Radiation oncology resident education in palliative care

Introduction: rationale for palliative care education in radiation oncology

Palliative care provides an approach focusing on quality of life through relief of distressing symptoms and integration of psychological and spiritual aspects of medical care (1). Expert panels have concluded that patients with advanced cancer should receive early dedicated palliative care services concurrently with active treatment as studies show the integration of palliative care has the potential to improve quality of life, decrease health care costs, and improve survival (2,3). In response to this, ASCO published national guidelines regarding the early integration of palliative care in oncology. Patients with advanced cancer, whether inpatient or outpatient should receive dedicated palliative care services, early in their disease course, concurrent with their active treatment (4). Although the beneficial effects of palliative care are recognized, available specialty palliative care services are insufficient to meet the palliative care needs of the growing volume of patients with serious illnesses (5). Therefore, there is recognition of the need to promote generalist palliative care competencies among non-specialists, together with advocating for growing the infrastructure of specialty palliative care services (6).

As part of the planned and continued expansion of palliative care, a coordinated effort has been proposed distinguishing primary palliative and specialist palliative care to co-exist and support each other (7). In this model primary palliative care encompasses skills that all treating physicians, should have that includes basic management of pain, symptoms, depression, anxiety, and discussions about prognosis, goals of treatment, suffering, and code status. The specialty palliative care in this model encompasses management of more complex cases such as refractory pain, depression, and assistance for goals of care or futility. Radiation oncologists in this model would be responsible for primary palliative care to ensure increased patient access to palliative care and delivery of this care earlier for patients. So by incorporating basic palliative care services early on by the treating team and the support from the specialist team, the patient reaps the benefits.

Radiation Oncologists have potential to deliver primary palliative care through consultation, delivery of radiation and weekly management of symptoms related to therapy, making referrals to supportive services, and continued follow-up. It is estimated that approximately one third of all consultations are for palliative intent radiation therapy, and around one half of treatments are with palliative intent in localized or disseminated disease (8,9). When delivering palliative radiation therapy 82% of consultations are likely to require multiple domains including physical symptoms, care coordination, goals of care, and psychosocial issues (9). Additionally, during this course patients may frequently experience depression and anxiety and require supportive care to their symptoms (10).

Radiation oncology physicians encounter a high volume palliative care issues in consultations with a potential role for delivering advanced palliative care With the increased demand of these services, education of radiation oncologists in training is the starting point for expanding further integration into clinical practice. This review article serves to assess the available literature published on palliative care education in radiation oncology residencies in the United States.

Radiation oncology program director perspectives on palliative care education

Although more than half of radiation oncology programs provide educational activities for radiation oncology trainees the content is not comprehensive. Wei et al. aimed to assess the state of palliative care educational curriculum in residency programs in the United States by surveying 57 program directors of radiation oncology programs (11). There was strong perception that palliative supportive care (93%) and radiation oncology (93%) were important competencies, however only 67% of programs had formal educational activities. Most of the programs had one or more hours of didactics managing pain, neuropathic pain, nausea and vomiting, but few had dedicated lectures on initial management of fatigue, spirituality, and advanced care directives. Most of the education on palliative radiation was dedicated to brain, bone, and spine but less likely in visceral or skin metastasis. The results from the programs surveyed show the disparity as one third of the radiation oncology programs do not have integrated didactics. Additionally, the programs that do have structured curricula are deficient in non-treatment related symptom management. The survey was limited in that it examined the perspective of only the program directors, but also highlights the opportunity that exists to provide formal palliative radiation education for their residents

Radiation oncology resident perspectives on palliative care education

The resident perspective was evaluated by Krishnan et al. at Dana-Farber and revealed that the amount of time dedicated to palliative education in the programs that provide the curriculum is minimal (12). The survey was completed by 404 US radiation oncology residents developed by an expert panel. It examined domains including pain management, symptom management, psychosocial care, cultural care, spiritual care, care coordination, legal issues, communication/goals of care, and advanced care planning. Residents rated the adequacy of their training in each domain. Receiving 5 or more hours of dedicated training was a predictive of higher confidence score on all domains, however 75% of residents reported having less than 5 hours of dedicated training. On average 79% of residents felt that their palliative care training as not at all or minimally adequate despite the 96% that viewed as an important competency for residents.

This evaluation of the residents perspective was the first to show that residents almost unanimously felt their training to be inadequate and had less than five hours of dedicated time. Even though two thirds of programs have reported having formal educational activities, most of their dedicated training was minimal. The limitation of the study is that it did not assess the quality of the educational means, but it did show that more time exposed to dedicated training may translate to more confidence. The results of the survey may influence programs to potentially increase the quantity of dedicated palliative care directed time for residents.

Beyond formal didactics, radiation oncology residency training appears to be a formative opportunity to shape how physicians approach radiation near the end of life (13). Lloyd et al. aimed to document the use of radiation treatment near the patient’s end of life through an anonymous survey examining clinical and psychosocial factors, as well as intentions to deliver palliative radiation treatments. Out of the 139 responses, 47% were completed by radiation oncology residents. Factors deemed important to radiotherapy at the end of life included patient preference, treatment tolerance, and palliative intent. Residents were more likely than attendings to list the influence of mentors and peers shaping their practice and attitudes about radiation near the end of life These findings show that residents place value in the clinical experience of the faculty in addition to formal curriculum and guidelines. This information could be applied to the development of an educational intervention that includes a faculty lead clinical component to training the residents.

Palliative care educational interventions in radiation oncology

An advanced communication centered intervention was piloted by Bylund et al. at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The program was made up of nine teaching modules including didactic and experiential group work (14). This was done from 2006–2010 for a total of 515 participants, of which 323 were oncology attendings, nurses, or trainees. The course utilized small group role play sessions as a core component of training, devoting at least half of every 3-hour training module to these role play sessions. During these sessions, learners received feedback from their facilitator and others in their small group in addition to watching instant video playback of their interaction with the simulated patient. They were administered a pre- and post-test with improvement of self-efficacy scores in breaking bad news, shared decision making, response to difficult patients, discussing prognosis, the transition from curative to palliative care, death and dying, and responding to adverse events.

This study shows that the implementation of an advanced communication skills training program is feasible and has a significant impact on participant’s self-efficacy. The significance of this intervention that there was a clear improvement in trainee’s knowledge and confidence in communication skills. Because the course is more comprehensive there may be limitation in the widespread applicability among residency programs. Programs could possibly modify the intervention to less than nine sessions focusing on high yield material specifically tailored to radiation oncology residents.

A didactic curriculum was developed by Garcia et al. at University of California San Francisco and was implemented in their radiation oncology residency program. The course consisted of daily 1-hour didactics based on American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine palliative care domains (15). Pre- and post-course feedback surveys were conducted to assess the newly developed curriculum and find areas of improvement for future didactics. After the course residents reported improved scores in management of uncontrolled pain, discussing the purpose of palliative treatments, and discussing the role of palliative care providers. There was also statistically significant improvements in leading a family meeting, assessing effectiveness of analgesics, defining control of pain, intervening for uncontrolled pain, management of opioid and non-opioid analgesics, screening and treating for mood symptoms, and discussing the purpose and role of palliative care treatments and providers.

The significance of this curriculum is that it was developed specifically for radiation oncology residents and showed that a one week course had the ability to improve management of multiple palliative care domains for their trainees. The course was limited in that it only had five hours total of didactics and did not integrate any clinical application of the lectures. This type of didactic teaching may be applicable to most residency programs without much requirement away from clinic or already scheduled didactic time, and the format could possibly be distributed for other programs to integrate and educate their residents. This type of didactic teaching may be the first step toward multi-institutional collaboration to aid in the development of palliative education in radiation oncology residency.

With the lack of structured development and evaluation of communication skills in radiation oncology residency programs, a novel standardized patient-based curriculum was developed by Ju et al. at University of Pennsylvania (16). The authors assessed 11 radiation oncology residents’ postgraduate years 2–5 paired with six faculty. The residents were challenged to give the delivery of bad news to patients in two scenarios with standardized patients. This included two 1-hour session with a 45-minute summary session scored by standardized patients, the observing faculty, and the trainee. The evaluation metric used specifically examined physician-patient communication. Overall resident performance was good to excellent; however, residents were more likely to have a critical self-assessment with greater need for improvement compared to standardized patient and faculty evaluation of performance. Residents and faculty gave positive reviews of the program and was regarded as a valuable educational experience. The authors concluded that perceived lack of empathy, absence of shared decision making, and excessive medical jargon were barriers to developing strong interpersonal relationships with patients.

This intervention may create opportunity for residents to apply their didactic obtained knowledge to the clinical setting to overcome barriers hindering their confidence in discussing issues with patients. The limitations of the program are that it potentially requires more resources with which may not be widely accessible. Programs may consider using this as a supplement to didactic or communication-based interventions for their residents.

Integration of palliative care clinical rotations in radiation oncology

A dedicated palliative radiation oncology service was developed by Tseng et al. at Dana-Farber which aimed to cater to the ASCO recommendation of tailoring palliative cancer care to advanced cancer patients (17). The palliative care radiation oncology service composed of a rotating attending physician, resident, nurse practitioner, nurse, and dedicated administrative staff with daily rounds. The authors assessed the quality and perceptions of palliative care delivery among physicians practicing. Using an online survey, perceptions of delivered care was compared between clinic practices with and without a dedicated palliative care radiation oncology service. The survey evaluated 10 measures completed by 102 radiation oncology providers, that included 28 residents with option for free text feedback. Residents rotating through the service perceived that the program improved communication with patients and families, staff experience, time spent on technical aspects, appropriateness of treatment recommendations, dose fractionation scheme, and patient follow-up.

In the free text feedback section there were two distinct themes including that the service improved quality of patient care, resident education, and improved staff experience. The second theme was that there was need for improved patient care, standardized aspects of clinical care, ensuring a resident responsibility solely with the palliative care service, and consideration of dedicated palliative care service attendings. Compared with the physicians in departments without a dedicated palliative service, physicians with a dedicated palliative care service were more likely to rate the quality of their department’s palliative care more highly and this was statistically significant.

The authors demonstrate that a dedicated palliative radiation oncology service significantly improved the participant’s perception of palliative care delivered in many domains. The applicability to other programs may be limited as it requires a larger volume center that has the faculty support to create a dedicated service. The study shows that a service is feasible and comprehensive option and is a promising means to fill the current void in palliative care resident education.

Palliative care educational modules for oncology trainees

Education in core palliative care skills in oncology has been reported to be lagging in medical, gynecology, surgical, pediatric and radiation oncology (18-21). High quality cancer care requires oncology professional to be proficient in basic palliative care. The increased evidence of lack of formal palliative care training has caused health organization to start investing in the palliative care training in their oncology residencies. Additionally, companies have developed resources that are online based for oncology practices with real time feedback including programs such as Vital Talk, Ariadne Lab’s Serious Illness Care Program, and Center to Advance Palliative Care (22).

At Memorial Sloan Kettering oncology fellows, residents, and nurses are required to take a standardized modular curriculum focusing on communication skills. Moffitt Cancer Center provides half-day module-based workshops as well as pain and symptoms management lectures that are mandatory for fellows and open to residents (23). The half day workshops include Vital Talk; a signature online communication course available for purchase with cognitive mapping and real time feedback showing improved communication skills within their organization. MD Anderson Cancer Center has adopted a monthly one-hour seminars in the form of a communication skills trainings (CST) course for first year medical oncology fellows structured to overcome the time constraint from busy clinical schedules (24). The early adopting programs are demonstrating that the early integration of palliative care and online based modules can be transformative, sustainable, and affordable to most programs. The integration of palliative care strategy in the early adopting programs is could serve as a guide for increasing the exposure and education for radiation oncology residents.

Continuing education through fellowship in palliative care

Another important mechanism by which radiation oncologists can enhance their training and broaden their knowledge in palliative care is in through the Hospice and Palliative Fellowship available for ABR candidates (25). The one year fellowship emphasizes strategies to improve the care of patients with chronic illness and those near end of life and is offered at many institutions across the United States. The advantages of providing residents with opportunity for extensive clinical experience, comprehensive didactics, and one to one mentoring over one year of dedicated time. This extensive training may provide ability to foster leaders in the field of palliative radiation oncology and provide guidance and structure for the continued integration of palliative education in residency programs.

Discussion

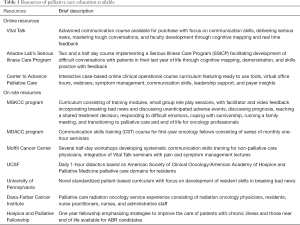

While resources for palliative care education exist through formal didactics and curriculums, role-playing sessions, and real-life exposure through dedicated palliative care services, there remains an unmet need for widespread and standardized adoption of palliative care education within radiation oncology resident training (Table 1).

Full table

The future of palliative care education in radiation oncology is developing with pioneering strategies to enhance resident education. Programs may strive to improve the quality and quantity of didactics with clinical exposure to standardized patients, increase the use of teleconference, online modules, and palliative care journal clubs. In addition, the residents may choose to pursue the palliative care fellowship with potential to contribute to the further development of palliative care in radiation oncology. Finally, the emphasis on palliative care topics on the board examinations would provide incentive for programs to provide the resources and residents to study the material and translate the knowledge to clinical practice.

The surveys of radiation oncology programs and residents highlight the perceived importance of palliative care yet there is lack of structured curriculum dedicated to resident palliative care education. Meanwhile some academic centers are piloting interventions expanding communication skills, didactics, and the integration of a dedicated palliative care service show benefit to resident education. Future opportunities for palliative care education in radiation oncology training include shared formal standardized didactics via teleconference or webinar, integration or joint programs through a dedicated palliative care service, emphasis of palliative care topics on the radiation oncology board examinations, and palliative care fellowships.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. World Health Organization, 28 Jan. 2012

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96-112. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update Summary. J Oncol Pract 2017;13:119-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, et al. Future of the Palliative Care Workforce: Preview to an Impending Crisis. Am J Med 2017;130:113-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schenker Y, Arnold R. The next era of palliative care. JAMA 2015;314:1565-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaffray DA. Radiation Therapy for Cancer. Cancer: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 3), U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Nov. 2015

- Parker GM, LeBaron VT, Krishnan M, et al. Burden of palliative care issues encountered by radiation oncologists caring for patients with advanced cancer. Pract Radiat Oncol 2017;7:e517-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frick E, Tyroller M, Panzer M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life of cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy: A cross-sectional study in a community hospital outpatient centre. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007;16:130-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei RL, Colbert LE, Jones J, et al. Palliative care and palliative radiation therapy education in radiation oncology: A survey of US radiation oncology program directors. Pract Radiat Oncol 2017;7:234-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krishnan M, Racsa M, Jones J, et al. Radiation oncology resident palliative education. Pract Radiat Oncol 2017;7:e439-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lloyd S, Dosoretz AP, Yu JB, et al. Academic and Resident Radiation Oncologists' Attitudes and Intentions Regarding Radiation Therapy near the End of Life. Am J Clin Oncol 2016;39:85-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bylund CL, Brown RF, Bialer PA, et al. Developing and implementing an advanced communication training program in oncology at a comprehensive cancer center. J Cancer Educ 2011;26:604-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garcia MA, Braunstein SE, Anderson WG. Palliative Care Didactic Course for Radiation Oncology Residents. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017;97:884-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ju M, Berman AT, Hwang WT, et al. Assessing interpersonal and communication skills in radiation oncology residents: A pilot standardized patient program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;88:1129-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tseng YD, Krishnan MS, Jones JA, et al. Supportive and palliative radiation oncology service: Impact of a dedicated service on palliative cancer care. Pract Radiat Oncol 2014;4:247-253. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ross MK, Doshi A, Carrasca L, et al. Interactive Palliative and End-of-Life Care Modules for Pediatric Residents. Int J Pediatr 2017;2017:7568091. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roth M, Wang D, Kim M, et al. An assessment of the current state of palliative care education in pediatric hematology/oncology fellowship training. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;53:647-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eskander RN, Osann K, Dickson E, et al. Assessment of palliative care training in gynecologic oncology: a gynecologic oncology fellow research network study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:379-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larrieux G, Wachi BI, Miura JT, et al. Palliative care training in surgical oncology and hepatobiliary fellowships: a national survey of program directors. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22 Suppl 3:S1181-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Equipping Oncology Professionals with Core Palliative Care Skills. Available online: https://palliativeinpractice.org/palliative-pulse/palliative-pulse-august-2017/equipping-oncology-professionals-palliative-care-skills/#_edn13

- Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banieree SC, et al. Communication Skills Training for Oncology Professionals. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1242-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epner DE, Baile WF. Difficult conversations: teaching medical oncology trainees communication skills one hour at a time. Acad Med 2014;89:578-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Subspecialties for Diagnostic Radiology: The American Board of Radiology, 2018, Available online: www.theabr.org/diagnostic-radiology/subspecialties/hospice-palliative-medicine/requirements