kumar S, Kellehear A. editors. International perspectives on public health and palliative care. London: Routledge, 2012:98-109.

- Kellehear A. Health Promoting Palliative Care. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Kellehear A. Compassionate communities: end-of-life care as everyone’s responsibility. QJM 2013;106:1071-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abel J, Walter T, Carey LB, et al. Circles of care: should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:383-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abel J, Kellehear A. Palliative care reimagined: a needed shift. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:21-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kellehear A. The compassionate city charter: inviting the cultural and social sectors into end of life care. In: Wegleitner K, Heimerl K, Kellehear A. editors. Compassionate Communities: case studies from Britain and Europe. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2016;76-87.

- Paul S, Sallnow L. Public health approaches to end-of-life care in the UK: an online survey of palliative care services. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:196-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sallnow L, Kumar S, Kellehear A. editors. International perspectives on public health and palliative care. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Wegleitner K, Heimerl K, Kellehear A. Compassionate communities: case studies from Britain and Europe. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2016.

- Abel J, Bowra J, Walter T, et al. Compassionate community networks: supporting home Dying. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011;1:129-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Community Tool Box. Building compassionate communities. Section 16. Center for Community Health and Development. Kansas University. Available online: (last accessed 27 December 2017).www.ctb.ku.edu

- South J. A Guide to community-centred approaches to Health and wellbeing: full report. Public Health England, London, 2014. Available online: (last accessed 27 December 2017).https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-and-wellbeing-a-guide-to-community-centred-approaches

- O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, McDaid D, et al. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2013 Nov. (Public Health Research, No. 1.4). Available online: (last accessed 27 December 2017).https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK262817/

- Sallnow L, Richardson H, Murray SA, et al. The impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2016;30:200-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karapliagkou A, Kellehear A. Public Health approaches to end of life: a toolkit. Available online: (last accessed 27 December 2017).http://www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Public_Health_Approaches_To_End_of_Life_Care_Toolkit_WEB.pdf

- Public Health Palliative Care International. Available online: (last accessed 27 December 2017).http://www.phpci.info/

- Official statistics website of Catalonia. Government of Catalonia. Available online: Accessed 31 January 2018.https://www.idescat.cat/

- Gómez-Batiste X, Blay C, Martínez-Muñoz M, et al. The Catalonia WHO Demonstration Project of Palliative Care: results at 25 years (1990-2015). J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52:92-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Batiste X, Martínez-Muñoz M, Blay C, et al. Identifying chronic patients in need of palliative care in the general population: development of the NECPAL tool and preliminary prevalence rates in Catalonia. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:300-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Batiste X, Martinez-Muñoz M, Blay C, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of patients with advanced chronic conditions in need of palliative care in the general population: a cross-sectional study. Palliat Med 2014;28:302-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]