Specialist palliative care for Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

The role of specialist palliative care for Parkinson’s disease (PD) and related disorders, such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and multiple systems atrophy (MSA) is complex. The principles of care are similar, although the prognosis does differ: for PD the average prognosis is 15 years, but many people live much longer, in PSP the average prognosis is 8 years (1) and for MSA about 6 to 10 years (2).

PD leads to many different needs—physical and psychosocial—throughout the disease progression. The disease develops over many years and it has been suggested that there are four phases:

- Diagnosis phase:

- Medication is started and rehabilitation support provided;

- Symptoms are managed effectively;

- Patient distress lessens;

- Duration 1.6 years +/− 1.5.

- Maintenance phases:

- Function and self-care are maintained;

- Continuation of normal activities;

- Multidisciplinary team care may be needed at times;

- Duration 5.9 years +/− 4.8.

- Complex phase:

- Increased disability and complexity;

- Symptoms may be an issue;

- Complex drug management;

- Increased complications;

- Dysphagia/aspiration may occur;

- Duration 4.9 years +/− 4.4;

- Palliative care phase:

- Medication less effective;

- Other comorbidity;

- Symptom management and maintenance of dignity becomes the focus of care;

- Consideration of reduction in medication;

- Prevention and management of complications, such as incontinence/ pressure sores;

- Duration 2.2 years +/− 2.2 (3).

As PD progresses a patient faces increasing symptoms and issues. Lee et al. carefully carefully assessed the needs of people with PD and found a total of 90 symptoms reported by patients, with high frequency of some symptoms—slowness of movement in 89%, pain in 85%, drooling 65%, anxiety 62%, stiffness 61%, memory issues 51%, weakness 48% and dysphagia 25% (4). Using the Palliative Outcome Scale many patients scored symptoms as overwhelming or severe, including pain, walking problems, communication, fatigue, falls, constipation and sleeping problems and the mean score showed that they had moderate palliative care needs (5). People with PD have higher admissions to hospital, longer admissions and higher mortality in hospital and an increased need for nursing home care (6). Thus, people with PD, and particularly in the later stages, have evidence of increased physical impairment, greater limitations, increased dependency and there is an increased burden on their carers (7).

For the other disorders the symptoms and needs may be very similar initially, and often PSP and MSA are initially diagnosed as PD. However, in MSA cerebellar dysfunction may be seen and autonomic features are seen more commonly—including falls, postural hypotension, erectile dysfunction and urinary problems—and in PSP there may be early falls, gaze palsy and more cognitive issues (8). There is also a poorer response to dopaminergic medication and the deterioration is quicker.

The needs will vary from person to person and over time. How they are managed may also vary and initially the main team caring for the patient may be from neurology, ensuring that the medication is effective and coping with initial disability. The wider multidisciplinary team will become increasingly involved, with physiotherapy, speech and language therapy, occupational therapy and social support increasing. As there is further progression there will be an increase in the need for the management of symptoms and other issues, together with the support of both the person with PD and their family. The role of specialist palliative care may be much wider than merely in the “Palliative care phase”.

Role of palliative care

The World Health Organization defines palliative “An approach that improves the quality of life (QOL) of patients and their families facing problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering, early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual” (9). This is thus the holistic care of a patient, and their family, looking at all aspects of care—physical, psychological, social and spiritual. However, there is often uncertainty as to the level of care needed for any particular patient. The European Association for Palliative Care has suggested that there are different levels if care:

- Palliative care approach, which should be part of all patient care, ensuring good communication with patient and family, shared decision making and goal setting and symptom management. All services should provide this basic care;

- General palliative care would be provided by primary care professionals and specialist services caring for patients with life threatening illness. Palliative care may not be the entire focus of their role but they should have additional expertise, acquired from special education and training;

- Specialist palliative care provided for patients with more complex issues, which may not be covered by other services. The team would have this as their main activity and have received specialist training and continuing education (10).

All patients should receive basic palliative care approach during their care and, in particular, those with progressive neurological disease. This has been recommended in guidelines on the care of people with PD (11) and the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) and European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Consensus paper on neurological palliative care (12).

Within the WHO definition of palliative care the services may be involved at any time within the disease progression, according to the needs of the person and their family. However, these needs and issues may not require specialist advice and specialist team involvement, if there are professionals within a team that are able to provide palliative care—listening and responding to the patient, providing psychosocial support and managing symptoms. The involvement of specialist palliative care would be for more complex issues and the professionals working in specialist palliative care would be expected to have recognised qualifications or accreditation in palliative care and may provide consultative and ongoing care for patients with a life limiting illness and provide support for their primary carer and family during and after the patient’s illness. In general, they should not be directly involved in the care of people who have uncomplicated needs (13).

There may be complex needs at any stage during this disease progression but as the palliative phase approaches there may be profound needs—for patient and family. These palliative care needs may be met by the PD multidisciplinary team or the primary health care team, of family doctor and community nursing services. The complexity of needs may be difficult to define, as all patients and families are so different in their various needs and the effects on these on their own particular circumstances. For instance, one patient may find the issues of mobility particularly stressful as they have been an active, physical person, and see their own life and role within this activity, whereas another person may be more able to accept the restrictions that are place on them due to their immobility and disease progression.

Moreover, complexity may depend on the professional carers. One team may find specific issues more difficult to cope with, or have varying expertise in managing symptoms or psychosocial issues. Hopefully, within a multidisciplinary team there is a member who is able to cope with, and manage appropriately, these various issues. However, the experience and expertise of the professionals may affect their own definition of complexity—for a physician who finds pain management difficult and is unsure about the use of medication may refer for pain management more readily than a physician and team with greater experience, expertise and confidence (14).

The involvement of specialist palliative care

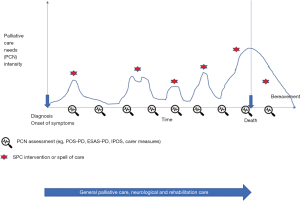

There will be times that specialist palliative care team involvement may be helpful. This may be in a more collaborative approach, working together with the wider multidisciplinary team and providing the expertise and support for the team. This may be at any time throughout the disease progression and it has been suggested that specialist involvement may vary over time. Bede et al. have suggested that whereas in the past palliative care was seen to be only in the final stages of the disease progression (Figure 1A). More recently a collaborative approach has been developed with a slow reduction in neurological support over time, with an increase in palliative care support (Figure 1B). A varying input may be more appropriate, responding to the needs of the patient and family (Figure 1C) (15). This may be challenging for all involved in care, as usually only one professional of multidisciplinary team care for the patient at any time, and the collaboration may be more difficult to manage and, in many countries, this may also cause major issues with funding of services. However, the aim should be to maximize the care for patients and families, and ensure that their QOL is as good as possible. The EAN/EAPC Consensus paper has recommended this collaborative approach and challenges all involved in neurological care to reassess the care that is provided. Within PD care an integrated model of care, involving palliative care before the palliative phase has been suggested (16).

There will be specific times that specialist palliative care may be more likely to be involved in the care of a person with PD:

Complex needs

There may be complex needs for a person with PD, and their family, at any time during the disease progression. These may be:

- Physical—symptoms such as pain, fatigue, depression, psychosis, dementia, sleep issues (including sleep disordered breathing, restless legs, REM sleep behaviour disorder), anxiety, autonomic issues (orthostatic hypotension, constipation, urinary problems, including incontinence, dysphagia, sexual dysfunction);

- Psychological issues—depression, anxiety, fear of the deterioration and of dying and death, emotional changes, emotional lability, concerns about symptoms.

- Social issues—changes within relationships (such as change in roles due to disability and increased dependency on family and carers), concerns about family members (such as concerns about the burden of care on spouse or family, worries about telling the children/grandchildren), fears for the future care of spouse or family, financial issues due to increasing disability and inability to work or family carers having to give up work to care, sexuality and intimacy concerns due to disability and physical changes. Studies have emphasized the need for psychosocial support for patients and families (18) and that there is a high burden and wish for extra support (17);

- Spiritual issues—these may be religious, relating to specific religious concerns, but may be more general relating to the meaning of the disease, coping with deterioration and fears for the future and of dying and death (19).

These may be managed by the multidisciplinary team but if there are increased issues and particular distress for the patient, and often family, a specialist palliative care approach may be helpful. Studies have shown a high illness burden for patient and families (17);

Specialist palliative care would be able to provide a multidisciplinary and specialist assessment of these issues and collaborate with the wider multidisciplinary PD team and primary care team to help improve symptom management.

Ethical issues

The care of a person with progressive PD, and their family, may lead to many ethical issues such as complex decision making—about interventions such as gastrostomy, ventilatory support/intervention for disordered breathing, deep brain stimulation, or the withdrawal or decision to withhold treatment. These will be considered later below.

There may be ethical issues relating to decision making if the person with PD has evidence of Lewy Body Dementia, as the person may not have capacity to make decisions for themselves. Advance care planning may allow the person’s wishes to be known, as they will have expressed their wishes before losing capacity—this will be discussed below.

End of life

As the person with PD deteriorates there will be the need to consider whether the end of life is expected in the coming weeks or months, as this may alter the management. However, as was discussed before the Palliative Care phase may be expected to be on average 2.2 years, with a variation of 2.2 years. This may cause the patient, family and professionals to be less sure about the disease progression and often death is unexpected.

The EAN/EAPC Consensus paper recommended the consideration of triggers for the identification of the approach of the end of life (12). In the UK a group of professionals suggested a series of triggers that may suggest that the patient was in the last 12 months of life. The triggers for all neurological patients are swallowing problems, recurring infection (especially aspiration pneumonia), marked decline in functional status, first episode of aspiration pneumonia, cognitive difficulties, weight loss and significant complex symptoms, as well as the overall impression of the professional team (20). For PD extra triggers were suggested: rigidity, pain, agitation and/or confusion from sepsis and neuropsychiatric decline (20). These were agreed by consensus but a retrospective study of patients with progressive neurological disease, including PD, did show that the number of triggers increased as death approached and aspiration pneumonia was particularly seen in the last 6 months of life (21).

A similar approach has been used by the Gold Standards Framework in the UK. The aim of the programme is to identify people at risk of dying in the coming year. Initially the “Surprise Question” is considered—“Would you be surprised if the patient died in the next year, months, weeks, days?” (22). If the answer is felt to be “no” the Guidance may help identify these patients. For PD the criteria suggested are: drug treatment less effective or increasingly complex regime of drug treatments, reduced independence, condition is less well controlled with increasing “off” periods, dyskinesias, mobility problems and falls, psychiatric signs (depression, anxiety, hallucinations, psychosis) and increasing frailty (22).

A further study has suggested that a body mass index less than 18 either alone or in combination with a change in prescribing, when dopaminergic medication may be reduced (in particular when there is a reduction to only one or two medications and the risks of side effects are outweighing the benefits) was seen in the last 6 to 12 months of life and this could signal the consideration of referral for hospice care (23). This study did not find any significant differences in the reports of symptoms or changes in care, such as admission to care facility (23).

Thus, it may be possible to identify when a person with PD is approaching the last 6 to 12 months of life and then consideration of the management may be reassessed. Specialist palliative care may be helpful at this time to help in the care and preparation of the patient and family, including discussion of place of care and death, discussion of possible withholding of some treatment, such as antibiotics or ventilatory support, consideration of a Do Not Attempt Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (No Code), provision of medication to manage potentially distressing symptoms at the end of life—pain, nausea, chest secretions, agitation—reassessment of any advance care planning, and ensuring that all involved in care are aware of the potential changes and deterioration so that in appropriate or unplanned events do not occur, such as admission to hospital when the patient wishes to remain at home.

There is certainly evidence of an unmet need as a study of the place of death of people with neurological disease in the UK showed that for PD 9.7% died at home, 43.4% in hospital and only 0.6% in hospices (24). In Germany patients with advanced PD were found to have a severely reduced QOL and 72% had an unmet need for palliative care, but only 2.6% had contact with palliative care services (25).

Thus, specialist palliative care can help in the planning for the end of life care of a person with PD so that this care is in accordance with the wishes of the person and their family. This may require complex discussion as families may have differing views and cope with the burden of care in differing ways and with varying reactions and behaviours. The specialist team may be able to help in these discussions and ensure that all are prepared for a possible deterioration—patient, family and the professionals involved.

The evidence for the effectiveness of specialist palliative care

Specialist palliative care can be considered as a complex intervention whose main outcomes are the individual QOL of patients and their families, physical symptom burden, psychosocial and spiritual issues, individual preference on care and the quality of death and dying (9). Thus, research into the effectiveness of such a complex intervention should take into account the complexity and ensure that all aspects of care are considered.

There is an increasing amount of evidence that SPC improves many of these issues in patients affected by different severe conditions. For example, home palliative care for patients, primarily, but not exclusively, with cancer, has been shown to increase the chances of dying at home and reduces symptom burden in particular for patients with cancer (26), is cost effective (27), improves QOL and reduces use of hospital and emergency services when compared to usual care in patients with serious illness (28). The intervention by a Clinical Nurse Specialist with extra training in palliative care was shown to be effective in reducing specific resource use such as hospitalizations, length of stay and health care costs (29).

Multiple studies have demonstrated several benefits of early outpatient palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. However, better designed and executed studies are needed to determine the best time to intervene and the best model of care (30,31). Increase in survival is not generally considered a palliative care outcome, but we now have evidence that early palliative care integration can improve also the life expectancy of patients in parallel with their QOL (32).

The impact of specialist palliative care for patients affected by neurodegenerative conditions, such as PD and related disorders are, has been investigated. The first evidence of positive impact were found by a phase 2 randomised control trial involving patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), which showed improvement in some key symptoms for the patients, reduced informal caregiver burden and was cost effective (33,34). This study was replicated in Italy with a similar prospective design, but involving patients with other neurodegenerative conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), MS and PD and related disorders. Fifty patients were randomized to receive immediate specialist palliative care versus standard care. This study showed how patients who received the specialist input, from a multidisciplinary specialist palliative care team visiting on a regular basis, reported a significant clinical and statistical improvement in individual QOL and in important physical symptoms like pain, dyspnoea, quality of sleep, and bowel symptoms compared to those who received standard care form their primary health care team (35).

Results from a wide national study in the UK, exploring the clinical and cost effectiveness of short-term integrated palliative care services to optimise care for people with advanced long-term neurological conditions, including PD and related disorders, are waited in order to have stronger evidence and provide recommendations on the most effective models of care. Preliminary results demonstrate the opportunity to increase collaboration between neurology and palliative care services for people with progressive neurological conditions, and the acceptability of a short term intervention as a model to support this (36).

Effectiveness of specialist palliative care in PD and related disorders remains an unsolved issue in terms of service provision. Bouça-Machado and colleagues, exploring the need for palliative care for patients with PD and their families, showed that palliative care unmet needs are present along all the disease trajectory, and they advocate for an early, integrated and simultaneous palliative care intervention. They concluded that many problems affecting this population need palliative care skills, assessment and treatments, but state that, although promising, there is still a need to demonstrate the effectiveness of palliative care for patients with PD (37).

The most promising model of specialist palliative care intervention remains the one based on needs and complexity. Literature proposes triggers for palliative care interventions (12), but it is not clear how to assess the intensity or complexity of care that may require specialist palliative care intervention. Although end of life care remains paramount for specialist palliative care, due to the patients’ symptoms and psycho-social-existential burden, caregivers’ distress, respect for patients’ choices and bereavement care, other input during the disease course should be available. One possible indication could derive from a scheduled assessment of palliative care needs, using validated tools (see for example ESAS-PD, POS-PD, IPOS and caregivers’ burden measures described above). When the needs intensify, which can be evaluated in terms of severity of one or more problems, or using the measurement tool total score, justify a specialist intervention then it can be the time for a specialist referral. The intervention will depend on the issue, and will continue until a further assessment shows a decrease in the users’ intensity of needs as seen in Figure 2. If the needs are shown to increase again later there may be further involvement.

Ethical decision making

There is an increasing role for specialist palliative care in the facilitation of complex decision making, and supporting all involved—patient, family and professionals. There are increasingly more difficult decisions to be made, and for the person with PD there are increasing issues, as the disease progresses, of communication issues due to speech becoming more difficult and cognitive change.

In PD around 15% of patients have a mild cognitive impairment that can be present at the time of diagnosis (38) and up to 80% of patients will develop a frank dementia, Lewy Body Dementia, overtime (39). Although frank dementia is not common in MSA, frontal lobe dysfunction with attention deficits has been reported in one third of cases, with emotional incontinence and behavioural changes, including depression, anxiety, panic attacks, and suicidal ideation (40). In PSP up to 40% of patients have a severe dementia at diagnosis and cognitive decline occurs in a great proportion of patients early during the disease course (41). In coticobasal degeneration (CBD) dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) dementia is very frequent at early stages and almost always present in the advanced phases (42).

Mental capacity, which is the ability to make decisions related to one own’s health, may be strongly impaired in patients with PD and related disorders. In the advanced stages patients cannot express their opinions on care and they are often institutionalized and clinicians have to make decisions based on patients’ best interests. Families and proxies can help in the decision making process, but are often overwhelmed by the relentless deterioration of their beloved one, and sometimes do not want to be involved in difficult choices or there may be different opinions within the family contest. However, there may be many decisions to be made:

- Medication decisions—including consideration of infusion medication;

- Deep brain stimulation may be discussed, or if this has been started as the patient deteriorates there may be consideration of withdrawal;

- Consideration of gastrostomy placement if there is severe dysphagia, or consideration of withdrawal of feeding through an already placed tube as the advanced stages are reached;

- Consideration of respiratory support—such as CPAP for sleep disorders or tracheostomy for someone with MSA who is experiencing episodes of stridor.

- End of life decisions:

- Place of care and place of death;

- Resuscitation status;

- Use of antibiotics at the end of life;

- Discussions about hastening death—euthanasia or physician assisted suicide, even if these are not options within the legislation of the patient, they may still be discussed;

- Withdrawal or withholding of other treatment options—although it may be very important to continue dopaminergic medication for a patient with PD to prevent more symptoms developing—using apomorphine infusion, intestinal gel preparations (43), dispersible preparations via a gastrostomy, transdermal preparations.

The decisions about treatments may be complex, balancing the benefits and the side-effects (44). It may be very difficult for patients, due to communication or cognitive issues, and families to make these decisions. For instance, adverse reactions to deep brain stimulation can be subsequent to the surgical procedure or to the stimulation itself and the most common serious adverse effect is surgery-related intracranial haemorrhage, as are infections and mispositioning, dysarthria, depression, or dyskinesias. Apomorphine can worsen hallucinations and cause psychosis, sedation and somnolence. Levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel therapy requires the positioning of a jejunostomy tube inserted through percutaneous gastrostomy (PEGJ) which if often cause of problems due to dispositioning, occlusions or local infections.

There may be ethical issues related to the expectations that may be held by patients and families. It must be clear that those are all palliative interventions are unable to prevent the disease progression. As all conventional treatments are all expected to fail over time, their withdrawal should be discussed at the time of onset. Very little is known about how and when these treatments are to be withdrawn and what is the impact on patients and families. It is always easier to present a new treatment from the positive side, but patients and families should also be informed of the limitations of these advanced treatments.

For these reasons the role of advance care planning is strongly advocated as early as possible in the disease trajectory. The EAN/EAPC Consensus paper strongly advocates for the use of structured communication tools in order to facilitate the introduction of bad news (12). Improving communication skills should create a positive environment which facilitates the shared advance decision making. Knowing that patients will lose their capacity to decide and then helping them to understand these issues and plan ahead can be very difficult and lead to many ethical discussions. Clinicians may fear to create anxiety announcing what will happen in the future, but if patients and families are not offered these opportunities to discuss the future and their own wishes at this earlier time, when they are able to do so, their preferences will not be known.

Specialist palliative care has a role in helping with these discussions in these very complex areas. Moreover, communication and discussion within the complex families of patients may require considerable skill, in communication and family dynamics.

Collaboration between specialist palliative care and PD care

Specialist palliative care has an important role in the care of people with PD, and their families. This is in addition to, and in collaboration with, a wider multidisciplinary team approach for these patients, where a specialist team, working in movement disorders and including not only neurologists and specialist nurse but other disciplines, including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, psychological support, dietitian, spiritual support, speech and language therapy and counselling/social care.

The involvement of specialist palliative care has been shown to be effective and at the end of life there are potential triggers facilitating referral. However, throughout the disease progression there may be a role for managing complex issues and for other complicated issues, such as difficult decisions or ethical dilemmas. There is a need for greater awareness of all involved in PD care for the involvement of specialist palliative care, when the more generic palliative care that they are providing is not adequate or allowing the maximization of QOL. There are now several assessment tools that may be used on a routine basis with the aim of elucidating these complex issues. These include:

- Palliative care Outcome Scale-Symptoms Parkinson’s disease (POS-PD)—which is completed by patients and rates their symptoms from “Not at all” to “Overwhelmingly” (5);

- The Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease Parkinson’s Disease (NAT:PD)—which has “Red flag” areas of severe symptoms, such as hallucinations, recurrent falls, pneumonia or choking, 24 hour care, clinic non-attendance, Hoehn and Yahr stage 3; issues of patient well-being, such as psychological or spiritual issues, financial concerns, health beliefs, cultural issues; family and carer issues of their difficulties in coping with care; and carer well-being. This can be completed by the professionals in collaboration with the patient and family/carers to show serious issues (16);

- The Edmonton Symptom assessment Scale for PD (ESAS-PD) considers symptoms and may demonstrate the responsiveness to intervention in PD (45);

- PDQ-39—looking at how people with PD are affected in 8 dimensions of daily living (25);

- Hoehn and Yahr scale of disease severity does show the level of disability but this may not relate to QOL or complex symptoms or other issues.

These scales can help to identify patient and families with particular issues and allow monitoring after management has been started to see how effective this has been. In this way the awareness of the role and possibilities of specialist palliative care can be raised.

Such scales have been used in practice. In Toronto, Canada a multidisciplinary team, including both a movement disorders neurologist and a palliative medicine physician used the ESAS-PD and showed that several items on the scale improved after the patient was seen in this MDT—constipation, dysphagia, pain and drowsiness (45). A different regime was developed in Oregon where the routine appointments were with a neurology-based team, but a palliative medicine physician joined the clinic for more challenging cases (46). The issues that benefitted from the collaboration were psychosocial support, complex symptom management and advance care planning. Good relationships were also developed with other specialist palliative care services and hospices in the community, building on this collaboration (46).

An International Working Group meeting on PD and Palliative Care in 2015 reinforced the need for collaboration, needs assessment, assessment of caregiver needs, the development of new interventions and new research (47). From the international perspective the meeting also acknowledged that earlier palliative care involvement could cause issues for services who may find it difficult to have ongoing involvement, over years, and there may be reimbursement issues for the care they provide (47).

Specialist palliative care services may be reluctant to be involved with neurological disease patients as there are concerns about the care that may be needed and their lack of expertise in managing the medication in PD. A qualitative study in Canada suggested that there were specific challenges: the variability and long timelines of progression of the disease; barriers to communication due to speech or cognitive issues; the uncertainty of prognosis, disease trajectory and support; inconsistent information as many team members and even different teams may be involved in care; existential distress, including emotional, psychological and spiritual distress of patient, families and professionals due to the loss of function, autonomy issues and dying and death (48).

These issues may reflect the need for professional education and support, which was recommended by the EAN/EAPC Consensus paper (12). There is need for palliative care education for neurologists and neurology training for palliative care specialists, both in training and in continuing medical education. This is a challenge and awareness of the issues that may arise within teams, and between different teams caring for the same patient, is often lacking (49).

In the USA a new subspecialty of “Neuropalliative care” has been developing, with neurologists undertaking extra training in palliative medicine and thus being able to focus on the specific needs of patients with neurological illness (50). A Neuropalliative Care Summit in 2017 suggested the need for new models of integrated care; new quality measures; the alignment of financial and other incentives to facilitate care; access to education; epidemiology and outcomes research (50). At the same time there has been a movement to enable neurologists to provide primary palliative care, ensuring treatment does align with patient preferences, a multidisciplinary approach managing symptoms, discussing serious issues more openly and introducing specialist palliative care (51).

Conclusions

There is an increasing role for specialist palliative care in the overall care for people with PD, and their families. This would be in a collaboration with other services—both neurology and primary care—so that a palliative care approach can be available for all patients from diagnosis, with specialist advice and support for the more complex issues. There is a need for all services to adapt to these challenges, but with the aim of improving the QOL of people with PD, the care for their families and the effectiveness and resilience of the professionals involved.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Chiu WZ, Kaat LD, Seelaar H, et al. Survival in progressive supranuclear palsy and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:441-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faniciulli A, Wenning GK. Mutiple-System Atrophy. N Eng J Med 2015;372:249-63. [Crossref]

- Thomas S, MacMahon D. Parkinson’s disease, palliative care and older people; part 1. Nursing Older People 2004;16:22-4.

- Lee MA, Prentice WM, Hildreth AJ, et al. Measuring symptom load in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2007;13:284-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saleem TZ, Higginson I, Chaudhuri KR, et al. Symptom prevalence, severity and palliative care needs assessment using the Palliative Outcome Scale: a cross-sectional survey of patients with Parkinson’s disease and related neurological conditions. Palliat Med 2013;27:722-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tomaszewicz M, Rossner S, Schliebs R, et al. The clinical symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 2016;139:318-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bouça-Machado R, Lennaerts-Kats H, Bloem B, et al. Why palliative care applies to Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2018;33:750-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiblin L, Lee M, Burn D. Palliative care and its emerging role in Multiple Systems Atrophy and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;34:7-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2002). Palliative care. Available online: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Radbruch L, Payne S. White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 1. Eur J Palliat Care 2009;16:278-89.

- Parkinson’s disease in adults. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017. Available online: Nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71

- Oliver DJ, Borasio GD, Caraceni A, et al. A consensus review on the development of palliative care for patients with chronic and progressive neurological disease. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:30-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palliative Care Australia, A Guide to Palliative Care Service Development: A population based approach, PCA, Canberra, 2005.

- Oliver D. Improving patient outcomes through palliative care integration in other specialized health services: what we have learned so far and how can we improve? Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:S219-230. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bede P, Hardiman O, O’Brannagain D. An integrated framework of early intervention palliative care in motor neurone disease as a model to progressive neurodegenerative disease. Poster at European ALS congress, Turin 2009.

- Richfield EW, Jones EJS, Alty JE. Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: A summary of the evidence and future directions. Palliat Med 2013;27:805-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fox S, Cashell A, Keornohan WG, et al. Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: patient and carers’ perspectives explored though qualitative interview. Palliat Med 2017;31:634-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan KY, Chan ML. Enhanced psychosocial support as an important component of neuro-palliative service. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:355-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lambert R. Spiritual care. In: Oliver D, Borasio GD, Johnston W. editors. Palliative care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis- from diagnosis to bereavement. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014:171-86.

- End of life care in long term neurological conditions: a framework for implementation. National End of Life Care Programme 2010.

- Hussain J, Adams D, Allgar V, et al. Triggers in advanced neurological conditions: prediction and management of the terminal phase. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:30-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gold Standards Proactive Identification Guidance. The Gold Standards Framework 2018. Available online: http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/PIG

- Goy ER, Bohlig A, Carter J, Ganzini L. identifying predictors of hospice eligibility in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:29-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sleeman KE, Ho YK, Verne J, et al. Place of death, and its relation with underlying cause of death, in Parkinson’s disease, motor neurone disease, and multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Palliat Med 2013;27:840-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klietz M, Tulke A, Muschen LH, et al. Impaired quality of life and need for palliative care in a German cohort of advanced Parkinson’s disease patients. Frontiers in Neurology 2018;9:120. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013.CD007760. [PubMed]

- Smith S, Brick A, O’Hara S, et al. Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med 2014;28:130-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cunningham C, Ollendorf D, Travers K. The Effectiveness and Value of Palliative Care in the Outpatient Setting. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:264-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salamanca-Balen N, Seymour J, Caswell G, et al. The costs, resource use and cost-effectiveness of Clinical Nurse Specialist-led interventions for patients with palliative care needs: A systematic review of international evidence. Palliat Med 2018;32:447-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis MP, Temel JS, Balboni T, et al. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann Palliat Med 2015;4:99-121. [PubMed]

- Bradley N, Lloyd-Williams M, Dowrick C. Effectiveness of palliative care interventions offering social support to people with life-limiting illness-A systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2018;27:e12837. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, McCrone P, Hart S, et al. Is short-term palliative care cost-effective in multiple sclerosis? A randomized phase II trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:816-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edmonds P, Hart S, Gao W, et al. Palliative care for people severely affected by multiple sclerosis: evaluation of a novel palliative care service. Mult Scler. 2010;16:627-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Veronese S, Gallo G, Valle A, et al. Specialist palliative care improves the quality of life in advanced neurodegenerative disorders: NE-PAL, a pilot randomised controlled study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:164-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hepgul N, Gao W, Evans CJ, et al. OPTCARE Neuro group. Integrating palliative care into neurology services: what do the professionals say? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018;8:41-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bouça-Machado R, Titova N, Chaudhuri KR, et al. Palliative Care for Patients and Families With Parkinson's Disease. Int Rev Neurobiol 2017;132:475-509. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aarsland D. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;22 Suppl 1:S144-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hely MA, Reid WG, Adena MA, et al. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson’s disease: the inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov. Disord 2008;23:837-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhatia KP, Stamelou M. Nonmotor Features in Atypical Parkinsonism. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;134:1285-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pilotto A, Gazzina S, Benussi A, et al. Mild Cognitive Impairment and Progression to Dementia in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Neurodegener Dis 2017;17:286-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Erkkinen MG, Kim MO, Geschwind MD. Clinical Neurology and Epidemiology of the Major Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lex KM, Kundt FS, Lorenzl S. Using tube feeding and levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel application in advanced Parkinson's disease Br J Nurs 2018;27:259-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Worth PF. When the going gets tough: how to select patients with Parkinson’s disease for advanced therapies. Pract Neurol 2013;13:140-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyasaki JM, Long J, Mancini D, et al. Palliative care for advanced Parkinson disease: an interdisciplinary clinic and new scale, the ESAS-PD. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:S6-S9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kluger BM, Persenaire MJ, Holden SK, et al. Implementation issues relevant to outpatient palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:339-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kluger BM, Fox S, Timmons S, et al. Palliative care and Parkinson’s disease: meeting summary and recommendations for research. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;37:19-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gofton TE, Chum M, Schultz V, et al. Challenges facing palliative neurology practice: a qualitative analysis. J Neurol Sci 2018;385:225-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oliver D, Watson S. Multidisciplinary Care. In: Oliver D. editor. End of Life Care in Neurological Disease. London: Springer, 2012;113-27.

- Creutzfeldt CJ, Kluger B, Kelly AG, et al. Neuropalliative care. Priorities to move the field forward. Neurology 2018;91:217-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Creutzfeldt CJ, Robinson MT, Holloway RG. Neurologists as palliative care providers. Communication and practice approaches. Neurology 2016;6:40-8. [PubMed]