Phenomenology of agony: a qualitative study about the experience of agony phenomenon in relatives of dying patients

Introduction

The term agony, deriving from the Greek ἀγωνία that means “fight”, defines the last moments of the living organism’s existence before the encounter with death, and its phenomenology is still to be explored. One of the most problematic issues related to agony is its length. In fact, a typical question asked by patients’ relatives is how long the agony will last. The traditional cultures tended to cope with agony and death by using a framework which had been passed on through the generations to approach these issues functionally, consisted in a series of rituals, body handling, traditional songs and foods as emotional support, and appropriate management of the feeling of timelessness experienced by the dying person. In Western culture this difficulty increases due to the outsourcing of death to the hospitals and the social censorship surrounding this taboo topic (1,2). Despite being a critical moment for caregivers, studies on this phase are still scarce. This research is trying to respond to a growing interest in the attitudes towards the dying process (3) and towards the end-of-life phenomena (4-7) The present study considers this specific problem from an interdisciplinary perspective (2,8-16). The original approach is studying the phenomena surrounding agony and almost linking it to direct clinical observation. The clinical work in a hospice has allowed us to observe some signals which can indicate not only the beginning of agony, but also how long it will last. Within a culture that “denies and defies death” (17), having the elements to read the situation contributes to the construction of a meaningful context and support, thus allowing the family to cope with death-related fear and stress (17) and help them to achieve the ‘important task of being with the dying’ (6). One possible model to read the signs of agony is based on the Tibetan book of Death (18). The observations made on the body at the patients’ deathbed as well as medical studies seem to describe death signs likewise. There are some detailed studies on this topic (19-24), but they are not connected to death time predictability. By observing dying people and comparing their symptoms with the Tibetan book descriptions, we could recognise the ones which are specifically related to agony duration.

Methods

The research

Our study is based on the importance of sharing with patients’ relatives this simple model, based on some information from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, to help them observe the changes in the dying body and to have a hypothesis about the length of the patient’s lifespan on the deathbed. Helping the relatives contributes to support the dying person. In order to make the agony recognizable, we have explained to them three different medical and directly observable parameters of imminent death: breathing, wrist consistency and interruption of diuresis. The first one is the transition from nasal breathing to mouth breathing (estimated survival: no more than 3 weeks). The evolution consists in a progressive shift from a diaphragmatic-abdominal to chest breathing, in which only the breastbone is raised, which is indicative of a markedly worsening clinical situation (estimated survival: no more than 1 week). The second is the wrist parameter. The relatives were invited to test and perceive the different strength and elasticity of the skin, as well as notice the “emptiness” which indicates that the vital energy is gradually leaving the body. This observable parameter changes consistently with the upward movement of the breath. The natural path of body changing in agonic states appears as a slow movement of the breath from toes to head. “We come into the world head first, and we leave it head last” (ancient taoist proverb). The third is the interruption of diuresis (it is associated to death within a few hours). The three parameters are communicated to relatives in a specific support model called “human protocol” (25). The aim of this research was to verify if the information about the observable signs had been useful for them to reconstruct a framework of meaning around their experience. The study had conducted in October 2017 with relatives of patients who died in hospice between April and August 2017.

Aims and strategy

We utilized the indication of the three parameters helping relatives to have some reference points during the last moment of their loved one’s life. In the other hand, this approach could permit some functional behaviours: leaving their beloveds to go, and having the strength to stay and taking the right time to say good bye to them. In the post-exitus, we wanted to analyse this experience with participants, involving them in the recognition of the factors and the description of their grief work after this supported experience.

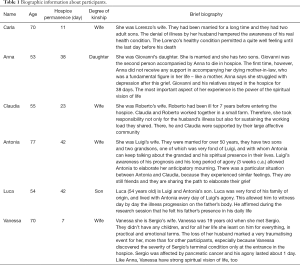

Participants (Table 1)

Full table

The group of participants is a purposive and homogeneous sample composed by hospice patient’s relatives (26). The selection had oriented by the aim of investigating the agony phenomenon in a homogeneous group. The inclusive criteria were: having received support from the hospice psychologist at least two weeks before the exitus; being interested in participating to the research; giving the consent to be contacted again two months after the exitus for an interview in the hospice. Six participants were selected (four wives, one son, and one daughter). The average duration of these patients’ hospitalization was 24.2 days (range, 7–42 days; SD =15.64).

Methodology

We have used the thematic analysis, which is a specific model to qualitative research developed on the basis of the Grounded Theory Methodology (27). Our research has combined this methodology with Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. GTM and IPA are systematic inductive methodologies which involve the use of qualitative data in terms of their principal concepts or themes, by detecting conceptualizing indicators of significant phenomena, which may be cognised through a process of interpretative and hermeneutic work. Therefore, both GTM and IPA look at the active role of persons, who may offer profound and rich data, to understand psychological and existential situations (28,29). The dialogue has followed a semi-structured pattern of issues, developed through IPA. The estimated length of each interview was about 1 hour. We asked the participants to share with us the relevant aspects of their experience with their terminally ill relative. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, in order to obtain the corpora. The analysis of the textual data was developed according to both primary and secondary descriptors, which became clear only at the end of the analysis. Moreover, before writing the report, the analysis of the textual data followed the strategies of the thematic-networks, which are the skeleton of the main themes developed in the narrations. Thematic analysis was performed with Atlas.ti 7, which is a software that allows to identify the networks of meaning.

Results

The context and the hospice choice

Our results show that all the participants considered the choice of the hospice as essential for their relatives’ well-being.

Participants believed pain management to be extremely important, also considering the hospice as a good choice due to the fact that patients had a 24/7 palliative care.

“I’ve had cousins who screamed out of pain. I have never seen Roberto in such a state..only some grimaces.”; “rather than suffering, it’s better for him to be gently accompanied” [Claudia];

“I’ve seen that there was no pain. I know that they gave him morphine, I don’t know how many times during the day, but at least he didn’t suffer, I think.” [Vanessa];

“when they started to give him morphine, I thought that my mother died within 15 days of taking morphine..he took morphine and he died too. Morphine weakens the body but it relieves the pain” [Carla].

In these extracts, patients’ wives affirmed to have been relieved by the awareness that their husbands did not suffer thanks to drug administration. However, they were also uncertain about the therapy efficacy because of previous experiences (Carla) or of the difficulty of evaluating the patients’ actual degree of suffering. In fact, the patients were not usually able to communicate their pain because of profound sedation. We can assume that drugs guaranteed the elimination of physical pain, giving relief to patients, but that they could not remove cognitive, emotional and sensorial perceptions. In addition to the benefits to the patients, the satisfaction of family members’ needs also emerged. In fact, the admission in the hospice opened up the possibility of relieving the load of caregiving for those who took care of the patients at home.

“It was a great support, because you get to live a certain moment during the disease when you realize that you cannot make it at home alone, for many reasons: maybe because the condition can get worse, maybe you lose the strength, because you’re not able to go on and face this experience, also psychologically. You need someone to help you” [Anna].

The same participant emphasised that being able to receive constant assistance, in a different place from home, allowed her to dedicate herself completely to her loved one during the visits.

“Here, with the help of professionals, you are truly at the disposition of your loved one. You can give him all your time, which can be an entire day, half a day, two hours and do it in the best way” [Anna].

The relatives had an ambivalent perception concerning the hospice. In fact, some of them represent the hospice as a mirror of their terrible situation.

“It couldn’t be used” [Anna], because

“it’s a place of death” [Carla].

On the one hand, they perceived the hospice as a functional and equipped structure, where there was staff availability and expertise. On the other hand, they experienced a continuous inner struggle between the perceptions of hospitality and the pain of imminent loss. Someone actually felt at home. Others attributed to the hospice a different connotation. They emphasised the feeling of sadness connected to the place, which, however, did not compromise its hospitality.

“Sad, sad, sad. Here you can see the passage of death and it is very sad [..]. Although it is very welcoming” [Carla].

A participant expressed the perception of maximum hospitality in this way:

“It seems like home here” and added: “I have never been here before my experience with Roberto, but I came back so many times..it just seems..it was our home for a month and a friendship with Antonia was also born here” [Claudia].

When focusing on the patients’ perceptions of the choice of hospitalization, some relevant information concerned the feeling of safety and peacefulness. They probably derived from the timeliness of the assistance interventions and from the flexibility of visiting hours, which allowed them to remain constantly beside the patient, sometimes even during the night.

“He never asked to come home, he felt safe here” [Claudia].

Another view was that the corridor of the hospice looked like “the arm of death”.

“It’s a terrible place. It was a terrible experience. Walking along the corridor and passing one room after another, I always thought that this was a prison and that there was a person condemned to death in every room” [Vanessa].

In order to better understand these two different experiences, it is useful to consider that Claudia’s husband had been ill for years. They were also part of an extended family and social system. By contrast, for Vanessa her husband was her only point of reference. She learnt about his terminal state only at the time of entry into the structure.

“Even while they were transferring Sergio from Trecenta to here, I called my doctor to know something about my husband’s health. He asked me if Sergio was a terminal patient. And of all people he asked me?! You are the one who should tell me, doctor! I found myself here alone, without anyone telling me the truth, I had to figure it out on my own” [Vanessa].

Unlike Claudia, Vanessa had to cope with this terrible truth all at once. For Claudia, it probably marked only the beginning. Luca described the hospice in the same way as Vanessa did, but he talked about it with humour. Humour can be a coping mechanism to deal with a painful situation in an ironic way (30).

“When I told my mother that we were coming here, she was ready. Now it’s a little shocking, but we’re here, in this place, the place of crime” [Luca].

A sort of coexistence of an ambivalent experience is also possible, connected to the particular time of agony, when everybody experiments a break of their grounding reality.

Phenomenology of agony. If the world were fully predictable, life would be without sense. Considering this, the first perception of agony deals with its length:

“He was so attached to life that he held out beyond medical predictions” [Claudia].

The change of the body during the agony is a relevant point of reference for the relatives because it signs the steps towards the death of their beloved one. For example, during their permanence in hospice, a patient and his relatives noticed the swelling of his body and considerable weight loss:

“Here are my swollen legs, here I am swollen”, he tells me, “but, here, I look as person in a concentration camp..” [indicating the area of the sternum and the arms] he was very thin, my son realized that his father did not have buttocks anymore. When my son accompanied him to the bathroom, he told me “look at my dad, he does not have buttocks anymore, I was shocked to see him, he was bloated..” [Carla].

Moreover, other participants also noticed the body changes. The loss of weight and low level of energy usually draws attention. In the days preceding death, relatives have to deal with a body image of the beloved that is different from the one they witnessed while he/she was healthy.

“You could see it from the smile, it wasn’t Luigi’s smile anymore” [Antonia].

In this quotation, the recall of the smile could be associated to the loss of the patient’s identity that, for the wife, was no longer the same.

“He wasn’t himself anymore. I asked to take some pictures here when he was dead and he had changed a lot. So much. Very, very much..” [Antonia].

The experience of Mr Giovanni’s daughter focuses on the loss of energy that collided with the memory she had of her father before the illness.

“Physically? Well, he physically changed because his body transformed, from a man that could smash the world..he had strength, energy..he was tireless..then I saw him getting more tired every day, he lacked appetite more and more..he struggled resting” [Anna].

The seeming closure of the patient regarding the external world characterises, in most of the cases, the last days before death. The patient is perceived as exhausted and weak, along with the loss of any mean for verbal communication, and this is engraved in the relatives’ memory.

“At the end he couldn’t talk anymore” [Anna]; “he didn’t speak anymore” [Claudia]; “the last moment in which we had a word was 4 days before his death” [Anna].

The “human protocol” model (25) describes the phenomenology of agony as an individual experience characterised by three main phases. Each person can go through these phases with a unique path, in terms of length, perceptions and feelings. At the end of agony, the dying people became one with their breath and the contact with them consists in greeting, holding hands.

In most cases, the signs of impending death appear gradually and intensify. This gives the family a chance to become aware of imminent death and face the reality from which it is no longer possible to escape.

“As time passes you notice the aggravation of the situation, so you realize” [Anna].

Awareness permits to define, albeit with difficulty (note the pause before the words: “..of death”), agony as a path that inevitably leads to the end of life.

“This path helps us since we know that it is difficult, in short..of death” [Anna].

Instead, those who expected to witness a sudden death, were surprised to see a gradual process from life to death. The concept of “turning off” after having been “consumed” appeared clear in the following narrative:

“Just so, I thought one thing..different and unfortunately it is consumed as you saw yourself, just as the candle, the candle” [Luca]; “It's really off, it did not even have a little [gasp], in the idea that I had he should take at least a breath and then you can no longer breathe and you block while he died slowly.” [Luca].

There are some (rare) cases in which the entry into the agonic phase is not progressive but sudden. As told by Carla, the husband, despite the physical deterioration until the day before his death, was seated reading the newspaper just as he had always done.

“The day before..he was sitting on those parlours in front of the rooms saying that he felt good, that he had read the newspaper..that he was interested in the political page..” [Carla].

If the perception of normality distances the thought of death, other elements, on the other hand, are carriers of mortality silence. For example, the characteristic death rattle breath of the agony’s time, unmistakable and associated with the last hours of life. The singularity of rattle sound, causes it to be recognizable even for those who have never heard it. A participant provided a snapshot of the moment when he heard it.

“When he started with this rattle, with this noise..And I wondered how long it would last and when it would happen” [Vanessa].

“I understood it was the death rattle” [Antonia].

However, only two out of six participants spontaneously revealed this perceptual detail. It is possible, in line with studies of Wee and colleagues (31,32), that the other participants did not perceive the disturbance of this sign and consequently did not report it as a predominant feature. Not only the bodily signs, purely observable, trigger mortality silence, but also other elements. For example, the explication of the desire to die, in order not to keep living with the disease. In this regard, Antonia told, with great sadness, an episode in which her husband expressed the fear of the progression of disease, long before being admitted to hospice.

“Only once he told me ‘rather than being like that’ (still when we used to walk through the industrial area) ‘it would be better if I died’” [Antonia].

According to Terror Management Theory (TMT), the difficulty of going to the bedside emerged, putting in place mechanisms of avoidance towards the terminally ill, whose only visit is able to recall the awareness of our finitude (13,14).

“Every day they send a message ‘how is he?’ I would like to come visit him but I don’t have the courage” [Claudia].

In relation to TMT, the awareness of the taboo of death in our society emerged as well, and how this mechanism made this intrinsic process of life almost unbearable.

“Yes, very difficult, and I also think that an error of our society is that of not considering death, a serious mistake in my opinion” [Luca].

Psychological support

The recurring question of the relatives, “how long will it last?” paralyzed by the anguish of not knowing, conducted this research. The hypothesis was if the relatives could observe their beloved through ancient suggestions as well from Tibetan Book of Death, and they could recognize the progressive process until the end of the world, it should be useful. Two of them, when asked about the usefulness of the communication received, answered:

“Yes, she did well to tell me, because from that moment I started to look at the breath and the other things she had told me” [Vanessa].

“They were details that I did not know, then I was..to the indications that you gave us on breath..about the fact that maybe the bag began, the higher breath, you are never ready, but to prepare yourself..” [Claudia].

Referring again to the communication of body parameters, we could see how the lack of experience regarding dying stands out, and how those indications favoured an autonomous observation process, providing new perceptual conditions. The preparatory aspect that this point of observation allows was outlined.

“The wrist so slow, the blood pressure 60 on 40..but he survived, he seemed almost recover in health” [Luca].

Even for those who did not provided a clear feedback on the directions given, it was possible to find an implicit result of observation behaviour, and the evidence that being there at the moment of last breath could help, for example:

“I wanted to see him because I feel better to see him die than not see him..I watched him die but I couldn’t see his face because he always wore a mask..” [Antonia].

It is also likely that the participant focused her attention on her husband’s oxygen mask, in an attempt to monitor the change in the respiratory pattern indicated.

Further, it highlighted how certain details are precisely remembered, for example, the accuracy of the memories of the days before death, phrases of the nursing staff and the focus on registered physiological parameters. The phenomenon described above appears to refer to the characteristics of salience connected to the moments of birth and death, as if the present moment (11) imposed the utmost attention and the fixation of memory.

A noticeable feedback regards some suggestions on functional behaviour around the patients during the agony. The first suggestion was to use remembering happy events from the life of family:

“The tip of remembers was very useful, I never mind to show to him our photos..I did not think..conversely..He had like to see our photos more than one time..” [Claudia].

It normally happens in the first phase of agony that dying people needs a sort of review of their life, as a final balance sheet, and the role of relatives is essential. The second suggestion was about the relevance of the last greetings.

“At the end, all found the force to come at the last moment..everybody came to greet him” [Claudia].

The practice of greetings became strategic in respect with the aim of relatives to make the maximum as possible, and this can realize the condition to pass through the pain with a sufficient quality of life, and to empower their’ belonging.

“He loved so much his family, He wanted to see us together as a group, and it was possible to see that this was so important during the period of illness” [Claudia].

Finally, the practice of greeting could permit to close the unfinished business (25), and to cope differently with the grief.

“Having something as unfinished business, regretting..it must be worst. In the other hand, having had the right time to live everything with peaceful..” [Claudia].

Discussion

The three areas seem to share a pattern. In fact, there is a common implicit and active purpose to cope with the experience of dying and to ensure the well-being as much as possible for the patients and their families. The participants seemed to agree on the adequacy of the choice of hospice admission. The possibility of pain management, with palliative care, prevailed over the perception of anguish and sadness, which the hospice is usually associated with. The observation of bodily phenomena during the agonic states could play a coping role in different ways. In particular, while half of the participants reported the usefulness of the observation behaviour as evident, the other half did not. A hypothesis for the latter group’s report may be due to a self-defence denial strategy (9,33,34) in dealing with dangerous information, or to the constant closeness to the dear one. The progressive loss of energy and the patient’s inability to communicate allowed the relatives to become aware of the imminent death of their loved one, and the conspiracy of silence is broken. The ceasing of conversation seems to be a loud sign of the imminence of death, just like terminal rattle. A sign that remained vivid in the relatives’ memory is the respiration of their dear one during the last agonic state. The communication of the signs of agony aims at dealing with the lack of practical experience regarding the process of dying. The grounding experience in the path of the terminally ill was connected to different periods in the illness, in which the symptomatology passed from stabilization periods to vertical collapse. The alternation could be a reason to maintain a high level of hope to resolve negative prognosis. In addition, another factor is the mistaken time prevision in medical prognosis. Given that the interviews were retrospective, it is also possible that the grieving process could have interfered with the relatives’ representation, even if information about the provision of care and assistance appeared to be more reliable (35,36). The psychological support played a pivotal role in supporting the experience of agony alongside the dear one. The support aimed at providing relatives with the appropriate tools to cope with the last greetings, the closure of unfinished business, and the perception of having done everything that was possible for the loved one. The effects of the psychological support can be noticed in all the three areas of response. In this research, the aim was to investigate the phenomenon of agony through the experiences of family members, in order to obtain feedback on the potential utility of the proposed specific support in the clinical field. This support was customised in response to the needs of family members who, since they belonged to a socio-cultural context that scotomises death, found themselves lost and completely unprepared. Orienting relatives in the path of accompanying their loved ones in their last moments offers them the chance to satisfy their main need, which is synthesised in the question: “How long will it last?” The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the studies on the signs of impending death (24) and clinical practice allow us to restore, through the therapeutic alliance, a function of orientation of the culturally lost experience. These results encourage further research on the model of specific psychological support called “human protocol” (25). In this research, we can see how important it is to have some point of reference to contain emotional pain and to cope with this trial of life. Standing at the patients’ deathbed during agony requires competences in order to share a system of observation of visible parameters, which permits to recognize and to answer the duration question. The most important result is the possibility for relatives to give their last greetings. Being aware of the progression with which the body changes happen during agony seems to engage a locus of control experience of the situation, thus leading to the sensation of having put all possible effort into it (17). The use of a “human protocol” becomes crucial for the treatment intervention aimed at the specific need of the present moment. A structured support allowed for the patient not to be alone and for the family to understand when it was time to say goodbye to him. The clinical aim found its highest enforcement in these results because they show the relevance of an integrative support, merging medical, psychological and cultural approaches. Although the results are still partial due to intervening variables such as the method of investigation or the selection criteria for the participants, they represent a first attempt to analyse the time window of agony that has not been investigated so far.

It is possible, however, that the semi-structured interviewing modality used to collect the experiences did not allow some themes to emerge. Considering this, it would be interesting to explore the experiences of agony in a focus group, or to use a non-structured interview, but also through the combination of multiple survey methods (non-structured interview, check-list and questionnaire). Another variable to be considered is the timing. In fact, it may be useful to ask relatives for feedback during the period of stay in hospice, and not only a few months after the death of their loved one (period in which the grieving process may interfere). Furthermore, the investigation on the phenomenon of agony could be extended not only to other similar groups, but also to the experiences of those who face the accompaniment to death in a home environment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of the hospice where this study took place (Hospice “Casa del Vento Rosa”- Lendinara, Italy), the patients and their family members who accompanied them to the end of their life. We would also like to thank the University of Padua, which allowed us to carry out this research.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study follows the APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by institutional ethics board of “Casa Albergo per Anziani”- Lendinara (No. 4484). Participants were informed about the aims and procedures of the study, in order to make sure the participation was voluntary. The confidentiality of their responses was guaranteed. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

- Solomon S, Testoni I, Bianco S. Clash of civilizations? Terror Management Theory and the role of the ontological representations of death in contemporary global crisis. TPM Test Psychom Methodol Appl Psychol 2017;24:379-98.

- Testoni I. Psicologia del lutto e del morire: dal lavoro clinico alla death education. Psicoterapia e Scienze Umane 2016;50:229-52. [Crossref]

- Groebe B, Strupp J, Eisenmann Y, et al. Measuring attitudes towards the dying process: A systematic review of tools. Palliat Med 2018;32:815-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Betty LS. Are they hallucinations or are they real? The spirituality of deathbed and near-death visions. Omega 2006;53:37-49. [Crossref]

- Fenwick P, Lovelace H, Brayne S. Comfort for the dying: five year retrospective and one year prospective studies of end of life experiences. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010;51:173-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hockley J. Intimations of Dying: A visible and invisible process. J Palliat Care 2015;31:166-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Claxton-Oldfield S, Dunnett A. Hospice palliative care volunteers’ experiences with unusual end-of-life phenomena. Omega 2018;77:3-14. [Crossref]

- Grof S. The ultimate journey: consciousness and the Mystery of Death. Santa Cruz, California: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), 2006.

- Kübler-Ross E. On death and dying. London: Routledge, 1973.

- Rando TA. The increasing prevalence of complicated mourning: The onslaught is just beginning. Omega 1993;26:43-59. [Crossref]

- Stern DN. The present moment in psychotherapy and everyday life. New York: WW Norton & Co, 2004.

- Testoni I, Francescon E, De Leo D, et al. Forgiveness and Blame Among Suicide Survivors: A Qualitative Analysis on Reports of 4-Year Self-Help-Group Meetings. Community Ment Health J 2019;55:360-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Testoni I, Falletti S, Visintin EP, et al. Il volontariato nelle cure palliative: Religiosità, rappresentazioni esplicite della morte e implicite di Dio tra deumanizzazione e burnout. Psicologia della Salute 2016;2:27-42. [Crossref]

- Bauman Z. The individualized society. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2001.

- Becker E. The Denial of Death. New York: Free Press, 1973.

- Gorer G. The pornography of death. Encounter 1955;5:49-52.

- Bourgeois S, Johnson A. Preparing for dying: Meaningful practices in palliative care. Omega 2004;49:99-107. [Crossref]

- Coleman G, Jinpa T. editors. The Tibetan Book of the Dead: First Complete Translation. London: Penguin, 2008.

- Mercadamte S. Death rattle: critical review and research agenda. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:571-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mercadante S. Cure palliative e di supporto in oncologia. Torino: Edizioni Minerva Medica, 2016.

- Perkin RM, Resnik DB. The agony of agonal respiration: is the last gasp necessary? J Med Ethics 2002;28:164-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lieberson AD. Treatment of pain and suffering in the terminally ill. Precious Legacy.1999. Available online: http://preciouslegacy.com/

- Hui D, Dos Santos R, Chisholm G, et al. Bedside clinical signs associated with impending death in patients with advanced cancer: preliminary findings of a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Cancer 2015;121:960-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Dos Santos R, Chisholm G, et al. Clinical signs of impending death in cancer patients. Oncologist 2014;19:681-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galantin L. Madre senza Tempo. Linee guida per l’accompagnamento ai morenti. Editrice Dapero, 2019.

- Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. New York: Sage, 2003.

- Corbin JM, Strauss AM. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. 3rd ed. New York: Sage, 2008.

- Testoni I, Ghellar T, Rodelli M, et al. Representations of death among Italian vegetarians: An ethnographic research on environment, disgust and transcendence. Eur J Psychol 2017;13:378-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Testoni I, Russotto S, Zamperini A, et al. Addiction and religiosity in facing suicide: A qualitative study on meaning of life and death among homeless people. Mental Illness 2018;10:7420. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thorson JA. A funny thing happened on the way to the morgue: Some thoughts on humor and death, and a taxonomy of the humor associated with death. Death Studies 1985;9:201-16. [Crossref]

- Wee BL, Coleman PG, Hillier R, et al. The sound of death rattle I: Are relatives distressed by hearing this sound? Palliat Med 2006;20:171-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wee BL, Coleman PG, Hillier R, et al. The sound of death rattle II: how do relatives interpret the sound? Palliat Med 2006;20:177-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McWilliams N. Psychoanalytic Diagnosis. New York: The Guilford Press, 1994.

- Chandra PS, Desai G. Denial as an experiential phenomenon in serious illness. Indian J Palliat Care 2007;13:8. [Crossref]

- Higginson I, Priest P, McCarthy M. Are bereaved family members a valid proxy for a patient's assessment of dying? Soc Sci Med 1994;38:553-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hinton J. How reliable are relatives' retrospective reports of terminal illness? Patients' and relatives' accounts compared. Soc Sci Med 1996;43:1229-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]