Perspectives of patients, family caregivers and health professionals on the use of outcome measures in palliative care and lessons for implementation: a multi-method qualitative study

Introduction

Measuring patient and caregiver outcomes can improve the quality and efficiency of care (1-3). In palliative care, there is increasing use of outcome measurement in routine practice (4-7). Implementation of outcome measures has been associated with changes in care processes including: better symptom recognition, more discussion of quality-of-life and increased referrals (3). A recent European Association for Palliative Care white paper (8) recommended the implementation of outcome measures to: improve awareness of unmet needs; understand different models of care delivery; and allow for national and international comparison.

Despite the growing emphasis on use of outcome measures in palliative care, less attention has been paid to the implementation of these measures in clinical practice (3,9). Previous studies have identified potential facilitators and barriers to implementing outcome measures in palliative care (9,10) and highlighted an urgent need for training and support for their use (3,11).

The Outcome Assessment and Complexity Collaboration (OACC) project was designed to support the implementation of outcome measures in specialist palliative care in the UK (12). The OACC suite of measures includes measures that are completed by patients, caregivers and staff. The core measures include phase of illness (4,13,14), modified Australian Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) (15), Integrated Palliative care Outcomes Scale (IPOS) (6), Views On Care (16), and caregiver burden (17). Phase of illness and AKPS are staff-completed measures, whilst IPOS can be completed by patients, family or staff. Patient-centred outcome measures (PCOMs) are validated tools completed by patients, or proxies, which capture patients’ symptoms and well-being. The use of ‘patient-centred’ rather than ‘patient-reported’ outcome measures is particularly useful in palliative care where often patients have impaired cognition, or are too unwell to complete the measures themselves (3), proxy-completed measures have previously been found to be a fair substitute to patient response for assessing symptoms and quality-of-life (18-20). Learning from other work on facilitators to implementing outcome measures (9), the OACC project included an educational and feedback component. Ongoing support was provided directly to staff at various stages of implementation (dedicated Quality Improvement Facilitator, print and digital training materials, and regular webinars). The aim of this study was to explore how patient-centred outcome measures are used in specialist palliative care, and identify key considerations for implementation.

Methods

Design

Multi-method qualitative study using semi-structured interviews and non-participant observations.

Setting

Nine specialist palliative care services in South London (UK), including one in-patient hospice, five hospital and three community teams.

Participants

Sampling

Participants were purposively sampled across the nine services. Staff participants were sampled by profession (doctors, nurses, allied health professionals) and experience of using the OACC measures. Eligible patients and family caregivers had to be over 18 years of age, speak English, well enough to take part in an interview (as judged by their clinical team), and be receiving specialist palliative care at the participating service. Potential patient participants were approached by their clinical teams; if they were not deemed well enough to undertake an interview, they were not approached. We anticipated that the majority of PCOMs used in the OACC project would be staff-completed measures. Therefore, we over-sampled health professionals to elicit more experiences.

Recruitment

Patients and family caregivers were initially approached by the clinical teams; those who agreed to further contact were then approached by a researcher (C Pinto/J Witt). Eligible staff participants who were willing to participate in the interview or observation were approached directly by the researcher (C Pinto/J Witt). All eligible participants were given an information sheet and had an opportunity to ask questions. All participants gave written informed consent before the interview or observation. Data was collected from December 2014 to November 2015.

Data collection

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews ensured exploration of a pre-determined set of issues whilst allowing the researcher to probe in more depth. The interview guide was informed by the domains in the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (21), a widely used framework that offers a comprehensive consideration of implementation issues. Two patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives were involved in the development of information sheets and interview guides. Interviews focused on the benefits, challenges and implementation issues (see Figure S1,S2,Table S1).

Full table

C Pinto, J Witt and S de Wolf-Linder conducted interviews either in clinical settings (wards or offices) or at home, based on the participants’ preference. All interviews were audio recorded; researchers kept field notes to capture contextual information. Data collection continued until saturation of themes was reached.

Non-participant observation

Non-participant observations with staff were undertaken to supplement the interviews. C Pinto and J Witt carried out the observations after obtaining participant consent. Where observations involved interaction with other people (staff, patients, family members), individuals were given the opportunity to refuse being observed. Detailed field notes were used to record observational data.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim. Analysis of data was undertaken using Framework analysis (22,23) (supported by NVivo software) as it allows exploration within and between cases and themes and is well suited to addressing specific policy questions (23). The CFIR informed our data analysis framework. Framework analysis allowed us to compare important themes emerging across the CFIR domains and different participant groups.

A coding tree was developed after familiarisation and inductive line-by-line coding of a few interviews. These codes were then systematically applied to the data (indexing). Data were then summarised into a matrix and different categories of codes grouped together within separate charts (charting). Emerging themes and divergent perspectives were explored. Rigour was established by discussing and comparing analyses between project team members (CP/CS/KB/FEM) and following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (24). Analysis of the observations was undertaken concurrently using the developed coding tree and triangulated with the interview findings.

Ethics

Ethical Approval for the study was granted by the UK National Research Ethics Service (Committee: London-Bromley 14/LO/1669); all procedures followed were in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki (25).

Results

Participants

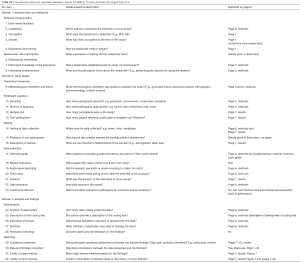

Thirty eight participants were interviewed (39 approached): 7 patients, 4 family caregivers, 11 doctors, 8 nurses, and 8 allied health professionals (see Table 1). The median duration of interviews was 50.5 minutes (range: 15–107 minutes). Nine observations with 6 nurses and 3 doctors were undertaken (3 in the community, 5 in a hospital and 1 in an in-patient hospice).

Full table

Findings

Findings are presented according to the five CFIR domains: (I) intervention; (II) outer setting; (III) inner setting; (IV) individual; and (V) implementation. Main themes and subthemes are illustrated in Figure 1.

Intervention

Three subthemes emerged from participants’ views on PCOMs as an intervention: advantages, disadvantages and appropriateness of using PCOMs in specialist palliative care.

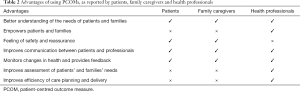

Relative advantages of using PCOMs

The advantages reported by participants are summarised in Table 2.

Full table

(I) Better understanding of the needs of patients and families

Patients, families and professionals described PCOMs as a way for staff to better understand the main problems and issues faced by patients and families.

“For the patients I think it’s really good that they feel that they’re being heard. That straight away they’ve got an opportunity to tell us what their main problems are, to tell us what symptoms they’ve been experiencing physically, tell us about their mood, and how they perceive their family situations to be, and the problems and issues that they have” (08009, palliative care nurse).

Patients and family caregivers also viewed PCOMs as a chance to inform staff about their concerns. For some, changes in care were attributed directly to completion of PCOMs.

“…for instance, if a nurse came back to you and said, ‘Well, you know, when don’t you feel at peace?’…it opens up a conversation then, and would perhaps help someone who’s not dealing with themselves so well.” (08002, patient).

“I was offered a pump infusion of anti-sickness drugs, which came directly out of this [PCOM] … I think I found them helpful and I got help because of them. So, yes, I think they’re a good idea.” (01006, patient).

(II) Empowers patients and families

Professionals described the use of PCOMs as redistributing power, giving the patient more control over their care decisions.

“I think it gives the patient a voice, which is important…people being able to fill out and that, it just gives them a…kind of autonomy and they feel that they’re taking more of a kind of role in their care, which I think is always a pretty good thing.” (01001, palliative care doctor).

PCOMs can also empower family caregivers, giving them the opportunity to contribute to the patient’s care and validating their concerns alongside those of the patient.

“I should think carers would complete those as well (caregiver questions), yes, because they feel it’s an additional part of helping whoever they’re caring for, whether it’s the husband, wife, auntie or uncle.” (03002, palliative care nurse).

“I think with the Zarit carer interview [tool to measure caregiver burden] the positives are that it could make the carer aware that your team is looking after them as well as the patient and they could find some benefit in that.” (05003, palliative care nurse).

(III) Feeling of safety and reassurance

Some patients and family caregivers described reassurance from completing a PCOM, knowing that the symptoms listed on the PCOM were common/recognised, and that the completed PCOM would be reviewed by staff.

“I think it was nice that somebody had come up with a list of all the things I was feeling. I recognised all of the symptoms on the list immediately as being those that are commonly experienced by patients going through a rough time in hospital. It wasn't just me, these were typical. So that, in a way, was a reassurance up front that what was happening to me was common to other patients…It was also nice that somebody was interested in gauging how severe they were with a view to actually being able to help me.” (01006, patient).

“Well, I think at the time it probably made me feel that there’s an opportunity that somebody’s going to listen.” (08002, patient).

(IV) Improves communication between patients and professionals

Both patients and professionals described PCOMs as aiding communication by opening up discussions and prompting further assessment, particularly around psychological issues.

“Because quite often if somebody has ticked that they’re always anxious, or they’re always worried, or they’re always feeling depressed, it really triggers us, especially on ward round but at other times as well, to actually really assess their mental health, and really assess how they’re coping psychosocially. That’s been really helpful as well.” (08009, palliative care nurse).

“…it would help prompt other patients so they’re not perhaps in the space that I’m in. I mean, for instance, if a nurse came back to you and said, ‘Well, you know, when don’t you feel at peace?’, it opens up a conversation then, and would perhaps help someone whose not dealing with themselves so well.” (08002, patient).

(V) Monitors changes in health and provides feedback

PCOMs were described as providing valuable objective feedback to the patient, family and staff, enabling them to see change and stability when facing deteriorating health.

“I think, having them all on this piece of paper listed, helped me put them into context and made me realise that I was just being overwhelmed and overrun with all sorts of nasty side effects. These were well known ones and it can be dealt with.” (01006, patient).

“I think they’re quite necessary now, to prove what we’re worth and what we’re doing, and as a way of evaluating if our treatment is effective, and our input to patients is effective, and either to be able to help patients and improve what we do for patients on an individual basis, and also more nationally, I suppose.” (080011, allied health professional).

(VI) Improves assessment of patients’ and families’ needs

Professionals described the positive impact of PCOMs on the structure of their assessment and documentation, enabling a quick summary of the patient’s main problems and concerns.

“I think it’s a really nice holistic tool, because it actually gives us a bit of everything… especially if there’s an overwhelming physical symptom, especially one that’s quite hard to control, sometimes as a medical and nursing team we can get quite blindsided and focused by that. This gives us a chance to actually step back and think. There are other things going on. We can’t get so focused on this one really troubling, very obvious symptom, and forget that this person has a lot of other dimensions that they’re dealing with, and a lot of other domains that they’re going through.” (08009, palliative care nurse).

(VII) Improves efficiency of care planning and delivery

Additionally, PCOMs were used to increase the efficiency of team working, supporting prioritisation and triage, prompting and focusing clinical discussions, and facilitating familiarisation with individual cases.

“…often the way people are referred you get referrals that are way too early and referrals that are way too late. Sometimes, having that information about how people are performing with their different illnesses might actually help with how people are referred to services and how they’re responding.” (09001, palliative care nurse).

From the observational data, PCOMs were not necessarily always being used in this manner across the participating sites, but there was recognition of this potential utility.

“Normally at MDT reviews, we give a summary of the patient and their diagnosis and their circumstances, their family and social issues, and then try to focus in on the particular needs, concerns of the time, and I think if we use the IPOS it will help us focus and perhaps see things that we might not have commented on otherwise.” (02001, palliative care doctor).

“I think the way they use it here in MDMs is probably a good thing to be taken forward, so you’re checking that what you’re doing is helping and if not, does that raise alarm bells that maybe someone else should be getting involved and should you be thinking about something different.” (06003, palliative care doctor).

Health professionals recognised the value of PCOMs for service provision and audit, improving understanding of the needs of the local population, and demonstrating the value and contribution of the service.

“…it may be able to use to see if you’ve got adequate resources to meet your patient group as well, it goes back to the funding a little bit, a way of looking at your service and looking at potentially using it for business case preparations.” (03001, palliative care doctor).

Relative disadvantages of using PCOMs

The disadvantages reported by participants are summarised in Table 3.

Full table

(I) Increases patient burden

A concern frequently raised by staff was the potential additional burden of completing PCOMs for patients and caregivers.

“… the other one that people are bound to say is the burden of asking patients or carers too many questions and outcome measures … they’re vulnerable, they want to please us so they’ll answer them. They’re burdened too heavily by it all, well I think carefully used and appropriately used, if it’s approached in the right way, patients and families are keen to help…” (08005, allied health professional).

Patients and family caregivers did not describe PCOMs as burdensome, but stressed the importance that they should support, not replace a discursive approach.

“Maybe instead of when they give the paper to me, maybe they should have, if you have questions that you can’t answer, maybe you can get in touch with so-and-so, they would be able to put you through. If, when they give it out, they say, “Okay, if there is any question that you feel you can’t answer - if you have any question that you don’t understand, maybe you can get in touch with this, or you get in touch with this, so they will be able to explain it better.” (08008, patient).

“I think, if the patient needs help with controlling the side effects of their treatment, most patients would be very glad to fill in a form if it gathered the right information to enable that to happen. I certainly was. I don't see how anybody would object to that, unless they were too ill to fill the forms in.” (01006, patient).

(II) Patients too ill to complete

Participants highlighted the challenges of using PCOMs in the context of deteriorating health because of patient ill-health, communication difficulties or cognitive impairment. Findings from the observations corroborated this.

“…because my husband can no longer write and is often confused, I frequently helped him with it and ticked the box where it said ‘Did you do this yourself or did somebody help you?’ He hasn’t ever completed one on his own.” (08007, family caregiver).

“I think it’s also really nice that we can do a staff version. Because we have quite a few patients, obviously, who come in and they’re already really poorly or they’re already semi-unresponsive.” (08009, palliative care nurse).

(III) Time-consuming nature

Staff also raised concerns about the added time required to complete PCOMs, particularly in the face of staff turnover or shortages.

“The difficulty is when we’re really busy, and we are busy a lot of the time, and once we’ve got a member of staff absent the workload becomes virtually unmanageable, and so then it becomes a little bit of an extra burden, so it depends very much on our busy-ness and our staffing levels as to how well we cope with it. I suppose one of the concerns is that if you’re very busy and you do it very quickly, then it may not be that accurate, and I suppose that would be a concern, as well as the fact that it’s time consuming.” (02001, palliative care doctor).

Observational data showed the importance of IT systems being setup to support PCOM completion, with integration within the electronic patient records to enable quick completion.

(IV) Could hinder accurate, holistic assessment of needs

The prescriptiveness of PCOMs was a barrier for some staff, forcing them to think of patients as a homogenous group, to the exclusion of individual experiences.

“Well if the outcome measures are too prescriptive then people will start only asking about those questions. So if there’s a symptom that’s not on the list and people get too blinkered with the outcome measures, they will stop asking about other things. Or if outcome measures become the only thing that’s important, then the more holistic nature may be lost.” (07003, palliative care doctor).

Staff also recognised that PCOMs are not comprehensive, highlighting the importance of using them alongside, not instead of, holistic assessment.

“…there is nothing in there about swallow. And also, the other part of my work is communication. So there is nothing in any of these about swallow or communication …the ability to eat and also the ability to communicate—all of these issues, aren’t covered. So that makes it very difficult to, kind of, document that.” (080014, allied health professional).

(V) Not responding to the information collected

Patient participants stressed that the value of PCOMs is dependent on the data being utilised to improve their care.

“I think forms are at their worst when you're asked to fill them in and then nothing happens. It just becomes a collection of information that's not acted upon. I think the key to a good form is, it's short, it gathers the information easily and quickly and it's then followed up and acted upon. That happened in my experience with these two forms. Hopefully, it will continue to do so across the rest of the hospital, if needed.” (01006, patient).

Meanwhile staff reported concerns that completing PCOMs could raise concerns that are beyond the resources of the service.

“I think it can perhaps lead to sometimes false expectations as well, that we are gathering this information, but what do we do with the information? Can we provide the support for them at the end of the day anyway…If there aren’t the resources in the community to address some of the concerns, some of the problems.” (06001, allied health professional).

“I just think maybe a service that’s looking at its data regularly, using data like this and exploring it, would be considered to be a better service because you’re able to reflect on the data that you have. I think the bit that we’re missing is the adequate data collection and the space to reflect.” (05002, palliative care doctor).

(VI) No advantage or disadvantage to care

Some participants felt there was no added value provided by PCOMs—that they did not change the holistic assessment.

“It’s information that we collect but I don’t think it informs clinical decision making for an individual patient as much as it could potentially.” (07003, doctor).

“I think the care is consistent and it's good and it would be so even if these forms didn't come round. I just thought that they were there for statistical purposes and to improve the way they look at things.” (08007, family caregiver).

“Yes because I guess a lot of the stuff on here are questions they would be asking, patients, anyway around pain, breathlessness, appetite, constipation, how they are affecting them at the moment, how they have affected them. The anxiety, how the family are feeling, psychological stuff. These are all questions that the CNS’s and myself would usually ask patients.” (06001S, allied health professional).

Appropriateness and validity of PCOMs in specialist palliative care

Professionals emphasized the need to select PCOMs that are appropriate and validated for use in palliative care.

“Well, I was very interested to discover that actually outcome measures had been used for quite some time in Australia, and they’d been developing them over a number of years… But because they have done, we can see the benefits of it, and I guess that’s partly why we’re doing it, because there’s a national need to do it here. But also because there’s a precedence which is positive.” (02001, palliative care doctor).

“I think there’s some value that it’s been done with the [organisation], because that’s meant to be the focus on the values of palliative care.” (09002, allied health professional).

Some professionals felt that, within palliative care, PCOMs had limited value for demonstrating improvement as patients may become more symptomatic. Others valued PCOMs to demonstrate the difference made by palliative care to patients facing deteriorating health.

“My understanding is that it’s going to benefit the hospice such that we can prove to funders, “Actually, yes, all our patients die, because that’s what palliative care is, but we are having a significant impact.” Our service is having a significant impact on the wellbeing of the carers, and the wellbeing of the patients, and their quality of life, and their levels of anxiety, and depression, and their symptoms, as well as their physical symptom control.” (08009, palliative care nurse).

Outer setting

Participants described the influence of factors outside the organisation (21) upon the use of PCOMs in practice, including policy and national drivers towards mandating the use of PCOMs.

“So I think they’re (NHS policies) the main drivers for using all of this, which will be an introduction of national tariffs and funding and comparative league tables to compare different services, what they offer, what they don’t offer.” (07003, palliative care doctor).

“I think, far more importantly, we have seen their place in a much bigger strategy of looking at what happens in palliative care, so developments in funding and developments in the way that palliative care is supported and looked at and so on, and how this fits into all of that picture. So I think in that sense, it’s been a very useful, helpful thing, and I think if somebody had just landed here and gave us this questionnaire, and said, ‘Speak with this,’ it would have felt very different.” (08003, palliative care doctor).

Others expressed concerns around PCOMs being used to ration funding (rather than demonstrate palliative care contribution or need), leading to changes that will not match the realities of day-to-day practice or may negatively impact on patients.

“My suspicion remains that trying to put numbers against care is about funding and that that can be manipulated in different ways. We can have a very good outcome measure, but if that’s attached to inadequate ways of funding then that is still going to have a negative impact for patient care.” (04002, palliative care nurse)

Inner setting

Participants described the impact of the structural, political and cultural context of organizations on the use of PCOMs.

IT infrastructure

Provision of resources and infrastructure to support the implementation and use of PCOMs was deemed important, including embedding PCOMs into existing IT systems to avoid duplication of work. Findings from the observations also confirmed this. When documentation was streamlined with prompts, staff completed PCOMs more easily. Administrative and data management support were also necessary to manage day-to-day concerns and promote PCOM usage.

“I think the way that the outcome measure we’ve been using and the way in which we’ve been recording them, because of our data system, that has been quite straightforward and quite easy to do, which I think is the main reason why it has actually been happening …” (03001, palliative care doctor).

“So having data managers, I think there’s a bigger awareness in all teams that management of data is important. But this is, I think about capturing data as much as anything and tracking it. Yes, I think it would be really helpful to have that, but of course everyone will say that and there’s no money for that.” (07003, palliative care doctor).

Healthcare environment

Participants identified barriers to PCOM use within certain healthcare settings, including service caseload and availability of private spaces for PCOM completion, which may raise emotional issues.

“I think the main disadvantage in a hospital is the patients being so sick often, so fluctuant and with so many demands on them. They’ve got lots of professionals seeing them, they’re already quite ill, their day is very busy and they get to see lots of people … I’ve often taken both these kinds of assessments and others to the patient, said ‘Can you fill it in and I’ll pick it up tomorrow?’ and it’s lost or they haven’t had enough energy to do it. They can’t focus on it, actually.” (01003, palliative care nurse).

“It’s usually away from my mother. This part, I can do it, but this part, I don’t want her to know. Yes, if we are very stressed, I don’t want her to know.” (01005, family caregiver).

Observational data showed that availability of computers in the care setting influenced when staff-reported PCOMs were completed. If they were unavailable or not integrated into wider hospital records, this resulted in a delay, difficulty or non-completion of PCOMs.

Utilisation of PCOMs in daily clinical interactions

Professionals shared the importance of bringing PCOMs into day-to-day team interactions. This was also echoed in the observations where staff integrated PCOMs into handover and team discussions to summarise and flag important information about patients.

“So for instance, in MDT [multidisciplinary team] meetings, it definitely flags up need. Need for support and… So for instance, pain, if you saw a number four, even as a therapist, even though that’s not my area of speciality, I would be raising—I would be looking for that and raising that with the people who are managing that. So I would be raising that with the medical team. If the patient—if I saw that they had a very poor appetite, I would be liaising with the dietician about that. So this would guide me to share information with the appropriate people.” (08014, allied health professional).

“We have our ward round on a Monday, and when we go into ward round we always, for every patient, look at their most recent OACC, which I think just makes it really clinically relevant.” (08009, palliative care nurse).

Team working and peer support

Professionals described the impact of the culture of the multidisciplinary team on implementation of PCOMs. Barriers included high staff turnover or when negativity or mistrust emerged regarding PCOMs.

“I find that getting people on board is really important. And one of the ways that I found that best works, is actually sitting people down as a team, in teams. So it could be a multidisciplinary team, it could be in wards, it could be in therapies, in nursing, in different professions. But actually, talking about it and having the support, and doing it together.” (08014, allied health professional).

“…there’s no doubt that if you get a negative view from within a team about feeling that outcome measures are of no great value, then you know that negative views often spread much more quickly than positive ones. So, it’s about yes, maintaining morale and relationships, in order to prevent negativity…” (02001, palliative care doctor).

Participants described the importance of distributing responsibility among all team members in the implementation and use of PCOMs.

“I think it’s really important to be bringing everyone with you. There are a lot of staff who don’t have a clue about OACC and won’t look at it or use it because they weren’t brought in on it from the beginning. Assessments are traditionally seen as a nursing role here. Then, when you identify, according to IPOS, someone’s symptoms, you might refer on to Physio, Occupational Therapy, Complementary Therapy or the Arts team.” (08010, allied health professional).

Supportive leadership

Another critical element was support through leadership—senior staff and managers, actively participating in the implementation and use of PCOMs.

“I think that if you’ve got managers reminding us that it’s important, checking up whether people are doing it, and that are involved with it as well. Engaged with it rather than going, “Whatever”, I think it makes a difference, definitely.” (06002, palliative care nurse).

This supportive role needed to include understanding and communication of the benefits of PCOMs at individual, service and institutional levels.

“But leadership within the organisation, you know, from the CEO’s to the consultants on the wards, to the nurse managers, all of them need to be very positive about what it’s about and why it’s important and valuable.” (08005, allied health professional).

“I think you have to be someone who is respected by your team, if you’re going to give them more work to do, then they have to like you. So I think earning respect and being seen as a good example, I think are the qualities, and understanding where their difficulties are coming from, so having some empathy.” (02001, palliative care doctor).

Individual

Knowledge and competence

Professionals described the benefits of knowledge about the specific PCOMs and their components, and the rationale for using them.

“I think firstly, clearly, people need to understand why they’re being done, why they are the way they are … They need a bit of training in how to use them. They need support if there are any problems, and there needs to be a kind of encouragement and use of them.” (08003, palliative care doctor).

“ … I didn’t feel it was really explained to us how it was going to be operating. It wasn’t really explained to us what the purpose was. It was partly and maybe I just switched off … I didn’t feel that I really understood why it was being introduced, what it was for, exactly how to operate it.” (08001, palliative care doctor).

Professionals also discussed the importance of training to integrate PCOMs alongside regular clinical assessments.

“I think that they just need to be trained in the best way to ask the questions, to get the information. I think if it comes out as a bit of a check list of questions to go through, without it coming freely in speech and then in assessment, then it could come across like you are just asking some tick box question, rather than just covering all these things in a conversation. I think it would just be about having the training and knowing what information you’re trying to get out, without being clinical with the questioning?” (06002, palliative care nurse).

“So I think training is really, really important, because if we actually want to get accurate recording, we have to hear the answers and we have to know how to record that. But we also need to reflect on who do we refer to and what is normal, or what we think, “Oh my God, that’s a whole can of worms,” or, “I’m going to say the wrong thing,” which is what the staff say, that their worst fear is that they’re going to make it worse by asking these questions.” (09002, allied health professional).

Participants valued the training provided by the Quality Improvement Facilitators from the OACC team, particularly training as a team, which enhanced knowledge and promoted a supportive environment for implementation.

“…it was quite a while ago but I do remember being quite interested in it. There was quite a discussion at the time, whenever the training was being done … it did throw up a lot of questions from the group… I think that was important because it gave us that understanding of what was going to happen and why it was happening and what we were hoping to achieve, and … doing it accurately … but it gave us that opportunity to talk about it, ask, throw up those questions …” (07001, palliative care nurse).

Attitudes towards using PCOMs in clinical practice

Professionals had reservations about using PCOMs to shape care delivery, feeling they were at odds with the ‘culture’ of palliative care—‘it is not what we do’.

“Well, I think it requires, as we’ve discovered, constant retraining and constant re-embedding to get it into routine practice. I think staff currently see it as a burden and an extra task which they don’t want to do, partly because they’re not used to using them. It’s not part of our culture, particularly.” (05002, palliative care doctor).

However, some felt that the measures were in line with the palliative care ethos:

“Yes, I find it really helpful. I like the focus on symptoms. I think that’s really helpful. Because I think question one is very reflective of palliative care ethos, and I like the fact that it’s question one. That we don’t dive straight into just a symptom checklist, but actually we first ask, holistically, ‘What have been your main problems?’ So I found it really helpful.” (08009, palliative care nurse).

Professionals were concerned about the consistency of PCOM use within the team, particularly with measures that could be either patient or proxy-completed. Observational data also showed inconsistencies in how and when staff completed PCOMs.

“I think obviously there is a few different versions which could become quite overwhelming if you’ve got patient’s, relatives and the staff version, so it becomes a bit confusing what version we’re giving to who, what we’re doing, type of thing.” (02003, palliative care nurse).

Implementation

Finally, participants considered the necessary and sufficient processes for successful implementation of PCOMs.

Stepwise introduction of PCOMs

For many, a stepwise implementation (used by the OACC project) provided a manageable way to integrate PCOMs with regular clinical practice.

“It’s made something that would otherwise I think be completely unmanageable more manageable. I think there would have been dare I say, a revolt in the camp if we had been asked to do everything at once, that there would have been a downing of tools and a ‘no we’re not’…But because of introducing it in a stepwise manner, that has helped, definitely. Definitely.” (02001, palliative care doctor).

However, some were hesitant about this approach feeling it concealed the total number of PCOMs that are going to be introduced and this should be transparent at the outset.

“It’s a tiring process, change management, and if you’re constantly adding another bit of paper and another page to what you’re doing, and then another page to what you’re doing, I think the staff tire of it. Whereas if you can be really honest with them, and say, ‘This is a big project. We’re going to just jump in.. This is what it involves. It’s these four or five things that we need to do.’… I think being transparent and going for it is the only way to do it.” (08009, palliative care nurse).

“I think although it’s a lot to do in one go, I suspect it is more effective. Because to staff on the ground who are filling in the measures it’s that ‘Oh, it’s changed again. Oh, it’s the new month, so we’ve got to do the new measure Oh gosh, it’s changed again.’ So I think if it’s all done in one big hit it’s probably better.” (08011, allied health professional).

Feedback sessions

Regular feedback was essential to engage and motivate team members, and demonstrate the relevance of PCOMs. Bespoke service-level feedback was particularly valued.

“I actually found it quite helpful when they came and were showing us the usage and what the data was beginning to show. That was quite interesting, because obviously it does show you that it’s not purely a paper exercise in terms of what the outcome is being used for, and I think that gives people more… They understand the strategic importance of it, which is good.” (09001, palliative care nurse).

“…when we get the feedback of what it shows in the patients, the staff then think, oh well that’s been worth demonstrating, how many patients have been deteriorating, are unstable or what percentage was the Karnofsky - how many of our patients are below 30% …so it actually shows you the amount of… quite seriously ill patients that you do see as well in hospital.” (02001, palliative care doctor).

However, there were missed opportunities to share learning across sites, and more frequent feedback would have been appreciated.

“I think regular feedback will keep people doing it. I guess some of that could be in verbal feedback and others could be in email feedback, because we’re not always going to get the verbal regularly, and not everyone’s always here.” (06002, palliative care nurse).

Champions and facilitators

Professionals also highlighted the importance of local champions within the team, and regular contact with the quality improvement facilitators (QIFs), to promote and sustain PCOM use.

“I think what’s helpful to be honest is when sometimes they [QIFs] do say about other teams that are struggling with some of the same issues because then you feel that you’re not the only team, and so that’s helpful, and yes, just presenting some of the data. They’re I think supportive in a way of being gently encouraging, without force, dare I say. Very encouraging, I think that’s the thing that we would all say, is they come enthusiastic and encouraging, then also sympathetic to the difficulties and pressures, and understanding of that.” (02001, palliative care doctor).

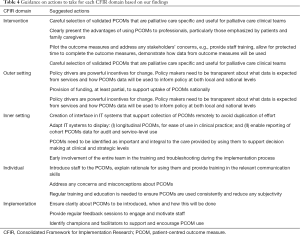

Overall recommendations for implementing PCOMs in practice are shown in Table 4.

Full table

Discussion

We used the CFIR to highlight key considerations for implementing outcome measures in palliative care. A central theme across all CFIR domains was the importance of demonstrating how PCOM data were fed back and used to improve care.

In our study, participants stressed that the data from PCOMs needs to be used directly to improve patient care. Perceptions were positive if PCOMs were used in daily clinical interactions and perceptions were negative if there was no response to data collected from PCOMs. Other studies have also stated the need for more evidence of the impact of providing information from outcome measures to clinicians to improve patient care (26,27). The perception of relevance to clinical practice is an important factor among health professionals when implementing outcome measures (10,28), and evidence suggests the importance of making that explicit by integrating PCOMs into existing clinical information and decision making processes (27). For example, one study used patient-reported outcomes to estimate where patients with advanced cancer were along their disease trajectory and recommend appropriate levels of treatment (29).

A novel finding is that patients, family caregivers and health professionals valued the objective feedback from PCOMs, even in the face of deteriorating health. This further validates the need to use PCOMs in palliative care settings.

We found important similarities and distinctions between patient, family caregiver and professional perspectives on using PCOMs in specialist palliative care. Participants agree that PCOMs support better recognition of patients’ needs and improve communication; this finding resonates with existing work (2,3,30,31). In addition, patients in our study reported feeling safe and reassured as a benefit of using PCOMs.

Previous studies described PCOMs as time-consuming and adding to patient burden (9-11). However, in our study patients and family caregivers did not report patient burden. Our findings corroborate those of previous studies (3,18) that palliative care patients may be too ill to complete PCOMs. There is an important distinction between patient burden and patients being too unwell to complete outcome measures – these are often conflated.

Strengths and limitations

Professional participants were purposively over-sampled to reflect the balance of patient and proxy-completed measures. We were unable to recruit enough patient participants, especially in the community setting, to achieve saturation. This was in part because it took some time for outcome measures to be used with potential participants; they had often then become too ill to undertake an interview (or had been admitted). In future, undertaking this research in units where outcome measures are already implemented (rather than where implementation of outcome measures was also an aim) would be a useful addition to the evidence base.

We collected data at different stages of a stepwise implementation process, which may have influenced the findings. Outcome measures were introduced step by step in the participating organisations, and this may have led to a more protracted adoption process or implementation fatigue; influencing professional views. However, we believe our data presents a pragmatic picture of the implementation process, which can be useful to services intending to implement PCOMs.

Future research

We described the importance of using PCOM data to make clinical decisions and demonstrate the impact of palliative care. However, we need more research to develop acceptable ways to interpret and use data from PCOMs with patients whose health is deteriorating.

It is important to conceptualize and measure implementation outcomes to determine the effectiveness of implementation strategies (32). Although our study addresses important implementation outcomes, we need more quantitative research to measure these outcomes systematically.

Conclusions

We identified key considerations and recommendations for PCOM implementation in specialist palliative care settings. All CFIR domains need consideration for effective implementation.

We need to recognise that patients, families and professionals may have differing views about the advantages and disadvantages of using outcome measures, particularly in relation to feelings of reassurance and burden. Using the information from PCOMs was very important to patients, family caregivers and health professionals. Any implementation of PCOMs in specialist palliative care must make sure the information from PCOMs is regularly fed back to clinicians and services, and used to improve care for patients and families. This can be facilitated by embedding PCOMs in daily clinical interactions and providing adequate time and resource to analyse and use data from PCOMs.

Acknowledgements

We would also like to thank Cathy Shipman who contributed to the coding and analysis of the interviews.

Funding: This paper presents independent research part funded by Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity, and part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (RP-PG-1210-12015-C-CHANGE: delivering high quality and cost-effective care across the range of complexity for those with advanced conditions in the last year of life). The research was also supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: IPOS (used in the OACC suite of outcome measures) was developed at the Cicely Saunders Institute, where this research study was conducted. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the UK National Research Ethics Service (No. 14/LO/1669) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- Health Do. High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. The Stationery Office, 2008.

- Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:714-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Etkind SN, Daveson BA, Kwok W, et al. Capture, transfer, and feedback of patient-centered outcomes data in palliative care populations: does it make a difference? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:611-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- (PCOC) PCOC. Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration: Three years of progress (2010 to 2013). Wollongong: Australian Health Services Research Institute, University of Wollongong, 2013.

- Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Outcome measures in palliative care for advanced cancer patients: a review. J Public Health Med 1997;19:193-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Development and validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care: the palliative care outcome scale. Palliative Care Core Audit Project Advisory Group. Qual Health Care 1999;8:219-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collins ES, Witt J, Bausewein C, et al. A Systematic Review of the Use of the Palliative Care Outcome Scale and the Support Team Assessment Schedule in Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:842-53.e19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bausewein C, Daveson BA, Currow DC, et al. EAPC White Paper on outcome measurement in palliative care: Improving practice, attaining outcomes and delivering quality services-Recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Task Force on Outcome Measurement. Palliat Med 2016;30:6-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antunes B, Harding R, Higginson IJ. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliat Med 2014;28:158-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dunckley M, Aspinal F, Addington-Hall JM, et al. A research study to identify facilitators and barriers to outcome measure implementation. Int J Palliat Nurs 2005;11:218-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bausewein C, Simon ST, Benalia H, et al. Implementing patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in palliative care-users' cry for help. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Witt J, de Wolf-Linder S, Dawkins M, et al. Introducing the Outcome Assessment and Complexity Collaborative (OACC) Suite of Measures-A Brief Introduction. Version 2. King’s College London, 2014.

- Masso M, Allingham SF, Banfield M, et al. Palliative Care Phase: Inter-rater reliability and acceptability in a national study. Palliat Med 2015;29:22-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mather H, Guo P, Firth A, et al. Phase of Illness in palliative care: Cross-sectional analysis of clinical data from community, hospital and hospice patients. Palliat Med 2018;32:404-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abernethy AP, Shelby-James T, Fazekas BS, et al. The Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) scale: a revised scale for contemporary palliative care clinical practice BMC Palliat Care 2005;4:7. [ISRCTN81117481]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Addington-Hall J, Hunt K, Rowsell A, et al. Development and initial validation of a new outcome measure for hospice and palliative care: the St Christopher's Index of Patient Priorities (SKIPP). BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:175-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Gao W, Jackson D, et al. Short-form Zarit Caregiver Burden Interviews were valid in advanced conditions. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:535-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kutner JS, Bryant LL, Beaty BL, et al. Symptom Distress and Quality-of-Life Assessment at the End of Life: The Role of Proxy Response. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;32:300-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horton R. Differences in assessment of symptoms and quality of life between patients with advanced cancer and their specialist palliative care nurses in a home care setting. Palliat Med 2002;16:488-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pautex S, Berger A, Chatelain C, et al. Symptom assessment in elderly cancer patients receiving palliative care. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2003;47:281-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: The qualitative researcher’s companion. 2002.

- NatCen. The Framework approach to qualitative data analysis. Available online: https://www.surrey.ac.uk/sociology/research/researchcentres/caqdas/files/Session%201%20Introduction%20to%20Framework.pdf. 2012.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res 2008;17:179-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh J, Long AF, Flynn R. The use of patient reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice: lack of impact or lack of theory? Soc Sci Med 2005;60:833-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boyce MB, Browne JP, Greenhalgh J. The experiences of professionals with using information from patient-reported outcome measures to improve the quality of healthcare: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:508-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stukenborg GJ, Blackhall LJ, Harrison JH, et al. Longitudinal patterns of cancer patient reported outcomes in end of life care predict survival. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:2217-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marshall S, Haywood K, Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract 2006;12:559-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:211. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]