Palliative care—the new essentials

Introduction

In an earlier publication, Abel and Kellehear (1) examined the potential for reshaping palliative care services by applying the principles of the public health approach to end-of-life care. The public health model of palliative care has shown promising evidence of effectiveness (2-6). The social justice basis for this approach responds to the crucial need for equity of care irrespective of age, background, diagnosis, or cause of death. In the current paper, we propose a practical model that redesigns and reshapes services, by inviting and organising the coordination and interaction between specialist palliative care, generalist palliative care, compassionate communities, and the civic approach to end-of-life care (7). The seamless integration of these four components, which are already part of some end-of-life care systems around the world, offers the possibility of uniting professional care with community resource. The outcome of the proposed partnership is inclusive care irrespective of cause of death, and opportunities of support for the bereaved in equal measure. We argue that these four components and their collaboration will provide the new essentials that will help us reshape palliative and end-of-life care.

The first part of this paper describes the four components of the proposed model in order to define the core terms of reference for this discussion. We will then describe how the four components should work together, in order to more effectively promote issues of importance to health and wellbeing at the end of life—not solely for the dying patient, but also for caregivers, and the bereaved. The final part of the paper makes recommendations for changes in professional service organisation and social practices, starting from changes within the organisation and operations of the core components.

Palliative care components

National health services around the world are organised differently. The key components of care entailed in the proposed model may be found to a greater or lesser extent in all national healthcare systems. The challenge for respective national palliative and end-of-life care services will be to fulfil the functions of the model we describe according to the needs of their local organisational and community structures.

Specialist palliative care

There is no single or clear definition of specialist palliative care (8). The World Health Organisation defines palliative care as ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.’ (9). This definition comes as a subheading under ‘cancer’ and does not make a specific reference to non-cancer terminal diagnoses and conditions. It also does not differentiate between specialist and generalist palliative care.

Many countries recognise palliative care as a medical speciality with training programmes equivalent to other accredited specialities, or at least sub-specialities. Similarly, there are recognised training programmes for specialist palliative care nurses. Specialist palliative care can perhaps best be conceived within a spectrum of care services attending to the needs of those who do not need extensive support, as well as those who need focussed attention in a variety of care settings, at different stages in their illness. The domains of care involved are broad and inclusive of physical, social, psychological and spiritual needs. For this reason, the grey area between specialist and generalist palliative care remains, and the differentiation of the four components into neat categories proves challenging.

The differentiation between specialist and generalist palliative care can be better understood if we consider the nature of severe care needs. In the case of specialist palliative care, patients require complex assessment with specialized therapeutic knowledge (as in the case of management of malignant bowel obstruction or complex neuropathic pain). In generalist palliative care, routine healthcare is combined with social care to allow patients to live with their condition at home. However, even within the context of specialist palliative care, many hospice patients in inpatient units have similar social needs.

The proportion of inpatients who need palliative care is estimated at 63% (10). The proportion of inpatients who need specialist palliative care is difficult to estimate and determine. What we do know is that non-cancer patients are under-represented in specialist palliative care, although they have comparable needs to cancer patients (11). Ethnic minority community members, older people and marginal groups (i.e., homeless populations) have also been documented to escape timely referral to specialist palliative care services (12). In other words, specialist palliative care could be more readily available to people who are in receipt of generalist palliative care, while social care needs to reach people closer to death and in receipt of specialist palliative care in equal measure. By and large, in those countries that have palliative care recognised as a specialty, the care provided is for patients with complex needs and symptom control problems. Instead, there needs to be a continuum of support between specialist, generalist, community and civic end-of-life care, so that those who mostly need specialist services can readily access it.

Generalist palliative care

Generalist palliative care can be defined by exclusion—it is not a medical specialty, and involves care at the end of life that is not provided by specialist palliative care teams. This means that it includes care provided by all health and social care professionals who look after people who are dying and those who are bereaved. The issue of who provides generalist palliative care depends upon each individual country healthcare system, its organisation and regulations. In the UK, most hospital specialities look after terminally ill patients, and may be supported to a greater or lesser extent by in-hospital specialist palliative care teams. Outside the hospital setting, care is coordinated by primary care teams, consisting of general practitioners, trained nursing staff, social workers and nursing staff who give physical hands-on care. Professionals who provide palliative care may be supported by specialist teams for complex problems, but this is commonly restricted to cancer patients.

Although there are marked improvements in specialist palliative care provision in the UK—with more people seen in inpatient units, and a higher number of beds being available or in use—the number of non-cancer patients in specialist palliative care inpatient units is 11% (13). It has been established that non-cancer patients with terminal diseases have comparable need for specialist palliative care with cancer patients, but further research is needed to identify their specific needs and types of care received in order to draw directions for their inclusion (11).

Compassionate communities

Compassionate communities are naturally occurring networks of support in neighbourhoods and communities, surrounding those experiencing death, dying, caregiving, loss and bereavement. Conceptually and practically, these networks have been defined by ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ circles of care (14,15). The ‘inner’ circles of care typically consist of between 3 and 10 people who are closely related to the person with the illness. They usually provide personal (physical) care, as well as companionship, psychological and emotional support. The ‘outer’ circles of care consist of between 5 and 50 people or more, with an average number of 16 (16). The ‘outer’ circle is not focussed exclusively on the patient, while members may not necessarily know one another. The ‘outer’ circle of care helps with the ‘stuff’ of life—the shopping, the cooking, the cleaning, lifts to and from hospital appointments, gardening, dog-walking, and more. In a study of family caregiving for cancer patients, the average number of hours per week spent on these tasks was 62 (17)—a sizeable proportion of which could be shared with community members, neighbours and friends within the network.

Community support for the entire network will vary depending upon the level of community activation that has taken place. For example, community volunteers may be happy to perform small practical tasks and offer companionship while existing charitable or religious institutions may offer and organise such supports. The ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ circles of care, and neighbourhood supports are the main foundation of resilient networks caring for people at home. Together they form a Compassionate Community.

Compassionate communities may include an element of what is widely known as ‘social prescribing’ (18). However, it is important to remember that it is not primarily that activity which defines their action. Social prescribing is often a way that patient populations are connected—or reconnected—to their communities by linking their personal lives with new social activities and networks that were previously unknown to, or little used by them—book clubs, walking clubs, coffee mornings, gym classes, befriending groups, and more. These kinds of referrals work well enough for physically mobile populations, but work less well, or not at all, for those largely confined to home for mental or physical health reasons, or for reasons of geography or financial barriers. Compassionate communities bring networks to people, whilst social prescribing requires people to go to the networks. Both types of movement are useful in compassionate communities, but social prescribing alone favour mainly those in better health, a resource less common in end-of-life care circumstances.

Civic end-of-life care

Professional services, such as specialist or generalist palliative care, give and receive support from communities to enhance their respective tasks of support for people with life-limiting illness and their caregivers. In the same way, communities or neighbourhoods require support from civic sectors to effectively undertake their responsibilities towards people with end-of-life care needs. Professional support is incomplete without community support, especially in matters to do with quality and continuity of care. In the same way, community support cannot offer continuity or quality of care without civic participation and co-operation from public sectors and institutions—schools, workplaces or churches. This is quite simply because these are the key social institutions inhabited by the very neighbours, family members, or friends offering support to the dying or the bereaved. It is, therefore, crucial to recognize that neighbourhood caregivers are not faceless social entities but rather actual employees, students, worshipers, shoppers, and club members. The civic component of end-of-life care recognizes this foundational inter-dependency as the very support basis of community care, and mobilises actions that support end-of-life care in public institutions.

Although there are potentially numerous ways we can involve business or schools in end-of-life care, the Compassionate City Charter (7) provides a succinct and ready-made tool for embedding this approach to end-of-life care. The Charter includes action recommendations for schools, workplaces, churches and temples, trade unions, cultural centres, hospices and care homes, amongst others. Reorientation of health care towards civic partnerships, as described in the Ottawa Charter of Health Promotion (19) is a consistent part of the public health approach to end-of-life care. A variety of incentive schemes to promote participation from the different social and cultural sectors, and an annual memorial parade, are all part of the actionable aspects of engaging people at the broadest community level in end-of-life care. The Charter does not define how it should be put into practice. This is something that is different in each context and depends upon who owns the initiative of becoming a Compassionate City, as well as how the Charter is adapted for different national circumstances. However, the principles apply across the globe. In the context of communities, the word ‘city’ is etymologically associated with its core social element—the citizen—and is taken from the Latin root word civitas, which describes shared civic responsibilities that transcend traditional tribal barriers (such as those of gender, ‘race’ or social class), a common purpose, and a sense of community.

Palliative care—the new essentials model

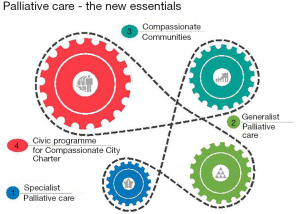

The New Essentials model proposes a way of integrating the processes and operations of the four basic components—specialist palliative care, generalist palliative care, compassionate communities and civic end-of-life care—that make up palliative and end-of-life care. Their effective coordination aims at improved wellbeing at the end of life for every citizen affected by a life-limiting condition.

In Figure 1, each component is represented by a cog which is united by a chain joining them all. Together, they work to drive up the benefits of the hierarchy of wellbeing at the end of life, which we describe in Figure 2. The absence of any one of the cogs means that the promotion and reproduction of wellbeing is disrupted, and the clinical and public health effectiveness in addressing the co-morbidities associated with dying, caregiving, or loss will be undermined. We will discuss the benefits of using each cog, and the risks resulting from their absence.

Having understood that it is the union of all four components that sustains end-of-life care, we will make suggestions on how professional services can reshape and reorganise within the framework of a complete end-of-life care system with public health priorities. The linkage between the cogs and the mutual participation in joint initiatives is needed in order to be able to realistically provide end-of-life care and bereavement support for all, irrespective of age, background, and diagnosis.

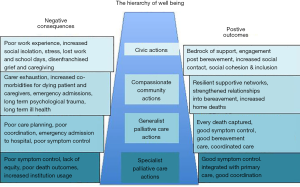

Figure 2 portrays ‘The Hierarchy of Wellbeing’ representing both the negative consequences of poor care (generated by individual but disjointed palliative and end-of-life care components), and the ideal positive outcomes (generated by individual but co-operating palliative and end-of-life care components). The left-hand side column describes the social and clinical epidemiological consequences and poor health service and social care and support. The right-hand side column describes the equivalent positive outcomes. It is important to note here, that many of the poor outcomes we commonly associate with the dying or bereavement journey—such as depression, loneliness, or ‘compassion fatigue’—overlap or are better explained as system failures in professional service or social support systems. However, without an optimal level of public health practice in end-of-life care—the New Essentials as we describe them here—it is not easy to distinguish between the pure social and psychological consequences of facing mortality and loss, on one hand, and the polluting social and psychological consequences of poor care, on the other.

The challenge in building collaborative partnerships between the four key components of palliative and end-of-life care, and coordinating their respective processes is that the practice represents an innovation with multiple readjustments. Specialist and generalist palliative care, for example, have a limited range of therapeutic options, while network enhancement and linkage to community resource that would naturally expand their possibilities, is not a routine part of their therapeutic tools. Compassionate communities are struggling to access the domain of professional practice, gain acceptance and establish effective communication that will allow them to take a more active role in care. Civic engagement in end-of-life care is not fully understood yet in societies where healthcare is perceived as a professional responsibility.

This means that significant domains of care and support are left untapped and professional services alone cannot fill these gaps. The roles and practices of professional, community and civic care are naturally complementary and not mutually exclusive. Care in general, and palliative and end-of-life care in particular, is achieved through the mutual efforts of specialist and generalist palliative care, community care and civic end-of-life care. The palliative care—New Essentials framework proposes actions for the expansion of their collaboration, aiming to improve inclusion of specific needs, as well as citizens who find themselves marginalised in care. The remainder of this paper considers the roles and properties of each of the components, and offers recommendations for their adaptation, aiming to bridge their practices and promote greater inclusion in care.

Specialist palliative care recommendations

Current specialist palliative care services fulfil a variety of functions ranging from inpatient specialist palliative care beds in hospices and in hospitals, outpatient services, community visiting, advice and support in primary care and the community, and in-hospital teams for symptom control and advice. Carers’ feedback from the VOICES 2015 survey (20) clearly demonstrates the impact and benefits of high quality palliative care. In particular, for those patients who receive hospice care, the feedback about the quality of care is almost always excellent.

This can be in stark contrast to the experience of end-of-life care in other settings—hospitals or communities—where specialist services may be limited (21-23). This is particularly, but not exclusively, the case in non-cancer terminal illnesses (23,24), people of lower socio-economic background and non-English speakers who tend to benefit less by specialist palliative care services in hospital settings (25). Young male cancer patients were found to benefit more from specialist palliative care referrals (23). Opportunities for advance care planning and building of supportive networks are also missed, and crises precipitate unplanned admissions to hospital—as in the case of heart failure patients that fail to receive advance care planning and specialist palliative care services early in their illness (26). The marked difference in home and hospital death rates between those with a diagnosis of cancer and those with non-cancer terminal illnesses—cancer patients are more likely to die at home (27,28) —is a consequence of lack of identification of the final phase of terminal illness, and lack of specialist palliative care in the community among the latter.

The organisation of specialist palliative care services relies upon the basic principle that supportive communities can do much of what is currently being done by professional specialist teams. Outpatient care, and community specialist care form partnerships with informal care to allow terminally ill patients to spend time or die at home. A strong and resilient supportive community is better able to cope with the stresses and strains of caring for someone who is dying. Examples of how this is done come from Australia, where a networking approach to palliative care in the community has been adopted (29,30). Building strong networks means that patients can be looked after at home if members of the ‘inner’ circle of care are trained in caring skills, such as manual handling and medication administration. Strong ‘outer’ circles within the caring networks support those closer to the person who is dying in a variety of ways. They may take care of simple everyday tasks and provide respite and emotional support.

Similarly, the adoption of the civic approach to end-of-life care and the implementation of the Compassionate City Charter creates awareness about end-of-life care needs and provisions of support in the spaces and environments where citizens socialise, work, study and engage in various activities. Citizens who engage with the end of life and its care, and are encouraged to do so by the very social sectors and public institutions they interact with on a daily basis, are more likely to form partnerships with professional healthcare services and assist in the delivery of care in the community. The attitude of compassion and practical support that they encounter at school, work, society, club or centre of worship will be transferred to private sectors where palliative and end-of-life care can be burdensome and isolating.

Resilient support networks can fulfil and enhance a variety of functions ordinarily performed by professional services. Spiritual, psychological and social care are not the exclusive domain of professionals. Meaning and value in care is equally obtained in the context of supportive communities, and the same principle applies to physical care. Once strong social networks are in place, it is possible to consider changing the roles and functions of specialist palliative care services to enable the formation of partnerships with community and civic sectors and supports. Table 1 summaries our recommendations for achieving the above goals for specialist palliative care.

Full table

In the UK all residents have access to primary care services. This means that GP services are notified of all deaths, including the place where death occurred. This creates the possibility of ensuring universal coverage of palliative care through review of each death. However, not all health services have primary care teams, and not everyone has access to healthcare. The key challenge in these circumstances is to build reliable health systems that provide equity of care to all who need it. Solutions to these problems are place dependent. Generic solutions often do not fit individual circumstances. Aiming for the key function of universal coverage should be an aspiration for all palliative care teams.

Generalist palliative care recommendations

Gaps in the provision of generalist palliative care are common, and occur in a variety of different ways. Every healthcare professional is responsible for attending to the needs of people with life-limiting conditions. Generalist palliative care, therefore, takes place in different settings, at hospitals, in primary care, and in the community. The complexity of generalist palliative care makes it difficult to predict and organise into concrete processes and therapeutic practices. As a result, the challenges of inclusion cannot be effectively addressed. The final phase of life may go unrecognised, undermining peoples’ chances to receive advance care planning for better symptom control. Characteristically, there is little concurrence among medical and nursing staff over which individual patients have palliative care needs. Concurrence is only increased with proximity to death (31). In cases where death is sudden like in heart disease, any opportunities to advance care planning may be missed, and death may result after a hospital admission, to the distress of patients and caregivers (26).

Emergency admissions to hospital without recognition of end-of-life care needs equally undermine the opportunity to build resilient networks and prepare for care at home. Aggressive treatments in a situation of crisis and lack of communication with healthcare professionals can lead to distressing experiences for relatives and friends, which have long-term consequences, and impact upon bereavement (32). Finally, the coordination of care can be problematic—General Practitioners express discomfort about their ability to perform palliative care adequately (22). They may miss symptoms not treatable by them or less common. When supported by specialist palliative care teams their effectiveness increases, and patients are able to benefit from palliative care support, including social care prior to an acute crisis. Inadequate care of the terminally ill impacts negatively among their bereaved caregivers. Adverse circumstances at the time of death complicate bereavement experiences and lead to longer-term poor health outcomes (33).

Generalist palliative care, even more so than specialist palliative care, has limited therapeutic options to its availability, and is often called to deal with acute crisis in situations where specialist palliative care has not intervened with advance care planning. Being reliant on professional care alone means that when this care is not available, it can be quite challenging to help and support in an effective way. For example, the most difficult times for primary care teams is in an acute situation when urgent social care is needed, but is not readily available. The situation is currently compounded by budget cuts in health and social care. A collaborative approach between health and social care has been recommended as a way to deal with limited resources (34). Adopting a community and civic approach to end-of-life care adds to the suggested partnership.

Compassionate communities will first examine whether community resource, primarily within the patients’ own supportive network, can provide care at short notice. If community resource building has taken place, there may be support groups that could provide some kind of help in the short-term whilst supportive networks are being built, and while health and social care mobilise their own resources. The coordination of care would require a specific initiative facilitated by a community development worker embedded within the clinical care team. Longer-term resilient network building is best started early in the patient’s journey. Although a lot of palliative care does not rely upon direct patient contact, and involves practical or psychological and social support, equipping networks with skills in caregiving and pain control should be routine for everyone identified as being at the end of life. Equally, the training needed does not have to be given by professionals, but could be community-led, by groups that have already had training and experience in caring for someone who has died.

Generalist palliative care, like specialist palliative care, focuses largely on harm reduction as prescribed by the public health approach to end-of-life care (35). This is primarily achieved through early identification, advance care planning and prevention of admission to hospital within the framework of a multifaceted approach with good attention to symptom control. The social elements of the model reduce harm that comes from the difficulties of caring from the point of diagnosis right through to bereavement. For this purpose, and for the reasons mentioned above, generalist palliative care would benefit from effective collaboration with specialist palliative care and social care, but also from efficient communication with caring communities, equipped with knowledge and skills to support the end of life. Table 2 summarizes the recommended actions form primary care.

Full table

Compassionate communities recommendations

A change that would make a difference to the reorganisation of palliative care services is the development of collaborative relationships with compassionate communities. Compassionate communities rely upon the principle of civic responsibility to care for end of life needs, and their formation can be initiated by healthcare services or community and charitable organisations alike. Supportive networks formed within the framework of compassionate communities may contain anywhere between 10 and 100 people, depending upon the method of network mapping employed. This is an enormous community resource that makes a difference between a successful, resilient network that can look after someone throughout the course of their illness, and that of a weak network that results in a hospital admission during a crisis.

A community development programme initiated by healthcare services themselves can add value and enhance available resources and support. This is particularly important for people who have limited naturally occurring networks. Development of supportive networks and community resource for end-of-life care requires the employment of a community development worker. If this resource is to be available to both primary care teams and hospitals, the community development worker needs to be integrated into the clinical teams. Building relationships and common working practices requires collaboration on joint initiatives. This is a practice that needs to overcome the major obstacle of siloed working in institutions and services. Community development by its very nature cross cuts multiple organisations and services. For this purpose, community development for compassionate communities, as an interdisciplinary and participatory activity, will help healthcare services transcend boundaries that reinforce exclusion and limit care.

The last phase of life presents increased care needs and/or leads to unplanned admissions to hospital in a situation of crisis. Evidence to this is that people who are being admitted to nursing homes do so more frequently during the last six weeks of life (36). This indicates that nursing homes take on much of the burden of end-of-life care. It may be that building strong resilient networks can provide a community solution to this particular problem. In this way, those who want to stay in their homes for the course of their illness will be able to do so. Network building is a skill that has to be learnt, through experience and through training. Network building is also a skill that community members can practice for themselves, without continuous input from professionals. Running training programmes for community members and professional carers alike is, therefore, a key component of building resourceful communities.

People who develop strong supportive networks at the end of life establish relationships that last for years (14). This is important in helping to combat the sense of lack of meaning and value that is part of the challenge of having a terminal illness (37,38), or caring for someone at the end of life (39). A sense of ‘togetherness’ that comes from participation in social networks and recognition as a person who is caring for someone with a life-limiting condition, and, therefore, grieving, also helps to alleviate the fundamental problems of social isolation and loss experienced during bereavement (40). These are issues that adversely impact upon health in the long-term, causing psychological morbidities and increased mortality risks (33,41).

Bereavement is associated with worse health outcomes indicated by the presence of physical symptoms and increased use of medical services (33). It has been estimated that bereavement impacts upon hospital inpatient days, and adds to the cost of healthcare services by between £16.2 million and £23.3 million per year (42). The same study found that in the long-term (2 years post-loss), bereaved people were still distressed, and more likely than non-bereaved individuals to be out of work. If we also take into consideration the economic, social and psychological consequences of bereavement the overall impact is likely to be considerable (43,44). It is not a coincidence then that during the early days and months of death, there is increased mortality risk among the bereaved - depending upon experiences of caring and circumstances of death (33,45).

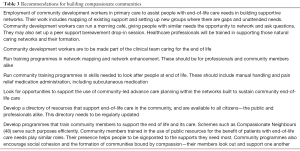

By joining forces with compassionate communities, healthcare services can do much to support the health and wellbeing of carers and the bereaved. Such partnerships are more likely to improve carers’ experience at the end of life, as well as address the issue of continuing bereavement care post-loss (46). One of the main reasons that people with caring needs avoid building supportive networks is that they do not want to be a burden to others. Post-loss they are also more likely to withdraw and lose all available supports (14). However, based upon the experience of people involved in similar roles and responsibilities, burden is not an issue. Rather, research on volunteering in end-of-life care indicates that caring for someone who is dying is seen as a privilege (47). Compassionate communities in healthcare settings can promote engagement with end-of-life care matters and alleviate concerns that exclude and isolate. Table 3 summarizes the recommendations for the creation and maintenance of compassionate communities working in partnership with clinical teams.

Full table

Civic end-of-life care recommendations

Compassionate cities are communities that publicly recognize these populations, and these needs and troubles, and seek to enlist all the major sectors of a community to help support them and reduce the negative social, psychological and medical impact of serious illness, caregiving, and bereavement. A compassionate city is a community that recognizes that care for one another at times of health crisis and personal loss is not simply a task solely for health and social services but is everyone’s responsibility (7).

The domains of caring for someone at the end of their lives are not limited to homes, local neighbourhoods, or health care institutions. The experiences of caring are also not limited to solely the main carer but extend through whole caring networks and communities. These experiences are carried through into our wider social domains and activities—our workplaces, schools, places of worship, and countless other social institutions. These social worlds underline and cradle our spiritual experience—our experiences of meaning-making in the face of everyday life and personal crises—and we carry them with us wherever we are. Furthermore, in population health terms, each of us will experience loss and bereavement multiple times in our lifetime. This naturally means we need to find ways of helping and supporting those undergoing these experiences at an everyday level. We need to ensure that when death, dying, caregiving, and loss visit us that—wherever we are, and whoever we are—satisfactory support will be found in all the relevant life worlds that we inhabit.

The Compassionate City Charter (7) is a succinct way of organising a purposeful programme of civic action oriented towards the end of life. The Charter is drawn from the principles of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (19,49). The key point in the implementation of the Charter is that most of the individual action points need to be progressed. This does not have to be done all at once but plans do need to be put in place to make sure all the necessary actions are commenced at some point. Some actions may be less relevant for some communities—for example, some communities may not have prisons or refugees. In these cases, adopting communities may need to examine what vulnerable or marginalized groups need instead to be considered in their local area. Art galleries or museums may not be crucial in a particular city or town but other cultural sites and activities may be more relevant. Each community will need to carefully consider how the Charter may need to be modified to create the most effective and impactful civic actions that support their local communities in their participation for end-of-life care. Some basic recommendations on how to start this process is summarized in Table 4.

Full table

There is no single right way of instigating and implementing civic action, including use of the Compassionate City Charter. The key component is enthusiasm of a core group of individuals or institutions who want to take an initiative forward. Ideally, as broad a coalition as possible should be involved. This can prove to be difficult with slow moving bureaucracies or engaging elected representatives when these change on a regular basis. It is sometimes necessary to begin a project on a small scale and gradually expand it to become more inclusive. In addition, what works in one place will not necessarily work in another, which means that each area will need to find its own solutions of how to run a civic programme.

Conclusions

Academic and clinical textbooks on Palliative Medicine commonly promote a model of care that is professional-led and health services oriented. There is little emphasis on the importance of the role of community and social relationships in healthcare at end of life. Given that social relationships are a crucial determinant of health (50), finding ways of integrating this into routine healthcare is important for medicine as a whole and palliative care in particular. Community and civic models of action and how these may be partnered and synergized with professional action have been far less common. When the ‘social’ aspects of care are advocated, recommendations and discussions focussed upon support groups or ‘psychosocial’ actions that reduce or confine community involvement to volunteer services or small-scale neighbourhood supports.

We have argued that a health-promoting palliative care service—one designed and fit for purpose as a population health model—must embrace a co-operative model of practice and service design that seamlessly fuses the different levels of clinical and community expertise. This means that it is essential for palliative care to realise a co-operation between specialist and generalist palliative care services, working in partnership with local communities, and the broader civic sectors of society that support and sustain those communities. Each individual sector acting in isolation will not work for palliative and end-of-life care. Rather, the recognition of their inter-dependence, and effective co-operation will make each individual part—specialist and generalist palliative care, compassionate communities and compassionate cities—the New Essentials for palliative care.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Abel J, Kellehear A. Palliative care reimagined: a needed shift. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:21-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumar SK. Kerala, India: A regional community-based palliative care model. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:623-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton, McDaid D, et al. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library, 2013.

- South J, Stanfield J, Mehta P, et al. A Guide to Community-centred Approaches to Health & Wellbeing: Full Report. Public Health England 2014; London. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/402887/A_guide_to_community-centred_approaches_for_health_and_wellbeing.pdf

- Sallnow L, Richardson H, Murray SA, et al. The impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: A systematic review. Palliat Med 2016;30:200-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cronin P. Compassionate communities in Shropshire, West Midlands, England. In: Wegleitner K, Heimerl K, Kellehear A. editors. Compassionate Communities: Case studies from Britain and Europe. Routledge, Oxon, 2016:30-45.

- Kellehear A. The Compassionate City Charter: Inviting the cultural and social sectors into end of life care. In: Wegleitner K, Heimerl K, Kellehear A. editors. Compassionate Communities: Case Studies From Britain and Europe. Routledge, Oxon, 2016:76-87

- Pastrana T, Junger C, Elsner F, et al. A matter of definition - key elements identified in a discourse analysis of defitions of palliative care. Palliat Med 2008;22:222-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Definition of Palliative Care (Internet). Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Murtagh FE, Bausewein C, Verne J, et al. How many people need palliative care? A study developing and comparing methods for population-based estimates. Palliat Med 2014;28:49-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luddington L, Cox S, Higginson I, et al. The need for palliative care for patients with non-cancer diseases: A review of the evidence. Int J Palliat Nurs 2001;7:221-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed N, Bestall JE, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Palliat Med 2004;18:525-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The National Council for Palliative Care, Public Health England. National Survery of Patient Activity Data for Specialist Palliative Care Services: MDS full report for the year 2011-2012. The National Council for Palliative Care, London, 2012.

- Abel J, Walter T, Carey LB, et al. Circles of care: should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013. Available online: http://spcare.bmj.com/content/early/2013/03/05/bmjspcare-2012-000359

- Horsfall D, Noonan K, Leonard R. Bringing our dying home: creating community at end of life. Cancer Council New South Wales, New South Wales, 2012.

- Horsfall D, Yardley A, Leonard R, et al. End of life at home: Co-creating an ecology of care. Research report, Western Sydney University, Sydney, 2015.

- Rowland C, Hanratty B, Pilling M, et al. The contributions of family care-givers at end of life: A national post-bereavement census survey of cancer carers’ hours of care and expenditures. Palliat Med 2017;31:346-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bickerdike L, Booth A, Wilson PM, et al. Social prescribing: less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013384. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- WHO. The Ottawa charter for health promotion: first international conference on health promotion, Ottawa, 21 November 1986. WHO, Geneva, 1986.

- Office for National Statistics. National Survey of Bereaved People (VOICES): England, 2015. Quality of care delivered in the last 3 months of life for adults who died in England. Office for National Statistics, London, 2016.

- Smith TJ, Coyne P, Cassel B, et al. A high-volume specialist palliative care unit and team may reduce in-hospital end-of-life care costs. J Palliat Med 2003;6:699-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell GK. How well do general practitioners deliver palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat Med 2002;16:457-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- To THM, Greene AG, Agar MR, et al. A point prevalence survey of hospital inpatients to define the proportion with palliation as the primary goal of care and the need for specialist palliative care. Intern Med J 2011;41:430-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seow H, Brazil K, Sussman J, et al. Impact of community based, specialist palliative care teams on hospitalisations and emergency department visits late in life and hospital deaths: a pooled analysis. BMJ 2014;348:g3496. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Currow DC, Agar M, Sanderson C. Populations who die without specialist palliative care: does lower uptake equate with unmet need? Palliat Med 2008;22:43-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Small N, Barnes S, Gott M, et al. Dying, death and bereavement: a qualitative study of the views of carers of people with heart failure in the UK. BMC Palliative Care 2009;8:6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- EOL Profiles: Cause and Place of Death - CCG [Internet]. [cited 18.12.2015]. Available online: http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/profiles/CCGs/Place_and_Cause_of_Death/atlas.html

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Higginson IJ. Reversal in British trends of place of death: TIme series analysis 2004-2010. Palliat Med 2012;26:102-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horsfall D, Higgs J. Palliative Care. Community-Based Healthcare: Springer, 2017:123-32.

- Horsfall D, Leonard R, Rosenberg JP, et al. Home as a place of caring and wellbeing? A qualitative study of informal carers and caring networks lived experiences of providing in-home end-of-life care. Health Place 2017;46:58-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gott MC, Ahmedzai SM, Wood C. How many patients in an acute hospital have palliative care needs? Comparing the perspectives of medical and nursing staff. Palliat Med 2001;15:451-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet 2007;370:1960-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larkin M, Richardson EL, Tabreman J, et al. New partnerships in health and social care for an era of public spending cuts. Health Soc Care Community 2012;20:199-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kellehear A, O’Connor D. Health-promoting palliative care: A practice example. Crit Public Health 2008;18:111-5. [Crossref]

- Kelly A, Conell-Price J, Covinsky K, et al. Length of stay for older adults residing in nursing homes at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1701-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ettema EJ, Derksen LD, van Leeuwen E. Existential loneliness and end-of-life care: A systematic review. Theor Med Bioeth 2010;31:141-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prince-Paul M. Understanding the meaning of social well-being at the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008;35:365-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dahlborg Lyckhage E, Lindahi B. Living in liminality - Being simultaneously visible and invisible: Caregivers' narratives of palliative care. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2013;9:272-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sjolander C, Ahlstrom G. The meaning and validation of social support networks for close family of persons with advanced cancer. BMC Nurs 2012;11:17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015;10:227-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stephen AI, Macduff C, Petrie DJ, et al. The economic cost of bereavement in Scotland. Death Stud 2015;39:151-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonanno GA, Kaltman S. The varieties of grief experience. Clin Psychol Rev 2001;21:705-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valdimarsdóttir U, Helgason AR, Johan C, et al. Need for and access to bereavement support after loss of a husband to urologic cancers: A nationwide follow-up of Swedish widows. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2005;39:271-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. The health impact of health care on families: A matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:465-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fauri DP, Ettner B, Kovacs PJ. Bereavement services in acute care settings. Death Studies 2000;24:51-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sévigny A, Dumont S, Cohen SR, et al. Helping them live until they die: Volunteer practices in palliative home care. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 2010;39:734-52. [Crossref]

- Attridge C, Richardson H, Muylders S. Building compassionate communities across London and the South East. BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care 2017. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/ [Crossref]

- Kellehear A. Health-promoting palliative care: developing a social model for practice. Mortality 1999;4:75-82. [Crossref]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Bradley Layton J. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000316. [Crossref] [PubMed]