The prevalence of bereavement rooms at German hospitals: a cross-sectional observational study from 2016

Introduction

The majority of people wish to die at home (1-3). However, studies of the place of death show that the hospital is the most frequent place of death in western industrial countries (4-8). In Germany, slightly more than one percent of the total population dies each year. According to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany, 910,902 German citizens died in 2016 (9). Approximately one in two deaths (n=419,359) occurred at hospital (10). Consequently, taking care of dying patients and their bereaved relatives should be an important task for hospital staff.

For family members, friends and acquaintances, the loss of a loved one in hospital means a stressful and sometimes traumatic experience. In some cases, such as an accident or an embolic event, death occurs suddenly and unexpectedly. In other cases, such as cancer patients at an advanced tumor stage, death is predictable. In any case, bereaved relatives need protection, support, time and a private space to understand and to deal with the inevitable fact of death (11).

The way in which grieving relatives experience the last sight of the deceased and how the farewell is arranged can be of crucial importance concerning their attempt to cope with mourning. A dignified farewell can be remembered positively and thus make mourning easier. In contrast, negative impressions can make the grieving process extremely difficult (12,13).

In order to meet the need of next of kin for a dignified farewell, bereavement rooms have been set up in some hospitals. These rooms represent a specially designed morgue in the hospital for post-death care of a deceased patient. This room is usually located separately outside the wards. The aim is to ensure that relatives are professionally accompanied in their grief directly in the hospital and not only in the outpatient setting, for example in a funeral home. This should give them greater institutional support. As a special service, some obstetric departments also offer such a room especially for grieving parents who are confronted with miscarriage or stillbirth or for women and couples who have decided to have a late abortion.

To date, there are no official data concerning the frequency of bereavement rooms at German hospitals. Therefore, we have conducted the present study to obtain more detailed information on the prevalence of inpatient bereavement rooms. In addition, data on the frequency of use, location, equipment and organization of these rooms was collected.

Methods

Study design

The study is based on an observational cross-sectional study design. The observation period covers the year 2016.

Hospitals of interest

The investigation includes all German hospitals with more than 99 inpatient beds. We carried out this restriction for reasons of content and logistics. Although hospitals with less than 100 beds represent more than one third of all German hospitals (670/1,951), these medical institutions account for only 2% of the approximately 420,000 annual inpatient deaths in Germany (10). We hypothesized that only in a very small number of cases, a bereavement room would exist in hospitals <100 beds. From a methodological point of view, we were aware that this could possibly cause a selection bias. However, we estimated this probability of error to be rather low compared to the immense logistical effort that would have been required to include even smaller hospitals in our study.

According to the Federal Statistical Office, a total of 1,951 German hospitals existed on 31/12/2016 (10). Of these, 1,281 hospitals (65.6%) had more than 99 beds {inpatient beds [number of hospitals]: 100–199 [427], 200–399 [443], 400–599 [238], 600–799 [76], ≥800 [97]}. In addition, there were 380 hospitals offering obstetric care. Unfortunately, there was no official statistic regarding the number of beds in these special hospitals.

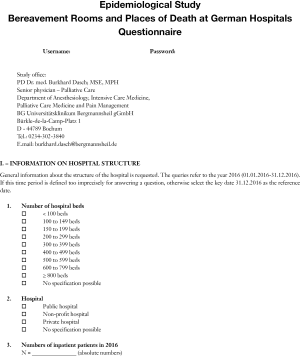

Study questionnaire

We contacted the medical directors of eligible hospitals. The hospital addresses and contact data were obtained from the German Hospital Directory, as well as via Internet search.

Study data were collected retrospectively using a questionnaire which had been developed for this purpose (see Appendix). We asked about the existence, location, equipment, and organization of bereavement rooms at German hospitals ≥100 beds. We also explicitly requested information about the existence of a bereavement room for parents who were confronted with miscarriage or stillbirth during hospital stays.

A bereavement room was defined as a specially designed morgue in the hospital in which relatives, friends and acquaintances bid farewell to a deceased patient in a private and dignified atmosphere.

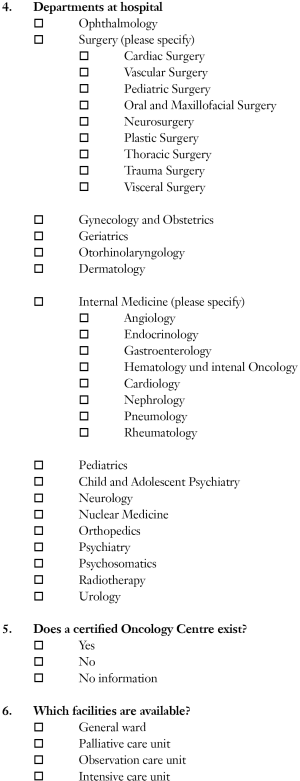

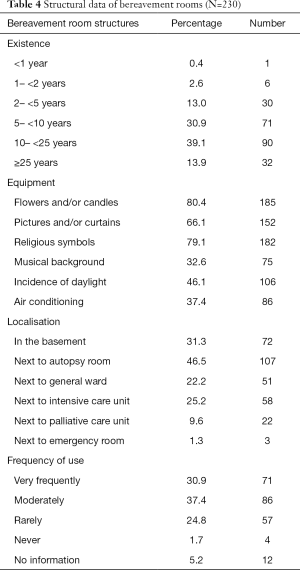

Data on the structure of the hospital and the absolute number of annual inpatient deaths were requested. If there was a bereavement room in the hospital, we asked for additional information: (I) duration of existence (<1, ≥1 to <2, ≥2 to <5, ≥5 to <10, ≥10 to <25, ≥25 years), (II) frequency of use (never, rarely, moderately, very frequently), (III) location (in the basement, next to an autopsy room, next to a general ward, next to an intensive care unit, next to a palliative care unit, next to an emergency room), (IV) equipment available in the farewell room (flowers and candles, pictures and/or curtains, religious symbols, background music, influx of daylight, air conditioning system for room cooling). We also asked whether a person or an organizational unit was assigned to take responsibility for the organizational processes of the bereavement room. If there was assigned responsibility, we asked about possible persons or hospital employees to whom this responsibility had been transferred (hospital pastoral care, nursing staff, hospital physicians, inpatient palliative care counselling service, employees of the department of pathology, hospital services such as reception or pick-up and delivery service, members of the ethics committee, employees of a funeral parlor, and/or volunteer hospice assistants).

The questionnaire was sent out to all medical directors by mail in September 2017 with the request for study participation. It was possible to answer the questions either in written mail form or online via Internet survey as well as by phone.

Statistical analyses

The results of the study were presented descriptively in absolute and relative numbers. To calculate the 1-year prevalence of existing bereavement rooms in hospitals [2016], a quotient (relative frequency) was calculated. The absolute number of inpatient bereavement rooms was noted in the numerator. Depending on the perspective of interest, either the absolute number of hospitals participating in our study or the absolute number of existing German hospitals ≥100 beds was entered in the denominator. Additionally, this procedure was carried out for hospitals with an obstetric department to determine the prevalence of bereavement rooms especially for deceased newborns and their grieving parents. From this quotient, we derived the one-year prevalence rate.

In relation to all German hospitals ≥100 beds, we methodically calculated a “minimum prevalence”. The term “minimum” indicates that only a subfraction of all possible German hospitals ≥100 beds participated in our study and that in reality an even higher number of bereavement rooms had to be expected.

The analyses were carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics program, version 24.0.

Ethics approval

The study was submitted to the Ethics Commission of the Ruhr-University Bochum and obtained ethics approval on 12th Sep 2017 (reference number 17-6067).

Results

Response rate

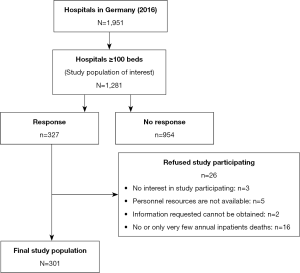

Of the 1,281 eligible hospitals, a total of 327 hospitals responded. Of these, 26 hospitals refused to participate in the study. Therefore, a total of 301 hospitals participated, corresponding to a response rate of 23.5%. The most frequent justification for non-participation was a very low annual number of inpatient deaths (Figure 1).

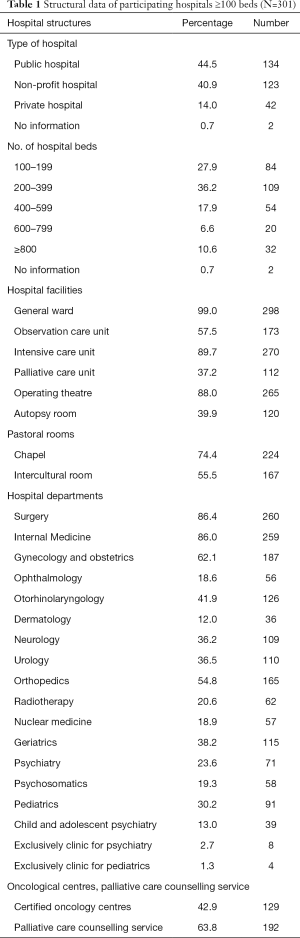

Structure of hospitals

Of the 301 participating hospitals, most were under public or non-profit ownership, and merely 14.0% [42] were private hospitals; 36.2% [109] had a size of 200 to 400 beds and 10.6% [32] offered more than 799 beds. Four percent of hospitals [12] were exclusively psychiatric or children’s hospitals, 89.7% [270] had an intensive care unit and just 37.2% [112] had a palliative care unit. Four out of ten [120] hospitals were equipped with an autopsy room. Table 1 indicates the structural data of participating hospitals.

Full table

Hospital deaths

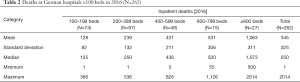

Two hundred and sixty-two out of 301 participating hospitals provided information concerning the number of inpatient deaths in 2016. The average number of deceased patients was 345 per year. The number ranged from 1 to 2,014 deaths. Table 2 shows the amount of deaths stratified by hospital size.

Full table

Prevalence of bereavement rooms

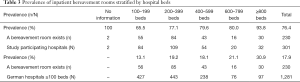

A total of 230 hospitals reported the existence of a bereavement room. Accordingly, 76.4% (230/301) of the participating hospitals provided a bereavement room. With referring to all German hospitals >100 beds, a 1-year prevalence rate of at least 17.9% (230/1,281) was determined.

The prevalence was associated with hospital size and increased with the number of hospital beds offered. The prevalence ranged from 13.1% (100–199 hospital beds) to 30.9% (≥800 hospital beds) (Table 3).

Full table

A bereavement room for deceased neonates and their grieving parents had been set up in 26 hospitals. This corresponds to a prevalence of 8.6% (26/301) for all study participating hospitals and of at least 6.8% (26/382) for all hospitals with an obstetric department in Germany. In relation to all German hospitals ≥100 beds, the 1-year prevalence rate was at least 2.0% (26/1,281).

Of the 71 hospitals without a bereavement room, 25.3% [18] never intended to establish such a room. In 40.8% [29] of the cases, the hospital management stated that they had not found adequate premises.

Structure and frequency of the use of bereavement rooms

Only 16% [37] of the 230 bereavement rooms were set up in the past 5 years. Most commonly, the rooms were 10 to 25 years old. Nearly half of them [107] were located next to an autopsy room and 31.3% [72] of the rooms were in the basement.

The bereavement rooms were often elaborately designed and in 79.1% [182] of the cases equipped with religious symbols. In less than half of the rooms [106], it was possible to let daylight fall in and only one third could be cooled by air conditioning (Table 4).

Full table

68.3% [157] of the existing bereavement rooms were used regularly and 24.8% [57] were utilized rarely.

Responsibility of bereavement rooms

One hundred and seventy-three out of 230 hospitals (75.2%) stated that one or more persons had been assigned responsibility for the bereavement room.

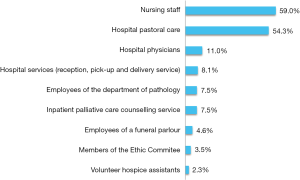

The data showed that nursing staff and hospital pastoral care were primarily responsible for taking care of deceased patients and their bereaved relatives in a farewell room. In contrast, other professions, such as hospital physicians or inpatient palliative care services, played only a minor role. In 4.6% (8/173) of these hospitals, the responsibility had been transferred to an external undertaker. Volunteer hospice assistants were only marginally involved (Figure 2).

Discussion

Summary and interpretation of findings

In our study, we determined a 1-year prevalence of bereavement rooms in hospitals with more than 99 beds of 76.4% for all study participating hospitals and of at least 17.9% for all German hospitals. A bereavement room especially for deceased neonates and their grieving parents had been set up in 6.8% of all hospitals with an obstetric department, corresponding to a prevalence rate of at least 2.0% for all hospitals ≥100 beds in Germany.

This result is remarkable as it demonstrates the existence of an inpatient bereavement room in almost every fifth German hospital with more than 99 beds in 2016. The prevalence was higher in larger hospitals than in smaller ones. In general, it should be mentioned that our calculated prevalence represents a minimum value based on a sample of 301 hospitals, representing nearly a quarter of all 1,281 German hospitals ≥100 beds. If more hospitals had participated in our study, the relative frequency would certainly have been higher.

It remains unclear why we determined such a high prevalence. Certainly, there was a response bias. For example, more than two thirds of all participating hospitals stated that a bereavement room was available. In addition, a total of 112 hospitals reported that a palliative care unit had been established, which corresponds to a high proportion of about one third of all existing palliative care units in Germany. Therefore, it can be assumed that hospitals with a well-established inpatient palliative care service were more likely to participate in our study than hospitals without this special medical support. Perhaps the term “bereavement room” had not been defined clearly enough. We defined a bereavement room as a specially designed morgue in the hospital in which family members, friends and acquaintances bid farewell to a deceased patient in a private and dignified atmosphere. In this context, it would be conceivable that study participants might have misinterpreted a regular ward room as a bereavement room. In clinical practice, a ward room in which the patient has died is often temporarily redesigned by nursing staff so that relatives can say goodbye to their loved one in a private atmosphere. After this ceremony, this room is used as a regular ward room again.

However, we revealed a substantial deficiency in the number of bereavement rooms for bereaved couples who had suffered the loss of their baby during pregnancy, at birth, or in early infancy. In just a little more than every twentieth hospital with an obstetric department, this special support was offered. In a maternity ward, it is a normal and daily routine to hear new-born babies screams. This situation could cause an additional burden for grieving parents who have just lost their baby. For this reason, orphaned parents need a shielded room offering an adequate environment and a quiet atmosphere. It is important to ensure that the facilities of bereavement rooms meet the needs of bereaved parents and their families. For example, the door should be discreetly labelled so that other parents are not necessarily aware of the room’s purpose. Attention should also be paid to how the room is decorated. Images of families and babies are entirely inappropriate and should be avoided. Proposals for the design and equipment of this room have already been worked out (14).

We analysed that the majority of bereavement rooms in German hospitals were implemented 5 to 25 years ago and only 16% had been set up in the last five years. This observation is closely related to the historical development of palliative care structures at German hospitals. In 1983, the first palliative care unit was founded at Cologne University Hospital. It took another 22 years until the hundredth palliative care unit was established. Between 2005 and 2015, there was a particularly productive phase in the development of inpatient palliative care structures. During this period the number of palliative care units tripled to over three hundred and inpatient palliative care counselling services were set up in numerous hospitals. Recently, however, this development process has somewhat slowed (15).

Nearly half of all bereavement rooms were located near an autopsy room. In our opinion, this underlines the high responsibility of employees of pathological institutes to treat corpses with respect as well as to show compassion and sympathy to grieving relatives. Although mortality is particularly high at intensive care units (ICU), a bereavement room was only present in a quarter of them. In emergency rooms (ER), this lack of bereavement rooms was even more pronounced because a bereavement room was readily available in less than 2% of ER.

Our data show that most bereavement rooms were elaborately designed and thus met high standards (16,17). The rooms were often decorated with pictures, curtains, candles and flowers to create a pleasant and dignified atmosphere. Religious symbols were also often present reflecting the spiritual character of these rooms. However, in almost a third of the cases, the bereavement room had been set up in the basement and less than half of the rooms were illuminated by natural light. Furthermore, air conditioning was available in only one third of the rooms. This fact is of practical relevance as in some cases, room cooling is necessary to prevent corpses from decaying quickly.

The mere existence of a bereavement room does not automatically imply an improvement because professional care of the deceased and their family members in hospital requires a motivated and engaged staff as well as clearly defined responsibilities. We found that in two-thirds of all hospitals with a bereavement room, the responsibility for this room had fortunately been regulated and was mainly assigned to hospital pastoral care and nursing staff. It is not surprising that hospital pastoral care workers are particularly involved in this task, since care and accompaniment of dying patients and their bereaved relatives is an essential part of their job. The nursing staff had also been given responsibility. It was astonishing to find out that nurses were slightly more often involved than spiritual care professionals. This is noteworthy as the workload of nurses has been extremely high for years and caring for deceased patients and their relatives is an additional burden. Providing appropriate support and care for end-of-life patients and their relatives is also a major concern and a daily responsibility for physicians. In addition, grief counselling should be part of their medical practice. However, we found that in only 11% of all hospitals with a bereavement room, a physician had been assigned to organize and manage this room. We also determined that in 4.6% of bereavement rooms the responsibility had been transferred to an external undertaker. Unfortunately, volunteer hospice assistants were only marginally involved (2.3%). This observation is particularly worth mentioning as the political legislator in Germany passed a new law in 2015 to strengthen palliative and hospice care which makes it possible that hospitals can entrust outpatient hospice services with the care of deceased hospital patients (18). Our data show that this legal option has not yet been implemented in everyday clinical practice.

So far there have been hardly any studies on the quality of care for dying patients and their relatives at German hospitals. George et al. conducted the largest study to date on this topic in 2013 at 212 German hospitals (19). A total of 1,350 hospital employees took part in this survey, 81% of whom were nurses and 19% were physicians. Dealing with the deceased at the workplace was described by 71% of the participants as very or rather humane, but 29% did not think so. The spatial conditions of the place of death were estimated as inadequate by 35% of nurses and physicians, 20% considered them as sufficient, 25% as acceptable, 14% as good and only 3% as very good. Dealing professionally with dying patients and grieving relatives was described by 38% as poor and by 17% as sufficient. Only 25% of the respondents stated that they could always or regularly take time to care for dying patients and 46% of nursing staff reported that usually there were not enough nurses available to accompany dying patients. Bussmann et al. carried out a cross-sectional survey in 2008/2009 in the Federal State of Rhineland-Palatinate (Germany) to get a representative picture of the experiences of bereaved family members concerning the end-of-life (EOL) care of their deceased relative in a general hospital setting. In this context, family members described structural inpatient deficiencies, such as a lack of availability of qualified health care professionals who have time to focus on the patients’ problems and concerns. Furthermore, they expressed their wish for holistic health care beyond purely medical treatment (20).

These study results reveal that there was a substantial deficit in end-of-life care at German hospitals in the past. In the meantime, the education and training of nurses and physicians has improved considerably. Dealing with death and dying is now an integral part of the education curricula of both professions. For example, the regulation on licensing doctors was amended. This amendment requires that all medical students now receive mandatory instruction in palliative medicine in order to pass their state examination.

This enhanced teaching of nurses and doctors is intended to reduce uncertainties and fears in dealing with dying patients and their families and to improve communication with them.

Which steps must be taken to make hospitals a good place for dying patients and bereaved relatives? In Ireland, an exemplary approach has been in place for a few years through a government program that designs hospitals in such a way that they can be designated as Hospice Friendly Hospitals (21). An improvement process is proposed in which the hospital operators and of course their employees are advised and supported in order to guarantee better care of dying patients. In Germany, such a government program does not exist yet. In 2010 the “Charter for the Care of the Critically Ill and the Dying in Germany” was launched (22). In its five guiding principles, this document highlights the challenges facing social policy, lists the requirements to be met by care structures and at all levels of training, enumerates the development perspectives for research, and compares the standard of palliative care in Germany with that found in other European countries. More than 620 institutions have since signed the charter. The document is being used as a basis for preliminary work on the development of a national palliative care strategy.

Limitation of the study

Our study has strengths and limitations. This study is the first investigation on the prevalence of bereavement rooms at German hospitals. To our knowledge, there are no international studies on this topic either. We conducted a cross-sectional study because this design allows an overview of the existing health care structures. A cross-sectional study design is very suitable for hypothesis generation, but it does not allow any causal conclusions to be drawn.

For content and methodological reasons, we limited our focus to hospitals with more than 99 beds. Accordingly, our findings are only applicable for these medical centres of this size. In our study, the response rate was just 23.5%, which is low but not uncommon for observational studies. Our observed proportion of hospitals with more than 800 beds was slightly higher and the fraction of hospitals with 100–199 beds slightly lower compared to all German hospitals. Therefore, our results are not representative.

We contacted the medical directors of the hospitals asking them to participate in the study. It can be assumed that they delegated the completion of our questionnaire to other hospital staff. Therefore, we were unable to find out which hospital employees filled in our questionnaire and what level of knowledge he or she had on this subject. That is the reason why we must assume that the quality and reliability of the responses varied greatly.

Conclusions

In this observational study, we determined a 1-year prevalence rate of at least 17.9% for the existence of a bereavement room at German hospitals ≥100 beds. Thus, almost every fifth hospital had such a special room. Concerning the participating hospitals of the study, we were able to calculate a prevalence of inpatient bereavement rooms of 76.4%.

Overall, the low absolute number of bereavement rooms can be seen as an indicator that still more attention should be paid to post-death care of deceased patients and bereaved relatives in hospitals and that inpatient palliative care structures should be strengthened.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported with regard of contents by the German Association for Palliative Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin). We also acknowledge support by the DFG Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was submitted to the Ethics Commission of the Ruhr-University Bochum and obtained ethics approval (reference number 17-6067).

References

- German Hospice and Palliative Care Association (Deutscher Hospiz- und PalliativVerband e. V.). Knowledge and attitudes of people in Germany towards dying - Results of a representative population survey from 2012 and 2017. Available online: https://www.dhpv.de/tl_files/public/Aktuelles/presseerklaerungen/3_ZentraleErgebnisse_DHPVBevoelkerungsbefragung_06102017.pdf

- Gomes B, Higginson IJ, Calanzani N. Preferences for place of death if faced with advanced cancer: a population survey in England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2006-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Gysels M, et al. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cohen J, Bilsen J, Addington-Hall J. Population-based study of dying in hospital in six European countries. Palliat Med 2008;22:702-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National End of Life Care Intelligence Network. Variations in Place of Death in England. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/end-of-life-care-profiles-july-2019-data-update

- Dasch B, Blum K, Gude P, et al. Place of death: trends over the course of a decade - a population based study of death certificates from the years 2001 and 2011. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015;112:496-504. [PubMed]

- Wilson DM, Truman CD, Thomas R. The rapidly changing location of death in Canada, 1994-2004. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1752-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in Inpatient Hospital Deaths: National Hospital Discharge Survey, 2000-2010. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db118.htm.

- Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Statistisches Bundesamt). Deaths in Germany (2016). Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/Tabellen/gestorbene_anzahl.html

- Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Statistisches Bundesamt) (2018). Health - Basic data of hospitals (2016). Available online: https://www.destatis.de/GPStatistik/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEHeft_derivate_00036180/2120611167004_Korr10082018.pdf

- Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, et al. Handbook of Bereavement Research: Consequences, Coping, and Care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2001.

- Mowll J, Lobb EA, Waering M. The transformative meanings of viewing or not viewing the body after sudden death. Death Stud 2016;40:46-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chapelle A, Ziebland S. Viewing the body after bereavement due to traumatic death: quantitative study in the UK. BMJ 2010;30:c2032. [Crossref]

- Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society (Sands), UK. Sands position statement - Bereavement care rooms and bereavement suites. Available online: https://www.sands.org.uk/sites/default/files/Position%20statement%20Bereavement%20rooms%20and%20bereavement%20suites.pdf

- The German Association for Palliative Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin). Hospice and palliative care at a glance: Who offers what where? Available online: https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/neuigkeiten/informationen-fuer-patienten-und-angehoerige.html

- Department of Health and Social Care, UK. When a Patient Dies - Advice on Developing Bereavement Services in the NHS. Available online: http://www.hscbereavementnetwork.hscni.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/When-a-patient-dies.-Advice-on-Developing-Bereavement-Services-in-the-NHS-October-2005.pdf

- The Irish Hospice Foundation, Ireland. Design and Dignity. Guidelines for Hospital Emergency Departments Bereavement Suites. Available online: http://hospicefoundation.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Design-Dignity-Guidelines-Emergency-Departments.pdf

- Federal Ministry of Health, Germany (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit). The Law to Improve Hospice and Palliative Care in Germany (Hospiz- und Palliativgesetz). Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/service/begriffe-von-a-z/h/hospiz-und-palliativgesetz.html

- George W, Dommer E, Szymczak V. Dying in Hospital. Psychosozial-Verlag, Gießen (Germany), 2013.

- Bussmann S, Muders P, Zahrt-Omar CA, et al. Improving end-of-life care in hospitals: a qualitative analysis of bereaved families’ experiences and suggestions. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:44-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Irish Hospice Foundation, Ireland. Hospice friendly hospitals program. Available online: https://hospicefoundation.ie/healthcare-programmes/hospice-friendly-hospitals/

- The German Association for Palliative Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin). Charter for the Care of the critically Ill and the Dying in Germany. Available online: https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/projekte/charta.html