The Portuguese versions of the This Is ME Questionnaire and the Patient Dignity Question: tools for understanding and supporting personhood in clinical care

Introduction

Modern medicine can sometimes be impersonal and routinized, with insufficient attention being paid to issues of patient personhood (1-4). This may be caused by mounting time pressures on health care professionals (HCPs) and a focus on delivering appropriate evidence-based care. Potential consequences include patients perceiving a lack of caring and becoming reluctant to trust the HCP. Such poor patient/HCP relationships may potentially contribute to missed diagnoses, compromised patient safety and poor overall quality of care (5-8). Consequently, patients and families are more likely to feel that their real concerns have not been heard, acknowledged or addressed, increasing the likelihood of complaints or even litigation (9-12). Clinicians may attempt to disengage from the caring facets of medicine, as a means of protecting themselves from emotionally painful aspects of attending to seriously ill patients. This emotional stance can accompany HCP burnout and clinical ineffectiveness (13,14). The anxiety of entering into conversations regarding personhood may be rationalized on the basis of it taking “too long”, detailing patient responses being too onerous, or it being emotionally evocative for patients and HCP alike (15,16).

Dignity and its multiple dimensions have always been central within the patient healthcare provider relationship. Dignity implies seeing people in terms of who they are rather than exclusively in terms of their medical ailments. In contemporary patient care, the concept of dignity is imperative (17) as a means of shifting the culture of care from one dominated by patienthood to one that is inclusive of personhood.

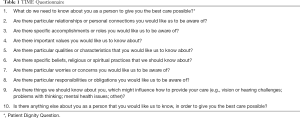

To understand and promote patient dignity, Chochinov et al. developed a single item tool designed to probe patient personhood, the Patient Dignity Question (PDQ)—“What do I need to know about you as a person to give you the best care possible?” (18). The PDQ is as an effective clinical tool to elicit dimensions of personhood. In a cross-sectional study in Canada, 93% of patients reported feeling the information obtained by the PDQ was important for HCP to know; and 99% would recommend it to others; 90% of HCP indicated they learned something new about the patients they cared for and 59% indicated the PDQ influenced their degree of empathy. Based on primary themes that emerged from the free text responses to the PDQ, the same team developed a set of items that were put together in the “THIS IS ME” (TIME) Questionnaire (19). The effectiveness of TIME in eliciting personhood and enhancing dignity was studied amongst residents and HCPs within six nursing homes in Canada. All residents indicated the resulting summary from TIME was accurate; 94% stated that they wanted to receive a copy of it; 92% indicated they would recommend TIME to others and 72% wanted a copy of the TIME summary placed in their medical chart. Ninety percent HCP agreed they had learned something new from TIME; and that TIME influenced their attitude, care, respect, empathy/compassion, sense of connectedness, as well as personal satisfaction in providing care (19).

The TIME/PDQ questionnaire is largely based on the empirical model of dignity in the terminally ill. While dignity is typically understood as meaning “the state or quality of being worthy of honor or respect” (20), the model based on qualitative input from terminally ill patients illustrates that there are multiple dimensions of end-of-life experience that can support or undermine patients’ sense of dignity (21). These include illness related factors (things that are directly mediated by the underlying condition itself), the dignity conserving repertoire (characteristics and practices which individuals can employ or invoke in the service of preserving dignity) and the social dignity inventory (that is, how dignity can be affected by the actions, demeanor and the relationships one has with others). It was on the basis of these themes and sub-themes that the TIME questionnaire was developed. Another study explaining the construct of dignity reported that “how patients experience themselves to be seen” was the most ardent predictor of sense of dignity (22). This sense of affirmation of personhood, typically defined as “the quality of condition of being an individual” (23) lies in contrast to how physical dimensions of end-of-life experience tend to predominate how patienthood is characterized. The PDQ was developed as a direct response to that characterization, providing patients opportunities to disclose information pertaining to relationships, accomplishments, roles, values, beliefs, etc. and how such inquiry might inform how HCP deliver care to those approaching end-of-life.

To the best of our knowledge, TIME is the only instrument that specifically addresses personhood. The availability of TIME in other languages would likely enhance patient care internationally and heighten an understanding of specificities of personhood. For this reason, we conducted a study aiming to translate and validate this personhood instrument to European Portuguese, which also includes the PDQ (as the initial question within TIME). The validity of the TIME Questionnaire was assessed using a three-stage research design: (I) translation and backtranslation, including the collaboration of an expert panel; (II) data collection using non-institutionalized active elderly; and (III) a final expert panel consultation (that included three additional experts to the initial panel).

Methods

The measure under study

Each eligible and willing participant is introduced to TIME (Table 1), which consists of a 10-item questionnaire designed to understand each individual as a person. While TIME was originally designed for self-administration, we tested the feasibility of reading the questions and writing down responses, verbatim and/or audio recording their responses. After introducing the study, an initial conversation is facilitated using TIME, based on what people feel comfortable sharing about their personhood. Typed summaries are then assembled based on their response. Within 24 hours, the clinician or researcher will return to confirm the accuracy of the contents of the TIME summary. Any erroneous or missing details are corrected until the participant is fully satisfied and considers the summary an accurate reflection of personhood.

In routine clinical care, TIME can be administered by any HCP caring for the patient. After introducing the questionnaire, patients are invited to write down their answers. If they decline writing, they can record the answers to a tape recorder. In the 24 hours after the interview the final summary is handed over to confirm its accuracy in capturing personhood.

Full table

Translation procedure

The process aimed at semantic and linguistic equivalence between the original and Portuguese versions, utilizing forward translation and back translation. The permission for translation was obtained in advance from the original authors. The first step was the independent forward translation from the English version into European Portuguese by a bilingual native Portuguese expert panel (three physicians, one psychologist and one bioethics professor, all with expertise in palliative care, two with additional knowledge in narrative medicine and legacy). The individual translations were returned to two bilingual researchers, who then created a consensus version. The preliminary forward translated version was subsequently passed on to an external bilingual translator who blindly back translated the forward translation back to English. The back translated version was compared with the original version by the first author (M Julião), who settled disagreements with the back translator. The back translated version was sent to TIME’s original authors (HM Chochinov), who confirmed the accuracy of the back translated version.

Data collection

Between June and October 2017, non-institutionalized active elderly (students and teachers from a Senior University of Gondomar, Portugal) were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) aged 50 or older; (II) ability to provide written informed consent; (III) native Portuguese speaker. Subsequently, the researchers verified eligibility, obtained the informed consent and sociodemographic data. Next, the study protocol and the TIME questionnaire [Questionário Este Sou EU (ESEU)], were introduced by the principal investigator and each participant received a printed ESEU questionnaire to take home to read and think about the answers they would feel most comfortable in sharing with the researcher.

Once participants read the ESEU’s questions, they would come to a first interview and comment on item ambiguity and provide responses they would feel comfortable sharing with others by way of an ESEU summary. In this interview the information given by each participant after responding to ESEU was clarified in order for the researcher to create the ESEU summary. Each participant also completed a feedback questionnaire, which included items rating clarity, content (i.e., relevance) and response time, rated on a Likert scale: 1 “strongly disagree”–7 “strongly agree” (Table 2).

After completing the ESEU summary, the principal investigator invited each participant to a second interview to deliver the summary and confirm its accuracy; any errors or missing details were corrected. Participants were asked to complete a second feedback questionnaire on their perceptions and effectiveness of ESEU, rated on a Likert scale: 1 “strongly disagree”—7 “strongly agree” (Table 2). This was adapted from Pan et al. (19).

Full table

Final expert panel consult

The ESEU’s Portuguese version was sent to the expert review committee to provide feedback on the final Portuguese ESEU version regarding the following: (I) approval of the final ESEU version; (II) belief that ESEU captured fundamental dimensions of personhood (III) clarity; and (IV) comprehensibility (rated in a Likert scale: 1 “strongly disagree”–5 “strongly agree”). Final consensus was set at 80% agreement between expert opinions. Further feedback was sought in order to strengthen the face validity process, so the authors invited a second expert panel consisting of three clinicians with expertise in geriatric medicine in addition to the initial five panel experts. The initial and second expert panels were provided the opportunity to add free text comments on the ESEU’s final version regarding their opinion on what ESEU could assist or bring them in their clinical daily practice in capturing patients’ personhood (24) and content analysis was used (25). The gathered free texts were read by two coders to capture the overall essence of each transcript. Initial coding was made by each coder, identifying priori codes with subsequent comparisons of coding. Later, intercoder agreement was obtained to reach consensus after solving any discrepancies.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®) software 23.0 for Windows®. Descriptive statistics were used to describe sociodemographic characteristics of the participants and responses to the feedback questionnaires.

Results

Translation

The Portuguese version of TIME Questionnaire was coined Questionário ESEU (Este Sou EU) and the Portuguese version of PDQ as Pergunta da Dignidade (PD). The full questionnaire is presented in Table 3.

Full table

Data collection

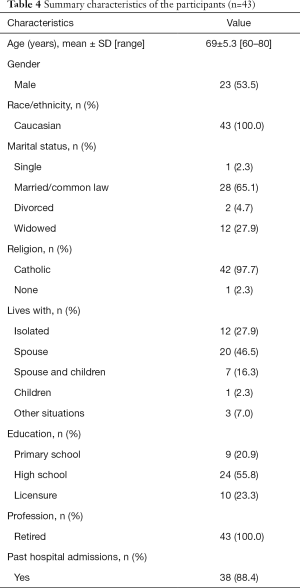

We used convenience sampling. There were 138 eligible people invited to take part in the study. Sixty-nine agreed to do so and the remaining 69 declined participation giving no reason for their decision. Twenty-six participants were excluded (one lacked Portuguese language proficiency, 5 declined after reading the questionnaire, 10 declined for personal reasons, 10 declined with no reasons given) leaving a final sample of 43 participants (response rate of 62%). No participants abandoned the study after reading TIME’s questionnaire. Fifty-three percent of our sample were male. The average age was 69 years old (range, 60–80 years old). All participants were Caucasian and the majority were married (65%) and Catholic (98%) (Table 4).

Full table

Participants favorably endorsed ESEU’s summary: 84% of the study participants found the summary accurate, 65% indicated it was complete and 88% said it was precise. Seventy-two percent wished to receive a copy of the summary, 86% would recommend ESEU to others and 88% would want a copy of the summary placed into their medical chart, if they were to be hospitalized.

Participants indicated that the ESEU initial explanation/instruction was clear and had sufficient information (5.9, SD =1.31; 5.7, SD =1.54, respectively). Participants found no major difficulties on ESEU item ambiguity (4.1, SD =2.23), overall and specific questions’ understanding (4.0, SD =2.22; 3.2, SD =2.13, respectively).

The interviewed elderly strongly felt that the ESEU's summary captured their essence as a person beyond whatever health problems they might be experiencing (6.8, SD =0.48), heightening their sense of dignity (6.1, SD =1.48), and considered it important that HCP have access to ESEU’s summary (6.6, SD =0.73) and that this information could affect the way HCP see and care for them (6.4, SD =0.86), allowing professionals to know about what really matters to them (6.8, SD =0.47), their life’s values (6.8, SD =0.48), concerns and preferences (6.7, SD =0.59) and main areas of distress (6.5, SD =0.97) (Table 2). While participants felt that ESEU responses were critical for HCPs to know, they wished to place their summaries in their bedroom/bedside/ward (5.9, SD =1.92) and wanted to receive copies (5.7, SD =2.38); they did not show a strong desire to deliver it to family or friends (3.6, SD =2.67).

Final expert panel consult

According to the experts’ evaluations, the translated ESEU Questionnaire was clear, precise, comprehensible and captured important dimensions of personhood. After performing content analysis on experts free texts several categories emerged reinforcing the ESEU’s role in clinical practice: “eliciting patients’ individual narrative”; “life’s story”; “awareness of vulnerability”; “shifting care needs”, “wholeness”; “respect”; “caring”; “dignity opportunity”; “patients and HCP’ satisfaction”; “care of the whole person”; “change of care perspective”; “patients’ future objectives”. The experts also added that this questionnaire could add additional value to their therapeutic relationship with patients, allowing a new perspective on how they would perceive patients as persons, in spite of the encumbrances of their illness.

Discussion

This study reports the development of the European Portuguese version of the TIME Questionnaire, which includes the PDQ. By way of engaging the original expert panel after data collection, including three additional geriatric experts to the initial panel, ESEU’s clinical applications and importance were further clarified. Indeed, there was consensus about how the use of ESEU could contribute to patients feeling taken care of and at the same time informing doctors regarding dimensions of personhood that are not a regular part of the clinical encounters. The qualitative feedback, provided in free text from members of the expert panel, highly endorsed the ESEU. This confirms the utility and relevance of the questionnaire in clinical practice. A panel of experts—all potential users of the ESEU—unanimously recognized that it could enhance knowledge and affirm personhood in consultations.

This paper describes the steps in translating and adapting the TIME questionnaire and the PDQ into European Portuguese, coined as Questionário ESEU and PD, respectively. Judgments by bilingual experts were essential to establish face validity and content accuracy, ensuring the questionnaire elicits dimensions of personhood as it was intended to. The ESEU is worded in simple language, to allow its use in the largest possible population. As part of the study, 43 respondents were surveyed, affirming that the items were comprehensible and did not cause discomfort. Participants also agreed that the number of included items and time to respond were adequate. The perceptions about the summary elicited by ESEU were largely favorable, with participants agreeing on the comprehensiveness of the summary and demonstrating a clear willingness to share these with their health caregivers—a participant said that “although not being sick at the moment of the study, she would place her summary near her medical exams to take with her whenever she had to go and have an appointment.” This affirms that the notion of personhood is a substantial part of feeling cared for as a patient. The fact that the items are open ended and worded as questions likely contributes to its acceptability by respondents.

The main limitation in our study is that by using convenience sampling all participants came from one site only (Gondomar, Portugal), which means they were all non-institutionalized active elderly. This could affect the generalizability of our results and indeed, when comparing them to the original measure, unlike the majority of Canadian nursing home residents, most of our participants did not see the need to deliver their summary’s copies to family or friends. This may have to do with the fact that participants in our sample were still engaged and fully active in their lives. This might suggest that the need to affirm personhood is likely more pressing amongst those experiencing heightened vulnerability and more profound relational needs, resulting from a change in health status. Furthermore, as participants had a formal education, it should also be considered that they may find the concepts and questions easier to understand; thus, further studies, considering less educated or engaged individuals, should be conducted. Additionally, it is also probable that content validity of dignity and personhood, as well as acceptability in itself, might be different in frail or sick older people. Finally, we would alert that the measures be used in a language and culture in which individuals are completely at ease. Not only a basic knowledge of the language is needed, but also the cultural context of care, which is particularly important when dealing with personal questions and reflections.

Nevertheless, our results are well aligned with the literature in the area of narrative medicine, which underscores the importance of narrative, not only as part of medical care, but as critical information that must be acknowledged within healthcare encounters.

Decision-making in medicine brings together the intellectual, emotional and imaginative dimensions of the human being, demanding that the uniqueness of the individuals involved is respected. The plot in which the patient is situated demands that caregivers respond as readers of that narrative (26,27). The ESEU may be one way of providing healthcare providers insight into the patient narrative, thereby enhancing their response to patients’ emotional and spiritual needs.

In the future, it would be important to (I) test the impact of the Questionário ESEU on the HCP, determining its acceptance and whether they feel the information influences their care of patients, and (II) determine if the measures are feasible for use in routine care. It will be further interesting to see if the ESEU influences Portuguese HCP attitudes, care, respect, empathy/compassion, and sense of connectedness with patients; and heightens personal satisfaction in providing care. Although Portugal’s nursing homes are not exactly equivalent to the Canadian ones, it would be important to test the ESEU in Portuguese institutionalized residents and compare the results. Nevertheless, this study provides support for the idea that the ESEU is equivalence to TIME, and has the potential to enhance dignity in elderly care settings.

Conclusions

The Portuguese ESEU Questionnaire is clear, precise, comprehensible and well-aligned in terms of measuring personhood. It may enhance patient/HCP relationships, allowing a new perspective on how professionals perceive and respond to personhood within the clinical setting.

Acknowledgements

A special word of gratitude to Dr. José António da Silva Macedo and Alcídio Jesus from the União das Freguesias de Gondomar (S. Cosme), Valbom e Jovim for his constant support during the study. Sincere thanks to the clinicians who participated in the expert panel. To each and every participant who agreed to enter our study.

Funding: B Antunes is funded by Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) PhD Fellow Grant number PD/BD/113664/2015 Doctoral Program in Clinical and Health Services Research (PDICSS) funded by FCT Grant number (PD/0003/2013); F Fareleira is funded by Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) PhD Fellow Grant number PD/BD/132860/2017 Doctoral Program in Clinical and Health Services Research (PDICSS); N Correia Santos: this work has been developed under the scope of the project NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000013, supported by the Northern Portugal Regional Operational Programme (NORTE 2020), under the Portugal 2020 Partnership Agreement, through the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), and was co-financed by the Portuguese North Regional Operational Program (ON.2—O Novo Norte), under the National Strategic Reference Framework (QREN), through FEDER. N Correia Santos is supported by a Research Assistantship by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) through the “FCT Investigator Programme (200 ∞ Ciência)”.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study received ethical approval from the Unidade de Coordenação Geral, Desenvolvimento Local e Fundos Estruturais da União das Freguesias de Gondomar (S. Cosme), Valbom e Jovim (N/Ref 0115/2017) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med 1982;306:639-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA 2001;286:1897-902. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pichert J, Hickson G, Moore I. Using patient complaints to promote patient safety. In: Henriksen KBJ, Keyes MA, Grady ML, eds. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008.

- Vincent C, Young M, Phillips A. Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action. Lancet 1994;343:1609-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maguire P, Faulkner A, Booth K, et al. Helping cancer patients disclose their concerns. Eur J Cancer 1996;32A:78-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sage WM. Medical liability and patient safety. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22:26-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. BMJ 2007;335:184-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teutsch C. Patient-doctor communication. Med Clin North Am 2003;87:1115-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hickson GB, Pichert JW, Webb LE, et al. A complementary approach to promoting professionalism: identifying, measuring, and addressing unprofessional behaviors. Acad Med 2007;82:1040-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shore M, Dienstag J, Mayer R, et al. A complementary approach to promoting professionalism: identifying, measuring, and addressing unprofessional behaviors. Acad Med 2007;82:845-52. [PubMed]

- Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Dauphinee D, et al. Physician scores on a national clinical skills examination as predictors of complaints to medical regulatory authorities. JAMA 2007;298:993-1001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kearney MK, Weininger RB, Vachon ML, et al. Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: “Being connected. a key to my survival JAMA 2009;301:1155-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1377-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meier DE, Back AL, Morrison RS. The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA 2001;286:3007-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weng HC. Does the physician’s emotional intelligence matter? Impacts of the physician’s emotional intelligence on the trust, patient-physician relationship, and satisfaction. Health Care Manage Rev 2008;33:280-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Julião M. Human Dignitas, Dignity in Care - A Precious Need. Int J Emerg Ment Health 2015;17:598-9. [Crossref]

- Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, et al. Eliciting Personhood Within Clinical Practice: Effects on Patients, Families, and Health Care Providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:974-80.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pan JL, Chochinov H, Thompson G, et al. The TIME Questionnaire: A tool for eliciting personhood and enhancing dignity in nursing homes. Geriatr Nurs 2016;37:273-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dignity. Oxford Dictionaries. Available online: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/dignity

- Chochinov HM, Hack T, McClement S, et al. Dignity in the Terminally Ill: A Developing Empirical Model. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:433-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM. Dignity and the Eye of the Beholder. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1336-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Personhood. Oxford Dictionaries. Available online: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/personhood

- McKenzie JF, Wood ML, Kotecki JE, et al. Establishing content validity: Using qualitative and quantitative steps. Am J Health Behav 1999;23:311-8. [Crossref]

- Glaser BG, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1967.

- Klitzman R. When Doctors become Patients. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Leape LL, Shore MF, Dienstag JL, et al. Perspective: a culture of respect, part 2: creating a culture of respect. Acad Med 2012;87:853-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]