Quality of care, spirituality, relationships and finances in older adult palliative care patients in Lebanon

Introduction

Palliative care is holistic multidisciplinary care that can prevent and relieve suffering through the early identification, assessment, and treatment of pain and other physical, psychological or spiritual problems. By doing so, palliative care would ultimately improve the quality of life (QoL) of patients with life threatening illness and their families (1).

In Lebanon, palliative care exists in the form of several non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and as units within hospitals. Patients with life-threatening illnesses are usually referred to these NGOs by their physicians or a social worker (2,3). Free of charge care is offered to patients from the comfort of their own homes with a focus on pain and symptom management. Medical, social and psychological challenges are holistically approached to maintain and preserve patients’ dignity (3).

Specifically, the older adult population requires palliative care in the last phase of life. They are burdened with chronic comorbidities, loss of functional independence, and possible cognitive decline and frailty. Treatment decisions become complicated, symptom management becomes difficult, and many psychosocial problems and spiritual suffering come into the mix (4). However, only 16% of specialist palliative care provision is provided to patients over 85 years old (5) despite the increasing numbers of the worldwide ageing population. The number of people aged 60 and above was 962 million in 2017 and is projected to more than double at 2.1 billion in 2050 (6). Furthermore, the current number of older adults above the age of 80 is expected to triple by 2050 and reach seven times its value in 2100 at 909 million. Specifically, the Lebanese population aged 60 and older was estimated at 12% in 2017 (6).

The lack of provision of palliative care for older adults is the initial failure in providing quality care. A study conducted by Sampson et al. (7) shed light on this by reporting a mere 28% of the 81% of deaths in a sample of chronic dementia patients as having received palliative care consultations; this was despite the prevalence of chronic pain and psychiatric symptoms that necessitated specialist healthcare provision (7). A study conducted on older adult cancer patients in Sweden showed that younger patients were more likely to receive symptom relief, palliative care consultation, and information about death and disease prognosis than their older counterparts. Moreover, old age was found to be a risk factor for poor end of life (EOL) quality of care (8).

When palliative care is indeed provided, one would have to examine the quality of this care. For quality care to be provided, a multidisciplinary team must function together as a whole and be financially and medically accessible to the patient. Moreover, communication is a key component in quality palliative care; transferring patient information and allowing shared decision making, healthcare providers listening to patients and the establishment of rapport are all important elements in the provision of quality palliative care. Individualized holistic care, encompassing physical symptoms, social symptoms, and psychological symptoms, is also another main staple of quality of care (9). Older patients receiving palliative care tend to rate the quality of care provided as poorer compared to their younger counterparts (10) where a lack of instruction on their disease status and prognosis, poor nursing supervision, and poor healthcare provider communication were reported as the main barriers to a good quality of care (11). Moreover, a study addressing palliative care among older adults showed that the quality of care provided was found to be poor as evidenced by a lack of understanding of their condition (12).

This was further established in a study comparing the quality of palliative care received at home, in the hospice and in the hospital. de Boer et al. (13) reported that the quality of hospital care had the lowest rating from family members and home care appeared to be the most favorable. Moreover, poor communication within teams was reported as the biggest barrier to quality in-hospital palliative care (14) with a striking 29.8% of family members of older adult in-patients in the United States reporting poor communication with clinicians (15).

Similarly, more than half of registered nurses (55.2%) perceived the quality of care provided to EOL patients in the hospital to be poor and identified aggressive treatment as a main factor (16). Other common barriers to quality palliative care were found to be: lack of educated young nurses, lack of communication between providers and family, poor symptom management, staff shortage and poor time allocation to patients, lack of privacy, family denial, lack of support from the organization, and an uncertain prognosis. In contrast, the best facilitators to improving the quality of care were ample time to prepare for death and healthcare providers who communicated and supported the patients and their families. A need for educating young nurses in specialized care and communication skills was identified alongside the need for religious experts (16).

Spirituality and religion are at the core of palliative care and tend to affect people’s beliefs about health, illness, and death. Religious involvement plays a key role in decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety among older adults hence lessening the impact of both symptoms on their QoL (17). Moreover, hospitalized older adults reported religious counseling as an important factor in EOL decisions; moreover, they identified religion as playing a key factor in major issues such as withdrawal of care and life and death decisions (18). In Lebanon, cultural sensitivity regarding religion is vital, especially when dealing with end-of-life issues, since most Lebanese, regardless of their religion, consider God as powerful, capable, the ultimate determinant, and the source of miracles (19).

Geriatric patients have expressed their need for family support to improve on their quality of care (11) making it alarming that increasing age is directly proportional to dying alone with older adults being four times more likely to die without the presence of a family member than younger ones (8). Social support is protective of positive health behaviors, and positive marital and familial relationships could give patients strength in having a shared decision maker regarding their situation. Moreover, a healthy family environment decreases levels of stress at the EOL and hence would improve patient perception on care quality (20). In addition, adequate social support is associated with caregivers of chronically ill patients having less financial difficulty in meeting basic expenses for items such as food and clothing (21). Therefore, it is important to take the family members and caregivers of chronically ill patients into consideration when planning and providing optimal quality of care.

In conclusion, older adults seem to be recipients of poor palliative care quality. Adequate clinician communication, familial support, and religious/spiritual support are identified as main factors in providing good quality of care. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the quality of palliative care among Lebanese hospitalized older adults aged 65 and above. This will raise the awareness of healthcare professionals, policy-makers, and the public on the need for palliative care services and their impact on the QoL of older adults, and as such will prepare the ground for policy change regarding palliative care at the national level.

Methods

Study design, setting & sample

The study design was cross-sectional with data collection occurring over a period of 2 years from 2015 to 2017. Hospitalized Lebanese older adults, 65 years and above, were recruited from three major medical centers in Lebanon. Further inclusion criteria included actually residing in Lebanon and needing basic palliative care. This care would be provided by geriatricians with palliative care experience at the time of data collection. Eligibility for inclusion was standardized by screening for altered cognition and palliative care need using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (22) and Necesidades Paliativas Centro Colaborador de la Organizacion Mundial de la Salud- Institut Catala d’Oncologia (NECPAL CCOMS-ICO) tools respectively (23). Candidates receiving a cut off score of 24 on the MMSE were found to be cognitively challenged and hence excluded from the study. This exclusion criterion was based on the self-reporting nature of the data collection tool. Another exclusion criterion, due to special population status, was patients who were actively dying.

The power calculation was done for the main study, which addressed the relationship between quality of life, symptom prevalence, and quality of care. A multiple linear regression including eight predictors and a moderate effect size of R2=0.13 was used to calculate sample size. The needed sample size was identified at 109 with a set power of 80% and an alpha of 5%. However, a larger sample size of 200 was suggested due to the intention to stratify based on age and gender (24). Participants were recruited into the study by key physicians in the three medical centers to obtain a convenience sample (N=203). When the physicians knew of a patient at their institution who would fit the criteria of the study, they informed them about the study. Only three of those approached refused participation due to poor health. Informed consent was obtained from participants by trained research assistants even before screening for eligibility. Then face-to-face interviews were performed by the research assistants who then filled the questionnaires. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the three medical centers involved and of the university where the study took place approved the study and all the investigators and research assistants involved were CITI certified.

Instruments

The end-points of the study are: the quality of palliative care in terms of median reported access to care, patient-clinician relationship, and clinician-clinician communication; the median reported spirituality/religiousness of patients and their sense of purpose; median reported patient relationships including friendships and social support; the median reported financial hardship during the illness; and QoL score.

Quality of care was measured using 20 selected items from the original survey of the Needs at the End of life Screening Tool (NEST) and the final 13 item tool (25,26). The authors were given permission to translate the chosen items to Arabic and then utilize them. The different domains of this tool have demonstrated adequate content and construct validity. Moreover, internal reliability was found to be good with Cronbach’s α coefficients ranging from 0.64 to 0.86 (25). The interview included questions covering financial burden (3 items), medical care (8 items), spirituality (5 items) and relationships (4 items). Questions were answered on a Likert scale with a range of 1-10. High scores on the financial burden and relationship scale indicated higher financial difficulties and better social relationships. The quality of care section included the 8 items pertaining to medical care in addition to two items from the relationships section. These items are: “You feel that your doctor/nurse listens to what you have to say about your illness or medical treatment” and “You have difficulty telling the doctor/nurse how you feel”. Three sub-categories were then formed: access to care, patient-clinician communication and clinician-clinician communication. High scores on all the items in the three categories, except two, indicated agreement with the question. The two exceptional items were: “How much do you feel your doctors and nurses respect you as an individual?” and “How clear is the information from the medical team about what to expect regarding your illness?”; a score of 1 meant “completely” and a score of 10 “not at all” hence higher scores indicated poorer outcomes.

Spirituality and religiousness high scores were indicative of strong agreement with the brought forth concept except one item: “How much does religious belief or spiritual life contribute to your sense of purpose?” A score of 1 meant “a great deal” and a score of 10 meant “not at all”, hence high scores represented poor outcomes.

QoL was measured using he European Organization for Research & Treatment of Cancer (EORTC-QLQ C-30) tool. The Global Health Status sub-scale was the measure adopted from this tool; it included 2 items: overall quality of health as perceived by the patient and QoL measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1, very poor; 7, excellent) (27). The Arabic version of the EORTC displayed good validity. Internal reliability was also good with six out of nine subscales displaying Cronbach’s alpha coefficients greater than 0.70 (28).

Sample characteristics included socio-demographic variables (age, educational status, and marital status). Different subgroups of educational status and marital status were clustered in two groups each and these were used in data analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations and frequencies were used to summarize the characteristics of the study sample. Quality of care (access to care, patient-clinician relationship, and clinician-clinician communication), spirituality/religiousness, patients’ relationships and the degree of financial hardship during the illness were summarized by means, medians, standard deviations and ranges of relevant items in the corresponding instruments.

Results

Sample characteristics

The background characteristics of the 203 participants are as follows: mean age of the sample was 78.61 (SD=7.73) with the majority being males (59%) and married (68%). Patients with elementary education versus those above elementary education were distributed almost equally at 51% and 49% respectively. Low QoL scores were apparent at 35.43/100 (SD=23.45).

Quality of palliative care

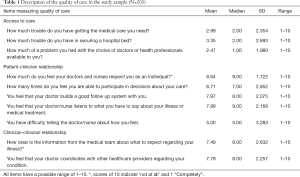

As displayed in Table 1, patients reported easy access to care expressed by low median item scores ranging from the lowest 1.0 pertaining to lack of a problematic doctor choice to the highest 2.0 for ease of securing a hospital bed. In patient-clinician communication patients reported feeling a lack of respect as individuals from their doctors and nurses with a high median of 9.0. Difficulty expressing their feelings to their healthcare providers had an average median of 5.0. The rest of the items indicated good communication ranging from a median of 7.0 for participation in care decisions to 9.0 for the degree to which care providers listened to what patients had to say. Finally, clinician-clinician communication had a mixed presentation with a high median of 8.0 indicating a lack of clarity in the information presented by healthcare providers to patients pertaining to their illness. On the other hand, patients felt that doctors coordinated well with other healthcare providers regarding their illness with a median score of 8.0.

Full table

Spirituality/religiousness

Table 2 displayed that patients considered themselves to be highly religious or spiritual with a median score of 9.0. In contrast, religious belief or spiritual life did not contribute much to their sense of purpose with an equally high median score of 9.0. The patients did not feel that their illness was senseless and meaningless (median =3.0), however, they did not feel that they could make anything good come from their illness with a low median score of 3.0. Patients were inclined to becoming more religious or spiritual after their illness with a median score of 7.0.

Full table

Relationships & financial hardships

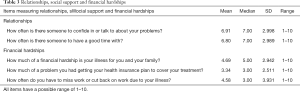

Table 3 presented information indicating an above average social support system for the patients with median scores of 7.0 for both the items pertaining to having someone to enjoy time with and to having a confidant available. There appeared to be minimal financial hardships with low median scores of 3.0 for having difficulties in acquiring insurance for health coverage and having to miss work due to illness. A median score of 5.0 was apparent for the item pertaining to financial hardship incurred on the family due to illness.

Full table

Discussion

Our study brought forth novel information about the perspective of older adults on the quality of care that they receive. Main findings in our study as perceived by patients were: ease of access to medical care, a lack of respect from clinicians, and poor communication of disease related information. No financial hardships were found in this study sample and social support and relationships were perceived to be favorably present. Spirituality appeared to increase after the diagnosis of disease.

It was noticeable that an ease of access to medical care and low financial difficulties were reported comparable to a study on Lebanese pediatric oncology patients and their parents where good quality medical care was identified (29). A study performed in the United States on Medicare geriatric patients showed that poverty and a lack of insurance were directly related to poor access to medical care (30). This leads the authors to believe that having low financial hardships must have facilitated the access to medical care for this study’s sample of palliative care patients. We would therefore recommend that insurance coverage for palliative care patients be maintained.

Patients felt a lack of respect as individuals from clinicians with a high item median score of 9/10 but they did feel like they were able to participate in their care plan. Unclear information from clinicians to patients regarding their illness was reported with a median of 8/10. Similarly, 29.8% of family members of older adult in-patients in the United States reported poor communication with clinicians (15). A model called “The Palliative and Therapeutic Harmonization (PATH)” was introduced to guide medical and surgical decision-making in frail older adults in Canada and it was concluded that palliative care programs tailored to fit the needs of frail older adults help improve the care offered to them by guiding them and their caregivers to make sound decisions. This would ultimately spare them from unnecessary suffering caused by futile and aggressive measures (31). Patients in our study felt that clinicians coordinated well amongst each other regarding the patients’ illness unlike other studies where a lack of good clinician coordination was identified as a main barrier to good quality of care (14,16). The authors recommend the introduction of continuous communication skills training for healthcare providers into palliative care models; this could improve on the lack of respect and poor information-sharing apparent in this sample.

The patients in our sample were found to be religious/spiritual at baseline. They felt that their illness had some sort of purpose however they did not feel that they could make anything good come out of it. Overall, our patients felt that they had become even more religious/spiritual after their illness. Ultimately, geriatric patients have been found to value spiritual care and have identified a highly important need to be respected as an individual. Moreover, the presence of spiritual suffering could significantly impact patient and family QoL and is a critical aspect to avoid when aiming for good palliative care delivery (32). It is therefore recommended that spiritual care be integrated in the patients’ overall plan of care to avoid spiritual suffering and to ensure the delivery of quality palliative care and improve QoL. Hence, the use of religious leaders could be a highly important aspect, given the important role they have been found to play in decision making in hospitalized palliative care patients (18).

Our sample had a moderate to good support system with patients reporting having someone to talk to (median =7.0) and have a good time with (median =7.0) most of the time. This is somewhat better than what another study reported about older adults being four times more likely to die alone than their younger counterparts (8). Older adults have reported their wishes to have good social support. This leads the authors to recommend the integration of family members into the patients’ care to strengthen the quality of that care (11).

Conclusions

Overall, care provided by a comprehensive and well-coordinated team improves QoL and satisfaction with care. For quality palliative care to be provided, certain aspects need to be present at the three levels: first, at the macro-level, a supportive policy and environment for quality palliative care needs to be ensured. Second, at the meso-level, multidisciplinary team resources and proper disease assessment and prognosis allocation need to be implemented (14). Finally, at the micro-level, effective communication, proper staff training, emotional, spiritual, and social support, and personalized care need to be provided (14).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the three medical institutions for their cooperation and the physicians and nurses for their help.

This work was supported by the Lebanese National Center for Scientific Research.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the three medical centers involved and of the university where the study took place approved the study and all the investigators and research assistants involved were CITI certified. Informed consent was ensured for all the participants in this study.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer control. Knowledge into action. Who guide for effective programmes. Palliative Care. Switzerland: WHO Press, 2007. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/publications/cancer_control_palliative/en/, 2018.

- Balsam. What We Do. Available online: Accessed 7/5, 2019.https://balsam-lb.org/what-we-do/#patients.

- SANAD. The Home Hospice Organization of Lebanon Annual Report. Available online: https://itsaboutlife626580192.files.wordpress.com/2018/04/sanad-2017-annual-report-online.pdf

- Voumard R, Rubli Truchard E, Benaroyo L, et al. Geriatric palliative care: a view of its concept, challenges and strategies. BMC Geriatrics 2018;18:220. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keeble M. 'Do I have to have cancer to get better care?' Improving palliative care provision for frail older people. Int J Palliat Nurs 2015;21:409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. ESA/P/WP/248. 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-the-2017-revision.html

- Sampson EL, Candy B, Davis S, et al. Living and dying with advanced dementia: A prospective study of symptoms, service use and care at the end of life. Palliat Med 2018;32:668-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindskog M, Tavelin B, Lundstrom S. Old age as risk indicator for poor end-of-life care quality - A Population-based study of cancer deaths from the Swedish Register of Palliative Care. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:1331-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wentlandt K, Seccareccia D, Kevork N, et al. Quality of Care and Satisfaction With Care on Palliative Care Units. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:184-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sandsdalen T, Hoye S, Rystedt I, et al. The relationships between the combination of person-and organization- related conditions and patients' perceptions of palliative care quality. BMC Palliat Care 2017;16:66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Azad N, Lemay G, Li J, et al. Perspectives from geriatric in-patients with heart failure, and their caregivers, on gaps in care quality. Can Geriatr J 2016;19:195-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilkie P. Quality of care of the elderly towards the end of life. Qual Prim Care 2008;16:61-63. [PubMed]

- de Boer D, Hofstede JM, de Veer AJE, et al. Prelatives' perceived quality of palliative care: comparisons between care settings in which patients die. BMC Palliat Care 2017;16:41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Threapleton DE, Chung RY, Wong SYS, et al. Care toward the end of life in older populations and its implementation fascilitators and barriers: a scoping review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:1000-1009.e4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khandelwal N, Curtis JR, Freedman VA, et al. How Often Is End-of-Life Care in the United States Inconsistent with Patients' Goals of Care? J Palliat Med 2017;20:1400-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Omar Daw Hussin E, Wong LP, Chong MC, et al. Nurses' perceptions of barriers and fascilitators and their associations with the quality of end-of-life care. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:e688-702. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang CY, Hsu MC, Chen TJ. An exploratory study of religious involvement as a moderator between anxiety, depressive symptoms and quality of life outcomes of older adults. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:609-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geros-Willfond KN, Ivy SS, Montz K, et al. Religion and spirituality in surrogate decision making for hospitalized older adulta. J Relig Health 2016;55:765-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bejjani-Gebara J, Tahshjian H, Abu-Saad Huijer H. End-of-Life care for Muslims and Christians in Lebanon. Eur J Palliat Care 2008;15:38-43.

- Carr D, Moorman SM, Boerner K. End-of-Life Planning in a Family Context: Does Relationship Quality Affect Whether (and With Whom) Older Adults Plan? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2013;68:586-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee Y, Zurlo KA. Spousal caregiving and financial strain among middle-aged and older adults. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2014;79:302-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramirez M, Teresi JA, Silver S, et al. Cognitive assessment among minority elderly: Possible test bias. Journal of Mental Health and Aging 2001;7:91-118.

- Gómez-Batiste X, Martínez-Muñoz M, Blay C, et al. Identifying patients with chronic conditions in need of palliative care in the general population: development of the NECPAL tool and preliminary prevalence rates in Catalonia. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:300-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polit DF, Beck CT. editors. Essentials of Nursing Research Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

- Emanuel LL, Alpert HR, Baldwin DC, et al. What terminally ill patients care about: toward a validated construct of patients' perspectives. J Palliat Med 2000;3:419-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Emanuel LL, Alpert HR, Emanuel EE. Concise screening questions for clinical assessments of terminal care: the needs near the end-of-life care screening tool. J Palliat Med 2001;4:465-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huijer HA, Sagherian K, Tamim H. Validation of the Arabic Version of the EORTC QLQ Quality of Life Questionnaire among Cancer Patients in Lebanon. Qual Life Res 2013;22:1473-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Gharib RM, Abu-Saad Huijer H, Drawish H. Quality of care and relationships as reported by children with cancer and their parents. Ann Palliat Med 2015;4:22-31. [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick AL, Powe N, Cooper L, et al. Barriers to health care access among the elderly and who perceives them. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1788-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moorhouse P, Mallery LH. Palliative and therapeutic harmonization: a model for appropriate decision-making in frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:2326-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puchalski CM. Spirituality in geriatric palliative care. Clin Geriatr Med 2015;31:245-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]