Ethical challenges of outcome measurement in palliative care clinical practice: a systematic review of systematic reviews

Introduction

Measurement is a fundamental component of evidence-based medicine and provides the information needed for clinicians to make decisions in patient care and management (1). It is therefore not surprising that several outcome measures have been systematically implemented to be used in palliative care, as they play an increasing role in improving the quality, effectiveness, efficiency and availability of this type of care (1-3).

A person (or patient)-centred approach is being promoted in this field, as the person (or patient)’s perspective should inform clinical practice and inherent decision-making processes (1,2,4-6). Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), which can be also called patient-centred outcome measures (PCOMs), are an important and standardised way of promoting patient-professional communication, by asking patients to complete validated questionnaires that measure their perceptions of their own status and wellbeing (1,2,4-6).

Person (or patient)-centred outcome measures are considered to be the gold standard for outcome measurement of subjective experiences (1,4,7). In palliative care, this is of foremost relevance as it may (I) facilitate the identification and screening of physical, psychological, spiritual and social needs, (II) provide information about the experience of the disease trajectory and process, (III) enable patient-family-clinician communication and promote, simultaneously, a person-centred care approach, a shared decision-making process and advance care planning, and (IV) give relevant information to monitor the quality of care provided and its costs (1). These mechanisms are aligned with several ethical principles, namely, the ethical principles of integrity [an ethical principle that focuses on enhancing the holistic perspective of care, the coherence of life, which is remembered from experiences and can be told in a narrative (8,9)], dignity [ethical principle that highlights the intrinsic quality of personhood (8-10)], autonomy [in the sense of self-determination and meeting the person-patient’s wishes and preferences for care (8,10-13)], beneficence and non-maleficence [defined as the dual obligation healthcare professionals have to seek to maximize the benefit and to prevent as much as possible any potential harm (8,10-13)], and even justice [as equitable access to care and fairness in the allocation of health resources (8,10-14)].

Nevertheless, routine use of person (patient)-centred outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice is not without ethical challenges. While several international studies report on the validation, implementation, and use of this type of measures in clinical practice, referring to its barriers and facilitators (1,4,15-17), ethical challenges/issues are not commonly or specifically addressed.

The objectives of this study are therefore (I) to identify the ethical challenges/issues of outcome measurement in palliative care and (II) to understand how these ethical challenges/issues are addressed in palliative care clinical practice.

Methods

This study consists of a systematic review of systematic reviews. This is a type of review that brings together a summary of reviews in one place (18).

Systematic review of systematic reviews: methodological considerations

A systematic review of systematic reviews is a logical and appropriate approach that allows the findings of separate reviews to be compared and contrasted, providing relevant information on the topic of interest (18). It is suitable for describing the quality, discerning the heterogeneity, and identifying lacunas in the current evidence, since it synthetizes evidence from relevant previous systematic reviews (19).

Since several systematic reviews have already been published about outcome measurement in palliative and end of life care clinical practice, we found it appropriate to analyse and synthetize the evidence from these existing reviews with respect to our objectives. The methodological steps recommended by Whitlock et al. (20) were followed and adapted in our systematic review of systematic reviews (Figure 1).

Sources and searching

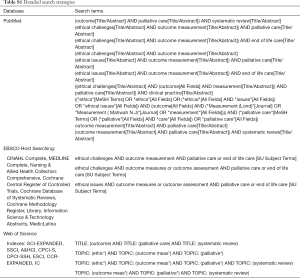

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCOhost searching CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE Complete, Nursing & Allied Health Collection: Comprehensive, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Methodology Register, Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, MedicLatina, from inception to January 2018. This search was complemented with the manual search of journals from the field of palliative care. Reference lists of the retrieved articles were screened for additional studies.

Systematic reviews were identified, screened and assessed for inclusion based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in Table 1. The following search terms were used: “outcome” AND “palliative care” AND “systematic review”. The general search strategy is presented in Table 2 and further details are provided in Table S1.

Full table

Full table

Full table

Review selection

Systematic reviews identified through the search were examined for inclusion in a three-step process. First, we performed an initial screening of titles and removed any duplicates and review protocols. Second, the abstracts of the remaining studies were assessed, with eligible systematic reviews being further subjected to full-text screening. Third, we screened full-text systematic reviews against the inclusion criteria to identify relevant studies to be included in our systematic review of systematic reviews.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

The search strategy was designed by S Martins Pereira and P Hernández-Marrero. Studies were independently identified and assessed by S Martins Pereira and P Hernández-Marrero. Doubts about the inclusion of papers were discussed and decided by consensus between the two researchers. Data from the studies were extracted into a table by S Martins Pereira. P Hernández-Marrero complemented data extraction independently. All systematic reviews and data were thoroughly analysed by S Martins Pereira and P Hernández-Marrero independently, based on the objectives of the study. If there was any uncertainty about inclusion, eligibility or analysis of data, these were further discussed by the two researchers until reaching consensus. Systematic reviews and data were thematically analysed by S Martins Pereira and P Hernández-Marrero. Data were extracted from the identified articles and tabulated according to PICO’s methodology: P—Participants/Population/People/Patient/Problem, I—Intervention(s), C—Comparison/Control, O—Outcome (21-25). A thematic analysis was performed to extract the main themes aligned with our research objectives.

Results

Characteristics of the systematic reviews

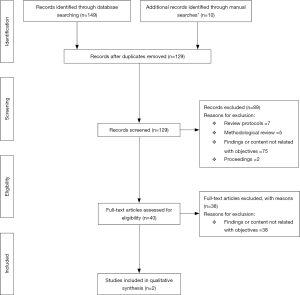

Out of 159 articles screened, only two articles were included for analysis. Figure 2 illustrates our PRISMA (26) flowchart.

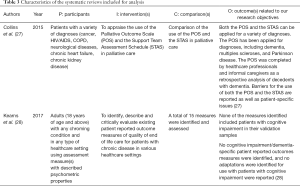

Out of the two systematic reviews included for analysis, one focused on the use of the Palliative Outcome Scale and of the Support Team Assessment Schedule in palliative care (27) and the other focused on existing PROMs of quality end of life care (28). Table 3 summarizes the main characteristics of these two systematic reviews using the PICO methodology (21-25) as a framework.

Full table

Quality assessment of the systematic reviews included for analysis

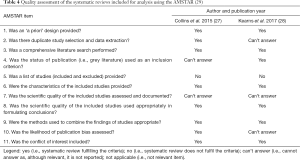

After review selection, the methodological quality of the systematic reviews was assessed using the AMSTAR tool (29-31). This is an empirically developed instrument for documenting the quality of systematic reviews and it was found to have good agreement, reliability and construct validity (29-31). The AMSTAR tool refines and enhances previous published instruments used to assess the quality of systematic reviews (29,32,33). It is considered to be a successful tool, and it is widely used in the quality assessment of systematic reviews in healthcare and palliative care research (34-38). Based on the use of this tool, the two systematic reviews included in our systematic review can be considered of good quality as they met, respectively, 8 and 7 out of the 11 AMSTAR items/criteria (Table 4).

Full table

Ethical challenges/issues of outcome measurement in palliative care

Ethical challenges/issues are poorly addressed in the existing systematic reviews about outcome measurement in palliative care clinical practice. In fact, only two systematic reviews addressed ethical challenges/issues as part of their findings. The main ethical challenge/issue mentioned in these two systematic reviews was cognitive impairment, particularly in patients with dementia. One study (Collins et al.) mentioned that the Palliative Outcome Scale had been applied for different types of diagnoses, including dementia. In the case of patients with dementia, completion had been made by healthcare professionals and informal caregivers (27). The other study (Kearns et al.) highlighted that none of the measures identified included patients with cognitive impairment in their validation samples. According to the authors of this second study, neither cognitive impairment/dementia-specific patient reported outcome measures were identified nor adaptations of these type of measures for use with patients with cognitive impairment (28).

Addressing ethical challenges/issues of outcome measurement in palliative care

The main way of addressing the lack of capacity in completing an outcome measure due to cognitive impairment was using proxy measures. This was particularly highlighted by Collins et al. (27) who referred to the use of specific outcome measures, such as the Palliative Outcome Scale, that can be completed by a proxy (family member or healthcare professional).

Table 5 illustrates these findings with quotations from the included systematic reviews.

Full table

Discussion

Summary of main findings

Ethical challenges/issues are poorly addressed in the existing systematic reviews about outcome measurement in palliative care clinical practice. Only two systematic reviews addressed ethical challenges/issues as part of their findings. The main ethical challenge/issue mentioned in these two systematic reviews was cognitive impairment, particularly in patients with dementia. This ethical challenge/issue was addressed via proxy measurement.

The ethical challenge/issue of outcome measurement in patients with cognitive impairment, particularly dementia

Our findings show that the main ethical challenge/issue of outcome measurement in palliative care clinical practice is cognitive impairment, particularly in patients with dementia. Considering the trend of the ageing population in developed countries worldwide, this is of foremost relevance and constitutes a major concern as most of the people living and dying in old ages will face some type of dementia (39-43).

From an ethical perspective, by either excluding patients with dementia or cognitive impairment from their study samples or by performing a proxy-assessment of needs and outcomes, it seems that some vulnerable patients are at risk of developing further vulnerabilities. According to Kipnis (44,45), there are seven categories of vulnerabilities: incapacitational or cognitive (when the person lacks the capacity to deliberate and make a decision), juridical (when the person is declared to be legally incompetent to make decisions), situational (when the person is in a situation in which medical exigency prevents the time, education and deliberation needed to make a decision), medical (when the person has a medical, serious health-related condition that may increase vulnerability), allocational (when the person lacks in subjectively important social goods), social (when the person belongs to a group whose rights and interests are socially disvalued), and deferential (when the person may be at risk of having a deferential behaviour and agrees on something regardless of his/her willingness to actually do so). Considering our findings, cognitive impairment (which may be linked to cognitive vulnerability) may be increased by other categories of vulnerability (medical, allocational and social, for instance) if patients with dementia are systematically being left out of relevant research that may assess and improve the outcomes of the care they are receiving. According to Harrison et al. (46), the field of dementia and cognitive impairment has fewer evidence-based interventions when compared to many other common diseases. Nevertheless, it is known that providing high-quality medical treatment or healthcare requires high-quality research and evidence. In other words, assessing medical interventions or care provision requires some measure of treatment or care effect (46). This situation becomes even more complex, as evidence shows that patients with dementia, particularly older patients, are less likely to be referred to palliative care services (47-50). Furthermore, it is known that most of the evidence sustaining palliative care provision is built on research in other diseases/medical conditions (51-54). From an ethical perspective, the ethical principle of justice in the access to both research and palliative care services seems to be compromised.

The main challenges posed to outcome measurement in patients with dementia and/cognitive impairment occur at the end of life (2). At this stage, increasing cognitive impairment and physical dependence may indicate that palliative care is the appropriate approach. Decision-making capacity remains as an ethical issue to consider, which needs to be balanced in light of the patient’s vulnerability and of other ethical principles and values (e.g., beneficence, non-maleficence, integrity, dignity, respect, empathy, trust) that should be taken into consideration in clinical practice and research.

Questions can also be raised about whether or not the measurement of psychological, social and spiritual concerns, problems, needs and care outcomes at this level is reliable at all in advanced dementia patients (2). As for other interventions requiring consent and decision-making capacity, proxy assessment can indeed be an alternative source of information that can be particularly useful at the end of life (2,3). The validity of such ratings has however been discussed, with suggestions that proxies tend to overestimate the patient’s experiences and that healthcare professionals tend to underestimate them (55,56). Evidence shows that the continuing use of proxies rather than direct self-report for quality of life measures can be problematic, particularly considering the growing reports that show discrepant ratings between self-reports and proxy reports (55-61).

Implications of this systematic review of systematic reviews

This systematic review of systematic reviews shows that the ethical challenges/issues are poorly addressed in the existing systematic reviews about outcome measurement in palliative care clinical practice. A few possible explanations can be hypothesized on why this occurs. On the one hand, there might be the case that once the research studies on outcome measures are approved by ethical boards, clinicians and researchers might consider that all ethics procedures are safeguarded when using those measures in clinical practice. On the other hand, as scientific journals commonly only ask whether or not the study complies with required ethics procedures, authors may not feel obliged to provide further details on this matter. A third possible reason could be that clinicians and researchers might consider ethics procedures in clinical dementia research as a barrier to conduct research studies that include patients with dementia as participants. In our opinion, further research is needed to allow a better understanding of the reasons behind this finding.

Nevertheless, and taking into account the overall findings of our systematic review of systematic reviews, a set of recommendations can be driven. First, more research is needed specifically focusing on the ethical challenges/issues that outcome measurement raises in palliative and end of life care clinical practice. Second, there is also the need to foster and improve the use of tailored outcome measures, designed to meet the specific needs and conditions of patients with cognitive impairment and/or dementia. As an example, decision aids (e.g., videos, visual images or other non-conventional informed consent forms) for people with dementia and/or impaired decision-making capacity have been described to improve informed consent and decision-making capacity about considering taking part in clinical trials (62-66). While findings are not consensual, they show the increasing use of these aids. Similar studies could be conducted to tailor the use of person (or patient)-centred approaches for outcome measurement in people with cognitive impairment and/or dementia. While some initiatives have been done to validate and implement the use of PROMs in persons with dementia (67), very little is known on the use of aid tools when measuring outcomes in this group of patients. Third, it is known that patients with dementia often have multiple problems, frailties and vulnerabilities. Disease-oriented structures and models of research funding are not applicable for this type of patients, as they do not easily fit into existing disease-oriented research designs (68). Due to these vulnerabilities and to cognitive impairment that may compromise their decision-making capacity, persons with dementia are more at risk of being left out of some relevant research projects. More research and funding are needed for palliative care research, especially including older people and people with dementia or cognitive impairment, and not necessarily for disease-orientated projects. In fact, international and national funding policies are urged to provide more funding in order to support quality research focusing on the needs and problems of all people, regardless of their age or disease (68).

Strengths and limitations

This study tackles the paucity of research on the ethical issues/challenges that may occur in outcome measurement in palliative care clinical practice. This is of foremost relevance as high quality care and high quality research cannot be without high ethical standards. Moreover, sensitive search strategies with few limitations and in a range of literature databases were performed, and methodological frameworks (20) and reporting guidelines (26) were followed to ensure the trustworthiness and reliability of our findings. Nevertheless, this systematic review of systematic reviews is not without limitations. Since we could not find any primary evidence about ethical issues/challenges in outcome measurement in palliative care, but we believed that there were already many systematic reviews on outcome measurement in this field, we decided to perform a systematic review of systematic reviews. While this assumption was correct, none of these systematic reviews was specifically focused on ethical issues/challenges and we could only find two systematic reviews addressing ethical issues/challenges in their findings/discussion. Therefore, caution is needed in the interpretation of our findings. Finally, as recommended by Whitlock et al. (20), a more robust dialogue and methodological research are needed to better assist with the specification of methods and development of reporting standards when performing and conducting systematic reviews of systematic reviews.

Conclusions

Ethical challenges/issues are poorly addressed in the existing systematic reviews about outcome measurement in palliative care clinical practice. Only two systematic reviews addressed ethical challenges/issues as part of their findings. The main ethical challenge/issue mentioned in these two systematic reviews was cognitive impairment, particularly in patients with dementia. Further research is needed on this subject and to foster the use of outcome measurement among this vulnerable group of patients. Recommendations are driven to tackle the paucity of research on ethical challenges/issues in outcome measurement in palliative care clinical practice and on how to improve person-centred outcome measurement for people with dementia/cognitive impairment.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was written during the duration of Projects InPalIn “Integrating Palliative Care in Intensive Care” and Subproject ETHICS II of Project ENSURE “Enhancing the Informed Consent Process: Supported Decision-Making and Capacity Assessment in Clinical Dementia Research”. Therefore, SMP and PHM would like to thank Fundação Merck, Sharp & Dohme and Fundação Grünenthal for their financial support to Project InPalIn and ERA-NET NEURON II, ELSA 2015, European Comission, and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior, Portugal, for their financial support to the Subproject ETHICS II of Project ENSURE NEURON-II/0001/2015. The funders had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Antunes B, Harding R, Higginson IJ, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care: A systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliat Med 2014;28:158-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bausewein C, Daveson BA, Currow DC, et al. EAPC White Paper on outcome measurement in palliative care: Improving practice, attaining outcomes and delivering quality services - Recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Task Force on Outcome Measurement. Palliat Med 2016;30:6-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bausewein C, Daveson B, Benalia H, et al. Outcome Measurement in Palliative Care. The Essentials. London: PRISMA, 2009.

- Etkind SN, Daveson BA, Kwok W, et al. Capture, transfer, and feedback of patient-centered outcomes data in palliative care populations: does it make a difference? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:611-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dawson J, Doll H, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ 2010;340:c186. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, et al. What Is the Value of the Routine Use of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Toward Improvement of Patient Outcomes, Processes of Care, and Health Service Outcomes in Cancer Care? A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1480-501. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carr AJ, Higginson IJ. Measuring quality of life: are quality of life measures patient centred? BMJ 2001;322:1357. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martins Pereira S, Fradique E, Hernández-Marrero P. End-of-Life Decision Making in Palliative Care and Recommendations of the Council of Europe: Qualitative Secondary Analysis of Interviews and Observation Field Notes. J Palliat Med 2018;21:604-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kemp P, Rendtorff JD. The Barcelona Declaration. Synth Philos 2008;46:239-51.

- Beauchamp TL. Methods and principles in biomedical ethics. J Med Ethics 2003;29:269-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Council of Europe. Guide on the decision-making process regarding medical treatment in end-of-life situations. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2014.

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Beauchamp TL. History and theory in "applied ethics". Kennedy Inst Ethics J 2007;17:55-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norheim OF, Asada Y. The ideal of equal health revisited: definitions and measures of inequity in health should be better integrated with theories of distributive justice. Int J Equity Health 2009;8:40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Potts M, Cartmell KB, Nemeth L, et al. A Systematic Review of Palliative Care Intervention Outcomes and Outcome Measures in Low Resource Countries. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:1382-1397.e7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michels CT, Boulton M, Adams A, et al. Psychometric properties of carer-reported outcome measures in palliative care: A systematic review. Palliat Med 2016;30:23-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bausewein C, Le Grice C, Simon S, et al. The use of two common palliative outcome measures in clinical care and research: a systematic review of POS and STAS. Palliat Med 2011;25:304-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, et al. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Slev VN, Mistiaen P, Pasman HR, et al. Effects of eHealth for patients and informal caregivers confronted with cancer: A meta-review. Int J Med Inform 2016;87:54-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Chou R, et al. Using existing systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:776-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heneghan C, Badenoch D. Evidence-based Medicine Toolkit. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Care of Dying Adults in the Last days of Life. NICE Guideline Nº. 31. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015.

- Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, et al. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2007;7:16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:395-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Qual Health Res 2012;22:1435-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009;6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collins ES, Witt J, Bausewein C, et al. A Systematic Review of the Use of the Palliative Care Outcome Scale and the Support Team Assessment Schedule in Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:842-53.e19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kearns T, Cornally N, Molloy W. Patient reported outcome measures of quality of end-of-life care: A systematic review. Maturitas 2017;96:16-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shea BJ, Bouter LM, Peterson J, et al. External validation of a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR). PLoS One 2007;2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1013-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. Validation of an index of the quality of review articles. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:1271-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sacks HS, Berrier J, Reitman D, et al. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. N Engl J Med 1987;316:450-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Hartling L. Evaluation of AMSTAR to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews in overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017;17:48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pussegoda K, Turner L, Garritty C, et al. Systematic review adherence to methodological or reporting quality. Syst Rev 2017;6:131. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rogante M, Giacomozzi C, Grigioni M, et al. Telemedicine in palliative care: a review of systematic reviews. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2016;52:434-42. [PubMed]

- Wu X, Chung VC, Hui EP, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies for palliative care of cancer: overview of systematic reviews. Sci Rep 2015;5:16776. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moens K, Higginson IJ, Harding R, et al. Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:660-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Albers G, Martins Pereira S, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, et al. A public health perspective to palliative care for older people: An introduction. In: Van den Block L, Albers G, Martins Pereira S, et al. editors. Palliative Care for Older People. A public health perspective. Oxford: OUP, 2015:3-15.

- World Health Organization. Interesting facts about ageing. Available online: (accessed April 2014: Ref. Type: Online Source.http://www.who.int/ageing/about/facts/en/

- World Health Organization. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment throughout the life course. EB134/28. 134th session; 2013.

- Alzheimer's Disease International. Dementia Statistics. Available online: (accessed February 2014). Ref. Type: Online Data.https://www.alz.co.uk/research/statistics

- Dunn LB, Misra S. Research ethics issues in geriatric psychiatry. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2009;32:395-411. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kipnis, K. Vulnerability in research subjects: A bioethical taxonomy. In: National Bioethics Advisory Commission [NBAC]. Ethical and Policy Issues in Research Involving Human Participants. Volume II: Commissioned Papers. Rockville: NBAC, 2001:G1-G13.

- Kipnis K. Seven vulnerabilities in the pediatric research subject. Theor Med Bioeth 2003;24:107-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harrison JK, Noel-Storr AH, Demeyere N, et al. Outcomes measures in a decade of dementia and mild cognitive impairment trials. Alzheimers Res Ther 2016;8:48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walshe C, Todd C, Caress A, et al. Patterns of access to community palliative care services: a literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37:884-912. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sampson EL. Palliative care for people with dementia. Br Med Bull 2010;96:159-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller SC, Lima JC, Intrator O, et al. Specialty Palliative Care Consultations for Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;54:9-16.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sampson EL, Candy B, Davis S, et al. Living and dying with advanced dementia: A prospective cohort study of symptoms, service use and care at the end of life. Palliat Med 2018;32:668-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iliffe S, Davies N, Vernooij-Dassen M, et al. Modelling the landscape of palliative care for people with dementia: a European mixed methods study. BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies N, Maio L, van Riet Paap J, et al. Quality palliative care for cancer and dementia in five European countries: some common challenges. Aging Ment Health 2014;18:400-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fox S, FitzGerald C, Harrison Dening K, et al. Better palliative care for people with a dementia: summary of interdisciplinary workshop highlighting current gaps and recommendations for future research. BMC Palliat Care 2017;17:9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2014;28:197-209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McPherson CJ, Addington-Hall J. Judging the quality of care at the end of life: can proxies provide reliable information? Soc Sci Med 2003;56:95-109. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laugsand EA, Sprangers MA, Bjordal K, et al. Health care providers underestimate symptom intensities of cancer patients: a multicenter European study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruera E. Poor correlation between physician and patient assessment of quality of life in palliative care. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2006;3:592-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- EU Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND Research). Dementia outcome measures: charting new territory. Report of a JPND Working Group on Longitudinal Cohorts; 2015. Available online: (accessed February 2018). Ref. Type: Online Data.http://www.neurodegenerationresearch.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/JPND-Report-Fountain.pdf

- Moyle W, Murfield JE, Griffiths SG, et al. Assessing quality of life of older people with dementia: a comparison of quantitative self-report and proxy accounts. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:2237-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thorgrimsen L, Selwood A, Spector A, et al. Whose quality of life is it anyway? The validity and reliability of the Quality of Life-Alzheimer's Disease (QoL-AD) scale. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2003;17:201-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zloklikovits S, Andritsch E, Frohlich B, et al. Assessing symptoms of terminally-ill patients by different raters: a prospective study. Palliat Support Care 2005;3:87-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Volandes AE, Mitchell SL, Gillick MR, et al. Using Video Images to Improve the Accuracy of Surrogate Decision-Making: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009;10:575-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillies K, Cotton SC, Brehaut JC, et al. Decision aids for people considering taking part in clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015. [PubMed]

- Coyne CA, Xu R, Raich P, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an easy-to-read informed consent statement for clinical trial participation: a study of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:836-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryan RE, Prictor MJ, McLaughlin KJ, et al. Audio-visual presentation of information for informed consent for participation in clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;1. [PubMed]

- Synnot A, Ryan R, Prictor M, et al. Audio-visual presentation of information for informed consent for participation in clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014. [PubMed]

- Ellis-Smith C, Evans CJ, Bone AE, et al. Measures to assess commonly experienced symptoms for people with dementia in long-term care settings: a systematic review. BMC Med 2016;14:38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martins Pereira S, Albers G, Pasman R, et al. A public health approach to improving palliative care for older people. In: Van den Block L, Albers G, Martins Pereira S, et al. editors. Palliative care for older people. A public health perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015:275-91.