Residents’ reflections on end-of-life conversations: how a palliative care clinical rotation creates meaningful learning opportunities

Introduction

Studies suggest that good physician communication at the end of life can positively impact decision making in patients with serious illness (1), reduce length of stay in the intensive care unit (2-4), decrease non-beneficial life-sustaining interventions (5,6), and improve patient and family satisfaction with end of life care (7,8).

A goals of care (GOC) discussion can clarify a patient’s understanding of their illness and confirm a health care provider’s understanding of their patient’s values and goals (9). These conversations cover complex content and require a delicate approach (10-12). Physicians often find it difficult to engage in these discussions for a variety of reasons, including inadequate training (1,10,12-17).

Palliative care training during residency may be an optimal time to set the groundwork for developing good communication behaviors (14). Several studies have shown that classroom-based training can improve residents’ communication skills regarding end-of-life (18,19), serious illness (20) code status (21-23), giving bad news (21,24), and GOC (24). Further, hands-on training in a palliative care setting has been associated with self-perceived (25,26) and demonstrated (16,27) improvements in residents’ communication skills. However, it is not clear whether communication with terminally ill and dying patients is deliberately taught at bedside, or an inadvertent lesson learned (28). While these studies highlight that classroom or bedside training may improve GOC conversation skills, they do not explore the mechanisms—namely the learning environment and activities—that facilitate skill development.

Studies that describe residents’ end-of-life communication training experiences have primarily focused on quantifying trainees’ exposure to certain learning activities or palliative care communication (29-33). However, these studies do not explain the educational value of these experiences. Further, none of these studies specifically focused on training within a palliative care context or training with a specialized palliative care center.

A previous publication on a subset of our data reported that training in a specialized palliative care setting increased family medicine residents’ capacity to manage pain and symptoms, and communicate with patients and families. However, it may have also inadvertently reinforced a message that palliative care is a specialized area of medicine (34).

The purpose of this study is to explore family medicine residents’ perceptions of their GOC training over a 4-week rotation with a specialized palliative care center, specifically focusing on residents’ self-perceived development, and identifying elements of the training that may facilitate communication skills development.

Methods

Design

This is a qualitative secondary analysis of a previously collected data set. We used Inductive Thematic Analysis (35) to analyze semi-structured interviews with family medicine residents and explore their educational experiences during a palliative care rotation. The hospital research ethics board approved this study.

Participants

Information letters describing the study were emailed to all first-year and second-year family medicine residents completing a four-week rotation at a specialized palliative care center. A total of 25 residents completed a rotation at the center from July 2013 to June 2014. The study primary investigator (RM) is a physician with the center’s inpatient team and was in a supervisory role to some participants. In order to protect participant identity and reduce potential response bias, the study coordinator (AMK), who had no involvement in the participants’ educational experiences or evaluations, completed all recruitment. RM’s role was made known to participants during the consent process.

Educational experience

The center offers palliative care services to patients in their homes, as well as inpatient consultations. Residents spent two weeks in each environment. In the home environment, residents accompanied palliative care physicians on patient home-visits. In the inpatient environment, residents worked with a palliative care consultation team consisting of two palliative care physicians and one clinical nurse specialist in an urban teaching hospital. No standardized teaching methods or curriculum were utilized throughout the training, other than weekly didactic seminars.

Data collection

Residents first completed a brief survey about their previous palliative care experience. Following their rotation, participants completed a semi-structured, one-on-one interview about their educational experience during the rotation and their perceived roles as family physicians in the delivery of palliative care. The interview guide was developed by the PI and the study coordinator with feedback from the research team. The study coordinator conducted the interviews in person or over the phone (36). Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Transcripts were de-identified, and referred to by study ID during analysis. The study coordinator compared completed transcripts to the audio recordings to verify accuracy.

Data analysis

We used a thematic analysis approach (35) to organize and describe participant experiences and perceptions. After the first 6 interviews had been completed, two reviewers (RM and AMK) collaboratively reviewed the transcripts and generated a list of codes based on high-level recurring concepts. Using NVivo software (Version 10), the codes were then independently applied line-by-line to the initial 6 and each of the 9 subsequent interviews as they were completed. New codes were created and applied as required. Interview questions were modified as necessary to probe emerging areas of interest.

During two subsequent meetings, the reviewers compared their application of codes to the interviews to achieve consensus. RM, AMK, and JW, a home-environment physician from the palliative care center, reviewed the data within the codes related to communication and teaching strategies to identify patterns across participant responses.

Throughout the analysis and writing process, emerging themes were checked against the data to ensure that themes were representative of participant responses. Through this process of pattern identification and refinement, the research team determined that no new dimensions or insights were emerging, indicating that we had achieved saturation (37). Coding and interviewing were terminated at this time.

Results

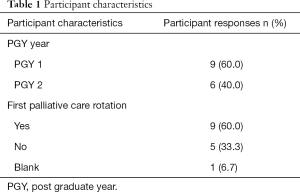

Of twenty-two residents that consented to participate, 15 completed interviews, which lasted 15–30 minutes. Seven residents did not complete interviews due to time restrictions or lack of response. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Of the 15 participants, nine were first-year residents and six were second-year residents. Sixty percent of participants indicated this was their first palliative rotation (n=9). Of these participants, 4 (44%) indicated they had previous exposure to palliative care during medical school training.

Full table

Learner perceptions of their communication skill development

Participants indicated that learning how to have a GOC conversation was a valuable part of the rotation that would serve them in their future family practice.

“I think the most important thing that I took home was the communication piece and I saw some really great ways of approaching things that I wouldn’t necessarily feel comfortable approaching myself or would have been before” (PGY2-1).

Participants often described feeling more competent and comfortable conducting GOC conversations at the end of the rotation.

“I’d say the GOC discussions and family meetings are definitely something I’m more comfortable with now. I’ve had the chance to see experts do them a few times and I think I’ve gained some tips watching them” (PGY1-13).

Elements of training that were valuable for communication skill development

We identified two themes that describe elements of the rotation that were valuable for GOC communication development. These include: (I) a constructive learning environment, and (II) structured learning activities.

A constructive learning environment

Participants described two factors that created an environment that promoted engagement in GOC conversations: (I) adequate time for having GOC conversations, and (II) preceptor support.

Adequate time for GOC conversations

Participants did not feel rushed, which allowed them to engage in meaningful GOC conversations with patients and families. This was contrasted with other rotations, where residents have less time for patient interactions in order to get through a larger volume of cases.

“I could sit there and talk to them [patients] whereas all the other rotations it’s quick, quick, okay, what’s their medical issue and let’s resolve their medical issue.” (PGY2-2).

Preceptor support

Participants felt supported in their learning when their preceptors were available to help during conversations if the resident was not sure what to do.

“I was able to lead interviews with patients, but I always felt that I was really supported and that there was someone with more experience close by” (PGY1-5).

For many residents, this was their first time participating in the care for dying patients and participants described having opportunities to reflect on specific conversations, their feelings about death and dying, and the rotation overall with their preceptors.

“I felt like there was a lot of opportunity to reflect, and ask questions, even if it wasn’t just about the discussion, but about how I was feeling about what I was talking about, or seeing, which was good.” (PGY2-4).

Structured learning activities

Within the constructive learning environment, residents described three types of learning activities that facilitated development of their GOC communication skills: (I) preceptor modeling, (II) supervised resident-led discussions, and (III) independent practice. These learning activities were described along a continuum of independence.

“She [preceptor] took it step by step. She let me watch her first and then she let me control everything while she was in attendance, and then she’d let me do things on my own, and then she would come back and review. It was a good progression, in terms of how she gave me my independence” (PGY2-2).

Preceptor modeling

At the beginning of their rotation, most residents described feeling inadequately prepared to have GOC conversations with patients and families. At these times, preceptors led the conversation to demonstrate key aspects of effective GOC discussions. Residents valued these opportunities for observation and indicated that this degree of guidance was unique to this rotation. Participants felt that observing experts have these conversations improved their understanding of the key elements of GOC conversations.

“Speaking about goals of care with families and having family meetings, I think, is also something we don’t get a lot of experience with [in other rotations]… That was also a huge learning opportunity, just to see how the staff lead those meetings” (PGY1-3).

A few residents did not have this opportunity to observe expert-led interactions, which they identified as a missed learning opportunity.

“[The patient] was so angry about his diagnosis he did not want to talk about it at all. I felt like I was shadowboxing a little bit and not really getting anywhere. I know one of the staff went in later to see him, and I thought that would have been helpful for me to watch to see how they worked their magic in that space.” (PGY1-8).

Supervised resident-led discussions

Residents described being given the opportunity to lead GOC conversations, but with the preceptors in the room observing. Some residents were uncomfortable being observed but ultimately appreciated these opportunities for hands-on practice, and targeted feedback from preceptors.

“I always find it awkward when someone is watching you because I feel more nervous, and I'm not as comfortable as if I’m just by myself. But, I felt like that I hadn’t had a lot of end-of-life discussions, so, I was also uncomfortable talking about it, so, it was good to get the feedback like, ‘you asked this well’, or, ‘you brought it up well, don’t forget to ask this and that’” (PGY2-4).

Residents contrasted this experience with other rotations where they were given total independence with minimal support.

“I guess [the level of support] just surprised me because my previous experience was kind of like I’d be on a rotation and I would be told to go tell someone that they were dying, or I would have to go get a code status on someone who I had just met.” (PGY1-5).

Supervised, resident-led discussions were challenging when patients and families directed their communication to the preceptor, placing the resident in a more passive role.

“The other issue is when you’re with a staff seeing a patient… Even if [the preceptor] sets out to give you all the independence, it ends up being that the patient’s family will bring the staff into the conversation because it’s just automatic; that when [the preceptors] are sitting there they get pulled in.” (PGY1-6).

Independent practice

Finally, residents described opportunities to independently put their skills into practice. In these instances, residents engaged in conversations with patients and families without preceptors in room, but still had access to them for help or debriefing.

“There was lots of trying to encourage me to be independent and assess patients on my own and take on some of the more difficult parts of the conversation, which I appreciated. So lots of independent learning…” (PGY1-10).

Residents noted they had more opportunities for independent practice with patients in the inpatient environment. This was contrasted with the home setting, where residents and preceptors travelled together to all patient visits. As a result, there were fewer opportunities for independent, unsupervised patient encounters.

“In the community I observed the goals of care conversations for the most part and then I did one or two on my own. I guess two on my own with one being observed. And then the inpatient was basically all, I think, me” (PGY2-12).

Discussion

Our study explored resident perceptions of their learning experiences during a rotation with a specialized palliative care center. Residents felt that having GOC conversations with patients and families were meaningful experiences that would be relevant to their future practices, and they were more comfortable having these conversations at the end of the rotation. This finding is relevant given that effective GOC discussions can positively influence patient satisfaction (7,8) and patient care (1,5,6) yet family physicians feel inadequately trained to discuss treatment preferences and values with their patients (1,12-17).

Residents described several elements of the training experience that may have facilitated their communication skill development. These included a constructive learning environment (i.e., ample time for, and support during and after GOC conversations) and specific learning activities (i.e., modelling, supervised practice, and independent practice).

Residents suggested that they were given increasing degrees of independence over the course of the rotation. This resonates with the concepts of progressive independence (38-40), and entrustment in competency-based medical education (41). These concepts suggest that as residents develop and demonstrate increasing competence, their needs for instruction and supervision decrease, and they are afforded increasing degrees of responsibility and independence.

Learning that occurs under direct supervision of faculty presents important educational opportunities. For example, preceptors can verbally explain the rationale, rules and boundaries that guide expert clinical decision-making at the time care is provided (40,42,43). As well, observing residents at the bedside allows preceptors to provide immediate and specific feedback (42-44) about areas for improvement, which can then be addressed in future patient encounters (44). Residents in other studies have noted the value of observing senior staff (32,33,45) and receiving targeted feedback (32,45). However, these opportunities may be limited during residency. Most studies report that only 23–50% of residents have an opportunity to watch senior physicians discuss advanced directives or end-of-life care (31,32,46). Similarly, few residents report being observed or receiving feedback on their communication during rotations (20,31-33,45). This could have negative learning implications as learners miss out on valuable formative feedback aimed at supporting clinical skill development (47).

In later stages of training, residents may be afforded greater degrees of responsibility and independence. Residents in our study valued independence with support from their preceptor. It has been argued that unsupervised practice in a supportive training environment is necessary to prepare residents for real life practice where they will be acting completely independently (41).

The nature of a palliative care rotation may lend itself to these types of activities in a way that other rotations do not; patient encounters in the home and inpatient environments are often longer in duration with an emphasis on complex conversations. This allows for equal prioritization between patient care and teaching that is responsive to resident learning needs in a way that may not be possible in acute care environments (48,49). This also provides an opportunity to practice responding genuinely to human suffering rather than following scripted instructions that lack empathy (50). Given that participants noted fewer opportunities for independent practice in the home setting, preceptors in the community environment must make intentional efforts to ensure residents have adequate opportunities for independent practice.

Our findings highlight the elements of a palliative care rotation that were meaningful to residents and empowered them to feel comfortable having GOC discussions with patients. However, it is important to recognize that the needs of learners vary. Indeed, the flexibility needed for skilled conversations is mirrored in the responsiveness and reflexivity needed to teach this skill. Movement back and forth between the three stages of independence described by residents is more realistic than a continuous progression; as residents develop and reflect on their skills, it is important to identify areas of weakness and address them by re-engaging in this iterative learning cycle. This should not be viewed as a regression, but rather as a natural part of the learning process.

Limitations

As this study was conducted within one comprehensive palliative care program in a large urban center, there may be limited generalizability from these findings to other palliative programs. Future research should explore whether this study’s findings of effective teaching processes regarding GOC conservations may be applicable to trainees’ experiences in different palliative care programs. Further, residents’ reports of what was effective for their learning may not actually correlate with improved communication from the patients’ or families’ perspectives, particularly in the long-term. Further study is needed to understand how patients perceive GOC conversations following resident training in this area.

Conclusions

Through this qualitative study, we found that residents value a teaching environment that prioritizes learning and a teaching approach that affords them various degrees of independence in GOC discussions. Residents observed preceptors having GOC conversations, demonstrating empathy, compassion, and honesty. They further benefitted from having conversations with patients in a supportive, learning-focused environment that provided opportunities for feedback and reflection. Finally, residents were given ample time to independently practice and refine their skills, which was perceived as a key component to their development.

Underscoring this continuum of independence was an environment that supported residents’ educational journeys. Prioritizing learner development in having GOC conversations and allowing time for residents to develop relationships with patients were vital components of this environment.

It is essential that faculty members who are skilled in communication be available for mentoring residents early in their training. The nature of palliative care lends itself to purposefully guiding resident development of GOC conversation skills. Improving residents’ skills to have effective conversations with patients and families will ultimately improve patient satisfaction (7,8) and the quality of care they receive at end-of-life (1-6).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Russell Goldman, Director, Sinai Health System Inter-departmental Division of Palliative Care & Director, Temmy Latner Centre for Palliative Care for his involvement in conceptualization and ongoing support of this study; and the Temmy Latner Centre for its research support.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm.2020.03.19). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the institutional ethics review board of Mount Sinai Hospital (13-0139-E).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Hickman SE. Improving Communication Near the End of Life. Am Behav Sci 2002;46:252-67. [Crossref]

- Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M. Improving family communications at the end of life: Implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resource use. Am J Crit Care 2003;12:317-23; discussion 324. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lilly CM, Sonna LA, Haley KJ, et al. Intensive communication: four-year follow-up from a clinical practice study. Crit Care Med 2003;31:S394-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA, Barker LK, et al. Changing the culture around end-of-life care in the trauma intensive care unit. J Trauma 2008;64:1587-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen J, Robinson E, Jackson V, et al. Development of a cognitive model for advance care planning discussions: results from a quality improvement initiative. J Palliat Med 2011;14:331-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Molloy DW, Guyatt GH, Russo R, et al. Systematic implementation of an advance directive program in nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000;283:1437-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaufer M, Murphy P, Barker K, et al. Family satisfaction following the death of a loved one in an inner city MICU. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2008;25:318-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- You JJ, Dodek P, Lamontagne F, et al. What really matters in end-of-life discussions? CMAJ 2014;186:E679-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Myers J, Steinberg L, Incardona N. Discussions Contributing to Informed Consent. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license. 2016. Image Available In: Wahl JA, Dykeman MJ, Walton T. Health Care Consent, Advance Care Planning, and Goals of Care Practice Tools: The Challenge to Get It Right. (pp. 5) Toronto, ON: Law Commission of Ontario; 2016. Available online: https://www.lco-cdo.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/ACE%20DDO%20Walton%20Formatted%20Dec%202%2C2016%20LCO.pdf

- Balaban RB. A physician's guide to talking about end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:195-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epstein RM, Alper BS, Quill TE. Communicating Evidence for Participatory Decision Making. JAMA 2004;291:2359-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larson DG, Tobin DR. End-of-Life Conversations: Evolving Practice and Theory. JAMA 2000;284:1573-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buckman R. How to Break Bad News: A guide for Health Care Professionals. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1992.

- Frist WH, Presley MK. Training the next generation of doctors in palliative care is the key to the new era of value-based care. Acad Med 2015;90:268-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues, Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015.

- von Gunten CF, Twaddle M, Preodor M, et al. Evidence of improved knowledge and skills after an elective rotation in a hospice and palliative care program for internal medicine residents. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2005;22:195-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wear D. ‘‘Face-to-face with it": Medical Students' Narratives about their End-of-Life Education. Acad Med 2002;77:271-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clayton JM, Butow PN, Waters A, et al. Evaluation of a novel individualised communication-skills training intervention to improve doctors' confidence and skills in end-of-life communication. Palliat Med 2013;27:236-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams DM, Fisicaro T, Veloski JJ, et al. Development and evaluation of a program to strengthen first year residents' proficiency in leading end-of-life discussions. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2011;28:328-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tam V, You JJ, Bernacki R. Enhancing Medical Learners' Knowledge of, Comfort and Confidence in Holding Serious Illness Conversations. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;36:1096-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alexander SC, Keitz SA, Sloane R, et al. A controlled trial of a short course to improve residents' communication with patients at the end of life. Acad Med 2006;81:1008-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Szmuilowicz E, Neely KJ, Sharma RK, et al. Improving residents' code status discussion skills: a randomized trial. J Palliat Med 2012;15:768-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wayne DB, Moazed F, Cohen ER, et al. Code status discussion skill retention in internal medicine residents: one-year follow-up. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1325-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Szmuilowicz E, el-Jawahri A, Chiappetta L, et al. Improving residents' end-of-life communication skills with a short retreat: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 2010;13:439-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liao S, Amin A, Rucker L. An innovative, longitudinal program to teach residents about end-of-life care. Acad Med 2004;79:752-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peh TY, Yang GM, Krishna LKR, et al. Do Doctors Gain More Confidence from a Longer Palliative Medicine Posting? J Palliat Med 2017;20:141-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vergo MT, Sachs S, MacMartin MA, et al. Acceptability and Impact of a Required Palliative Care Rotation with Prerotation and Postrotation Observed Simulated Clinical Experience during Internal Medicine Residency Training on Primary Palliative Communication Skills. J Palliat Med 2017;20:542-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kriesen U, Altiner A, Muller-Hilke B. Perception of bedside teaching within the palliative care setting-views from patients, students and staff members. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:411-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baker JN, Torkildson C, Baillargeon JG, et al. National survey of pediatric residency program directors and residents regarding education in palliative medicine and end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2007;10:420-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Billings ME, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. Medicine residents' self-perceived competence in end-of-life care. Acad Med 2009;84:1533-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buss MK, Alexander GC, Switzer GE, et al. Assessing competence of residents to discuss end-of-life issues. J Palliat Med 2005;8:363-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rhodes RL, Tindall K, Xuan L, et al. Communication About Advance Directives and End-of-Life Care Options Among Internal Medicine Residents. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:262-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tulsky JA, Chesney MA, Lo B. See one, do one, teach one? House staff experience discussing do-not-resuscitate orders. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1285-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mahtani R, Kurahashi AM, Buchman S, et al. Are family medicine residents adequately trained to deliver palliative care? Can Fam Physician 2015;61:e577-82. [PubMed]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77-101. [Crossref]

- Holt A. Using the telephone for narrative interviewing: a research note. Qual Res 2010;10:113-21. [Crossref]

- Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual Health Res 2017;27:591-608. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dornan T, Boshuizen H, King N, et al. Experience-based learning: A model linking the processes and outcomes of medical students' workplace learning. Med Educ 2007;41:84-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kennedy TJT, Lingard L, Baker GR, et al. Clinical oversight: Conceptualizing the relationship between supervision and safety. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1080-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kennedy TJT, Regehr G, Baker GR, et al. Progressive independence in clinical training: a tradition worth defending? Acad Med 2005;80:S106-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ten Cate O, Hart D, Ankel F, et al. Entrustment Decision Making in Clinical Training. Acad Med 2016;91:191-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: A general overview. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15:988-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piquette D, Mylopoulos M, Leblanc VR. Clinical supervision and learning opportunities during simulated acute care scenarios. Med Educ 2014;48:820-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramani S, Leinster S. AMEE Guide no.34: Teaching in the clinical environment. Med Teach 2008;30:347-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi S, Mirza R, Nissim R, et al. Internal Medicine Residents' Beliefs, Attitudes, and Experiences Relating to Palliative Care: A Qualitative Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34:366-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ury WA, Berkman CS, Weber CM, et al. Assessing medical students' training in end-of-life communication: a survey of interns at one urban teaching hospital. Acad Med 2003;78:530-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kogan JR, Hatala R, Hauer KE, et al. Guidelines: The do's, don'ts and don't knows of direct observation of clinical skills in medical education. Perspect Med Educ 2017;6:286-305. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piquette D, Moulton CA, LeBlanc VR. Balancing care and teaching during clinical activities: 2 contexts, 2 strategies. J Crit Care 2015;30:678-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones WS, Hanson JL, Longacre JL. An intentional modeling process to teach professional behavior: students' clinical observations of preceptors. Teach Learn Med 2004;16:264-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wear D, Varley JD. Rituals of verification: The role of simulation in developing and evaluating empathic communication. Patient Educ Couns 2008;71:153-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]