Healthy End of Life Project (HELP): a progress report on implementing community guidance on public health palliative care initiatives in Australia

Introduction

We often forget that palliative care began as a grass-roots community movement. Hospice programs came into being as local communities responded to people who in the sixties and seventies began to articulate their desire to change the way end of life care was provided (1-4). The health services of the day at best tolerated, and at worst opposed, these attempts to reform care of the dying. In most places, it took more than a decade for hospice services to be recognized by mainstream healthcare providers and included in government policy, planning and funding. But a consequence has been that hospice care—rebranded as palliative care—has simultaneously found a place within healthcare systems and been distanced from its roots in local communities (5).

One of the goals of mainstreaming was to make end of life care more accessible to the general population. Palliative care’s success in promoting its particular contribution to end of life care has led to a different access problem. Services now find themselves over-extended in responding to a growing demand for quality end of life care, and face an increasing death rate as baby-boomers enter old age. This growing pressure on professional services has led healthcare providers and policymakers alike to recognize that more responsibility for end of life care should be devolved, through a palliative approach, to primary care (6), and that communities must somehow be re-engaged in end of life care. The rationale for this is plain. Kellehear points out that: “the great majority of people who are living with cancer and other life limiting or terminal conditions spend their time with families, workmates and friends outside of any formal health care system. Most care during this time is informal (non-professional), but many people feel unprepared when such illnesses befall them or others. In many of our local communities we need to relearn the old ways of caring for one another—those persons who are dying and those left behind.” (7).

Contemporary end of life care policies thus identify a need to increase community capacity by developing sustainable skills, policies, structures, and resources that support members of a community in caring for each other at the end of life (8). However, the way end of life care has become so embedded in health services leads most people to assume that best-practice care is delivered by healthcare professionals, and hence the options for community engagement become focused around fund-raising activities and volunteer support of professional services. Such activities certainly involve interested community members in supporting end of life care, and raise community awareness of end of life programs; but it is debatable whether they increase community capacity to provide care, the goal articulated in end of life policies.

Rather, as Kellehear indicates, the care provided in community should complement care provided by professional services. To build community capacity we need to attend to those aspects of care that communities can provide but professional services cannot, such as long-term supportive relationships, practical neighborly assistance, shared activities that reinforce purpose and meaning, and compassionate presence during the long periods of waiting between encounters with formal health services (9). Further, to value this informal care we need to understand care in collaborative ways, as an activity in which formal and informal caregivers’ combine (10,11) to meet the diverse needs of people in the last years of their lives.

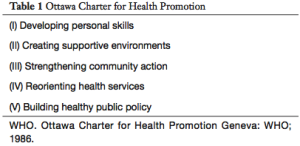

Public health provides a framework to conceptualize care in this way. Health is more than the absence of disease and disability (12). A fundamental requirement for health is a healthy environment. Health is created in communities that reflect the richness and diversity of human experience within their membership. Health is determined by a range of social factors, and strategies for health need to involve much more than providing ‘health services’ that focus on illness (13). Applying this public health understanding to end of life experience opens up a further goal of care beyond the needs-based focus of health service delivery: we’re invited to consider the nature of health in the last days of life, that is, how we might achieve a healthy end of life. And we’re provided with some tested strategic frameworks to adapt to end of life experience. The Ottawa Charter (14) (Table 1) provides a framework for creating health through participatory action in communities. It does not prescribe what is involved in ‘health’ beyond asserting that certain sorts of activities are required to create health and (by implication) that contradictory forms of action won’t do so. Similarly, a Healthy Settings (6) approach focuses on characteristics and values that support healthy action, including, preserving autonomy, supporting caring networks, nurturing compassion, and challenging policies and practices that constrain autonomy and choice. End of life applications of these core frameworks have been available for the better part of two decades. Ottawa Charter meets hospice care in Health Promoting Palliative Care (15), and Healthy Cities (16) meets end of life care in Compassionate Cities (17).

Full table

While the Compassionate Cities framework describes the settings in which end of life values and qualities might flourish, it provides only general guidance about how this approach might be implemented. As Abel and Kellehear (9) note, a key consideration for the compassionate communities movement is the challenge of mobilizing community assets and community capacity to their full potential. In what follows we describe the development of a public health approach, named the Healthy End of Life Project (HELP), that provides a comprehensive guide for building the community capacities and capabilities needed to form, maintain and sustain Compassionate Communities, and that is designed for local community use.

Methods

The enquiry was carried out in three phases, the third of which is continuing. The research question for the first phase was “What’s involved in building individual capability and community capacity for end of life care?” The question was explored in a pilot study undertaken in a community located in the Dandenong Ranges of Victoria, Australia. ‘The Hills’ community is formed by eleven small townships scattered across the region, separated by national parks and state forests. The townships engage in friendly competition stemming from strong attachment to their local identities, but are united in the face of recurring natural disasters such as bushfires. The resilience and collaboration that characterize ‘the Hills’ were expected to be assets for facilitating community development approaches to end of life care.

This phase investigated individual and community experiences of providing end of life care in ‘the Hills’ by exploring individual and community networks, mapping assets, interviewing local leaders (n=8), community development workers (n=6) and carers (n=6), attending community meetings (n=16) and leading a focus group. The study helped identify personal and community social networks that supported care, and identified specific barriers in mobilizing these networks to providing end of life care at home. These pilot findings were checked against other accounts found through collaborations and literature search, and criteria common to community development approaches across these contexts were identified.

The research question for the second phase was “How might a public health approach address these barriers and enablers to building community capacity?” To answer this, we drew upon the community capacity building literature in general, and the public health end of life literature in particular, to design a strategy named HELP. We used as an organizing framework for HELP, the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (14), a public health standard for shaping and creating health through participatory action. The Charter provides an evidence-based systemic framework, and is already widely used in health promoting palliative care (15).

HELP is now entering its third year of development and implementation. The third phase of enquiry continues as the project is implemented and evaluated in a number of locations and contexts, including at the original pilot site. An evaluation framework has been set up, however outlining it in detail here is beyond the scope of this article.

Results

Phase one identified four themes that need to be addressed by any model intending to implement a public health approach to end of life care.

Social norms can be unhelpful

One of the most significant findings of this study was the reluctance of carers to accept help when it was offered by family, friends and neighbors. This was the case almost without exception, even when the carer had regular access to family members and had a healthy network of friends. Declining offers of support was an instinctive response, made without considering the merit or value of the proposed offer of assistance, and irrespective of whether support was needed. Three common reasons for refusing offers of help were: (I) the desire not to be a burden, (II) dying is a private matter, (III) not coping (defined as needing support) was viewed as socially unacceptable.

Equally problematic was that asking for help was not seen as an option. None of the participant carers reported asking for assistance from their existing support networks. Asking for increased support from services was more acceptable that asking for help from family, friends and neighbors. When Beth’s husband died at home, she expressed relief that the care period was relatively short; “I couldn’t have coped any longer”. Beth had two sons, living locally, willing to increase their level of support, and was a 30-year member of a local choir which met for practice and performances three times per week. When questioned why she didn’t reach out to her friends in the choir and ask for help during the care period she replied: “It never occurred to me to ask them…anyway, dying is a private matter, and you don’t want to ask people to do that—don’t you think?” Researcher: what would you do if one of the choir members asked you for support to care for her dying husband? “I’d do it in a heartbeat…I’d do anything to help them…we’re like family.” (Beth, 78).

At the monthly community meetings in the Neighborhood House, twenty interested locals, many of them carers, began to describe their experience of caring for a loved one who died at home in ways that included a shift in thinking. One younger woman, Amy, who cared for her new husband (they were recently married), while he died of cancer at home expressed her regret: “I was guilty of that (refusing to accept help). I was newly married and I wanted to cope with everything, and I thought I should be able to cope with it, and was worried what people would think of me. Now, when I think of how much time I spent vacuuming and cleaning so the house was clean for the palliative care nurses and the other services, I regret it. I could have spent more time with Mick. I don’t want other people to do what I did.” (Amy, 35).

Amy was well connected to her community through weekly participation in her local church. Weekly offers of help were extended, most of which she refused.

These findings raise important questions about the role of social networks within person-centered assessment and supportive intervention. That is, does the social support network of an individual need to be enhanced (increased in size), or unlocked (sufficient networks exist, but they are not being drawn upon), and how do we unlock individual and community support networks and, for those with few networks, where can social support be found?

Social interactions can undermine community capacity

We found strong evidence in ‘the Hills’ of people’s willingness to help each other in compassionate and practical ways. When it came to end of life care, however, not knowing what kind of assistance to offer, or how to offer it, resulted in awkward social interactions in which gestures of support were nearly always refused. Sometimes, as one participant pointed out “the gesture itself can be enough—knowing a friend is willing to help you”, but it’s more likely to only be ‘enough’ when support is not actually required. Another participant warned, “people will only ask you three times (if you need a hand), then they’ll stop asking you”. When repeated offers are met with repeated refusals, those offering support are likely to feel that they are intruding, assume assistance is not required, or feel personally excluded. Georgina, a local community development worker, and a past carer of her deceased husband shared her experience:

“When someone offered to help out, I felt bad saying no, sending them away thinking they had nothing to offer, so I developed a list of all the things that would be useful for me, you know, everything, bringing the bins in, attending to William’s beloved garden, organising firewood, shopping…and that made them feel involved, it was important to them to help us out and I couldn’t send them away thinking they had nothing to offer…they loved William and wanted to do something for him.” (Georgina, 74).

That is, these unhelpful social norms and social interactions can lead to adverse outcomes. In declining offers from people willing to provide support, not only do we deprive ourselves of valuable practical and emotional support, we simultaneously discard important opportunities to build individual skills and community capacity to care for each other during times of illness, dying, death and in bereavement.

Vulnerability can be engaged constructively

A recurring theme in community discussion was ways of identifying local residents in need of support. It was agreed that ‘self-identification’, disclosing a need for support, is more efficient than relying on local systems to detect those requiring support. That is, the social norm to be encouraged and endorsed by citizens is to ask for help when you need it. This requires an internal shift in the way we perceive ourselves and relate to others. What self-identification asks of us is to engage constructively with our vulnerability. For most of us, this is an uncomfortable and unwelcome shift away from independence and control. One way of maintaining autonomy through periods of vulnerability is to learn to accept our interdependence with others, a skill often first learned through providing support to others (18). For many, this is a new and challenging way of approaching the social isolation and deterioration often associated with illness, dying, grief and caring. In community meetings, participants started working with each other and with their respective networks to challenge and change personal values and the local community culture (social norms). In a community meeting Janine remarked: “my friend is struggling to care for her husband, she’s exhausted and teary, but she won’t accept help from anyone. She’s very proud. What I’m finding is that this isn’t a one-off conversation, I have to keep talking about it (asking for and accepting help) every time we catch up; it’s starting to sink in. She’s starting to see that there’s another way that she can go about this, and a way she can still get her needs met while caring for John, and for the first-time last week, she let me vacuum her house – but I told her it was a new vacuum cleaner and I needed to try it out! (Laughing..).” (Janine, 67).

Community culture needs to be collaborative

Participants agreed that seeing dying, death and bereavement as a private matter undermined initiatives to improve informal social care at the end of life. They also agreed that for end of life care to be viewed as ‘everybody’s business’ (19) a ‘collaborative community culture’ is needed, and that this should be promoted as a social norm. A social norm is “a generally accepted standard of behavior within a society, community, or group” (20) or “individuals’ perceptions about which attitudes and behaviors are typical or desirable in their community” (21). Participants suggested that common spaces such as schools, community houses, arts and cultural community organizations, and opportunity shops should be seen as assets that encourage social connection and facilitate social interaction that contributes to a community’s capacity to provide end of life care.

A key concern was the current invisibility of end of life matters in the community. Participants agreed that awareness should be incorporated in community development initiatives. Ideally, a two- pronged approach that focused on building end of life matters into existing networks as well identifying gaps and developing new initiatives that respond to local community needs would be used.

These findings are consistent with studies and observations made in other places. Abel and Kellehear (22) suggest that a barrier to network development is that offers of help are often turned way. More frequently studies emphasize the need to work at maintaining connection (23) but do not make explicit the barriers we have identified in this study. Most community development programs, not merely those addressing end of life issues, aim to promote and nurture social capital, described as trust, empathy and cooperation to promote well-being (9). The importance of trust for supporting a norm of reciprocity—mutual help—is emphasized by Lewis who suggest this ‘requires exploration in the palliative care population, as trust in particular was of primary importance in informal caregiving’ (24).

That social attitudes to receiving help may be a barrier to building collaborative communities has profound implications for implementing public health approaches, such as compassionate communities. To be effective, any public health practice model must attempt to modify these social norms.

Our findings in the first phase of the study suggest that the goals of a public health approach should be to create sustainable community environments with the capacity to engage in end of life discussion, support and practical care, whilst developing community norms that ensure citizens know about and can draw upon these assets when needed. While our findings arose from a particular community context, we wanted to develop a framework that could be applied in other settings and communities, and provide evidence-based resources that would enable community-driven work. We were also aware that concepts like developing individual capability, generating community capacity and changing unhelpful social norms need to be grounded in concrete examples of achievable activities. The what (outcomes emerging in the community) will take care of itself if the why (reasons motivating behavior change) and the how (acting in new and constructive ways) are simple and implementable.

Another criterion we took from our participants is that public conversations on issues relating to death, dying, loss and bereavement should partner with and draw upon existing community platforms, and at the same time create a community care network with capacity to support local residents, their families and carers, who wish to die at home. This combination not only mobilizes community capacity but also generates individual capability. Both are needed. Individual capability without public messages about shifting community culture limits the growth of collective action, while community awareness alone will not necessarily translate into practical caring networks that support home-based dying. These targeted strategies together serve to unlock the potential of a compassionate community, and also provide a range of different roles through which citizens can participate:

“We had locals who wanted to provide personal caring, but it didn’t lead to community change. Many were introverts and weren’t comfortable with speaking at and organising community events, so it eventually died off (pardon the pun!). When we all got together, it was also a real downer, there was no fun in volunteering for this all the time. We needed something fun to do as well, like organising local events, getting together to brainstorm creative ideas and plan. You need different roles for different people, and both sustain each other, and we needed something to celebrate as well!” (Karyn, 59).

Equally important for the successful implementation of public health palliative care approaches was guidance from evidence-based community development strategies, and this led us into phase two of the project. Community development can appear simple, yet small but crucial errors frequently impede progress. Providing guidance can assist community members to avoid common mistakes so that community resources are used efficiently. In particular, it is essential that any community development project is systemic, hence our use of the Ottawa Charter, which requires community action to address all five areas, as working on one or two areas alone will not produce sustainable change.

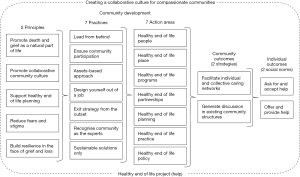

Our strategic responses to the key themes identified and reified in phase one, drawing upon public health evidence and insights, led us to develop a project we have called HELP (refer to Figure 1). The name indicates our intention to (I) promote health in end of life care and (II) to modify social norms around offering and accepting help.

HELP; offering & providing, asking & accepting help

The project aims to identify and build on local values and structures (community capacities) that will form, maintain and sustain a compassionate community. Such a community will be able to work cooperatively with carers, family, friends and neighbors to support residents who wish to receive end-of-life care in their home, or other community settings.

HELP guides communities on how they can create a framework for community members wanting to achieve the Compassionate Communities goal of “acting in new or constructive ways towards each other to improve their own capacity for end-of-life care” (17). HELP recognizes that local initiatives need to be shaped by community resources, assets, infrastructure, values and leadership, and that the new and constructive ways are collaborative. Horsfall, Noonan and Leonard (23) note that genuine community development and community capacity building cultivates and sustains a rich source of locally derived knowledge and skills, by presenting people with opportunities to learn and grow.

The unique traits, resources, and demographic of the geographically and culturally defined communities are taken into account by asset-based community development strategies, and the significance of one’s own place and community as a fundamental part of the dying person’s experience is acknowledged (11).

Two social norms

HELP aims to change two linked social norms that reduce the effectiveness of community development programs at the end of life: (I) despite their willingness to do so, people didn’t know what to offer or how to offer help and (II) carers automatically declined offers of help, despite needing it, and often despite having viable social networks. To create a collaborative culture that attends to local end of life care needs, the project is designed to:

- Shift the dominant culture from one where members instinctively decline help from personal and community networks toward one that not only provides but also ‘asks for and accepts help’;

- At the same time reinforce and encourage a community culture that is confident and capable of ‘offering and providing help’.

Two key strategies

The framework uses established community development strategies to build end of life capacity and capability in two strategic ways:

- By generating, through existing community structures, partnerships, forums and events, collective discussion and information sharing on the role of community at the end of life;

- By facilitating the development of social networks that are capable of responding to individual and collective end-of-life care needs in the community.

Five healthy end of life principles

Five principles underpin the activities of HELP to support communities in remaining focused on the changes they seek.

- Promote death and grief as a natural part of life;

- Promote a collaborative culture for community support;

- Support individual and community healthy planning for end of life;

- Reduce fears and stigma associated with illness and death;

- Build individual and collective resilience in the face of grief and loss.

These principles are closely aligned with health promoting approaches to palliative care (15,25).

Seven areas for community-driven action

HELP identifies a set of core health promotion strategies to provide practical guidance in creating collaborative caring at the end of life in communities. These areas for community-driven action are based on the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (14). The charter asserts that for population impact, working across all areas is important (Table 1). Working in one area alone will not produce sustainable change in community beliefs and practices. It’s evident that the 7 Ps of the HELP framework address the domains indicated by the Ottawa Charter.

- Healthy End of Life PEOPLE—identify, engage and support local people who are willing and capable of enabling and encouraging the community to shift to a sustainable collaborative culture for end of life care;

- Healthy End of Life PLACE—place-based approaches incorporate end-of-life support into existing social and community structures and settings to meet local need. Community members want to remain connected to the people, places and possessions that are important to them;

- Healthy End of Life PROGRAMS—design creative community initiatives based on local strengths and interests. Community members can be creative and imaginative with programs and have fun with their collaborations, in turn invoking curiosity and promoting interesting public dialogue;

- Healthy End of Life PARTNERSHIPS—develop local solutions through creative collaborations between community health and social organizations and individuals. Partnerships build sustainable community capacity, and are crucial to successful community development programs;

- Healthy End of Life PLANNING—coordinate local responses that aim to overcome structural barriers, change community culture and improve individual healthy end of life planning. End of life care planning in communities has been categorized in two areas for HELP:

- Community level: planning includes strategic plans in community organizations, collaborations with local health services, local government planning, township planning (public bereavement initiatives) and strategic collaborations that address barriers to end-of-life care being provided in the community, such as access to medical services and social support.

- Individual Level: initiatives that support local people to plan for and mobilize personal and community supports that meet end of life wishes. Such plans go beyond the more usual formal ‘care plans’ that itemize the care to be performed by paid professionals, and rarely include the carer, let alone any plan for assistance from the carer’s social network (26).

- Healthy End of Life POLICY - insert healthy end-of-life principles into existing and new policies alike, and remove unhelpful policies that undermine good outcomes in end of life care. Policy settings include local government, community health services, primary health and medical practitioners and community service organizations.

- Healthy End of Life PRACTICE - develop local initiatives that promote healthy end-of-life community practice. Work in this area includes practical support for dying people and their carers, home-based and community funerals and healthy bereavement support.

Seven community development practices

It is essential that community development practices are congruent with the goals and values they promote. In discussing the scale at which you engage community on new health and social issues, Craig, who has two decades of qualified health and arts-based community development expertise explains: “..some of the key things that I’ve learnt from working in the community over time is the scale at which you do things. We’ve always found, consistently, that trying to work intensively with a small group has a far greater outcome than trying to work broadly with a really large group. It’s best to let it grow organically, in its own time, especially with a topic such as death. I think we should start small and in-depth. And then it will grow from there.”

The following community development practices represent a stance that leads to successful outcomes (27), and should underpin the seven areas for community-driven action areas outlined above. The acronym ‘LEADERS’ has been used to promote recall.

- Lead from behind—enable others through coaching, mentoring and encouragement. Paid workers should avoid tasks that can be undertaken by community members, and initiatives taken should not increase dependency on professionals;

- Ensure community participation from the outset, and from all parts of the community—particular efforts should be made to engage citizens who are often excluded from community initiatives, such as people living with physical and intellectual disabilities, people with mental health issues, homeless people, newly settled people, culturally and linguistically diverse and indigenous people;

- Asset-based approach—build on existing strengths of the community. Asset-based community mapping is the first step in HELP, identifying ways end of life care is already provided, and canvassing other assets that could contribute to improving local end of life care. The process of mapping itself raises awareness, reframes perceptions of end of life issues, and generates a local repository of community supports and services for residents to access. Assets found might include service clubs, faith groups, country fire authorities, local businesses and neighborhood houses, to name but a few. Assets can be structural, cultural, economic, human and services. HELP resources include an assets mapping tool;

- Design yourself out of a job—in every step, every aspect and every decision. Decisions should be made by the community wherever possible;

- Exit strategy designed from the outset—the first step in planning is to incorporate participatory approaches that will encourage community ownership, particularly through developing creative partnerships that will sustain development;

- Recognize community as experts—communities should encourage leadership and have confidence in their capacity to respond effectively to local issues. Professionals need to be reminded of community members’ local knowledge and capacity to generate tailored solutions based on their shared wisdom;

- Sustainability—ensure sustainable outcomes by generating and supporting long term solutions. Only start what the community can finish.

Prospective study and evaluation

Interest from a range of people and places from conference presentations and word of mouth means that HELP will be implemented in a variety of Australian contexts, including a specialist community palliative care services, palliative and other volunteering programs, a cluster of neighborhood houses, local government programs and a community health hub in 2018. This will allow us to test the adaptability of the project, and enrich the range of resources that support it.

Evaluating the effectiveness of HELP as a public health palliative care intervention across these diverse settings forms phase three of the study. We are interested in studying the relationships between formal and informal networks through a specific strategy designed and promoted within the HELP framework, as well as observing changes in both measures (quantity and reach) and dimensions (quality and penetration) attributed to project implementation. Attention will be paid to the role of health services in developing compassionate communities through implementing HELP, with a particular focus on organizational structures that support network enhancement and informal care networks. Measures of end of life capacity in organizations, community groups and individuals will be studied, as well as monitoring the incidence of home-based end of life care and dying in locations where HELP is implemented. A Realist Evaluation approach, using mixed methods within a Stepped Wedge Design (28), and Social Network Analysis (29), has been developed for the evaluation. Measures of community (30-32) and organizational (33) capacity building will be applied, and shifts in social norms analyzed. Evaluation will inform further collaborative development of the project and resources.

Discussion

‘HELP; asking and accepting, offering and providing help’ contributes to the ‘compassionate communities’ movement by providing a framework and associated resources that can be used by community members as a practical guide to implementation. It illustrates how individuals and communities can act in new and constructive ways to cooperatively generate pathways that support caring at end of life in community and home-based settings. It fills a gap in the public health palliative care field by supporting self-initiated, or supported facilitation, of end of life care by members of local communities. The framework does not dictate the desires and agenda of community members, but facilitates choice, and ensures that practice continually draws from the growing body of evidence for public health approaches to palliative care.

Partnerships with palliative care, health services and other sectors are encouraged in the project to ensure “the myriad and diverse social epidemiology of ageing, dying, death, loss and caregiving” (34) is taken into account. A collaborative culture includes those services and organizations that are important to the end of life health of a community, but the role of health services in compassionate communities, while crucial, will be put into perspective as communities explore end of life as a social event, not just an event primarily managed by health services.

Conclusions

The substantive outcome of this enquiry is ‘HELP; offering and providing, asking and accepting help’. The project includes a practical suite of resources to guide communities to shift the local culture to one where end of life is seen as a collaborative and collective effort for citizens, community networks, structures and organizations.

We invite interested communities, organizations and services to use HELP to support the facilitation of compassionate communities in your local area. HELP resources are available on our Unit’s website, and proposals for collaborative evaluation projects are most welcome. Please contact Andrea Grindrod at a.grindrod@latrobe.edu.au for further information.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and contribution of the community organizations involved in the research; Burrinja Cultural Centre, Dandenong Ranges Music Council and Yarra Ranges Council; the support of Wendy Dagher, and research students Rachel Soh, Lauren Joy Baxter, and Elizabeth Truc Le for their project work. The La Trobe University Palliative Care Unit acknowledges ongoing funding support from the Victorian State Government Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: Approval for ethics for phase one of the study was provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee of La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia (No. S16-110).

References

- Hinton J. Dying. 2nd ed. Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin Books, 1967.

- Kübler-Ross E. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

- Lamerton R. Care of the dying. London: Priory Press, 1973.

- Stoddard S. The hospice movement: A better way of caring for the dying. London: Jonathan Cape, 1979.

- Rumbold B. Implications of mainstreaming hospice into palliative care services. In: Parker JM, Aranda S, editors. Palliative care: Explorations and challenges. Sydney: MacLennan & Petty, 1998:24-34.

- Kristjanson LJ, Toye C, Dawson S. New dimensions in palliative care: A palliative approach to neurodegenerative disease and final illness in older people. Med J Aust 2003;179:S41-3. [PubMed]

- Kellehear A. Newsletter: Hume Regional Palliative Care Service. Wangaratta, Victoria, Australia. 2005.

- Abel J, Walter T, Carey LB, et al. Circles of care: Should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:383-8. [PubMed]

- Abel J, Sallnow L, Murray S, et al. Each community is prepared to help: Community development in end of life care - guidance in ambition six. UK2016.

- Horsfall D, Leonard R, Noonan K, et al. Working together–apart: Exploring the relationships between formal and informal care networks for people dying at home. Progress in Palliative Care 2013;21:331-6. [Crossref]

- Horsfall D, Yardley A, Leonard R, et al. End of life at home: Co-creating an ecology of care. Sydney, Australia: Western Sydney University; 2015.

- WHO. Constitution of WHO: Principles. 1948. Available online: http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/. Accessed 15 December 2017.

- Lang T, Rayner G. Ecological public health: the 21st century's big idea? An essay by Tim Lang and Geof Rayner. BMJ 2012;345:e5466. [Crossref]

- WHO. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. WHO, Geneva. 1986. Available online: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/. Accessed 10 July 2017.

- Kellehear A. Health-Promoting Palliative Care: Developing a social model for practice. Mortality 1999;4:75-82. [Crossref]

- De Leeuw E, Tsouros AD, Dyakova M, et al. Healthy cities: Promoting health and equity - evidence for local policy and practice: Summary evaluation of Phase V of the WHO European Healthy Cities Network. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2014.

- Kellehear A. Compassionate cities: Public health and end-of-life care. London: Routledge, 2005.

- Kellehear A, Young B. Resilient communities. In: Monroe B, Oliviere D, editors. Resilience in palliative care. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007:223-38.

- Kellehear A. Compassionate communities: End-of-life care as everyone’s responsibility. QJM 2013;106:1071-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colman AM. A dictionary of psychology. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Paluck EL, Ball L. Social norms marketing aimed at gender based violence: A literature review and critical assessment. 2010.

- Abel J, Kellehear A. Palliative care reimagined: a needed shift. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:21-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horsfall D, Noonan K, Leonard R. Bringing our dying home: How caring for someone at end of life builds social capital and develops compassionate communities. Health Sociol Rev 2012;21:373-82. [Crossref]

- Lewis JM, DiGiacomo M, Luckett T, et al. A social capital framework for palliative care: Supporting health and well-being for people with life-limiting illness and their carers through social relations and networks. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:92-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lloyd L. Dying in old age: Promoting well-being at the end of life. Mortality 2000;5:171-88. [Crossref]

- Abel J, Bowra J, Walter T, et al. Compassionate community networks: Supporting home dying. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011;1:129-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grindrod A, Rumbold B, Dagher WJ. Evaluation of the Palliative Care Victoria community capacity building volunteer project. La Trobe University, 2015.

- Spiegelman D. Evaluating public health interventions: 2. Stepping up to routine public health evaluation with the Stepped Wedge Design. Am J Public Health 2016;106:453-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borgatti SP, Everett M, Johnson JC. Analyzing social networks. London: SAGE, 2013.

- Labonte R, Laverack G. Capacity building in health promotion, Part 1: for whom? And for what purpose? Crit Public Health 2001;11:111-27. [Crossref]

- Labonte R, Laverack G. Capacity building in health promotion, part 2: Whose use? And with what measurement? Crit Public Health 2001;11:136-8.

- Liberato SC, Brimblecombe J, Ritchie J, et al. Measuring capacity building in communities: a review of the literature. BMC Public Health 2011;11:850. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crisp BR, Swerissen H, Duckett SJ. Four approaches to capacity building in health: Consequences for measurement and accountability. Health Promotion International 2000;15:99-107. [Crossref]

- Kellehear A. The Compassionate City Charter: Inviting the cultural and social sectors into end of life care. In: Wegleitner K, Heimerl K, editors. Compassionate Communities: Case studies from Britain and Europe. Florence: Taylor and Francis, 2015.