Palliative care and Parkinson’s disease: outpatient needs and models of care over the disease trajectory

Introduction

Disease burden is substantial for those with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Uncontrolled symptoms, care partner burden, and prolonged anticipatory grief are common over the course of the condition with a negative impact on quality of life (1-5). Additionally, given the long disease trajectory and changing symptoms over time, many patients have unpredictable periods of high needs, leading to increased emotional and financial strain on patients and families (6).

Current care models for PD and medicine more broadly are often disease-centered. Patients are the recipients of care, frequently playing a passive role in decisions about their condition. The physician and care team set visit priorities, and while individual symptoms may be identified and managed, limited patient and family input results in providers having a poor understanding of the most impactful symptoms or overall disease burden (7). Patients and families may be unaware of the multitude of symptoms that can be associated with PD, and care often focuses on motor symptom management with non-motor symptoms and the psychological strain of the disease frequently under-recognized (8-11). Additionally, the disease-centered model of care is frequently reactive, treating symptoms and needs as they arise rather than anticipating symptoms and planning for next steps.

In contrast, a palliative approach to care is person-centered. Palliative care centers around the relief of suffering for patients and families affected by serious illnesses and helping them find joy (6). Rather than focusing on individual symptoms or “deficits” associated with the disease, “total pain” is considered, including efforts to help patients flourish (12,13). Quality of life is prioritized, and the clinician works to understand the patient and family’s care preferences to proactively anticipate changes to not only mitigate burden but help patients and families find meaning and purpose. Clinicians also conduct conversations to allow patients to understand the disease course, consider priorities, and plan for the future. There is a clear role for palliative care in at the end-of-life in patients with PD; however, the disease trajectory is non-linear and identifying “end-stage PD” is challenging. In the United States (US), the Medicare hospice benefit is focused on end-of-life care, but eligibility criteria are poor predictors of mortality in PD and are restrictive, limiting enrollment (14,15). While other countries are not governed by hospice criteria, many have their own barriers to access high quality end-of-life care, such as availability of specialists and reliable payment mechanisms. There is now rising recognition of the role of a more comprehensive palliative approach to care throughout the course of the illness (5,6). However, there are limited data defining the optimal methods for the implementation of palliative care in PD in the outpatient setting.

Here, we will describe the palliative approach to care for those with PD. We aim to (I) demonstrate the need for palliative, person-centered care in PD by reviewing existing literature on symptom and overall disease burden; (II) describe existing models for the delivery of outpatient palliative care for those with PD; and (III) identify gaps in our understanding of the use of outpatient palliative care in PD.

Disease burden

Symptom burden

Both motor (tremor, slowness, walking changes) and non-motor symptoms (pain, psychiatric disease, sleep disturbances) are common over the course of PD and contribute toward overall disease burden (2,16,17). Individuals with PD have similar degrees of symptom burden to those with advanced cancer and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) with a negative impact on quality of life (4,18). While symptoms accumulate over the course of PD, motor and non-motor symptoms can escalate and have a negative impact on quality of life at any time over the disease course. Unfortunately, many symptoms remain unrecognized and under-treated with an estimated 50% of neuropsychiatric and other non-motor symptoms undiagnosed in those with PD, despite their high prevalence (8). In a recent needs assessment of individuals with Hoehn and Yahr stage II–V PD, we identified substantial symptom burden with respondents endorsing an average of around five uncontrolled symptoms. Particularly among those with Hoehn and Yahr stage II and III disease, uncontrolled non-motor symptoms including depression, confusion, and speech changes were significantly associated with poor quality of life (19). A palliative, person-centered approach to care may allow a more comprehensive assessment and the formulation of a care plan more responsive to the true needs of patients and families (9,20,21).

Beyond symptom burden

Beyond the substantial symptom burden associated with the disease, periods of increasing psychosocial and spiritual needs punctuate the entire course of PD and have similar negative impacts on quality of life (22). There is a substantial emotional impact with many patients describing trauma, sadness, or anger at the time of diagnosis; additionally, prolonged anticipatory grief accompanies the disease with patients and care partners concerned about what the future may hold (4,23). Changes in social roles are also common and present substantial challenges in coping with the diagnosis. Increasing physical disability can result in decreased ability to work and increased reliance on others. Additionally, evolving challenges with communication due to hypophonia, apathy, or cognitive impairment further limit social interactions and can result in increasing isolation among those with the disease (24-26).

Beyond patient needs, care partners of those with PD also have substantial burden from the time of disease onset. Care partners have significantly higher rates of depression and lower health-related quality of life compared to the general population (27). While care partner burden is not associated with disease duration, it is independently associated with increasing patient disease severity and disability (28). There is also increasing recognition that the financial toll associated with disease can have significant impact on overall well-being (29). Should a palliative approach to care be considered, services to address care partner needs and burden are also necessary throughout the course of the disease.

Models of outpatient palliative care

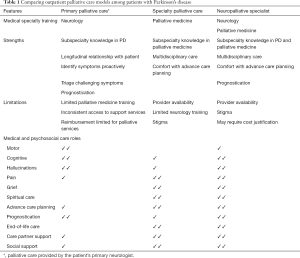

At least three models exist to implement and integrate a palliative approach in the outpatient management of patients with PD. Each differs based on the training and focus of the provider. The first involves palliative care specialists either in consultation or integrated into a multidisciplinary PD clinic; the second involves neurologists who try to cover all aspects of palliative care (primary palliative care) within their own practice; and the third is the emerging subspecialty of neuropalliative care with providers who have expertise and formal training in both neurology and palliative medicine. Key features, strengths, weaknesses, and roles of each model are described here and summarized in Table 1.

Full table

Consultative model—specialty palliative care

In this model, a medical provider with subspecialty training in palliative medicine (palliative care specialist) acts as a consultant to the patient’s primary neurologist. Palliative medicine specialists most commonly provide services outside the neurology office. However, prior work has also explored the benefit of an integrated palliative medicine specialist in a multidisciplinary PD clinic (30). Similar models have been studied and shown to be beneficial among those with ALS (31). There are data to support the use of specialty palliative care to reduce disease burden among those with PD (5) and to assist patients and care partners in coping with advancing disease (32) with ongoing studies further exploring the benefits of this model (33).

The palliative care specialist assists the patient’s neurologist in managing palliative needs, including advance care planning discussions, management of challenging non-motor symptoms and complex suffering, navigating difficult disease transitions, and assessing and mitigating care partner burden (Table 1). Specialty palliative care is typically team-based with a physician leading an interdisciplinary care team (34). While there is variation, specialty palliative care teams can include physicians and advance practice providers, nurses, social workers, chaplains, pharmacists, bereavement counselors and volunteers, among others.

Despite rising evidence for specialty palliative care among those with PD, challenges to utilization of these services remain. First, access is limited. As of 2018, there was an estimated shortfall of around 2,000–5,000 palliative care specialists in the US, and the supply of new trainees in palliative medicine is only around 50–60% of the estimated need to close this gap (35). Even where palliative care is available, substantial variation in services/team makeup may exist, which may lead to disjointed care and confusion of roles. Additionally, a majority of palliative medicine specialists are not trained specifically in neurology with only 1.5% of graduates from accredited palliative care fellowships coming from a neurology training program (36-38). Finally, stigma remains around the term palliative care with many patients, care partners, and physicians associating palliative care exclusively with end-stage disease and hospice, thus limiting utilization (39,40).

Primary palliative care model

In order to address some of these concerns, palliative care principles can and should be integrated into the care provided by the patient’s treating neurologist and primary care physician, termed primary palliative care. This model is particularly relevant to allow the pragmatic application of palliative principles to those with PD more broadly given the shortage of palliative medicine specialists and the ability of neurologists to address many palliative needs among those with PD (41). In this model, a neurologist without fellowship training in palliative care applies the principles of palliative medicine to address overall disease burden and deliver person-centered care. The provider aims to identify and manage palliative care needs early (pain, fatigue, depression) and leads conversations around prognosis and goals of care from the time of disease onset, as recommended in current American Academy of Neurology quality measures and National Consensus Guidelines to expand palliative care beyond specialists (42-44). Given the proactive focus of the model, neurologists can manage many palliative needs themselves; however, it is also essential to have an appropriate triage mechanism in place in the setting of specific triggers, burdensome psychosocial stressors, or other needs requiring additional provider support. As the model matures, additional care team members (e.g., social worker, chaplain, counselor) may be integrated into a primary palliative care team to deliver on palliative care principles more seamlessly.

While this is a departure from the disease-based model of care among those with PD today, primary palliative care can be integrated into typical clinical practice. However, neurologists will require additional training in palliative medicine. Most receive limited training in palliative care during residency, and many providers feel uncomfortable initiating or leading goals of care discussions (45,46). Additionally, increasing access to counseling and social work services is likely necessary to facilitate this model. Education surrounding reimbursement for palliative services may be necessary. In the US, providers can utilize billing codes for prolonged outpatient encounters (99354 and 99355 plus an appropriate Evaluation and Management code) or codes specifically related to advance care planning (99497 and 99498) to facilitate integration of this model into practice.

Neuropalliative specialist model

The final model is an emerging hybrid specialty termed neuropalliative care (47). Neuropalliative care specialists have formal training in both neurology and palliative medicine and are particularly well equipped to manage the significant burden associated with PD and other neurological diseases. Similar to palliative medicine specialists, the neuropalliative specialist also frequently works as a member of a larger interdisciplinary palliative care team. This model offers substantial promise to manage the palliative needs of those with PD and mitigates concerns related to lack of neurological expertise among most palliative care specialists and lack of comfort with palliative medicine among neurologists. However, with only a small number of neuropalliative specialists practicing throughout the US and most being affiliated with large academic medical centers, access to these services remains limited.

Expanding the reach of palliative care

In order to enhance the delivery of a palliative approach to care among the PD population, we must consider methods to expand the reach of the models described above. Adequate neurologist and palliative medicine specialist education is an essential first step to improving and standardizing palliative care delivery among the PD population. There are efforts to increase neurology resident exposure to palliative care in their training, though as of 2009, only around half of US residency programs provided formal didactics on end-of-life care, and only 8% provided a clinical rotation (48). Reassuringly, there are other educational resources available for providers including educational programs at national medical society meetings as well as more formal didactic curricula [e.g. Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC)] (49). Katz et al. created a “Top Ten Tips…” as a resource for palliative medicine specialists caring for those with PD; this includes practical information on palliative needs, medication administration, and prognosis in PD (26). Finally, prior work outside PD found benefit from a physician-patient “communication priming intervention” to facilitate advance care planning discussions (50). Patient-physician shared decision making tools may allow better alignment of care goals and provide a method to meet patients’ palliative needs.

Beyond provider education, the physical delivery of care remains a substantial barrier to broader implementation of palliative care in those with PD. This is due to both limited provider availability and substantial mobility challenges among those with advanced disease, making travel difficult. Expert palliative nurse navigators have demonstrated benefit for enhancing palliative care delivery among rural populations, though their use has not been specifically assessed in the PD population (51). Telemedicine represents a promising option for palliative care delivery with reasonable evidence for its utility among those with PD and in the palliative care setting (52,53). Additionally, this may allow dissemination of palliative medicine or neuropalliative specialists more broadly. Mechanisms for prescribing medications, facilitating local or home-based referrals, and billing for services need to be considered further.

Gaps in knowledge

While there has been rising interest in neuropalliative care and palliative medicine for those with PD over recent years, gaps in our understanding of how and when to implement these services remain. First, while there is growing support for earlier integration of a palliative approach to care among those with PD, there are limited guidelines on how to integrate routine best practices of primary palliative care and when event-based triggers should prompt referral to specialty palliative care. Work in oncology has focused on the use of specific trigger diagnoses to prompt palliative care referral (54). This approach could be useful to identify patients in end-stage PD, though additional work to define reliable disease features heralding the end of life is clearly needed (55). The use of trigger diagnoses is likely insufficient for earlier integration of palliative care in PD given substantial variability in disease progression, symptomatology, and patient experience (56). While a number of needs assessment tools have been adapted to assess palliative needs in PD, use of these measures remains limited due to being: (I) insufficiently exhaustive to assess needs broadly; (II) excessively burdensome, making implementation challenging in clinical practice; (III) validated for monitoring changes in symptoms, but not as screening tools; or (IV) validated in only isolated healthcare models (5,57-59). Future work should consider methods to screen for palliative needs more broadly in the outpatient setting. The development and dissemination of an efficient palliative needs assessment tool that is adaptive to patient priorities, disease stage, and cognitive status could facilitate broader need identification in the office (6).

Beyond better identification of palliative needs among those with PD, evidence-based interventions for non-motor symptoms, psychological strain, and care partner burden are also lacking. Additional work to identify the best methods to treat these disease features is necessary to improve provider confidence in having a meaningful intervention to improve quality of life among patients and their loved ones (60). Future work should focus not only on pharmacologic interventions but also on methods for implementation and broader dissemination of best clinical practices. Further work to validate educational programs and novel care delivery mechanisms including and beyond those described above should also be prioritized; there are a number of ongoing efforts on this front (33).

Finally, we have an incomplete understanding of the scope and magnitude of benefit of a palliative approach to care for those with PD. While certainly beneficial for identifying and managing disease burden among patients and their care partners, there are other potential benefits as well. In oncology, for example, early outpatient palliative care is associated with reduced healthcare costs, increased goal-congruent care including dying in preferred place of death, and a mortality benefit (61). However, these outcomes have not been assessed in the PD population.

Conclusions

A palliative approach to care is a promising method to improve quality of life and reduce disease burden among those with PD and their care partners. Ongoing work remains to establish methods for optimal implementation in the outpatient setting. Still, with rising enthusiasm in the field, we will likely see substantial work to validate care models and definitively establish the benefit of this approach to care in the coming years.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Quinn N. How does Parkinson's disease affect quality of life? A comparison with quality of life in the general population. Mov Disord 2000;15:1112-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shulman LM, Taback RL, Bean J, et al. Comorbidity of the nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2001;16:507-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prakash KM, Nadkarni NV, Lye WK, et al. The impact of non-motor symptoms on the quality of life of Parkinson's disease patients: a longitudinal study. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:854-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kluger BM, Shattuck J, Berk J, et al. Defining Palliative Care Needs in Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2018;6:125-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyasaki JM, Long J, Mancini D, et al. Palliative care for advanced Parkinson disease: an interdisciplinary clinic and new scale, the ESAS-PD. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18 Suppl 3:S6-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kluger BM, Fox S, Timmons S, et al. Palliative care and Parkinson's disease: Meeting summary and recommendations for clinical research. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;37:19-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grosset KA, Grosset DG. Patient-perceived involvement and satisfaction in Parkinson's disease: effect on therapy decisions and quality of life. Mov Disord 2005;20:616-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shulman LM, Taback RL, Rabinstein AA, et al. Non-recognition of depression and other non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2002;8:193-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri KR, Yates L, Martinez-Martin P. The non-motor symptom complex of Parkinson’s disease: a comprehensive assessment is essential. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2005;5:275-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ha AD, Jankovic J. Pain in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2012;27:485-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheon SM, Ha MS, Park MJ, et al. Nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease: prevalence and awareness of patients and families. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2008;14:286-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- VanderWeele TJ, McNeely E, Koh HK. Reimagining Health-Flourishing. JAMA 2019;321:1667-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clark D. 'Total pain', disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958-1967. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:727-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown MA, Sampson EL, Jones L, et al. Prognostic indicators of 6-month mortality in elderly people with advanced dementia: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2013;27:389-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- NHPCO's Facts and Figures: Hospice care in America. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; 2017. Available online: https://39k5cm1a9u1968hg74aj3x51-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2017_Facts_Figures-2.pdf

- Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:235-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, et al. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17013. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goy ER, Carter J, Ganzini L. Neurologic disease at the end of life: caregiver descriptions of Parkinson disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Palliat Med 2008;11:548-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tarolli CG, Zimmerman GA, Auinger P, et al. The palliative needs of individuals with Parkinson disease. American Academy of Neurology 2019 Annual Meeting; Philadelphia, PA, 2019.

- Titova N, Chaudhuri KR. Palliative Care and Nonmotor Symptoms in Parkinson's Disease and Parkinsonism. Int Rev Neurobiol 2017;134:1239-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saleem TZ, Higginson IJ, Chaudhuri KR, et al. Symptom prevalence, severity and palliative care needs assessment using the Palliative Outcome Scale: a cross-sectional study of patients with Parkinson's disease and related neurological conditions. Palliat Med 2013;27:722-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiong-Rivero H, Ryan GW, Flippen C, et al. Patients' and caregivers' experiences of the impact of Parkinson's disease on health status. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2011;2011:57-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phillips LJ. Dropping the bomb: the experience of being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. Geriatr Nurs 2006;27:362-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hermanns M. The invisible and visible stigmatization of Parkinson's disease. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2013;25:563-6. [PubMed]

- Soleimani MA, Negarandeh R, Bastani F, et al. Disrupted social connectedness in people with Parkinson's disease. Br J Community Nurs 2014;19:136-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katz M, Goto Y, Kluger BM, et al. Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1507-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Martin P, Arroyo S, Rojo-Abuin JM, et al. Burden, perceived health status, and mood among caregivers of Parkinson's disease patients. Mov Disord 2008;23:1673-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Martín P, Forjaz MJ, Frades-Payo B, et al. Caregiver burden in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2007;22:924-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 2017;123:476-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Veronese S, Gallo G, Valle A, et al. Specialist palliative care improves the quality of life in advanced neurodegenerative disorders: NE-PAL, a pilot randomised controlled study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:164-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blackhall LJ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and palliative care: where we are, and the road ahead. Muscle Nerve 2012;45:311-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Badger NJ, Frizelle D, Adams D, et al. Impact of specialist palliative care on coping with Parkinson's disease: patients and carers. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018;8:180-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kluger BM, Katz M, Galifianakis N, et al. Does outpatient palliative care improve patient-centered outcomes in Parkinson's disease: Rationale, design, and implementation of a pragmatic comparative effectiveness trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2019;79:28-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crawford GB, Price SD. Team working: palliative care as a model of interdisciplinary practice. Med J Aust 2003;179:S32-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, et al. The Growing Demand for Hospice and Palliative Medicine Physicians: Will the Supply Keep Up? J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:1216-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manu E, Marks A, Berkman CS, et al. Self-perceived competence among medical residents in skills needed to care for patients with advanced dementia versus metastatic cancer. J Cancer Educ 2012;27:515-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turner-Stokes L, Sykes N, Silber E, et al. From diagnosis to death: exploring the interface between neurology, rehabilitation and palliative care in managing people with long-term neurological conditions. Clin Med (Lond) 2007;7:129-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quigley L, Salsberg E, Lupu D. A profile of new hospice and palliative medicine physicians. George Washington University Health Workforce Institute. American Association of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; 2017:11. Available online: http://aahpm.org/uploads/Profile_of_New_HPM_Physicians_2016_Executive_Summary_January_2017.pdf

- Dai YX, Chen TJ, Lin MH. Branding Palliative Care Units by Avoiding the Terms "Palliative" and "Hospice". Inquiry 2017;54:46958016686449. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez KL, Barnato AE, Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. J Palliat Med 2007;10:99-110. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Creutzfeldt CJ, Kluger B, Holloway RG. Neuropalliative Care. Springer International Publishing, 2019.

- Cheng EM, Tonn S, Swain-Eng R, et al. Quality improvement in neurology: AAN Parkinson disease quality measures: report of the Quality Measurement and Reporting Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2010;75:2021-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abbasi J. New Guidelines Aim to Expand Palliative Care Beyond Specialists. JAMA 2019;322:193-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta AK, Najjar S, May N, et al. A Needs Assessment of Palliative Care Education among the United States Adult Neurology Residency Programs. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1448-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quill TE. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients: addressing the "elephant in the room". JAMA 2000;284:2502-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Creutzfeldt CJ, Kluger B, Kelly AG, et al. Neuropalliative care: Priorities to move the field forward. Neurology 2018;91:217-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Creutzfeldt CJ, Gooley T, Walker M. Are neurology residents prepared to deal with dying patients? Arch Neurol 2009;66:1427-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- EPEC: Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care: Feinberg School of Medicine: Northwestern University 2019. Available online: https://www.bioethics.northwestern.edu/programs/epec/

- Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, et al. Effect of a Patient and Clinician Communication-Priming Intervention on Patient-Reported Goals-of-Care Discussions Between Patients With Serious Illness and Clinicians: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:930-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pesut B, Hooper B, Jacobsen M, et al. Nurse-led navigation to provide early palliative care in rural areas: a pilot study. BMC Palliat Care 2017;16:37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dorsey ER, Achey MA, Beck CA, et al. National Randomized Controlled Trial of Virtual House Calls for People with Parkinson's Disease: Interest and Barriers. Telemed J E Health 2016;22:590-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Gurp J, van Selm M, Vissers K, et al. How outpatient palliative care teleconsultation facilitates empathic patient-professional relationships: a qualitative study. PloS One 2015;10:e0124387. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levy MH, Smith T, Alvarez-Perez A, et al. Palliative care, Version 1.2014. Featured updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2014;12:1379-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang RS, Poon WS. "Triggers" for referral to neurology palliative care service. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:289-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Courtright KR, Cassel JB, Halpern SD. A Research Agenda for High-Value Palliative Care. Ann Intern Med 2018;168:71-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee MA, Prentice WM, Hildreth AJ, et al. Measuring symptom load in Idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2007;13:284-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Richfield E, Girgis A, Johnson M. Assessing palliative care in Parkinson's disease-Development of the NAT: Parkinson's Disease. Palliat Med. 2014;28.

- Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Development and validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care: the palliative care outcome scale. Palliative Care Core Audit Project Advisory Group. Qual Health Care 1999;8:219-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seppi K, Ray Chaudhuri K, Coelho M, et al. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease-an evidence-based medicine review. Mov Disord 2019;34:180-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rocque GB, Cleary JF. Palliative care reduces morbidity and mortality in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:80-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]