Developing palliative care programs in Indigenous communities using participatory action research: a Canadian application of the public health approach to palliative care

Introduction

Palliative care (PC) integrates physical, psychological, social and spiritual care elements to improve the quality of life for people living with a life-limiting illness and their families (1,2). It honors the connections and relationships that people have with family members, community members, and care providers, and views the family as the unit of care. Culture plays a key role since it incorporates the social practices and beliefs of any group of people (3).

There is growing international interest to improve access to PC for Indigenous people. Research on Indigenous PC is emerging from Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States (4-6). The Indigenous people of Canada include First Nations, Inuit and Metis. This Canadian research focused on developing culturally appropriate PC programs in four First Nations communities.

There are 618 First Nations communities in Canada with approximately 474,000 inhabitants (7,8). Many First Nations communities are small and located in rural or remote regions (8). The aging of Canadian First Nations populations, and their increasing rates of chronic illness and terminal disease, make providing PC for this population a growing social obligation (9). The responsibility for funding Indigenous health rests with the federal government under the Canadian constitution; however, First Nations people also access provincially funded hospitals and health services outside their communities (10,11).

While there is diversity between and within First Nations communities, there are common themes pertaining to end of life. Communities view death as a natural part of the life cycle and care is provided by family and community (12-15). For most First Nations people, the dying experience is sacred and needs to be prepared for according to their beliefs (12). There are established traditions for providing psychological and spiritual support, and long standing social processes for supporting people experiencing dying, loss, grief and bereavement. Further, connection to the land is important, especially to the traditional territories where people grew up and have familial connections (16,17).

While social, cultural and spiritual support is available in First Nations communities, people lack access to PC programs, especially pain and symptom management (9). Absence of social policy to address this issue, and dissention between levels of governments about jurisdictional responsibility for funding, have resulted in a service gap for PC in First Nations communities (6). Additional PC barriers include limited local health services, staff and resources, and lack of training in PC (6). The federal government funds only basic home and community care services (e.g., nursing, personal support) through the First Nations Inuit Home and Community Care Program (HCCP) (18). The limited funding allows services only during the day (Monday to Friday, 8:30 to 4:30), and PC is not funded as a unique service element. Most communities have visiting physicians who come weekly or monthly, depending on the population and location of the community. Many communities have no health services available on evenings and weekends.

Consequently, First Nations people frequently leave their communities to access service that is geographically distant and often culturally unsafe due to differences in language, values, beliefs and expectations (16,19-23). Receiving care outside the community creates alienation and social isolation for First Nations individuals who are separated from their language, culture, Elders, Knowledge Carriers, family and support people (14,16,17,23,24). Although people want to die at home, many die in urban hospitals and long-term care homes (19,20).

Dying outside the community negatively impacts families and community members. It may prevent transmission of culture from one generation to the next (3). Further, dying is a time when the community traditionally gathers to support the family, and these community relationships foster collective resilience. Caregiving provides a shared purpose that builds social and cultural capital (25). Over time, lack of end-of-life caregiving can have a disempowering effect, undermining the community’s collective confidence to care for their loved ones (19). It may also interrupt the community’s collective ability to grieve since social networks promote belonging and emotional healing (26).

Given the issues described for First Nations people, it is increasingly recognized that PC should be developed at the local level. Program models need to be locally relevant and accessible (6,17), and need to be developed in conjunction with community leaders, Indigenous health care providers and the Indigenous community (3,27-32). While the challenges are similar, the solutions need to be community specific (14). Community capacity development, as an approach that is bottom-up and inside out, provides an appropriate conceptual framework for this work.

Community capacity development is consistent with a public health approach—also known as health promoting PC—that approaches end-of-life issues from a social, cultural and community lens (33). Applying the public health approach to First Nations PC has not been done to the knowledge of the authors. It requires: (I) implementing culturally appropriate PC services at the local community level; (II) developing supportive government policies that promote cross-jurisdictional partnerships and funding for required services, medication and equipment to support community-based programs; and (III) providing education of policy makers, health care providers and community caregivers. Generating the knowledge required to implement health promoting PC in First Nations communities provided the rationale for this research.

Methods

Overview of the research

This 6-year [2010–2016] research project was entitled “Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities: Generating a Theory of Change to Guide Program and Policy Development” (EOLFN). The overarching goal was to improve end-of-life care in four First Nations communities through developing PC programs and creating a culturally appropriate theory of change to guide program and policy development. Objectives were to:

- Document Indigenous understandings of PC as a foundation for developing PC programs;

- Generate a culturally appropriate theory of change in First Nations communities based on Kelley’s community capacity development model;

- Create an evidence-based tool kit of strategies and interventions to implement PC programs in First Nations communities;

- Empower First Nations health care providers to be catalysts for community change in developing PC and supportive policy frameworks;

- Improve capacity within First Nations communities by developing PC teams and programs and strengthening linkages to regional PC resources.

Theoretical perspective

The EOLFN research adopted community capacity development as its theoretical perspective. Capacities are the collective capabilities found within and among people, organizations, and community networks and society (34). From this perspective, communities are seen to have the capacity to tackle their problems through collective problem-solving. The method of promoting change is to enhance local capacity and not impose solutions from outside (35). Through this research, researchers worked with First Nations communities to mobilize community PC capacity. Kelley’s Developing Rural Palliative Care (DRPC) model offered the conceptual framework for this research (36).

Kelley’s DRPC model

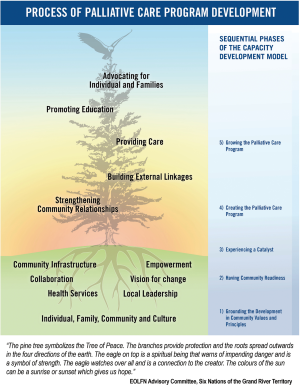

Kelley’s four phase community capacity development model conceptualizes a process of change that builds on existing community capacity and context. Change evolves through four phases: (I) having necessary antecedent community conditions; (II) experiencing a catalyst for change; (III) creating a PC team; and (IV) growing the PC program. The four phases represent a sequential, yet gradual transformative process that ultimately provides clinical care, education and advocacy. Each phase has tasks that must be accomplished, culminating in the delivery of a PC program that is mobilized through strong linkages both within the community and to external resources.

The model incorporates the following principles of community capacity development: change is incremental and dynamic; change takes time; development builds on existing resources and is essentially about developing people; development needs to be “bottom-up”, not imposed from outside; and development is ongoing (36). This validated model is recognized as a guide to program and policy development for rural PC (37-39). In the EOLFN research, this model was adapted to guide creation of a culturally appropriate theory of change for First Nations communities. All aspects of program development were controlled by community members, ensuring the PC program was embedded in the unique social and cultural context of the community.

Ethics

The research was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Lakehead University (REB #020 10-11), McMaster University (REB #10-578), Six Nations of the Grand River Territory and the Chief and Councils of Fort William, Naotkamegwanning, and Peguis First Nations. All participants in the project provided informed consent. Research was conducted following national guidelines for health research with Indigenous people (40), and the principles of Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP®) which are sanctioned by the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) to ensure self-determination in research concerning First Nations (41).

Design

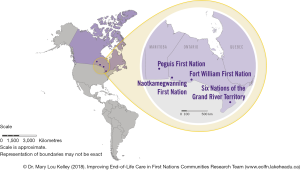

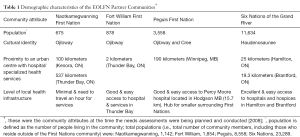

This research followed Prince and Kelley’s Integrative Framework for Conducting Research with First Nations communities which consists of five components: community capacity development, cultural competence and safety, participatory action research (PAR), ethics and partnerships (9). A comparative case study design was adopted using four First Nations communities as study sites (42). The four sites varied widely on relevant dimensions since maximum variation strengthens findings and applicability of results. Differences included: rurality, proximity to an urban health service centre, level of community infrastructure, local health services, population size, cultural identity and provincial health policy environment (see Table 1). Figure 1 depicts the communities’ geographic locations.

Full table

The method was PAR, which generates practical and theoretical knowledge using a social change process (43). The goal is to create social change for participants’ benefit. This paradigm differs from conventional research paradigms in three ways: in its understanding and use of knowledge; its relationship with research participants; and the introduction of change into the research process (44,45). In this research, data were collected through multiple methods: surveys, interviews, focus groups, observations, and workshops. All instruments were reviewed by First Nations’ community advisory committees to ensure cultural appropriateness and adapted as requested. For example, in one community there were changes in language, replacing the words palliative and dying with the words seriously ill and preparing for the journey. Data were collected by facilitators chosen by the advisory committees and paid using research funds.

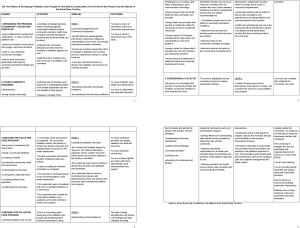

The activities of the research are outlined in Table 2. Activities evolved incrementally and dynamically over the 6 years, from working inside the community (creating local PC programs) to working regionally and nationally on creating partnerships, reorienting health services and changing policy (funding and resources). Consistent with case study design and PAR, each community evolved in a unique way. As needed, the researchers provided mentorship, facilitation, support, education and resources to the community leaders and documented and evaluated their capacity development process (see Table 2).

Full table

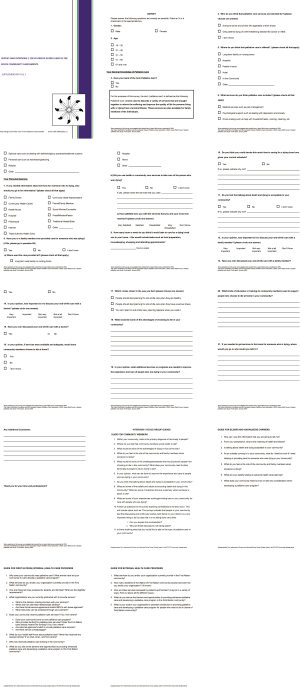

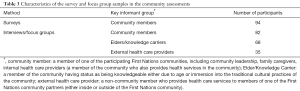

During the research, each community developed their own PC program that was grounded in their unique social, spiritual and cultural practices, and integrated the program into existing health services. Each community created an advisory committee that ensured development was consistent with their vision, community capacity and context. Comprehensive assessments were conducted in each community to understand beliefs and experiences with death and dying, and identify PC education and service needs. These assessments gathered quantitative and qualitative data in two phases. Key informant surveys were followed by interviews and focus groups to provide elaboration and clarification (see Table 3 for participants). The survey and interview/focus group guides are attached as a Supplementary file 1 to this article. A video overviewing the research process is included as Figure S1.

Full table

Guided by the Kelley model and using the assessment findings, multiple clinical, educational, administrative and policy interventions were created and implemented. The research team documented the community development process in each community, generated a workbook of research informed strategies, evaluated use of the Kelley model and identified keys to success.

Results

The results are presented in three sections. Section 1 summarizes the community assessment findings which motivated the action research. Sections 2 and 3 present the research outcomes to guide PC program development and policy and planning.

Section 1: Community assessments

A thematic analysis (50) integrating the findings of the four community assessments is presented below. Individual community reports can be accessed on the project website (51-54).

PC and community caregiving

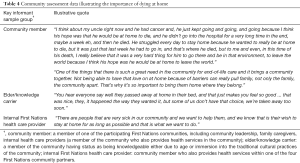

Most (87%) survey respondents (n=94) indicated that community members would prefer to receive their PC at home in the First Nations communities, if local services were available and appropriate to their needs. Table 4 provides quotes illustrating the importance of dying at home.

Full table

Most (81%) respondents also indicated they had cared for someone who was dying. Community members felt it is important for families to be involved in providing care for their loved one who is ill, and that community members should not die alone. Participants described the current state of palliative caregiving in the community below:

“It’s just, probably just the natural ways of the people. Just the way it was I guess a long time ago. People used to help you no matter who he was. If you were on the reserve, people, somebody would get sick, and then people would go down there and the whole family would have support…” —Community Member

“In a First Nation community it’s real extended family who, who have community members there too, and everyone helps and there’s always certain community members that show up and come and stay with the family, give them support, … they bring in food, the whole community does that, and help. They help guide the family through, a, through this grieving process.” —Community Member

Palliative caregiving in the First Nations community is depicted in Figure 2. In the community, a person with a life-limiting illness is normally cared for at home by family members who provide direct care and support (the principal caregiving network). Family is supported by community members who provide both direct and indirect support to the dying person and their family (the internal caregiving network). The internal community caregiving network includes extended family, natural helping networks, Elders and Knowledge Carriers, paid health care providers and leadership (e.g., Chief and Council and local health service administrators). Internal health care providers have ongoing, trusting relationships with community members and most live in the community. The boundary between the principal caregiving network and the internal community caregiving network is depicted as porous because of the importance of kinship and relationships in First Nations communities, and because people often hold dual roles (e.g., internal health care providers are often family members). Community members described supporting one another through death, dying, grief and bereavement.

Although cultural values and beliefs varied, the importance of culture in caring for community members who are dying was highlighted. Community members felt it is important to recognize death as part of life, and that death should not be feared. They spoke of the importance of traditions at the end of life, and that it is a time to pass on traditions, share stories, and participate in traditional ceremonies. They also described cultural community practices around supporting community members through grieving. The importance of culture is illustrated in the quote below:

“The community will always bring you back to culture. You will need to adapt your service provision to maintain that cultural uniqueness. Each family is unique. They may be traditional and attend the Longhouse or they may be Christian and attend one of the many churches, or they may be a combination of both. Six Nations thought it was important to include the traditional Elders, healer and pastors in a team we could call upon as needed.” —Internal Health Care Provider

Internal health care providers described feeling honored to journey with their clients and felt gifted with their clients’ stories. They explained they found great meaning in their work and grew close to their clients and families. They acknowledged that it is more common and acceptable for health care providers to emotionally bond with their clients in the First Nations community as compared with outside. This is due to the close personal relationships among everyone in the community.

“Cause you say we’re a big reserve and we are, but we’re still all intertwined in some way. Like we may not be relatives, but we grew up, or they know our brother or whatever. But when somebody is dying and they need help, our community members will, well we’ll help each other.” —Community Member

At the outer edge of Figure 2 is the external caregiving network depicting the health care system outside the community (primarily non-Indigenous). This includes physician services, hospitals, home care and long-term care as well as other specialized services (e.g., PC services, cancer care and PC educators). Data indicated a strong social and cultural barrier exists for community members accessing the external caregiving network. External caregivers lack ongoing, committed, trusting relationships with the community and culturally respectful care practices. The boundary between the community and the external network is depicted as thick to represent this barrier. Supporting data are provided below:

“In the hospital, you got to get out at a certain time, certain number of people, but when you’re at home people can come and go in and out. People can sit there and sit with you for hours on end. That is one of the reasons people like being in their household.” —Elder/Knowledge Carrier

“When I am near death, wheel me outside. Let me smoke my pipe outside the long-term care facility. Don’t worry about the cold, I am dying. My physical being needs to hold the pipe (its last chance). Don’t maul my body! Give my family time. It doesn’t matter if you know the exact time of my death.” —Community Member

Overall, the assessments revealed that the communities had many strengths and assets that could assist in community members dying at home (e.g., dedicated health care providers and local services, strong natural helping networks, Indigenous understandings of death/dying, traditional caregiving practices).

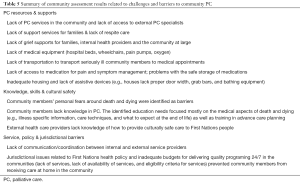

Challenges and barriers to community PC

The assessments also identified multiple challenges and barriers that would need to be addressed to better support PC in the communities. These are summarized in Table 5.

Full table

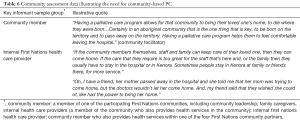

A strong theme emerging from the data was the need for increased PC services in the community, especially for physical care and pain and symptom management. Families that had cared for loved ones described feeling powerless and not adequately supported to bring a family member home; this impacted both the principal and internal caregiving networks (Figure 2). Communities were not resourced to provide services on evenings and weekends or to provide sufficient hours of care to people with advanced illness. Table 6 provides quotes illustrating the need for community-based PC.

Full table

In summary, the community assessments showed that, consistent with health promoting PC, community involvement and support of families at the end of life was traditional practice. A social and cultural model of care was already in place within the communities. While the social processes for supporting community members through death and dying were well established, the formalized PC services, supports and policies were lacking.

Section 2: Outcomes to guide development of PC programs in First Nations communities

A First Nations’ adaptation of Kelley’s community capacity development model

An early research outcome was adaption of Kelley’s community capacity development model to the First Nations culture and context (see Figure 3). Consistent with the original model, PC program development is a bottom-up process which occurs through sequential phases of growing community capacity. The adapted model included a new tree graphic that was created by the project participants in Six Nations of the Grand River Territory and was given to the EOLFN project to use in the project.

The graphic is infused with cultural meaning (see note, Figure 3). The adapted model includes modification of the language to be more familiar and accessible for community use. Two antecedent conditions of community readiness are added, namely, having sufficient community infrastructure (water, housing, transportation etc.) and having strong, consistent community leadership. Whole community collaboration replaces the focus only on health care providers. A new phase of development was added called “Grounding the Development in Community Values and Principles”. This emphasizes that the person, family, community and culture (social context) are foundational to the program development process in the First Nations’ adapted model.

This First Nations’ adaptation of the Kelley model describes each community’s incremental progress though the five phases of developing a PC program. Beginning at the bottom, each phase builds on the phase below, although work in each phase must continue (never ending). Program development takes time (months to years). The rate of progress will vary; communities can move forward or backward in the phases depending on their unique antecedent conditions and other situations happening within each community. Ultimately, the PC program becomes integrated into existing health services (e.g., Home and Community Care program, and is not a separate specialty service).

Once program guidelines are created, the program grows through implementing five processes: strengthening community relationships, building external linkages, providing PC in the community, promoting education and advocating for individuals and families. Growing the program happens from the inside out; external partners are engaged only after the community has created the program and identified what outside help they want and how they want it. The principles of local control and community empowerment are fundamental to success.

Four customized PC programs in First Nations communities

Through the research, each community developed a unique and customized PC program with guidance from their local PC Leadership Team (composed of Elders, Knowledge Carriers, community members, and local health care providers). The achievements of each community are summarized in Table 7. More detailed descriptions of the communities’ experiences are available in separate publications (47,49). Examples of two community program descriptions and a table summarizing how one community implemented the five phases of the model are included as supplementary files (Supplementary files 2-4).

Full table

The PC programs evolved differently in each community. Overarching keys to success were identified using comparative analysis and factors accounting for the variation among the communities; those are summarized in Table 8.

Full table

A workbook of resources to guide program development in First Nations communities

Through documenting and evaluating the PC program development in the four communities, “The Developing Palliative Care Programs in First Nations Communities Workbook” was created. The workbook, organized according to the First Nations’ adapted model, outlines the capacity development approach and provides practical resources developed in the four communities. There are resources to assess PC capacity in a community and, based on what already exists, to develop or enhance the programs and resources to better support people to live at home until the end of their lives. A summary of the workbook contents is available as a supplementary file to this article (Supplementary file 5). The workbook and resources are also published on an open access website (http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/).

Based on the activities of the researchers, a facilitator guide called “Supporting the Development of Palliative Care Programs in First Nations Communities” was created to guide external partners who participate in capacity development with First Nations communities (56). The guide summarizes the EOLFN capacity development approach and provides strategies appropriate at each phase of program development. The importance of cultural humility and the need for the “outsider” (external partner) to take direction from the community is emphasized. Partners can provide valuable mentorship, support, education and create opportunities for new linkages and resources.

Section 3: Outcomes to guide policy and planning

The need for supportive public policy

The research demonstrated the need for creating new public policy that: supports First Nations communities to undertake PC capacity development; enhances funding and resources to implement services; respects community control; and requires collaboration between First Nations, federal and provincial health care systems (51-54). There are currently barriers to collaboration between the federal and provincial health services, and jurisdictional confusion about the mandate to fund and provide PC (57). This research demonstrated the benefits of taking highly localized approaches to PC development, recognizing that needs and solutions are specific to place, context and culture. Programs that are locally developed, controlled and embedded in existing community social support networks are inherently culturally appropriate. partnerships between federal, provincial and First Nations governments are required.

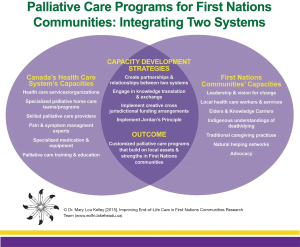

Policy development process: integrating the capacities of two systems

The guiding principle of two-eyed seeing articulated by Mi’kmaw Elders Albert and Murdena Marshall provided the research with an appropriate vision for policy development. Implementing this principle, one eye sees using Indigenous ways of knowing and the other sees using Western perspectives. Thus, two-eyed seeing is based on a “dynamic, changing, interaction and relational process which generates new ideas, understandings and information” (58,59). For PC, this approach meant integrating knowledge and resources from community and culture, with specialized PC knowledge and resources to support people with serious illness and their families to receive PC at home. It further emphasized that PC capacity development is the outcome of an emergent process to generate new knowledge. This policy making approach and capacity development strategies are illustrated in Figure 4.

Policy recommendations and guidelines for program development

Two policy documents were created based on this research. The first, called “Recommendations to Improve Quality and Access to Palliative Care in First Nations Communities” (60), includes four recommendations that are directed at the federal government who have constitutional responsibility to provide and fund First Nations health services. These recommendations could be implemented immediately though political will. For example, enhanced resources for PC can flow into the Home and Community Care Program already funded in First Nations communities. Funding levels for home care are insufficient to meet the needs of people with advanced chronic and terminal illness; program funding has not increased (except cost of living increases) since it was developed in 1999 (61).

The second document, called a “Framework to Guide Policy and Program Development for Palliative Care in First Nations Communities” (62), targets health care decision makers and program planners at three levels: the First Nations community, provincial health services responsible for PC services and federal health services responsible for First Nations health. It provides ten guidelines for PC program development in First Nations communities based on the principles of capacity development, equity and social justice. The guidelines call for respecting the integrity of each First Nations community, its unique philosophy, and cultural traditions. Delivering services should be done through teamwork/collaboration and partnerships (within the community and between the community and external health services). Consistent with the Indigenous First Nations’ model (Figure 3), the PC program provides services, advocacy and education for family and community members and education for the First Nations health care professionals.

Discussion

The following discussion highlights the contributions of this research for PC practice, policy and research. Limitations of the research are also acknowledged.

Contributions to practice and policy

It is well documented in the international literature that despite the growing need, First Nations people experience many barriers to accessing PC. The needs and barriers identified in the EOLFN research were consistent with those identified in an international literature review by Caxaj et al. The review concluded by identifying the following three priorities for providing Indigenous PC: (I) family centeredness throughout the PC process; (II) building local capacity to provide more relevant and culturally appropriate PC; and (III) flexibility and multi-sectoral partnerships to address the complexity of day-to-day needs for patients/families (6). The capacity development approach used in the EOLFN project created four community-based PC programs and addressed all those priorities. As a result, seriously ill community members had the choice to receive care in their community. While not all clients died at home, all received PC at home longer than before (47,49).

Through the capacity development process, communities created program models where internal community and external health and PC services worked together to support members in the First Nations community. Strategies such as journey mapping clarified roles and strengthened partnerships between community and external health care providers (46). Building on and reclaiming their historical and cultural traditions of family and community caregiving, the four First Nations communities involved in our research have demonstrated that they can mobilize their own capacity to provide PC. The communities have shared all their resources and learnings in the workbook that can be used by other First Nations communities across Canada to develop similar programs (63).

A unique contribution of the research was providing a practical example of how to do community capacity development in a place-based community with a distinct social and cultural context. The change process was grounded in the social and cultural characteristics of the community and built on local strengths and assets. The catalyst for change was a passionate and dedicated local health care provider who could mobilize community members. Unmet needs were identified internally by the community (not by the external health system) and community-led action was undertaken to address them. External health services reoriented to better support community care (better discharge planning, better communication and collaboration between internal and external health care providers, and increased cultural understanding by external providers). Community members successfully advocated for needed funding, medication and equipment to provide palliative home care. The role of the researchers was to support, mentor, educate, empower and organize—to provide structure around their process, and provide them resources and tools. The outcome was different in each community, as required to meet their unique needs.

The research also validated the Kelley model for use with First Nations communities. During the EOLFN research, an adaptation of the Kelley model was created to represent a culturally appropriate theory of change for First Nations communities (36). This First Nations application of the Kelley model illustrates that other unique Indigenous groups could adapt and use the Kelley model in their specific context. The model is intended to be adapted to local context.

This research provides an example of health promoting PC (33,64,65) where end of life is viewed from a social, cultural, and community lens. Consistent with health promotion strategies, the EOLFN project used public education, community engagement and development, policy development, and participatory methods of working. The PC programs created in the First Nations communities helped dying people avoid or delay accessing external services (harm reduction) and build on the positive, social and personal assets in communities.

The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion outlines that successful public health interventions require attention to strengthening community action, developing personal skills, creation of supportive policies and supportive environments, and reorienting health services. Three basic strategies are endorsed: advocate, enable, and mediate (66). An important contribution of the EOLFN research approach is illustrating how all the components of the Ottawa Charter can be implemented. Every one of these components was essential to achieving the desired outcome. In 2017, the Canadian federal government announced more home care funding for First Nations communities, including PC. Some provinces are now engaging more with First Nations communities regarding health services.

The EOLFN community capacity development approach has potential to be used in place-based contexts anywhere across geographies. It overcomes cultural differences by integrating PC into existing social networks and services. This research further illustrates the potential of the Kelley model for broader use since it guides communities to adapt and customize each phase of PC program development to their unique needs. The process is about building on local capacity, and the strengths that already exist in the community. The EOLFN research illustrates that the original Kelley model can (and should be) adapted by the population that it is going to use it.

Contribution to research

This research illustrates the benefits of PAR as a methodology to create culturally appropriate, community-based PC programs. PAR recognizes the expertise of First Nations community members and promotes integration of community values and practices into PC. Researchers and participants co-create knowledge through a reflective spiral of activity: identifying a problem, planning a change, acting and observing the process and consequences of the change, reflecting on these processes and consequences, and preplanning, acting, observing and reflecting (repeating the cycle) (44). PAR is particularly relevant to facilitating change and development as the research is embedded in social action. In PAR practice and policy are altered through the research (policy change, practice change, and research occur simultaneously).

PAR offers an appropriate methodology for health promoting PC research. Recently, Sallnow and colleagues proposed that, to advance the health promoting PC literature, participatory approaches are needed to complement the traditional approach to public health research which focuses on quantitative, epidemiological, and clinical research (67). The EOLFN research demonstrates the value of PAR methods for community capacity development in PC. PAR is particularly relevant to working with Indigenous communities because data required for the more traditional public health methodologies (e.g., longitudinal population-level PC data) are lacking for Indigenous populations in Canada. Further, ethical issues are high priority when conducting Indigenous health research and the PAR approach is consistent with guidelines created for national use in Canada (40,41).

Our findings also offer new learnings about the role and importance of place (internal and external caregiving networks), leadership, education and sense of community as keys to success. It also provides evidence of the important role of culture as an asset in capacity development. In addition, the research provided insights on the impact that community context (antecedent conditions) has on PC program development. While all communities implemented the same capacity development process and created a PC program, there were variations in their experience (Table 8); those comparative insights can inform further application of the model.

Limitations

There are two limitations to the research. First, the intent of the research was knowledge creation related to developing the PC programs rather than evaluation of program outcomes. Only two communities documented outcomes related to the number of clients and services provided, participant satisfaction and perceived benefits (47,49). The impact of the new program on quality of patient care is not known or how community care compared with usual care outside of the community. Second, this was case study research done in only four communities in Canada. The transferability of research results to other First Nations communities in Canada, or to Indigenous communities internationally, requires further examination. However, the solid theoretical foundation in the Kelley model strengthens the likelihood of theoretical generalizability (68).

Conclusions

This research contributes to the international literature on public health and PC in Indigenous communities. It also provides Canadian evidence of the benefits of community capacity development to create culturally appropriate PC programs. The research adds understanding of how Indigenous communities can mobilize to provide PC and illustrates the appropriateness of using the public health approach where end of life is viewed from a social, cultural and community lens. It also furthers our understanding of the keys to success for community capacity development.

Four First Nations communities developed PC programs that integrated their social and spiritual practices, local health services and specialized PC expertise. This approach, fully grounded in local culture and context, can be adapted to Indigenous communities elsewhere in Canada and internationally. A workbook of culturally appropriate resources was developed that provides resources for PC program development, direct care, PC education, and engaging external partners (63). Policy recommendations and a policy framework to guide PC program development in Indigenous communities were created (60,62). These resources are published on an open access website (www.eolfn.ca) for use by all interested Indigenous people and others.

Methodologically, this paper contributes to the public health and PC research agenda by demonstrating the achievements of PAR in strengthening community action to create PC programs, developing the personal skills of community health care providers and creating more supportive environments for people who wish to receive PC at home. PAR is a research tool that can be used for implementing health promoting PC across geographies and cultures. The Kelley model, adapted by First Nations communities, was validated for use to guide developing community capacity for PC. The model can now be adapted for use in other geographies and cultures.

File 1 Instruments used in the community assessments (survey and interview and focus group guides)

File 2 Palliative care program guidelines, example: Naotkamegwanning First Nation

File 3 Palliative care program guidelines, example: Six Nations of the Grand River Territory

File 4 Implementing the community development process—an overview of the process of Six Nations of the Grand River Territory

File 5 Developing palliative care programs in First Nations communities workbook summary.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Advisory Committees, Leadership, Elders, Knowledge Carriers and community members of the four participating First Nations communities without whose dedication this project could not have been done.

Funding: This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant #105885) with additional funding from Health Canada for creating the document, “Supporting the Development of Palliative Care Programs in First Nations Communities: A Guide for External Partners”. Dr. Mushquash’s involvement was partially supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The research was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Lakehead University (REB #020 10-11), McMaster University (REB #10-578), Six Nations of the Grand River Territory and the Chief and Councils of Fort William, Naotkamegwanning, and Peguis First Nations. All participants in the project provided informed consent.

References

- Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care: Based on National Principles and Norms of Practice. 2013. Available online: http://www.chpca.net/media/319547/norms-of-practice-eng-web.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Definition of Palliative Care. 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Johnston G, Vukic A, Parker S. Cultural understanding in the provision of supportive and palliative care: Perspectives in relation to an Indigenous population. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:61-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGrath CL. Issues influencing the provision of palliative care services to remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory. Aust J Rural Health 2000;8:47-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Indigenous palliative care. J Palliat Care 2010.26. [Special Issue].

- Caxaj CS, Schill K, Janke R. Priorities and challenges for a palliative approach to care for rural Indigenous populations: A scoping review. Health Soc Care Community 2018;26:e329-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada, Indigenous and Northern Affairs. First Nations People in Canada. Available online: https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng

- Government of Canada, Indigenous and Northern Affairs. First Nation Profiles Interactive Map. Available online: http://fnpim-cippn.aandc-aadnc.gc.ca/index-eng.html

- Prince H, Kelley ML. An integrative framework for conducting palliative care research with First Nations communities. J Palliat Care 2010;26:47-53. [PubMed]

- Lavoie JG, Forget EL, Browne AJ. Caught at the crossroad: First Nations, health care, and the legacy of the Indian act. Pimatisiwin 2010;8:83-100.

- Chiefs of Ontario. A Guide for First Nations in Ontario: Navigating the Non-Insured Health Benefits & Ontario Health Programs Benefits. 2013. Available online: http://www.chiefs-ofontario.org/sites/default/files/files/NIHB%20Guide%20Condensed%20Jan%2031%202013.pdf

- Duggleby W, Kuchera S., MacLeod R, et al. Indigenous people’s experiences at the end of life. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1721-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelley ML. Guest Editorial, An Indigenous issue: Why now? J Palliat Care 2010;26:5. [PubMed]

- Kelly L, Minty A. End-of-life issues for Aboriginal patients: a literature review. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:1459-65. [PubMed]

- Westlake Van Winkle N. End-of-life decision making in American Indian and Alaska native cultures. In: Braun KL, Pietsch JH, Blanchette PL. Cultural Issues in End-of-Life Decision Making. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc., 1999:127-44.

- McGrath P. ‘I don’t want to be in that big city; this is my country here’: Research findings on Aboriginal peoples’ preference to die at home. Aust J Rural Health 2007;15:264-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Brien AP, Bloomer MJ, McGrath P, et al. Considering Aboriginal palliative care models: the challenges for mainstream services. Rural Remote Health 2013;13:2339. [PubMed]

- Health Canada. Summative evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care. 2009. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/services/first-nations-inuit-health/reports-publications/health-care-services/summative-evaluation-first-nations-inuit-home-community-care.html

- DeCourtney CA, Jones K, Merriman MP, et al. Establishing a culturally sensitive palliative care program in rural Alaska native American communities. J Palliat Med 2003;6:501-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hotson KE, Macdonald SM, Martin BD. Understanding death and dying in select First Nations communities in northern Manitoba: issues of culture and remote service delivery in palliative care. Int J Circumpolar Health 2004;63:25-38. [PubMed]

- Prince H, Kelley ML. Palliative care in First Nations communities: the perspective and experiences of Aboriginal elders and the educational needs of their community caregivers. Thunder Bay, ON: Lakehead University, 2006.

- Rix EF, Barclay L, Stirling J, et al. ‘Beats the alternative but it messes up your life’: Aboriginal people’s experience of haemodialysis in rural Australia. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005945. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Habjan S, Prince H, Kelley ML. Caregiving for Elders in First Nations communities: Social system perspective on barriers and challenges. Can J Aging 2012;31:209-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGrath P. Aboriginal cultural practices on caring for the deceased person: Findings and recommendations. Int J Palliat Nurs 2007;13:418-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Houkamau CA, Sibley CG. The multi-dimensional model of Māori identity and cultural engagement. NZ J Psychol 2010;39:8-22.

- Moeke-Maxwell T, Nikora LW, Awekotuku NT. End-of-life care and Māori Whānau resilience. MAI Journal 2014;3:140-52.

- Decourtney CA, Branch PK, Morgan KM. Gathering information to develop palliative care programs for Alaska’s aboriginal peoples. J Palliat Care 2010;26:22-31. [PubMed]

- Kelley ML, Habjan S, Aegard J. Building capacity to provide palliative care in rural and remote communities: does education make a difference? J Palliat Care 2004;20:308-15. [PubMed]

- Hampton M, Baydala A, Bourassa C, et al. Completing the circle: Elders speak about end-of-life care with Aboriginal families in Canada. J Palliat Care 2010;26:6-14. [PubMed]

- Kelly L, Linkewich B, Cromarty H, et al. Palliative care of First Nations people: a qualitative study of bereaved family members. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:394-5.e7. Erratum in: Can Fam Physician 2009;55:590. [PubMed]

- Castleden H, Crooks VA, Hanlon N, et al. Providers' perceptions of Aboriginal palliative care in British Columbia's rural interior. Health Soc Care Community 2010;18:483-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hampton M, Baydala M, Drost C, et al. Bridging conventional Western health care practices with traditional Aboriginal approaches to end of life care: A dialogue between Aboriginal families and health care professionals. Can J Nurs Infromatics 2009;4:22-66.

- Abel J, Kellehear A. Palliative care reimagined: A needed shift. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:21-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norton BL, McLeroy KR, Burdine JN, et al. Community capacity: Concept, theory, and methods. In: Clementi RD, Crosby R, Kegler M. editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2002:194-227.

- Morgan P. Capacity and Capacity Development: Some Strategies. Hull, QC: Policy Branch, CIDA, 1998.

- Kelley ML. Developing rural communities’ capacity for palliative care: A conceptual model. J Palliat Care 2007;23:143-53. [PubMed]

- Crooks VA, Castleden H, Schuurman N, et al. Visioning for secondary palliative care service hubs in rural communities: a qualitative study from British Columbia’s interior. BMC Palliat Care 2009;8:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelley ML, Williams A, Sletmoen W, et al. Integrating research, practice, and policy in rural health: a case study of developing palliative care programs. In: Kulig JC, Williams A. editors. Rural Health: A Canadian Perspective. University of British Columbia Press, 2009:219-38.

- Robinson CA, Psut B, Bottorff JL, et al. Rural palliative care: A comprehensive review. J Palliat Med 2009;12:253-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. 2014 [Chapter 9: Research Involving First Nations, Inuit and Metis Peoples of Canada]. Available online: http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2-2014/TCPS_2_FINAL_Web.pdf

- First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP): The Path to First Nations Information Governance. Available online: http://fnigc.ca/sites/default/files/docs/ocap_path_to_fn_information_governance_en_final.pdf

- Yin R. Case study research: Design and methods. 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013.

- Webb C. Action research: Philosophy, methods and personal experiences. J Adv Nurs 1989;14:403-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kemmis S, McTaggart R. Participatory action research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2005.

- Brazil K. Issues of diversity: Participatory action research with Indigenous peoples. In: Hockley J, Froggatt K, Heimerl K. editors. Participatory Research in Palliative Care: Actions and Reflections. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Koski J, Kelley ML, Nadin S, et al. An Analysis of journey mapping to create a palliative care pathway in a Canadian First Nations community: Implications for service integration and policy development. Palliat Care 2017;10:1178224217719441. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fruch V, Monture L, Prince H, et al. Coming home to die: Six Nations of the Grand River Territory develops community-based palliative care. Int J Indig Health 2016;11:50-74. [Crossref]

- Prince H, Mushquash C, Kelley ML. Improving end-of-life care in First Nations communities: Outcomes of a participatory action research project. Psynopsis 2016;17.

- Nadin S, Crow M, Prince H, et al. Wiisokotaatiwin: Development and evaluation of a community-based palliative care program in Naotkamegwanning First Nation. Rural Remote Health. Available online: https://rrh.org.au/journal/early_abstract/4317

- Yin R. A (very) brief refresher on the case study method. In: Yin R. editor. Applications of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2012.

- Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities Research Team, Lakehead University. Fort William First Nation Community Needs Assessment Report. [Final Report]. 2008. Available online: http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/FWFN_CommunityReport_Final_July102013.pdf

- Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities Research Team, Lakehead University. Naotkamegwanning First Nation Community Needs Assessment. Report. [Final Report]. 2008. Available online: http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/project-results/reports

- Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities Research Team, Lakehead University. Peguis First Nation Community Needs Assessment Report. [Final Report]. 2008. Available online: http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/PFN_CommunityReport_Final_Oct2013.pdf

- Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities Research Team, Lakehead University. Six Nations of the Grand River Territory Community Needs Assessment Report. 2008. Available online: http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/SNGRT_CommunityReport_Final_May122013.pdf

- Abel J, Walter T, Carey LB, et al. Circles of care: should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:383-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prince H. Supporting the Development of Palliative Care Programs in First Nations Communities: A Guide for External Partners. Available online: http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca

- Provision of Palliative and End-of-Life Care Services to Ontario First Nations Communities: An Environmental Scan of Ontario Health Care Provider Organizations. 2013. Available online: http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Provision_of_Palliative_Care_to_Ontario_FN_Communities_April_2013_FINAL.pdf

- Bartlett C, Marshall M, Marshall A. Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J Environ Stud Sci 2012;2:331-40. [Crossref]

- Institute for Integrative Science & Health. Two-Eyed Seeing. Available online: http://www.integrativescience.ca/Principles/TwoEyedSeeing

- Recommendations to Improve Quality and Access to End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities: Policy Implications from the Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities research project. 2014. Available online: http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Recommendations_to_Improve_Quality_and_Access_to_EOL_Care_in_FN_Communities_December_1_2014_FINAL.pdf

- Health Canada. Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program 2008–2009 to 2011–2012. Evaluation Directorate, Health Canada and the Public Agency of Canada. 2013. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/accountability-performance-financial-reporting/evaluation-reports/evaluation-first-nations-inuit-home-community-care-program-2008-2009-2011-2012.html

- Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities Research Team, Lakehead University. A Framework to Guide Policy and Program Development for Palliative Care in First Nations Communities. 2015. Available online: http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Framework_to_Guide_Policy_and_Program_Development_for_PC_in_FN_Communities_January_16_FINAL.pdf

- Improving End-of-life Care First Nations Communities Research Team. Developing palliative care programs in First Nations communities: A workbook (Version 1). 2015, p.5. Available online: http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/develop-palliative-care-programs-workbook

- Kellehear A. Commentary: Public health approaches to palliative care – The progress so far. Prog Palliat Care 2016;24:36-8. [Crossref]

- Kellehear A. Compassionate Cities: Public Health and End-of-Life Care. London: Routledge, 2005.

- World Health Organization. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. 1986. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/health-promotion/population-health/ottawa-charter-health-promotion-international-conference-on-health-promotion/charter.pdf

- Sallnow L, Tishelman C, Lindqvist O, et al. Research in public health and end-of-life care: Building on the past and developing the new. Prog Palliat Care 2016;24:25-30. [Crossref]

- Yin R. Analytic Generalization. In: Mills AJ, Durepos G, Wiebe E. editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010:21-3.

- ML Kelley, Prince H, Nadin S, et al. The power to choose: the story of developing palliative care in four First Nations communities. Asvide 2018;5:442. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/24557