Mental health status of cancer research center’s care givers: should we worry?

Brief summary of current situation

There is currently very little information in the literature on the status of mental health of physicians practicing in cancer research centers, whereas medical activity has intensified in these centers, due to a growing patient’s population and number of annual cancers (1).

Many serious and chronic diseases are treated in these centers, where the care staff may suffer psychologically from the intense activity and the frequent lethal risk of some end disease patients.

Professional exhaustion status is best known as “burnout syndrome”, that was conceptualized for the first time by the American psychiatrist Freudenberger in 1975. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it is characterized by “a feeling of intense fatigue, loss of control and inability to achieve concrete results at work”.

Recent studies have shown a high prevalence of burnout syndrome among medical and surgical residents. Subgroup analysis by specialty showed that radiology (77.16%, 95% CI: 5.99–99.45%), neurology (71.93%, 95% CI: 65.78–77.39%), and general surgery (58.39%, 95% CI: 45.72–70.04%) were the top three specialties with the highest prevalence of burnout (2).

The consequences of this chronic and repetitive psychological pressure are serious, leading to a rate of depression and suicide that has increased in the recent years, and whose magnitude is currently underestimated among the medical community.

The psychological suffering of the medical staff is often expressed late and is not so easy to detect. Many factors often come into play, but all medical workers who are going through a period of exhaustion are under chronic stress. It is therefore an important vulnerability factor.

The vast majority have a high workload, plus one or more of the following voltage sources: lack of autonomy (do not participate in any or few decisions related to their task), imbalance between the efforts made and the recognition obtained from the employer or immediate superior (salary, esteem, respect), low social support: with the head or between colleagues, insufficient communication: from management to employees, regarding the vision and organization of the hospital (3).

In addition to these factors, individual peculiarities come into play. For example, it is unclear why people experience more stress than others. In addition, some attitudes (too much emphasis on work, perfectionism) are more common among individuals who are burned out. According to research, it seems that low self-esteem is a determining factor. In addition, certain life contexts, such as heavy family responsibilities or loneliness, can jeopardize work-life balance.

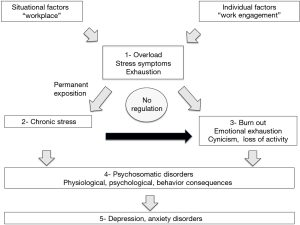

Regardless of the sources of stress at work, there is an imbalance between the pressure and the resources (internal and external, perceived or real) available to deal with it (Figure 1).

Burnout syndrome falls into the category of adjustment disorders. It is not recognized as a mental illness, and therefore does not appear in DSM-IV, the medical manual of mental disorders.

Diagnosis is difficult to establish because doctors do not have specific criteria. Thus, distinguishing burnout syndrome from depression is not easy.

A person in chronic stress constantly puts his body on alert. She produces too much stress hormones, mainly adrenaline and cortisol. Some people may experience anxiety, eating disorders, substance abuse problems or, in the extreme, suicidal thoughts.

Some workers are exhausted even to the point of leaving their lives. The Japanese term “karoshi” refers to sudden death from nervous exhaustion at work, caused by a heart attack. The phenomenon was observed for the first time in Japan in the late 1960s.

Widening our scope of enquiry: our experience

We conducted an anonymous informal survey in our cancer research center in Nice to assess the chronic stress of caregivers. A panel of all the caregivers was interviewed, including doctors (n=10), nurses (n=10), caregivers (n=5), stretcher bearers (n=3). Caregivers who wanted to answer completed a questionnaire anonymously, this survey was conducted in April 2019 in our Cancer Research Center in Nice. The results showed that the majority of respondents were not happy to come to work (60%) because of a workload that was considered too important, and psychological situations that were difficult to manage in the oncological environment. None had attempted suicide but 30% had already experienced black thoughts (suicidal thoughts) in the past 2 years.

This reflects the current state of medical malaise in medical centers in the fight against cancer where the workload required of doctors is always greater, the time spent on the patient shortens and the time for personal reflection almost non-existent.

This situation is quite alarming, and it seems that the awareness of the phenomenon is low.

If our current society demands ever more profitability, applied to the medical field it loses some meaning, where the human being, compassion and benevolence are supposed to prevail. We can legitimately ask ourselves how far this aberration will go.

Ignoring the suffering of the medical team does not serve the health system nor the patients, as this problem seems to be worldwide (4) and concerning both public and private hospitals (5).

Proposed strategy to overcome current difficulties

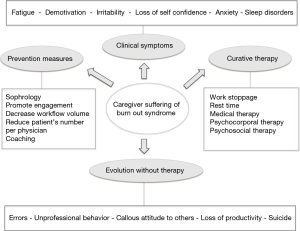

No one is immune to burnout in today’s medical structures. It is much better to prevent burnout syndrome than to have to cure it (Figure 2).

It is therefore necessary to quickly detect the first physical and psychological symptoms related to stress (fatigue, demotivation, irritability, loss of self-confidence, anxiety, sleep disorders). It is then necessary to look for the best possible social support in the workplace, to try to bring profitable transformations to the organization of work and, above all, to learn how to set personal limits (6).

Some centers have tried expressive arts interventions to address psychological stress in healthcare workers, and great improvements were seen in burnout, stress and emotional outcomes. The intervention characteristics included art-based, music-based and used storytelling or narrative (7).

Relaxing therapies such as Sophrology are already a valuable aid in the management of patients in oncology by reducing anxiety and pain, and can also be applied to health professionals (8).

Many previous studies have reported significant levels of burnout syndrome and depression in healthcare professionals. Some authors indicated a method of calibrating burnout against depression allowing burnout scores to be interpreted in terms of their impact on mental health, with high prevalences found. This point to an urgent need to rethink the psychological pressures of health professions education and daily work namely in cancer research institutes where the additional death impact is almost always present (9).

Burnout syndrome not only is a serious problem for health professionals, but it also adversely affects the quality and safety of health care for the patients they care for. A health professional with burnout may commit more errors, exhibit unprofessional behavior and a callous attitude to others, have diminished productivity, and cause other problems for the health care system (10).

In the context of burnout, the challenge will be to fight against the process of degradation of the subjective relationship to work, through three dimensions: fighting emotional exhaustion, cynicism about work, and decreasing personal accomplishment at work (11).

This caregivers’ reaction is a movement of self-preservation in response to the (emotional) demands of the job that the person can no longer cope with.

There are tools for the measurement and detection of burnout, validated scientifically, such as the Maslach burnout inventory (MBI) developed by Maslach and Jackson in 1981, the most used nowadays (12).

Burnout syndrome can be prevented by acting on psychosocial risk factors: health carers must be informed and sensitized so that they are in ability to detect any signals from colleagues or themselves, the employer must ensure the workload of each (interact with caregivers, ensure planning and taking leave, and in the event of an increase in the workload: set up monitoring indicators, which make it possible to observe whether the load is punctual or recurrent, if it is well distributed over time and between the workers) (13).

Guaranteeing strong social support is important: the social support of a caregiver is conditioned by the quality of interpersonal relationships with colleagues and superiors, the solidarity and trust existing between people, their competence and availability, the recognition of the work done, but also by the existence of groups or discussion and regulation spaces for medical workers. The idea is to discuss collectively, for example among peers, the work situations encountered by each other (14).

It is important to develop all forms of recognition and reward of work (financial, symbolic, statutory, etc.), and to ensure equity and fight against any form of injustice at work (15).

The care of a caregiver in burnout syndrome is to be adapted according to the severity of the associated symptoms. It is done in several times, including most often a work stoppage, allowing successively: rest, identity reconstruction, reflection and the rebirth of the desire to work, the possibility of returning to work (16).

Conclusions

There seems to be a growing psychological exhaustion within the medical community, associating personal and professional consequences in the oncological environment. The prevention of burnout syndrome should be carried out and its symptoms well known and recognized to improve the quality of life of caregivers and patients.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was approved by institutional ethics board of center Antoine Lacassagne (No. 2019/60). Written informed consent for the survey in this study was obtained for each participant.

References

- Lazarescu I, Dubray B, Joulakian MB, et al. Prevalence of burnout, depression and job satisfaction among French senior and resident radiation oncologists. Cancer Radiother 2018;22:784-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Low ZX, Yeo KA, Sharma VK, et al. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu TY, Chung PF, Liao HY, et al. Role ambiguity and economic hardship as the moderators of the relation between abusive supervision and job burnout: an application of uncertainty management theory. J Gen Psychol 2019;146:365-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Onofrio L. Physician burnout in the United States: a call to action. Altern Ther Health Med 2019;25:8-10. [PubMed]

- Miranda-Ackerman RC, Barbosa-Camacho FJ, Sander-Möller MJ, et al. Burnout syndrome prevalence during internship in public and private hospitals: a survey study in Mexico. Med Educ Online 2019;24:1593785. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Champ CE, Beriwal S, Smith RP. Physician burnout and physician health: three simple suggestions for a complex problem. Pract Radiat Oncol 2019;9:297-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phillips CS, Becker H. Systematic review: expressive arts interventions to address psychosocial stress in healthcare workers. J Adv Nurs 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertrand AS, Iannessi A, Buteau S, et al. Effects of relaxing therapies on patient's pain during percutaneous interventional radiology procedures. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:455-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick O, Biesma R, Conroy RM, et al. Prevalence and relationship between burnout and depression in our future doctors: a cross-sectional study in a cohort of preclinical and clinical medical students in Ireland. BMJ Open 2019;9:e023297. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harolds JA. Quality and safety in health care, part XLV: introduction to burnout. Clin Nucl Med 2019;44:221-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kansoun Z, Boyer L, Hodgkinson M, et al. Burnout in French physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2019;246:132-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaikh AA, Shaikh A, Kumar R, et al. Assessment of burnout and its factors among doctors using the abbreviated Maslach burnout inventory. Cureus 2019;11:e4101. [PubMed]

- Fred HL, Scheid MS. Physician burnout: causes, consequences, and (?) cures. Tex Heart Inst J 2018;45:198-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mohd Ismail MNB, Lindstrom Johnson S, Weaver SJ, et al. Factors influencing burn-out among resident physicians and the solutions they recommend. Postgrad Med J 2018;94:540-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andolsek KM. Physician well-being: organizational strategies for physician burnout. FP Essent 2018;471:20-4. [PubMed]

- Murali K, Makker V, Lynch J, et al. From burnout to resilience: an update for oncologists. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;38:862-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]