The need for training in palliative care for physicians in other specialties: Brazilian nephrologists empowerment (or appropriation) on renal supportive care

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a growing, worldwide health problem, which impacts negatively on quality and quantity of life and affects economically patients and society (1).

Patients with advanced CKD have a high burden of stressful physical and psychological symptoms (2,3), similar to those occurring in other chronic diseases such as cancer (4,5). Studies have found a cluster of 6 to 20 symptoms per patient which negatively impacts quality of life (6) and are generally neglected by providers (7). In addition, both incidence and prevalence of patients on dialysis over 75 years of age has risen and it is the fastest growing palliative population in recent years (8,9). In 2016 there were 122,825 patients in dialysis in Brazil, with an annual increase in the last 5 years of 6.3%, and with 11.2% of patients aged ≥75 years (10). The annual mortality of patients on dialysis is around 18–25% in general population and about 38% for those 75 years old or older (8,10) but in fragile elderly patients it may exceed 50% (11). It is also worth noting that dialysis withdrawal precedes death in about a quarter of patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (8). Furthermore, the important role of comprehensive conservative care as an alternative option for patients with advanced CKD who refuse dialysis and in elderly individuals over 75 years of age is increasingly recognized (12-17).

Renal palliative care is an interdisciplinary model of person-centered medicine that seeks to optimize quality of life and preserve dignity during the trajectory of CKD (18). It is now recognized that renal palliative care needs should be identified early and increasingly managed into the routine CKD care (18). Therefore, it is important that the principles and strategies of palliative medicine—that is, patient symptom management, advance care planning, discussion and shared decision making on renal replacement therapy options, including dialysis and non-dialytic management of CKD, and delineation of patients’ preferences for end-of-life care—begin early and continue throughout the course of the disease (19,20). The aim of this study is to assess the knowledge, perception, attitude, experience and interest on renal palliative care among members of the Brazilian Society of Nephrology (BSN).

Methods

Study design and sample

This is a cross-sectional study using a web based survey in a secure platform, SuveyMonkey® (https:surveymonkey.com). Potential respondents were contacted via email if they were members of the BSN. The survey was anonymous to minimize the risk of bias of social desirability. This study follows the internationally established “Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES)” for conducting online questionnaires (21).

Research and content design

A questionnaire was developed based on a literature review (19,22-28) to include 35 items that evaluate knowledge, perception, attitude, practical experience and interest in palliative care education, as well as demographic data. After review by an expert (Barbara Antunes) some items were added and others changed. Subsequently the questionnaire was piloted with 7 nephrologists and refined to improve clarity. The final version of the questionnaire is available online (Supplemental file).

Ethics and data collection procedures

From May 23th to June 13th 2017 four e-mails were sent to each member of the BSN on day 0, 7, 14 and 21. E-mails were addressed personally to each member of the society and included a cover letter with the objectives of the study, the time needed to complete the questionnaire, a statement of confidentiality and the consent term. All e-mails had the same content except the latter which also included a notice that the research deadline would end within in a week. To be included in the study the respondent should be a member of the BSN. There were no exclusion criteria. No incentives were offered for survey completion and responses were collected and analyzed anonymously. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Americas Serviços Médicos located in Hospital Pro-Cardíaco, Rio de Janeiro, protocol number 2.058.501 and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

Participation rate was calculated dividing the number of replies to first question of the survey by the number of visitors to the first page. Completion rate was calculated by the number of participants answering the first question of the survey divided by the number of people submitting the last question (21). Descriptive statistics with categorical variables presented by frequency and percentage were used for demographics.

Comparisons between two categorical variables were performed using the chi-square test. Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis after quotes were extracted and tabulated. Two researchers reached consensus on final themes.

Results

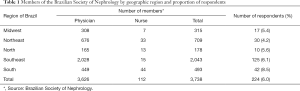

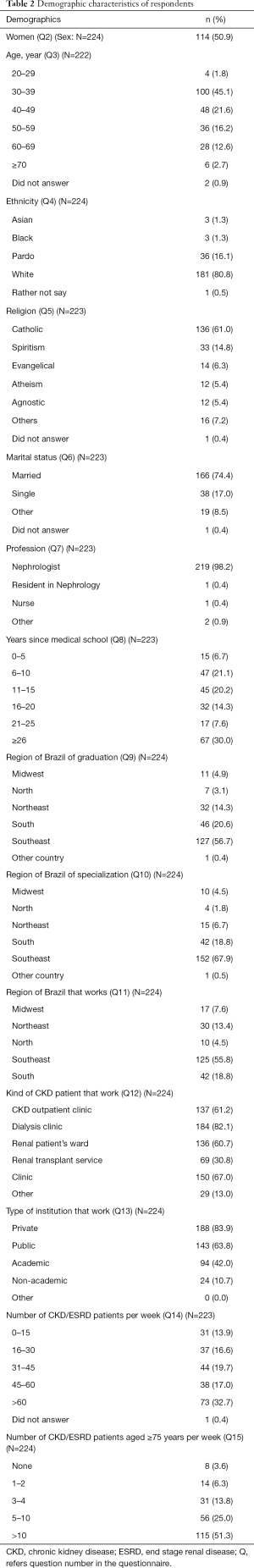

Emails were sent to the 3,738 members of the BSN. Number of participants were proportional to the number of members by region of the country (Table 1). One participant who completed the survey had answered “no” to the consent term and one other participant did not fill in the consent term. Since data were collected anonymously these answers were included in the analysis. In total, 224 (6%) members answered the online survey. Participation and completion rate was 100% (224/224 and 224/221, respectively). Table 2 shows demographic data of participants. Most respondents were under 50 years old (68.5%), White (80.8%), Catholic (61%) and married (74.4%). In relation to professional characteristics 98.2% of respondents were nephrologists, most of them were graduated (57%) specialized (67.9%) and are currently working in the Southeast of Brazil (56%). Furthermore, 52% were in practice for more than 15 years, most working in dialysis clinics (82.1%), in a private service (84%), see more than 30 CKD patients per week (69%) and 51% see more than 10 CKD patients who are 75 years old or older, per week (Table 2).

Full table

Full table

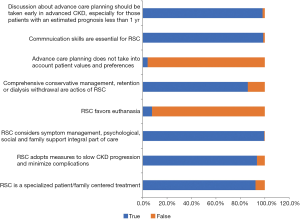

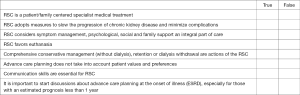

Renal supportive care knowledge

Most respondents have demonstrated assertiveness in relation to renal supportive care conceptualization, principles and actions explored in the question number sixteen (Figure 1). Some items of the questionnaire such as “renal supportive care favors euthanasia” and “comprehensive conservative management, withholding or withdrawing of dialysis are considered principles or actions of renal supportive care” were incorrectly marked as ‘true’ by 8% and ‘false’ by 14% of respondents, respectively.

Renal supportive care attitude

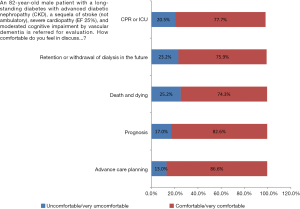

In relation to the scenario given (Figure 2) a quarter of respondents felt uncomfortable or very uncomfortable to talk about death and dying and withholding or withdrawing of dialysis. Additionally 46% of the respondents would probably continue dialysis if a competent patient asked him/her to discontinue dialysis treatment and 63% would probably continue dialysis if a patient became permanently and severely demented and had no advance directive. Eighty seven percent of respondents would probably not initiate dialysis in a permanently unconscious patient (e.g., permanent vegetative state or multiple stroke) and 92% probably would not resuscitate a patient with a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order if he/she were asked to. Professionals with 15 years of experience or more, were more prone to stop dialysis (P=0.01) in patients who became permanently and severely demented and had no advance directive. However, respondents working only in private practice would probably continue dialysis more than those who worked on a public healthcare system or both (P=0.02).

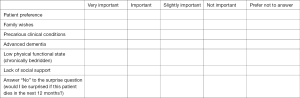

Renal supportive care perception

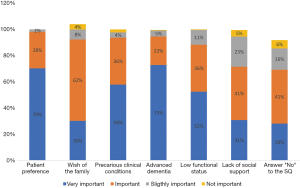

Among factors deemed important on a decision to not initiate dialysis but provide comprehensive conservative management, respondents top ranked patient preferences (98.2%), advanced dementia (95%), poor clinical conditions (93.7%) and family preferences (92.3%) (Figure 3).

Renal supportive care experience

Thirty five percent of respondents answered that in their place of work there was a palliative care service, 14% had worked in a palliative care service and 37% have had some training in this area, mainly in the place of work. Twenty four percent answered that they had already done a dedicated course in palliative care. Most respondents stated that they routinely screened for pain and other symptoms (79%) and health related quality of life (62%) in their CKD patients. Fifty percent answered they are frequently involved in discussions about end-of-life care with their patients. Furthermore, 27% answered to discuss DNR orders with their patients frequently. Nephrologists with more experience in palliative care were more prone to discuss about DNR orders (P=0.01) and death (P=0.04) with their patients than those without experience in palliative care.

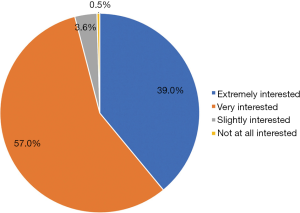

Interest in increasing knowledge about the subject and qualitative results

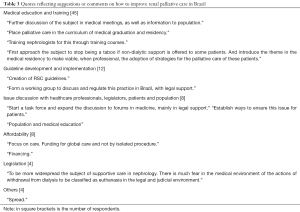

Most respondents (96%) were very interested in improving knowledge about renal supportive care (Figure 4). Respondents were asked to express, in a free comments box, if he/she had any suggestions or comments on how to improve renal supportive care in Brazil. Eighty four (36%) respondents expressed an opinion. There were different views regarding this theme, we analyzes the free comments statements and aggregated the data to final themes and subtopics. Among those who provided free comments, most (56%) suggested medical education and training to improve renal supportive care in Brazil (Table 3).

Full table

Discussion

In this national survey, less than half of respondents would honor an order of a competent patient to stop dialysis treatment. Surveys with nephrologists from US have shown that more than 90% of them would respect the request of a competent patient to stop dialysis since 1990 (29). Furthermore, in this survey more than a half of respondents would continue dialysis in a patient who became permanently and severely demented. Conversely, most of respondents would not initiate dialysis treatment in a patient that became permanently and severely demented. Additionally, most of them would not perform CPR in a patient with a DNR order. There are considerable geographical variability attitudes toward life-support limitation at the end-of-life. Besides advanced age, severity of illness and comorbidities, decision to withhold/withdraw life-sustaining treatment is heavily influenced by factors as societal values, religious and cultural beliefs, legal concerns and the subjective evaluation of benefits and burdens of the treatment (30). This practice is more prevalent in countries with a higher gross national income (30), mainly in Europe, North America and Oceania (31). Our data is aligned with some studies that have found that Brazilian physicians are more prone to withhold than withdrawn life-sustaining treatment (32,33). In one Brazilian survey with intensivists, 44% (98% of them believe that a less aggressive treatment would be preferable) of physicians would not do what they believed was best for their patient owing legal concerns and societal opinion (34). Notwithstanding the Federal Board of Medicine (CFM) in recent years had published resolutions about palliative care and advance healthcare directive, and the Code of Medical Ethics affirms patient’s autonomy, a Federal law on this topic is still missing in Brazil (35). Another point to consider when we analyze the low adherence of nephrologists to withdrawal of dialysis is that most of respondents in this study is Catholic. Brazil is a nation in which Roman Catholicism predominates and for the Catholic faith as long as there is a living body, even if mental capacities are reduced or absent, there is still a person present (36). A human being is considered to be a person from conception to the death of the whole (33). Studies have shown that non-Catholic affiliated physicians are more prone to recommend withdraw life-sustaining treatments (37,38). Taking all together, many factors contribute to nephrologists’ discomfort with confronting the limits of medical intervention (39,40).

In this study, respondents with ≥15 years of graduation were significantly more prone to stop dialysis in patients with advanced dementia and those who work in private practice were more willing to continue dialysis treatment. Seemingly findings have been observed in Europeans studies as well, where nephrologists of not-for-profit centers or public centers are more prone to select comprehensive conservative care or forgo dialysis than their peers of private services (26,41). Dialysis in Brazil is a citizen right and the model of assistance is disease-centered, as in USA and other countries, which results in disincentives for renal palliative care integration into routine care (42). Despite of withhold or withdrawal of an inappropriate or non-beneficial treatment is ethically and legally accepted as morally indistinguishable (43) for Brazilian nephrologists, they seem much more comfortable with not initiating than withdrawing a non-beneficial treatment. As in other studies (41), in this survey, patient preference is the foremost factor in a decision to not initiate dialysis followed by advanced dementia and poor clinical conditions. In contrast with studies from other cultures where patient autonomy is emphasized in the decision-making process (44) and only half of providers consider the wishes of the family as important (41), for more than 90% of Brazilian nephrologists, family wishes are considered relevant. This is in accordance with some studies which have found that Latinos prefer a family-centered decision-making model to discuss patient end-of-life care preferences (38,45,46).

In this survey most respondents demonstrated basic knowledge about some principles and actions of renal palliative care. However, there are still misconceptions that euthanasia is deemed a principle of renal palliative care for 8% of respondents. Additionally, comprehensive conservative care and withholding or withdrawing of dialysis were not deemed strategies of renal palliative care for 14% of respondents. Some authors have shown nephrologists erroneous beliefs regarding palliative care several years ago (29). Nevertheless, this scenario has been changed significantly lately overseas, probably related to the development of clinical practice guidelines (27), education (29,34,47), legislation (48) and high quality research in this area (49-51). We believe that most of this knowledge is still incipient for Brazilian nephrologists.

Surprisingly, more than one third or respondents worked in a place with a palliative care service or had some training in this area and a quarter had already done a dedicated course in palliative care. Furthermore, most respondents stated they made it a routine to screen for pain and other symptoms (79%) and health related quality of life (62%) in their CKD patients. Since most respondents (75%) came from more developed regions of the country as Southeast and South with much more provision of palliative care services (52), it’s possibly this influenced our findings. Despite half of respondents answered they frequently are involved in discussions about end-of-life care with their patients, only one quarter answered to discuss DNR order with their patients frequently. Nephrologists with more experience in palliative care were significantly more prone to discuss about DNR orders and death with their patients.

Finally, most participants are very interested in improving knowledge in palliative care.

This study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, it relies on nephrologists’ self-report behavior that may not accurately represent true behavior. Second, despite the use of best practice to online survey, the small number of respondents raises the possibility of non-response bias (53) which may limit generalizability. Nevertheless, other authors have obtained lower response rates than our survey (28). Most of respondents in this study were nephrologists and the rate of respondents by geographic region was similar and proportional to the number of members which ensures representativeness. Third, respondents who are more aware of palliative care feel more comfortable with its principles and actions and may have preferentially responded to the survey. Finally, the social desirability bias that has been shown to affect self-reported physician adherence to practice guidelines (54) may incline respondents to overestimate their comfort with highly sensitive topics of palliative care as prognosis, advance care planning, comprehensive conservative care, retention/withdrawal of dialysis, CPR and end-of-life care. To minimize this effect, it was emphasized the anonymous feature of data collection.

Conclusions

Brazilian nephrologists don’t often consider patient’s autonomy, are more prone to retention than withdrawing dialysis and deem wishes of the family as important as patient preferences in the shared decision-making process. Experienced nephrologists were significantly more prone to stop dialysis while those who work in private practice were more willing to continue dialysis treatment. Nephrologists trained in palliative care are significantly more involved in discussion about DNR order and end-of-life care with their patients. They have demonstrated basic knowledge and interest about renal palliative care, but a significant number of them still have erroneous beliefs regarding palliative care principles and actions. Further multifaceted interventions are needed to improve renal palliative care in Brazil.

Supplementary

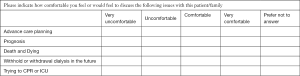

Questionnaire—Renal Supportive Care

Consent to participate

I am voluntarily taking the decision to participate in this research “Knowledge, perception, attitude and experience about Renal Support Care in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease” which aims to understand the knowledge, perception, attitude and experience about Renal Support Care in patients with Advanced DRC.By ticking “yes” or “no” in one of the answers boxes of the first question I indicate that I have read and understood that:

- My participation involves the completeness of an online survey that will take about 10 minutes;

- My response will be confidential and anonymous;

- The results of the research will be presented or published in scientific journals;

- If I have any question regarding the content of the research, I can contact Dr. Alze Tavares - Phone: 55-1198383-0115 E-mail: alzetavares@gmail.com;

- Ethics in Research Committee (CEP) is an interdisciplinary and independent collegiate body with a “public munus”, which must exist in institutions that conduct research involving human beings in Brazil, created to defend the interests of the participants in their integrity and dignity and to contribute to the development of research within ethical standards (Norms and Guidelines for Research Involving Human Beings - Resolution CNS 466/12).

If you have any questions regarding the ethical aspects of this research, you can contact the Ethics Committee for Human Research at Pro-Cardiac Hospital, Rua Voluntários da Pátria, 435/8o. Floor, Botafogo/RJ 22270-005, telephone (21) 3289-3802, from Monday to Friday from 09:00 to 16:00.

- I agree to participate in this survey

- Yes

- No

- Please enter your gender

- Female

- Male

- Please indicate your age group

- 20 to 29 years

- 30 to 39 years

- 40 to 49 years

- 50 to 59 years

- 60 to 69 years

- ≥70 years

- Please indicate how you see yourself

- Yellow

- White

- Black

- Pardo

- Prefer not answer

- Please indicate your religion

- Buddhism

- Catholic

- Spiritist

- Evangelical

- Islam

- Judaism

- Umbandism

- Other

- Atheist

- Agnostic

- Please state your marital status

- Single

- Married

- Other

- Please indicate your profession

- Social worker

- Nurse

- Nephrologist

- Resident in Nephrology

- Psychologist

- Other

- Please indicate how long ago have you graduated

- 0 to 5 years

- 6 to 10 years

- 11 to 15 years

- 16 to 20 years

- 21 to 25 years

- ≥25 years

- In which region of Brazil did you graduate in your current profession?

- Midwest

- North

- Southeast

- Northeast

- South

- Other country

- Not applicable

- In which region of Brazil did you specialize in your current profession?

- Midwest

- North East

- North

- South East

- South

- Other country

- Not applicable

- In which region of Brazil do you currently work?

- Midwest

- Northeast

- North

- Southeast

- South

- Other (please specify)

- Please indicate what kind of CKD patient you work with (check what to apply)

- CKD outpatient clinic

- Dialysis Clinic

- Renal Patient’s Ward

- Renal Transplant Service

- Clinic

- Other

- Please indicate the type of institution you work for (check all which apply)

- Private

- Public

- Academic

- Non-academic

- Other

- Please indicate the approximate number of CKD /ESRD patients you see per week

- 0 to 15

- 16 to 30

- 31 to 45

- 45 to 60

- Above 60

- Please indicate the approximate number of CKD / ESRD patients aged 75 years or older that you see per week:

- None

- 1a2

- 3a4

- 5 to 10

- Above 10

- Regarding Renal Supportive Care (RSC), can it be said that…?

- Consider this scenario: An 82-year-old male, a long-standing diabetic patient with advanced diabetic nephropathy (CKD), a sequela of stroke (not ambulatory), severe cardiopathy (EF 25%), and moderated cognitive impairment by vascular dementia is referred for your evaluation.

- If a competent patient asks you to discontinue dialysis treatment how would you deal with this request?

- I would probably stop dialysis

- I would probably continue to dialysis

- I prefer not to answer

- If one of your dialysis patients becomes permanently and severely demented (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia) and has no advance directive, what would you normally do?

- I would probably stop dialysis

- I would probably continue dialysis

- I prefer not to answer

- If you are asked to initiate dialysis in a permanently unconscious patient (e.g., permanent vegetative state or multiple stroke), what would you normally do?

- I would probably not start dialysis

- I would probably start dialysis

- I prefer not to answer

- If one of your patients with a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order suffers a cardiac arrest, what would you normally do?

- I would probably not perform CPR

- I would probably perform CPR

- I prefer not to answer

- Please indicate the degree of importance that the following factors would have on a possible decision not to initiate renal replacement therapy (RRT) but provide comprehensive conservative (non-dialysis) management.

- Is there a Supportive Care or Palliative Care service available at your workplace?

- No

- Yes

- Have you ever worked in any formal Supportive Care or Palliative Care service?

- No

- Yes

- Have you had any exposure or training in Supportive Care or Palliative Care in your professional education?

- No

- Yes

- If the answer was “Yes” to the previous question, what type of exposure or training did you receive (check what to apply)?

- A dedicated course

- A palliative care session at a national congress

- A palliative care session at an international congress

- Internal training at my workplace

- Other

- How often do you evaluate the presence of pain and other symptoms in your patients?

- Never

- Rarely or when reported by the patient

- Routinely

- Prefer not to answer

- How often do you evaluate your patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL)?

- Never

- Rarely

- Prefer not to answer

- How often do you get involved in discussions about end-of-life care with your patients?

- Never

- Rarely Frequently

- I prefer not to answer

- How often do you discuss do-not-resuscitate order with your patients?

- Never

- Rarely

- Frequently

- I prefer not to answer

- In the past 12 months what percentage of patients under your direct care expressed a desire not to initiate dialysis?

- None

- Less than 1%

- 1 to 5%

- 6 to 10%

- More than 10%

- I prefer not to answer

- How many patients with CKD C5 under your care are on comprehensive conservative management (does not include RRT)?

- None

- 1 to 2

- 3 to 4

- 5 to 10

- More than 10

- I prefer not to answer

- In the last 12 months what percentages of patients under your direct care have actually been withdrawn from dialysis?

- None

- Less than 1%

- 1 to 5%

- 6 to 10%

- More than 10%

- I prefer not to answer

- What is your interest in getting or improving your knowledge about Renal Supportive Care

- No interest

- Little interested

- Very interested

- Extremely interested

- Please rate how helpful this questionnaire was to you.

- Not useful

- A little useful

- Very useful

- Extremely useful

- Would you have any suggestions or comments on how to improve Renal Supportive Care in Brazil?

Thanks for participating!

Acknowledgements

We would like thank Ms. Priscila Jacovani from Follow55 for sending the e-mails and all members of the Brazilian Society of Nephrology who responded to the survey. This survey was supported by the Brazilian Society of Nephrology in sending e-mails to members of society, data collection and statistical analysis.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Americas Serviços Médicos located in Hospital Pro-Cardíaco, Rio de Janeiro, protocol number 2.058.501 and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013;382:260-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown SA, Tyrer FC, Clarke AL, et al. Symptom burden in patients with chronic kidney disease not requiring renal replacement therapy. Clin Kidney J 2017;10:788-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Higginson IJ. The prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: a systematic review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2007;14:82-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;31:58-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative Care for the Seriously Ill. N Engl J Med 2015;373:747-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Almutary H, Bonner A, Douglas C. Symptom burden in chronic kidney disease: a review of recent literature. J Ren Care 2013;39:140-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, et al. Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:960-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US Renal Data System 2016 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2017;69:A7-A8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information: Canadian Organ Re- 2015 placement Register Annual Report: Treatment of End-Stage Organ Failure in Canada, 2004 to 2013, 2015. Available online: https:// secure.cihi.ca/free_products/2015_CORR_AnnualReport_ENweb. pdf, accessed February 9, 2017.

- Sesso RC, Lopes AA, Thomé FS, et al. Brazilian Chronic Dialysis Survey 2016. J Bras Nefrol 2017;39:261-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, et al. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1539-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, et al. Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1611-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, et al. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: Comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:1608-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morton RL, Webster AC, McGeechan K, et al. Conservative Management and End-of-Life Care in an Australian Cohort with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:2195-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, et al. CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: Survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:260-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Biase V, Tobaldini O, Boaretti C, et al. Prolonged conservative treatment for frail elderly patients with end-stage renal disease: The Verona experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:1313-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yong DS, Kwok AO, Wong DM, et al. Symptom burden and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: A study of 179 patients on dialysis and palliative care. Palliat Med 2009;23:111-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO Controversies Conference on Supportive Care in Chronic Kidney Disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int 2015;88:447-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Germain MJ, Kurella Tamura M, Davison SN. Palliative care in CKD: the earlier the better. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;57:378-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Combs SA, Davison SN. Palliative and end-of-life care issues in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2015;9:14-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res 2004;6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:549-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yee A, Seow YY, Tan SH, et al. What do renal health-care professionals in Singapore think of advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease? Nephrology (Carlton) 2011;16:232-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luckett T, Spencer L, Morton RL, et al. Advance care planning in chronic kidney disease: A survey of current practice in Australia. Nephrology (Carlton) 2017;22:139-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feldman R, Berman N, Reid MC, et al. Improving symptom management in hemodialysis patients: identifying barriers and future directions. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1528-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Biesen W, van de Luijtgaarden MW, Brown EA, et al. Nephrologists' perceptions regarding dialysis withdrawal and palliative care in Europe: lessons from a European Renal Best Practice survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015;30:1951-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holley JL, Davison SN, Moss AH. Nephrologists' changing practices in reported end-of-life decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:107-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parvez S, Abdel-Kader K, Pankratz VS, et al. Provider Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Surrounding Conservative Management for Patients with Advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:812-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rutecki GW, Cugino A, Jarjoura D, et al. Nephrologists’ subjective attitudes towards end-of-life issues and the conduct of terminal care. Clin. Nephrol 1997;48:173-80. [PubMed]

- Lobo SM, De Simoni FHB, Jakob SM, et al. Decision-making on Withholding or Withdrawing Life Support in the ICU: A Worldwide Perspective. Chest 2017;152:321-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mark NM, Rayner SG, Lee NJ, et al. Global variability in withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:1572-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yaguchi A, Truog RD, Curtis JR, et al. International differences in end-of-life attitudes in the intensive care unit: results of a survey. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1970-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lago PM, Piva J, Garcia PC, et al. Brazilian Pediatric Center of Studies on Ethics: End-of-life practices in seven Brazilian pediatric intensive care units. Pediatr Crit Care 2008;9:26-31. [Crossref]

- Forte DN, Vincent JL, Velasco IT, et al. Association between education in EOL care and variability in EOL practice: a survey of ICU physicians. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:404-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moura JA. Neto, Moura AFS, Suassuna JHR. Renouncement of renal replacement therapy: withdrawal and refusal. J Bras Nefrol 2017;39:312-22. [PubMed]

- Markwell HJ, Brown BF. Bioethics for clinicians: 27. Catholic bioethics. CMAJ 2001;165:189-92. [PubMed]

- Sprung CL, Maia P, Bulow HH, et al. The importance of religious affiliation and culture on end- of-life decisions in European intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:1732-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fumis RR, Deheinzelin D. Respiratory support withdrawal in intensive care units: families, physicians and nurses views on two hypothetical clinical scenarios. Crit Care 2010;14:R235. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ganguli I, Chittenden E, Jackson V, et al. Survey on Clinician Perceptions and Practices Regarding Goals of Care Conversations. J Palliat Med 2016;19:1215-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ying I, Levitt Z, Jassal SV. Should an Elderly Patient with Stage V CKD and Dementia Be Started on Dialysis? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;9:971-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van de Luijtgaarden MW, Noordzij M, van Biesen W, et al. Conservative care in Europe-nephrologists' experience with the decision not to start renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:2604-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tamura MK, O'Hare AM, Lin E, et al. Palliative Care Disincentives in CKD: Changing Policy to Improve CKD Care. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;71:866-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Welie JVM, ten Have HAMJ. The ethics of forgoing life-sustaining treatment: theoretical considerations and clinical decision making. Multidiscip Respir Med 2014;9:14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Holley JL, et al. Nephrologists’ Reported Preparedness for End-of-Life Decision-Making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;1:1256-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cervantes L, Linas S, Keniston A, et al. Latinos With Chronic Kidney Failure Treated by Dialysis: Understanding Their Palliative Care Perspectives. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;67:344-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cervantes L, Jones J, Linas S, et al. Qualitative Interviews Exploring Palliative Care Perspectives of Latinos on Dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:788-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kizawa Y, Morita T, Miyashita M, et al. Improvements in Physicians' Knowledge, Difficulties, and Self-Reported Practice After a Regional Palliative Care Program. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:232-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang HL, Yao CA, Hu WY, et al. Prevailing Ethical Dilemmas Encountered by Physicians in Terminal Cancer Care Changed after the Enactment of the Natural Death Act: Fifteen Years Follow up Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:843-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Bausewein C, Reilly CC, et al. An integrated palliative and respiratory care service for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:979-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Available online: http://paliativo.org.br/ancp/onde-existem/, accessed in January 14, 2018.

- de Heer W. International Response Trends: Results of an International Survey. J Official Stat 1999;15:129-44.

- Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Lomas J, et al. Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care 1999;11:187-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]