Expectation of the place of care and place of death of terminal cancer patients in Hong Kong: a hospital based cross-sectional questionnaire survey

Introduction

According to a recent research conducted by Chung et al., around 30% of people in Hong Kong preferred to die at home (1). However, in Hong Kong, more than 90% of patients die in hospital. Therefore, there is only a small proportion of people who wish to die at home can finally fulfill their wishes. In fact, helping people to achieve their preferred location of care and death is sometimes considered as important indicator of quality of end-of-life care (2).

The objective of this study was to investigate the preference of place of care and place of death of terminal cancer patients who had received palliative care services in Hong Kong. We would like to know whether their preferences are different from the general Hong Kong population. Besides, we would search for the reasons behind their preferences and try to find out the possible obstructing and relieving factors for choosing home death.

In this study, we defined “home” as a place where we were familiar and we often lived. Therefore, it included home and residential care home for the elderly (RCHE) in Hong Kong. This was a broader sense for definition of home. In fact, a local study showed that 35% of older people would prefer dying in their RCHE (3).

According to a systematic review, it suggested place of death resulted from an interplay of factors that could be grouped into 3 main domains: illness (type of disease, level of disability), individual (socio-demographic characteristics and patient’s preference) and environmental factors (health care input, social support and macro-social support) (4). A systematic review evaluated the determinants of home and nursing home death among adult patients with advanced, life limiting malignant or non-malignant illness (5). It stated that factors that facilitated home death included patients receiving multidisciplinary home palliative care services, cancer compared to other diseases, early referral to palliative care, worse functional status, not living alone, presence of an informal caregiver and caregiver coping. It also stated that factors that were associated with an increased likelihood of nursing home death included palliative care services available in nursing home, having completed advanced directive, patient or family preference for nursing home death, worse functional status (mainly bedbound), admission to hospital-based nursing home and a longer stay at nursing home (≥3 months) (5).

On the other hand, the review showed factors that decreased likelihood of home death included increase hospital admissions in the last year of life, admissions to a hospital with palliative care services and some diseases such as haematological cancers compared to solid tumors (5).

Moreover, RCHE staff in Hong Kong are also largely untrained in managing end-of-life patients (6). Geriatric and palliative care specialists available to RCHEs are also insufficient (6). This would become barrier of RCHE death.

There are also legal barriers for the patients who wish to die at home to fulfill their wishes in Hong Kong. If a patient chose to die at home, a registered practitioner needs to certify the patient death at home and fill in a Medical Certificate of the Cause of Death (Form 18) of the Births and Death Registration Ordinance (Chapter 174). The practitioner must have attended the patient within 14 days immediately prior to the patient’s death. However, in reality, there may not be medical practitioner available to do this. Moreover, the deceased’s family has to register a death within 24 hours at the Births and Deaths General Register Office. After death registration, a Certificate of Registration of Death (Form 12) will be issued. The family can move the dead body from home only with this Form 12. The relatives then need to notify the funeral planner for prompt transfer of dead body within 48 hours. Additional costs from funeral parlour transport and accommodation of the deceased may be a barrier to some deceased’s family who have financial difficulties. All these legal and administrative requirements are not familiar among the public and would be barrier for home death.

For the patients who die at home and no medical practitioner can certify death, they need to transfer to accident and emergency department (AED) by ambulance staff. However, the Fire Services Ordinance (Cap 95) in Hong Kong stipulates that resuscitation has to be carried out for their patients despite their wishes. Moreover, for those who lives in RCHE, the Coroner Ordinance (Section 4, Coroner Ordinance, Cap 504) demands all deaths in RCHEs (except nursing homes) be reported to the Coroner. Therefore, RCHEs are disinclined to allow an older resident to die in their premises. For those who lives in RCHEs (except nursing home), if they prefer to die at home, they also need to transfer to AED after death.

When the patients reaches AED, however, resuscitation can be exempted if the family members would bring along the orders of “Do-not-attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation” (DNACPR) (non-hospitalized) and advance directive documents (6).

There are also some other macro-social factors that become barrier for the patients who wish to die at home. For example, lack of death education which causes people have taboo to talk about death. Some people would also fear of depreciation of property value if a person dies at home (7).

Methods

This is a hospital-based cross-sectional questionnaire survey and was performed in the Palliative Care Unit of the Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong from 3 December 2018 to 10 January 2019. Ethnics Committee of the Hospital Authority Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Clusters has approved the research protocol.

Eligible participants were terminal cancer patients who followed up in outpatient palliative care unit. They had advanced cancer without further active oncological treatment including chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy and radical radiotherapy at the time of questionnaire completion. Only old case patients were recruited. Participation in the study was voluntary. Informed consent would be obtained.

Self-designed Chinese-language questionnaires were distributed to patients who agreed to join the study. Research assistants and/or their accompanying relative(s) would read the questionnaire and helped the patients to complete it. The content of the English version questionnaire is attached in the Supplementary (Supplementary file 1).

Questions 1–3 were to obtain the expectation of the place of care and place of death of the terminal cancer patients. From the population-based telephone survey by Dr. Chung et al. and a cross sectional survey conducted by Dr. Chu et al., they were used as references for setting question 1 to question 3 (1,3). Questions 4–7 were to obtain the reasons behind their preferences. From the literature review by Tang ST, he stated the different reasons patients chose to die at home. From a qualitative study conducted by Dr. Phongtankuel et al., they discussed different reasons why home hospice patients chose to be hospitalized finally (8). All these studies could be used as references for setting questions 4 to 7. Questions 8–11 were to obtain the facilitating and obstructing factors for home death. From the population-based telephone survey by Dr. Chung et al. and the presentation by Professor Yeoh EK, they studied different facilitating and obstructing factors for home death in Hong Kong (1,9). Moreover, from the systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Dr. Costa et al., they also stated different factors associated with increase or decrease likelihood of home death versus hospital death (5). All these could be used as references for setting questions 8 to 11. Questions 12–16 were to investigate whether the participants thought the issue of place of death was important and whether their preference had been communicated with family members and medical staffs. From the literature review conducted by Gomes et al., it stated that a clearer recognition of the patient’s preferences by both professional and informal carers were important for home death (4). Moreover, according to the survey study conducted by Tang et al., he found that around half the patients thought dying at the preferred place was very important (10). All these studies could be used as references for questions 12–16.

Demographic information, marital status, living arrangement, caregiver status, education level, religion, mobility, any symptom at time of questionnaire, any completion of advance directives or DNACPR forms (non-hospitalized), living environment (direct landing with lift or not), median time from initial diagnosis to questionnaire assessment, median time from palliative care unit referral to questionnaire assessment were all collected from medical records and electronic patient record system of the Hospital Authority.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 23 for Windows. Preference for home death, preference to die in palliative care ward and hospital acute ward were used as dependent variables. Univariate analyses were performed to examine the association of variables to different preferences. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data.

Results

One hundred and thirty eligible patients were identified during the study period. Overall 72 patients (55.4%) agreed to join the study. Forty-seven patients (36.2%) refused to join. Six patients (4.6%) were not physically fit and 5 patients (3.8%) could not communicate well with research assistants. These patients were not recruited into the study. Overall 4 patients (5.6%) had not completed the questionnaire.

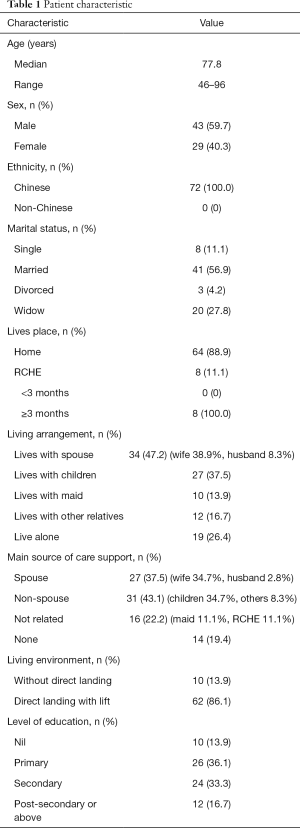

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the 72 patients were summarized in Table 1. The median age of the patients were 77.8 years old. Male to female ratio was around 3:2 (59.7% versus 40.3%). More than half of the patients married (41 patients, 56.9%). All of them were Chinese patients. Most of the patients lived at home (64 patients, 88.9%). Only 8 patients (11.1%) lived in RCHE. They all lived in RCHE for more than 3 months. Four patients lived in nursing home and 4 patients lived in non-nursing home. About one quarter of the patients (26.4%) lived alone and three quarter of the patients (73.6%) lived with relatives or maid. Around one fifth of the patients (19.4%) had self-care alone without any support. Fourth fifth of the patients (80.6%) would be cared by relatives, maid or RCHE staff.

Full table

Results of questionnaire

Expectation of the place of care and place of death of terminal cancer patients

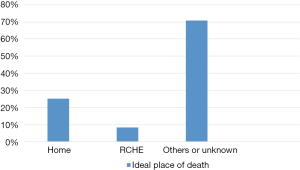

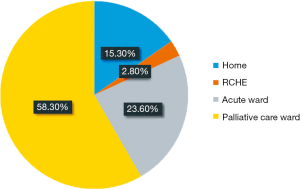

Among 72 patients who completed the questionnaire, ideally 18 patients (25.0%) wanted to die at home and 6 patients (8.3%) wanted to die in RCHE. As we considered both home and RCHE as “home”, total 22 patients (30.6%) wanted to die at home ideally. The result was shown in Figure 1.

However, after concerning reality and different choices, the result was shown in Figure 2. Only 11 patients (15.3%) wished to be taken care and died at home. Two patients (2.8%) wished to be taken care and died in RCHE. Concerning a broader sense of “home”, there were total 13 patients (18.1%) wished to be taken care and died at home.

Seventeen patients (23.6%) wished to extend the time to be taken care at home or at RCHE, but when symptoms could not be controlled or rapid deterioration of the medical condition, they wished to be sent to hospital and died in acute ward.

On the other hand, 42 patients (58.3%) wished to extend the time to be taken care at home or at RCHE, but when symptoms could not be controlled or rapid deterioration of the medical condition, they wished to be sent to hospital and died in palliative care ward.

Concerning place of care, total 61 patients (84.7%) wished to be taken care at home and 11 patients (15.3%) wished to be taken care at RCHE.

Reasons behind the preferences of place of care and place of death

Reasons of wish to die at home or RCHE

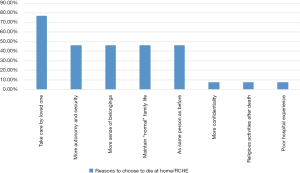

Concerning reasons of the 13 patients who chose to die at home or RCHE, the result was shown in Figure 3. Participants could choose more than one answer. The most frequent reason to choose home death was that patients could always to be taken care and accompanied by relatives and loved one (10 patients, 76.9%). Six patients (46.2%) chose home death because of more autonomy and security. Six patients (46.2%) chose because of more sense of belongings. Six patients (46.2%) chose because of hoping to maintain the “normal” family life as much as possible. Six patients (46.2%) chose because familiar surroundings and relationships confirmed the importance of the dying person and reaffirmed to the dying individuals that they were still the same people they always had been.

Reasons of wish to die in acute ward

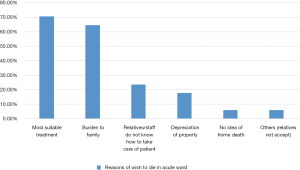

Concerning reasons of the 17 patients who chose to die in acute ward of hospital, the result was shown in Figure 4. Participants could choose more than one answer. The most frequent reason was that they thought they could receive the most suitable treatment in acute ward (12 patients, 70.6%). The second common reason to choose was that they thought they would bring a lot of pressure and became burden to family if they died at home (11 patients, 64.7%). Four patients (23.5%) chose because they thought their family or friends or old age home staff did not know how to take care of them.

Reasons of wish to die in palliative care ward

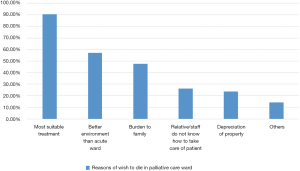

Concerning reasons of the 42 patients who chose to die in palliative care ward, the result was shown in Figure 5. Participants could choose more than one answer. The most frequent reason was that they thought palliative care service was the most suitable treatment to them (38 patients, 90.5%). Twenty-four patients (57.1%) chose because environment of palliative care ward was better than acute ward. Twenty patients (47.6%) chose because they thought they would become a burden to his family if they died at home.

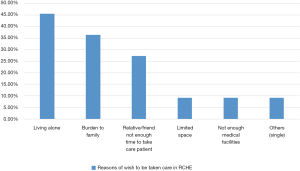

Reasons of wish to be taken care in RCHE

Concerning reasons of the 11 patients who wished to be taken care in RCHE, the result was shown in Figure 6. Participants could choose more than one answer. Two patients missed to answer this question. The most frequent reason of wish to be taken care in RCHE was living alone (5 patients, 45.5%). The second most frequent reason was that they would become a burden to their family if they died at home (4 patients, 36.4%). Three patients (27.3%) wished to be taken care at RCHE because their family or friends did not have enough time to take care of them.

Facilitating and obstructing factors for home death

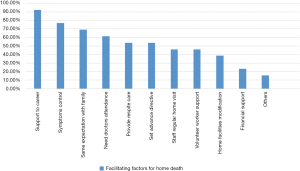

Facilitating factors for home death

Concerning the 13 patients who chose to die at home/RCHE in real life situation, Figure 7 showed the results of different facilitating factors for home death that were chosen by them. Participants could choose more than one answer. The most common chosen facilitating factor for home death was to provide enough support to the carers (12 patients, 92.3%). The next common chosen facilitating factor for home death was “symptoms can be controlled at home or RCHE” (10 patients, 76.9%). The third most common chosen facilitating factor for home death was “my family and I had the same expectation of my place of care and death” (9 patients, 69.2%).

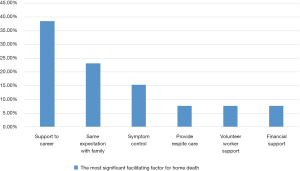

The most significant facilitating factor for home death

The most significant facilitating factor for home death chosen by participants was shown in Figure 8. Five patients (38.5%) chose “enough support to carers” as the most significant facilitating factor for home death. Three patients (23.1%) chose “my family and patients had the same expectation of place of care and death”. Two patients (15.4%) chose “symptoms can be controlled” as the most significant facilitating factor.

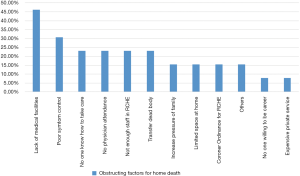

Obstructing factors for home death

Concerning the 13 patients who chose to die at home/RCHE in real life situation, Figure 9 shows the results of different obstructing factors for home death that were chosen by them. Participants could choose more than one answer. Two patients had not answered these 2 questions. The different obstructing factors chosen by the participants were with more or less similar frequency. The most common chosen obstructing factor for home death was “there were not enough medical facilities inside the house” (6 patients, 46.2%). The second most common chosen obstructing factor for home death was “worry symptom could not be relieved at home or RCHE” (4 patients, 30.8%). The third most common chosen obstructing factor for home death was “my family and friends did not know how to take care of me” (3 patients 23.1%), “physician must have attended patients within 14 days prior to death and to certify patient death at home” (3 patients, 23.1%), “there was not enough staff in RCHE” (3 patients, 23.1%) and “relatives needed to notify the funeral planner to transfer dead body to funeral parlor” (3 patients, 23.1%).

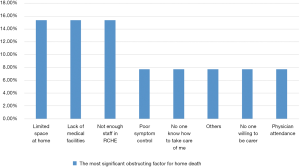

The most significant obstructing factor for home death

Factors chosen by participants as most significant obstructing factor for home death were also with more or less similar frequency. Result was shown in Figure 10. Two patients (15.4%) chose “small house with limited space”. Two patients (15.4%) chose “there were not enough medical facilities”. Two patients (15.4%) chose “there was not enough staff in RCHE to take care of me”. Since the patient number to answer these 2 questions was small, it was difficult to determine the most significant obstructing factor for home death in this study.

Communication with medical staff and family members

Around third fourth (53 patients, 73.6%) of the patients would tell family members about the expectation of place of death directly and around 50 patients (69.4%) knew family members had the same expectation of place of death as patient himself.

Around third fourth of the patients (55 patients, 76.4%) would tell doctors or nurses about the expectation of place of death directly and around 61 patients (84.7%) hoped doctors or nurses enquired directly about their expectation of place of death.

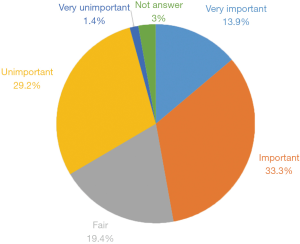

Importance of dying in the place according to patient’s wish

Ten patients (13.9%) thought that “dying in the place according to their wish” was very important. Twenty-four patients (33.3%) thought it was important. Fourteen patients (19.4%) thought it was only fairly important. Twenty-one patients (29.2%) thought it was unimportant and 1 patient (1.4%) thought it was very unimportant. Therefore, only around one half (50%) of the patients thought “dying in the place according to their wish” was important or very important. The result was shown in Figure 11.

Factors associated with choosing home death

Univariate analysis had been used to test any factors associated with the patients who chose home death. There was no statistically significant factor predicting the preference of home death. More than one caregiver was positively associated with preference of home death but statistically significant was not reached (P=0.126). Otherwise, patients who chose home death (the one who chose to die in RCHE and home) and the patients who chose hospital death were similar in age, gender, educational level, mobility, symptoms at questionnaire assessment, house with or without direct landing and received palliative home care service. Moreover, patients who chose to die at home (excluded patients chose RCHE) and patients who chose to die in hospital setting also had similar living arrangement (including lived with spouse only, lived alone and lived with caregiver).

Discussion

Expectation of place of death

From a systematic review (11), it showed that the mean preference of home death of terminal cancer patients was 59.9% (39.7–100%) (RCHE was not considered as home in these studies). Average preference of home death was 66% in European Studies while it was around 54.4% in Asian studies. In our study, after concerning reality and different choices, only 15.3% of patients chose home death (excluded patients who chose RCHE) as their best wishes. The rate was much lower than that in the international studies. This might be due to available and easily accessible palliative care service and in-patient services, different cultural factors and many obstructing factors in Hong Kong. This would be elaborated more at the discussion below.

Furthermore, as previously mentioned, around 30% of Hong Kong general population preferred to die at home (1). In our study, we aimed to investigate the preference of home death in terminal cancer patients who had received palliative care service. From Chung et al., it showed that older patients would have lower preference to die at home (1). Twenty-three point three percent of population at age of 70 to 79 preferred home death while 57% of age 30 to 39 preferred this. In our study, the median age of cancer patients were 77.8 years old and 25% of them wished to die at home ideally. Therefore, the result was quite compatible with the study that investigated in the general population. However, after concerning reality and different choices, only 15.3% of terminal cancer patients wished to die at home. Therefore, around 38% of patients changed their mind after concerning reality. Neergaard et al. reported that one quarter of all patients who preferred home death in the beginning changed their mind during time away home death (12). In our study, among the 8 patients who changed their preference after concerning reality, we had phone contacted them for possible reasons. Three of them were due to living alone and no family members could take care of them. One of them did not want to become burden of family members. One patient lived in RCHE but she preferred to die at home, however, no relatives had enough time to take care of her. Three of them were due to unknown reason. Therefore, most of the reasons to change their preferences were due to social factors.

Among the 8 patients who lived in RCHE, 2 (25.0%) patients wanted to die at RCHE. Although the total number of patients who lived in RCHE were low, the proportion of patients who wished to die at RCHE was still similar as the previous studies in Hong Kong.

In our study, palliative care ward became the most preferred place of death (58.3%). From a study, it determined the preference of place of death in London, Dublin and New York where all three places were with developed specialist palliative care (13). In that study, home was the most preferred place of death (56%), followed by inpatient palliative care or hospice unit (22%). On the other hand, hospice or palliative care unit was rarely least preferred (4%). Therefore, it showed that palliative care unit or hospice was still chosen as a common preferred place of death in cities where specialist palliative care was well developed.

Expectation of place of care

In our study, 61 patients (84.7%) wished to be taken care at home and 11 patients (15.3%) wished to be taken care at RCHE. For the patients who wished to be taken care in RCHE, the most common reason was due to living alone (45.5%). For the 59 patients (81.9%) who wished to die in hospital setting, they still wished to extend the time to be taken care at home or RCHE before admission to hospital. Therefore, extending the time of the patients to be taken care at home or RCHE should be our aim in the future.

Reasons of wish to die at home or RCHE

The most common reason to choose home death was that patients could always to be taken care and accompanied by relatives and loved ones (76.9%). Therefore, even for dying patients in hospital setting, more flexible visiting hours by relatives or friends was important.

Reasons of wish to die at hospital setting

Among 59 patients who wished to die at hospital setting, 50 patients (69.4%) thought that they could receive the most suitable treatment in acute ward or palliative care ward. In fact, in Hong Kong, the nursing and medical professional support to die at home was not enough. On contrary, medical care in hospital setting was easily assessable and the medical cost of public hospital was low. Moreover, for our terminal cancer patients who followed up in palliative care clinic, they could easily be admitted to palliative care ward if medical condition deteriorated. Therefore, this would lead to most patients wished to die in hospital setting in Hong Kong.

From a Cochrane database of Systematic Review in 2016, it included studies of mostly advanced cancer patients. Meta-analysis showed that home palliative care services could increase odds of dying at home (14) [odds ratio (OR) 2.21, P=0.003]. Moreover, from a systematic reviewed by Gomes et al., it showed that use and intensity of home care was associated with home death (4). This effect was found to be more significant in the last weeks of life (15,16). In Hong Kong, virtual ward program had been launched since 2011 by Hospital Authority. The concept of virtual ward was a new model of care that was pioneered in 2004 in United Kingdom (17). The aim was to provide patients at high risk of hospital readmissions with intensive multidisciplinary services in their own homes, thereby reducing hospital readmissions. Patients admitted to the virtual ward were visited by community nurses for the delivery of routine nursing care normally provided in the hospital. Physicians and other allied health care professionals might also be involved. Virtual ward program resulted in a reduction in the length of hospitalization compared to inpatient care in a systematic review (18). Although virtual ward program in Hong Kong was still run in small scale, it was already a good start in Hong Kong. We hoped that the service of virtual ward program could be expanded in the future and collaboration with oncologist was a possibility.

Moreover, total 31 patients (43.1%) chose to die in hospital setting because they thought they would become burden to family if they died at home. A cross-sectional questionnaire survey done among Chinese showed good death meant good relationship with family, good relationship with medical staff and not being burdens to others (19). The culture of Chinese was usually from relational perspective. In order to maintain good relationship with family members, patients might choose to die in hospital setting rather than in home setting.

Total 13 patients (18.1%) chose to die in hospital setting because they were fear of depreciation of the property value of their house if they died at home. This was quite similar as that seen in the study by Chung et al. (1). This was one of the macrosocial factors that needed to be changed in the future to facilitate home death in Hong Kong.

Facilitating factors and obstructing factors for home death

Different individual had different needs, therefore, we needed to find out the facilitating and obstructing factors which were specific to that particular patients, so that we could help them to fulfil their wish.

Facilitating factors for home death

In our study, the most common chosen facilitating factor for home death was to provide enough support to the carers (12/13, 92.3%). This factor was also chosen as the most important facilitating factor for home death with highest frequency (5/13, 38.5%). However, since still less than half of the patients chose this as the most significant factor, we could just consider it as one of the most significant facilitating factors for home death.

We needed to provide enough support to the caregiver, for example, providing teaching courses and respite care to the carers. The carers could also contact palliative home care nurse whenever were needed. Volunteer workers could provide psychological and practical support to carers. Moreover, tele-homecare was used in the United States, Canada, Japan and Europe (20-22), so that carers could easily assessable to the medical information whenever they needed. There were also compassionate care benefits, in the form of a paid leave for carers of dying patients implemented by the Canadian government since January 2004. All these services support could be considered in Hong Kong.

To support the elderly persons who lived in RCHE, a program called “Enhance community geriatric assessment team support to end-of-life patients in residential care homes for the elderly” was implemented by the Hospital Authority in Hong Kong since October 2015 (6). In the program, the Community Geriatric Assessment Team (CGAT) would collaborate with palliative care specialists who would provide training to the RCHE and CGAT staff.

The second common chosen facilitating factor for home death was “symptoms could be controlled at home or RCHE” (10/13, 76.9%). The virtual ward program mentioned before might help for better symptom control because the community nurse or doctors could have more frequent home visit and provided medication adjustment whenever was needed, although up to now, subcutaneous opioid was not allowed at home or RCHE. In RCHE, palliative care specialists would hold regular case conferences with the CGAT and assisted in complex case management. This would also help to improve symptom control of the elderly in RCHE (6).

The third common chosen facilitating factor for home death was “my family and patient had the same expectation of the place of care and death” (9/13, 69.2%). According to the review by Gomes et al, a clearer recognition of the patient’s preferences by both professional and informal carers were important as they would mobilise resources to fulfil that wish (4). Interestingly, it seemed that the family caregivers’ preference of death place to the patients’ had higher influence than the patients’ own preference. Hsieh at al. showed that most death places among cancer patients were not congruent to their wish (56.62%), while the actual place of patient’s death was congruent with the family’s preference (69.57%) (23). In our study, around one fourth (23.6%) of the patients would not tell directly family members about the expectation of place of death and around one fourth (27.8%) did not know the expectation of family members. Moreover, around one fifth (20.8%) of patients would not tell doctors or nurses directly about expectation of place of death. Therefore, the communication between patients with medical staff and the communication between patients with family members needed to be enhanced. Most of the patients (61/72, 84.7%) hoped doctors or nurses enquired directly about their expectation of place of death. Therefore, it was good for medical staff to discuss the issue of preference of place of death with patients during advance care planning.

Obstructing factors for home death

The most common and the most significant chosen obstructing factors for home death could not be determined by this study. However, for the patients who changed their preferences after concerning reality, most of them were due to living alone or no one can take care of them (5/8, 62.5%) As the family social support was not an easily modifiable factor, therefore, not every patient was suitable to die at home.

Importance of dying in the place according to patient’s wish

Tang et al. presented the mean score for the importance of dying at the preferred place of death rated by the patients to be 4.2 on a 5-point Likert scale, and more than half of the patients (52%) rated importance to 5/5 points (10). However, in our study, the mean score was only 3.2 and only 14% of the patients thought dying in place was very important. We did not know the reasons behind. But the proposed reason might be due to low rate of preference of home death and they thought they would die in hospital setting as expected.

Factors associated with choosing home death

According to Choi et al. 2005, the study showed that gender, place of residence, time since initial diagnosis and caregiver’s preference were all associated with preference of death place (24). In our study, there was no statistically significant factor predicting the preference of home death. The small sample size in this study limited statistical power to predict significant factors for preference of home death.

Limitation

As the sample size was not large in this study and the proportion of patients chose home death was small, this would reduce the power of the study to find out the commonest and most significant facilitating and obstructing factor for home death. It would also reduce the power to predict factors associated with preference of home death. In order to improve the sample size of the study, for those who chose hospital death could also be asked about the facilitating and blocking factors for home death. Moreover, in order to determine importance of different facilitating and blocking factors, participants could also give a score (e.g., Likert scale) for each factor. After excluding the patients who were physically unfit and uncommunicable, the participation rate was 60% which was more or less similar to that stated in the review with average participation rate 67.8% (11). Patients who agreed to participate in the study might constitute a bias sample. They might be more acceptable to their prognosis and be more open to talk about the issue of place of death. There were also missing data in the questionnaire although the proportion was not high. As it might not be easy for participants to understand the content of questionnaire and interpreted all the items correctly, it would be better if a trained person could assist the completion of questionnaire for each participant. Apart from that, most of the blocking factors were just opposite to the facilitating factors, therefore, in order to make the questionnaire simpler, we could just ask the blocking factor for home death. Concerning the future study, after at least 24 weeks, we would review the final place of care and death of these patients, any hospitalization and reason of hospitalization. We would also record the burden of symptoms before death. We hope all these would give us more information about the choice on home death.

Conclusions

The overall preference of home death of terminal cancer patients who received palliative care in Hong Kong was low compared to other international studies. This might be due to available and easily accessible palliative care service or inpatient service, different cultural factors and many obstructing factors in Hong Kong. Most of the patients wanted to be taken care at home as long as possible. Support to carers was the most common chosen relieving factor for home death and it was also chosen as one of the most significant relieving factors. It was inconclusive for the most common chosen and most significant obstructing factor for home death in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Dr. Kam-Hung Wong, Dr. Wai-Lim Leung, Miss Wai-Ming leung and Mr. Wai-Chi Leung for advice and support.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Rebecca Yeung and Tai Chung Lam) for the series “Integrating Palliative Medicine in Oncology Care: The Hong Kong Experience” published in Annals of Palliative Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm.2019.09.17). The series “Integrating Palliative Medicine in Oncology Care: The Hong Kong Experience” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by Ethnics Committee of the Hospital Authority Kowloon Central/ Kowloon East Clusters (Reference number: KC/KE-18-0239/ER-3).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Chung RY, Wong EL, Kiang N, et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Preferences of Advance Decisions, End-of-Life Care, and Place of Care and Death in Hong Kong. A Population-Based Telephone Survey of 1067 Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:367.e19-367.e27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Roo ML, Miccinesi G, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Actual and preferred place of death of home-dwelling patients in four European countries: making sense of quality indicators. PloS One 2014;9:e93762. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chu LW, Luk JK, Hui E, et al. Advance directive and end-of-life care preferences among Chinese nursing home residents in Hong Kong. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011;12:143-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:515-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Costa V, Earle CC, Esplen MJ, et al. The determinants of home and nursing home death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luk JK. End-of-life services for older people in residential care homes in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2018;24:63-7. [PubMed]

- Luk JKH, Liu A, Ng WC, et al. End-of-life care in Hong Kong. Asian J Gerontol Geriatr 2011;6:103-6.

- Phongtankuel V, Scherban BA, Reid MC, et al. Why do home hospice patients return to the hospital? A study of hospice provider perspectives. J Palliat Med 2016;19:51-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Choice of Dying at Home. Assessed on 21 July 2019. Available online: https://www.hospicecare.org.hk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/seminar-20161210-Yeoh-Eng-kiong.pdf

- Tang ST. When death is imminent: where terminally ill patients with cancer prefer to die and why. Cancer Nurs 2003;26:245-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nilsson J, Blomberg C, Holgersson G, et al. End-of-life care: Where do cancer patients want to die? A systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017;13:356-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, Sondergaard J, et al. Preference for place-of-death among terminally ill cancer patients in Denmark. Scand J Caring Sci 2011;25:627-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Daveson BA, Morrison RS, et al. Social and clinical determinants of preferences and their achievement at the end of life: prospective cohort study of older adults receiving palliative care in three countries. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:271. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013.CD007760. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grande GE, McKerral A, Addington-Hall JM, et al. Place of death and use of health services in the last year of life. J Palliat Care 2003;19:263-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fukui S, Fukui N, Kawagoe H. Predictors of place of death for Japanese patients with advanced-stage malignant disease in home care settings: a nationwide survey. Cancer 2004;101:421-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewis G. Virtual wards, real nursing. Nurs Stand 2007;21:64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shepperd S, Iliffe S. Hospital at home versus in-patient hospital care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005.CD000356. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haishan H, Hongjuan L, Tieying Z, et al. Preference of Chinese general public and healthcare providers for a good death. Nurs Ethics 2015;22:217-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Young NL, Barden W, Lefort S, et al. Telehomecare: a comparison of three Canadian models. Telemed J E Health 2004;10:45-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dansky KH, Palmer L, Shea D, et al. Cost analysis of telehomecare. Telemed J E Health 2001;7:225-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sachpazidis I, Stassinakis A, Memos D, et al. @HOME is a new Eu-Project in Tele Home care. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2002;47 Suppl 1 Pt 2:970-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsieh MC, Huang MC, Lai YL, et al. Grief reactions in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients in Taiwan: relationship to place of death. Cancer Nurs 2007;30:278-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi KS, Chae YM, Lee CG, et al. Factors influencing preferences for place of terminal care and of death among cancer patients and their families in Korea. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:565-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]