Communication skill frameworks: applications in radiation oncology

Introduction

Skillful communication is essential in the delivery of high-quality, patient-centered cancer care. In addition to strengthening the patient-physician relationship and promoting a model of informed and shared decision-making, patient-centered communication is associated with improved health-related quality of life, mood, symptom control, adherence to therapeutic treatments, and overall satisfaction (1-7). Effective communication also benefits providers, facilitating increased resilience and a greater sense of personal accomplishment (1).

Despite the growing appreciation for the critical role of skilled communication in oncology, breakdowns in communication are common (8-9). Cancer patients may leave oncology visits with confusion regarding the plan of care and treatment options; inaccurate or incomplete prognostic awareness; and unaddressed emotional, psychological, and physical concerns (10-12). Further, most of the efforts to address the need for communication skill training in oncology have been limited to the field of medical oncology with significantly less emphasis placed on developing communication skills among surgical or radiation oncologists.

A rationale for formal communication skills training in radiation oncology

A large proportion of patients referred to radiation oncology are treated with palliative intent (13). As such, radiation oncologists regularly have opportunities to participate in various complex communication tasks associated with an advanced cancer diagnosis, detailed in Table 1.

Full table

Since formal communication training has not been a consistent part of radiation oncology training programs, the majority of radiation oncologists in practice today have not received education specifically focused in this area. For this and other reasons, radiation oncologists may be less likely to engage patients and family members in challenging patient-centered conversations around prognosis (14-16). In a study by Keating et al., radiation oncologists were the least likely of all oncology specialists to discuss prognosis with their advanced cancer patients (17). Similarly, in a study comparing communication during initial oncology consultation visits, compared to medical oncologists, radiation oncologists were less likely to discuss prognosis, to initiate a social exchange, or to ask patients open-ended questions (3). Radiation oncologists spent a greater percentage of the visit interrupting and their communication style was rated as less patient-centered, more hurried, and less clear. In addition, radiation oncologists spent an average of 9 seconds checking patient understanding and 25 seconds building rapport (partnership building and active support) during initial consultation (3).

Radiation oncologists, however, are uniquely positioned to engage patients and families in discussions regarding prognosis, advance care planning, treatment preferences, and goals of end of life care. Evidence suggests that prognostic accuracy decreases with increased duration of the patient-physician relationship (18). Radiation oncologists can often provide a “fresh perspective” in evaluating a patient’s prognosis, especially when patients are receiving daily treatments, and thus may bring to light a greater sense of urgency regarding advance care planning and end-of-life talks. Further, studies indicate that cancer patients may actually prefer to discuss advance care planning with physicians who can function as “disinterested parties” due to fears of upsetting their medical oncologist with whom they may have had the longest relationship (19,20).

The structure of radiation oncology clinic also lends itself to these common yet complex communication tasks. Patients on treatment are seen at least weekly, which allows for sequential and frequent visits that facilitate the forward progression of these conversations. Topics for discussion such as prognosis and end of life planning are especially likely to evolve over multiple discussions, as patients and families are able to process information and emotional reactions over time. In particular, the possibility of hospice care may be initially introduced in a general way at a consultation visit with more detailed information provided during on-treatment visits. Patients may also choose to bring in family members at these later visits to partner in information-sharing and decision-making.

Basic frameworks for communication skills training

Communication frameworks serve as roadmaps that anchor and guide clinicians through challenging conversations. They offer a systematic, teachable, skill-driven approach to moving discussions forward while eliciting patients’ priorities, goals, and values and formulating patient-centered management decisions (20,21). Several approaches to communication frameworks exist, although those developed by VitalTalk and the Serious Illness Care Program are thought to be the most accessible and effective. Both have been well-studied and are in operation internationally.

VitalTalk was formed by several U.S.-based palliative care physicians in 2012. Initially funded by the National Institutes of Health, VitalTalk is now a 501c3 nonprofit organization whose purpose is to disseminate communication research into clinical practice (22).

The Serious Illness Conversation Guide is a set of structured questions designed from best practices in generalist-level palliative care. It serves as a framework for clinicians to explore what is most important to patients and their families. “The Guide” (available online: https://www.ariadnelabs.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/08/Serious-Illness-Conversation-Guide-5.22.15.pdf) is one element of a larger six-part program called the Serious Illness Care Program developed at Ariadne Labs in Boston, MA, USA that functions at a systems level to provide support for clinicians carrying out important conversations with patients and caregivers/family members (23).

Fundamental communication skills

Recognizing and responding to emotion

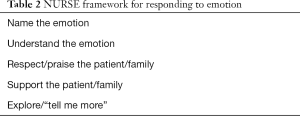

Recognizing expressions of emotion and responding with empathy are fundamental communication skills. They can facilitate further disclosure and have been shown to result in improved patient understanding of illness and quality of life outcomes (24,25). A cancer diagnosis is often accompanied by emotional distress, which can directly interfere with a patient’s ability to process medical information and cope with his or her illness (26,27). The NURSE framework (Table 2) is an established way of conceptualizing various types of empathic statements (28).

Full table

Anxiety, anger, guilt, panic, vulnerability, isolation, depression, frustration, hopelessness, fear, and other strong negative emotions are commonly present at the time of an initial cancer diagnosis and may occur throughout the disease course, especially at times of disease progression or complications from either the disease or its treatments (29-31). These emotional reactions can range from normal adjustment reactions to disabling disorders requiring medical treatment. At any level of severity, this emotional noise has a significant impact on an individual’s ability to understand or process medical information and must be addressed before moving forward in the conversation.

Cancer patients may also feel reluctant to disclose their emotional distress to their providers due to fear of being burdensome, judged, or even being denied treatment (32-37). A patient’s emotional state, however is often communicated through the use of indirect verbal and non-verbal cues (38-41). For example, “I keep wondering if the cancer has spread” may actually be an expression of pervasive anxiety or guilt for having not sought medical evaluation or treatments earlier. Indirect cues offer an opportunity for providers to offer emotional support without lending false hope (42-44).

Common pitfall responses to indirect cues include avoidance and redirection (41-43). In the above example, a radiation oncologist might instinctively provide additional medical information, instead of attending to the question’s emotional origin (e.g., anxiety) first. An immediate cognitive response is “there is no evidence of metastatic disease on your recent staging CT.” This type of “terminator statement” does not acknowledge the underlying anxiety which may have prompted the patient’s statement. A response to the question’s emotional underpinning, on the other hand, may instead be, “I can’t imagine how terrifying it must be to think about this” (41,44). This is an example of an “understand” statement from NURSE. A response to the question’s emotional origin (I) assures that the patient feels heard and (II) allows the patient to respond in a way that provides important data to the provider regarding whether it is necessary to continue addressing the patient’s underlying emotion or whether it is okay to move on (45-48). Empathic responses have been also associated with increased patient satisfaction, quality of life, treatment adherence, mood, coping ability, and stronger patient-provider alliance (42,49-51).

Case 1

Jerry is a 52-year-old man with diffusely metastatic prostate cancer who presents to radiation oncology clinic for an initial consultation. He has severe, progressive right hip pain with evidence of a new bone metastasis in his proximal right femur. While eliciting Jerry’s understanding of his illness, the radiation oncologist notices that Jerry becomes tense and leans away. In a loud voice, he interrupts: “just treat my pain, already! I can barely walk. I can’t sleep. Enough with the questions!”

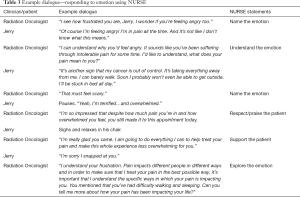

The radiation oncologist notices and responds to verbal and non-verbal cues of Jerry’s distress (Table 3). By attending to Jerry’s frustration, she allows him space to defuse his emotions and feel heard. Once she validates that his emotional responses are entirely normal and expected, Jerry calms down and she is able to continue investigating his pain (28).

Full table

Delivering serious news

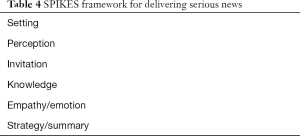

Delivering serious news is one of the most challenging communication tasks in medicine. A patient’s experience during this type of encounter is critically important and should be considered at all times. SPIKES (Table 4) is a roadmap that outlines the key parts of a conversation involving serious news delivery (28). Information should be provided in a private, quiet setting whenever possible and with limited interruptions or distractions. Sitting down for this process is an important non-verbal signal of presence and respect for the patient and conversation. It may be helpful to have key team members available (e.g., nurse or social worker) to jump into the conversation at appropriate points.

Full table

Prior to disclosing serious news, radiation oncologists should assess patients’ understanding of the clinical situation and the type of information they want to know. It is important that assumptions are not made regarding patients’ understanding or desired extent of disclosure. Radiation oncologists should specifically ask patients for permission prior to sharing the new information and adhere to patients’ expressed communication preferences. A “warning shot” or verbal statement preparing a patient for the news about to be delivered can be an effective tool when there is concern that the news will come as a surprise.

Next, radiation oncologists should state the news clearly and concisely. Often a single, unequivocal statement is sufficient. Attention should be made to avoid medical jargon and to pause while patients process the information. Radiation oncologists should be sure to assess patients’ understanding of what was communicated and to be attentive to verbal and non-verbal expressions of emotion (e.g., “How is this information sitting with you?”). Patients may respond with varying degrees and types of emotion, including relief, dread, anger, or acceptance. Radiation oncologist should provide empathetic support of any emotion expressed, to ensure that patients feel supported. It is critical that they have time to process information and evaluate their feelings prior to trying to make any further decisions about treatment. It is also critical to make sure that patients do not feel abandoned. If the plan is unlikely to include additional follow-up visits with the radiation oncologist, a statement should be made to explain that the patient is welcome to schedule additional visits with the radiation oncologist if desired. Patients may want to meet with their established practitioners again, if only to ensure that the relationship is maintained. An example dialogue for delivering serious news is shown in Table 5.

Full table

Case 2

Dana is a 49-year-old woman diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma of the right breast found to have invasion of the chest wall on radical mastectomy who presents to radiation oncology clinic for post-mastectomy irradiation. The referral was initially placed after her mastectomy 3 months ago, but due to changes in her employment with a temporary lack of insurance coverage, she has had delayed follow-up. In anticipation of this visit, her medical oncologist ordered CT chest/abdomen/pelvis for re-staging, performed yesterday. She has not yet been informed of the results. Upon reviewing her imaging, the radiation oncologist notes progression of disease with multiple hepatic and pulmonary lesions.

Discussing prognosis

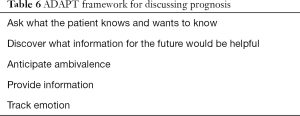

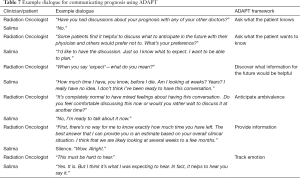

The majority of cancer patients prefer to have a clear understanding of their illness and expected disease trajectory yet the extent to which these conversations are carried out in a way that facilitates understanding is variable (51-55). The ADAPT framework for communicating prognosis is described in Table 6 (28).

Full table

Conversations regarding prognosis are frequently deferred until very late in the disease trajectory when there may be insufficient time to align end of life care with a patients’ preferences (56). Oncologists may communicate an overly optimistic prognosis for several reasons, including the worry that sharing information about a poor prognosis may result in loss of hope (56). The prevalence of prognostic non-disclosure was highlighted in a study of over 1,000 patients by Weeks et al. in which 69% of patients with metastatic lung cancer and 81% of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer were unaware that chemotherapy was not at all likely to cure their disease (57). Similarly, 64% of the lung cancer patients treated with radiotherapy in this patient population lacked understanding that radiotherapy was not at all likely to be curative (58).

It is important for radiation oncologists to gauge patients’ prognostic awareness and desire for information regarding anticipated disease trajectory and life expectancy, This is especially true when further radiation treatment may involve acute toxicities or when trade-offs regarding symptom burden may deserve special consideration. A conversation with the referring provider about a patient’s prognosis may be warranted to ensure that all providers are on the same page and present the same information to the patient. Radiation oncologists should be prepared with responses for patients who express ambivalence about discussing their prognosis. This should be thoughtfully explored. Efforts to understand the type of prognostic information that would be most helpful and underlying concerns that might accompany this type of information should be made. For instance, some patients may desire detailed, numerical information while others may ask about whether they will be able to attend specific, important future events. It is essential for the radiation oncologist to be able to provide honest prognostic estimates and to avoid the tendency toward unrealistic optimism. Prognostic estimates are often best described in terms of a time interval, for example hours to days, days to weeks, or weeks to months. Uncertainty in prognostication should be acknowledged. Framing uncertainty in terms of best case/worst case scenarios can be helpful. Underlying the prognosis discussion, paying attention to patients’ emotional reactions and responding with statements of empathy (Table 2) is key. An example dialogue for discussing prognosis is shown in Table 7.

Full table

Case 3

Salima is a 62-year-old woman with metastatic esophageal cancer who is referred to radiation oncology for palliative management of progressive dysphagia.

Discussing goals of care

Identifying patients’ goals, hopes, worries, values, beliefs, priorities, and preferences is essential to the process of shared decision-making. When possible, these conversations should precede discussions about specific medical interventions and treatment options so that the latter can be framed in an appropriate context and expectations can correlate with anticipated outcomes. Frequently, a patient will have several concurrent goals—such as prolonging life and minimizing suffering—and these goals may at times conflict. Given the dynamic nature of a patient’s priorities and preferences, goals of care may need to be, and should be, revisited and revised at multiple points throughout the course of illness. If a patient’s goals are not realistically achievable, a radiation oncologist can assist the patient in reframing goals such that hope is maintained and achievable goals are identified.

As yet, data suggest cancer patients’ goals of care are not consistently addressed within the context of their values and preferences. In a study by Mack et al., only 27% of nearly 1,500 patients who died from stage IV colorectal or lung cancer had end of life goals of care discussions documented by their oncologists (59). Failure to engage patients and families in discussions about end of life care may result in unreasonable expectations and/or interventions that do not result in treatment benefits. These may also lead to increased caregiver stress during the bereavement period (51,59-65).

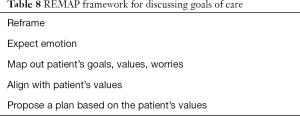

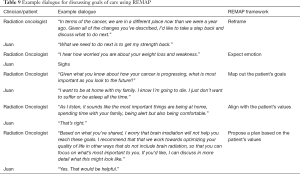

An ideal conversation about goals of care is one that (I) begins with an ascertainment of patient’s or family’s illness understanding; (II) involves sharing of knowledge regarding pertinent clinical findings and results; (III) allows for time to process emotion and responses of empathy; (IV) elicits values, worries, and priorities from patients and family members given new and potentially distressing information; (V) summarizes information shared to reassure the patient and family members that they were heard; and finally (VI) offers a recommendation about treatment couched in empathy and with the communicated priorities in mind. In this way, these conservations should be less treatment-centric and more patient values-centric. An established communication framework for discussing goals of care, REMAP, is described in Table 8 (66). An example dialogue for discussing goals of care is shown in Table 9.

Full table

Full table

Case 4

Juan is a 68-year-old man with stage IV lung cancer. He was recently found to have diffuse brain metastases and was referred to radiation oncology for possible whole brain radiation. You had previously treated him with palliative radiotherapy for a painful bone metastasis approximately 1 year ago. At that time his functional status was excellent and his expressed goal was “to beat this cancer and resume life as usual.”

Today he is frail and lethargic with a recent unintentional 15-lb weight loss. He reports spending the majority of time in bed. He has minimal appetite and needs assistance in nearly all activities of daily living. He expresses concern about his progressive weight loss but he is hopeful that brain irradiation will improve his appetite and energy level so that he can “get strong again.”

Bottom line

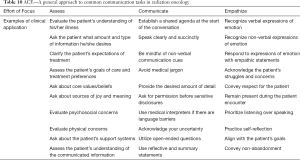

In the broadest sense, skilled communication stems from the ability to listen actively, to speak with intention, and to attend to patients’ and/or family members’ emotions throughout the process. Communication skills can be effectively learned through the use of discrete frameworks, some of which are described above. These frameworks are meant to serve as cognitive aids, not as conversation outlines or checklists. When first developing these skills, however, it is not uncommon for early learners to get stuck when trying to apply specific frameworks to various challenging conversations. In those instances, some may prefer a simplified approach involving three focused efforts: assessing; communicating; and empathizing (Table 10).

Full table

Conclusions

Skilled communication facilitates alignment of treatments with patients’ goals and values and is essential to the delivery of high quality cancer care. Emotional reactions to medical information can pose a barrier to a patient’s illness understanding. Skilled responses to emotional reactions assure patients they were heard and facilitate purposeful progression of difficult conversations. As yet, the majority of radiation oncologists lack formal training in this area. Given that evidence affirms that empathic, patient-centered communication improves patient understanding, the patient-provider alliance, quality of life, and the overall quality of cancer care (67) communication skills should be prioritized as a core competency within radiation oncology.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:755-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epstein RM, Hadee T, Carroll J, et al. "Could this be something serious?"; Reassurance, uncertainty, and empathy in response to patients’ expressions of worry. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1731-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dimoska A, Butow PN, Dent E, et al. An examination of the initial cancer consultation of medical and radiation oncologists using the Cancode interaction analysis system. Br J Cancer 2008;98:1508-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vogel BA, Leonhart R, Helmes AW. Communication matters: The impact of communication and participation in decision making on breast cancer patients’ depression and quality of life. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:391-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Girgis A, Cockburn J, Butow P, et al. Improving patient emotional functioning and psychological morbidity: evaluation of a consultation skills training program for oncologists. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:456-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gattellari M, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. Sharing decisions in cancer care. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:1865-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown J. How clinical communication has become a core part of medical education in the UK. Med Educ 2008;42:271-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, et al. Toward patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1784-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prouty CD, Mazor KM, Greene SM, et al. Providers’ perceptions of communication breakdowns in cancer care. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1122-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Daugherty CK, Hlubocky FJ. What are terminally ill cancer patients told about their expected deaths? A study of cancer physicians’ self-reports of prognosis disclosure. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5988-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, et al. The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Cancer 2000;88:226-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al. Effect of a patient-centered communication intervention on oncologist-patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:92-100. [PubMed]

- Murphy JD, Nelson LM, Chang DT, et al. Patterns of care in palliative radiotherapy: a population-based study. J Oncol Pract 2013;9:e220-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Das LC, Son CH, Daily EW, et al. The role of the radiation oncologist in goals-of-care discussions. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:42. [Crossref]

- Ellsworth S, Smith T, Lutz S. Radiation oncologists, mortality, and treatment choices. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013;87:437-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei RL, Mattes MD, Yu J, et al. Attitudes of radiation oncologists toward palliative and supportive care in the United States: report on national membership survey by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). Pract Radiat Oncol 2017;7:113-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer 2010;116:998-1006. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2000;320:469-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lamont EB, Siegler M. Paradoxes in cancer patients’ advance care planning. J Palliat Med 2000;3:27-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banerjee SC, et al. Communication skills training for oncology professionals. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1242-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bickell NA, Adelson KB, Gonsky JP, et al. Does training oncologists to have goals of care discussions increase and improve the quality of GoC discussions with advanced cancer patients? J Clin Oncol 2018;36:6597. [Crossref]

- VitalTalk. Available online: https://www.vitaltalk.org/. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- Bernacki R, Hutchings M, Vick J, et al. Development of the Serious Illness Care Program: a randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009032. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lelorain S, Brédart A, Dolbeault S, et al. A systematic review of the associations between empathy measures and patient outcomes in cancer care. Psychooncology 2012;21:1255-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zachariae R, Pedersen CG, Jensen AB, et al. Association of perceived physician communication style with patient satisfaction, distress, cancer-related self-efficacy, and perceived control over the disease. Br J Cancer 2003;88:658-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2004;90:2297-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, et al. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol 2010;29:160-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Back A, Arnold R, Tulsky J. Mastering Communication with Seriously Ill Patients : Balancing Honesty with Empathy and Hope. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

- Carlson LE, Bultz BD. Cancer distress screening: Needs, models, and methods. J Psychosom Res 2003;55:403-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Place M. Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer Cancer Service Guidance Supports the Implementation of The NHS Cancer Plan for National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2001. Available online: www.doh.gov.uk/cancer/cancerplan.htmwww.doh.gov.uk/cancer/pdfs/calman-hine.pdfWeb:www.nice.org.uk. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Zabora J. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology 2001;10:19-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okuyama T, Endo C, Seto T, et al. Cancer patients’ reluctance to disclose their emotional distress to their physicians: a study of Japanese patients with lung cancer. Psychooncology 2008;17:460-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor S, Harley C, Campbell LJ, et al. Discussion of emotional and social impact of cancer during outpatient oncology consultations. Psychooncology 2011;20:242-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heaven CM, Maguire P. Disclosure of concerns by hospice patients and their identification by nurses. Palliat Med 1997;11:283-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hardman A, Maguire P, Crowther D. The recognition of psychiatric morbidity on a medical oncology ward. J Psychosom Res 1989;33:235-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer 2001;84:1011-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cape J, Barker C, Buszewicz M, et al. General practitioner psychological management of common emotional problems (I): Definitions and literature review. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:313-8. [PubMed]

- Ryan H, Schofield P, Cockburn J, et al. How to recognize and manage psychological distress in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005;14:7-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butow PN, Brown RF, Cogar S, et al. Oncologists’ reactions to cancer patients’ verbal cues. Psychooncology 2002;11:47-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oguchi M, Jansen J, Butow P, et al. Measuring the impact of nurse cue-response behaviour on cancer patients’ emotional cues. Patient Educ Couns 2011;82:163-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5748-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams K, Cimino JE, Arnold RM, et al. Why should I talk about emotion? Communication patterns associated with physician discussion of patient expressions of negative emotion in hospital admission encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89:44-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lussier MT, Richard C. Handling cues from patients. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:1213-4. [PubMed]

- Morse DS, Edwardsen EA, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1853-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sep MSC, van Osch M, van Vliet LM, et al. The power of clinicians’ affective communication: How reassurance about non-abandonment can reduce patients’ physiological arousal and increase information recall in bad news consultations. An experimental study using analogue patients. Patient Educ Couns 2014;95:45-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jansen J, van Weert JC, de Groot J, et al. Emotional and informational patient cues: The impact of nurses’ responses on recall. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79:218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Back AL, Trinidad SB, Hopley EK, et al. What patients value when oncologists give news of cancer recurrence: commentary on specific moments in audio-recorded conversations. Oncologist 2011;16:342-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Platt FW, Keller VF. Empathic communication: a teachable and learnable skill. J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:222-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Del Piccolo L, Bensing J, et al. Coding patient emotional cues and concerns in medical consultations: The Verona coding definitions of emotional sequences (VR-CoDES). Patient Educ Couns 2011;82:141-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beach WA, Easter DW, Good JS, et al. Disclosing and responding to cancer “fears” during oncology interviews. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:893-910. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:593. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliat Med 2002;16:297-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al. Communicating with realism and hope: incurable cancer patients’ views on the disclosure of prognosis. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:1278-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lind SE, DelVecchio Good MJ, Seidel S, et al. Telling the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:583-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2007;21:507-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koedoot CG, Oort F, de Haan R, et al. The content and amount of information given by medical oncologists when telling patients with advanced cancer what their treatment options are: palliative chemotherapy and watchful-waiting. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:225-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ Expectations about Effects of Chemotherapy for Advanced Cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen AB, Cronin A, Weeks JC, et al. Expectations about the effectiveness of radiation therapy among patients with incurable lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2730-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4387-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1203-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Smith TJ. Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2715-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:81-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, et al. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Intern Med 1998;129:441. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DesHarnais S, Carter RE, Hennessy W, et al. Lack of concordance between physician and patient: reports on end-of-life care discussions. J Palliat Med 2007;10:728-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Childers JW, Back AL, Tulsky JA, et al. REMAP: A Framework for goals of care conversations. J Oncol Pract 2017;13:e844-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maguire P, Pitceathly C. Key communication skills and how to acquire them. BMJ 2002;325:697-700. [Crossref] [PubMed]