A multidisciplinary approach in providing transitional care for patients with advanced cancer

Introduction

According to the American Cancer Society [2014], over 1.6 million people will be diagnosed with a malignancy in 2014. Additionally, an estimated 500,000 Americans are likely to die from a malignancy this year (1). A diagnosis of an advanced or metastatic malignancy is life limiting. This population inevitably has concerns regarding symptom burden, physical and psychosocial impact on life, and questions surrounding end-of-life care. As the illness progresses and care needs become increasingly complex, achieving high-quality whole-person care often necessitates care in multiple settings (e.g., inpatient hospitalization, outpatient clinic, and home-based care). Each transition of care is often met with anxiety and frustration for patients and families as the process of building rapport and developing a sense of security with a new care team is onerous with each change. Inherent to its multidisciplinary nature and ability to provide care in multiple settings, palliative care providers meet patients and families where their care needs require them to receive treatment. Many team members practice in multiple settings (e.g., both in- and out-patient) reducing the number of transitions of care. This integrated care model may lead to a heightened sense of comfort for these patients and families in addition to more timely access to care and improved coordination of care across settings.

With the primary goal of improving quality of life through symptom management, psychosocial support, and assistance with decision-making to align with goals of care, palliative care is an essential part of the care team for these individuals and families (2). Moreover, the central tenets of palliative care include both multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches to whole-person care. To reiterate, providing care in multiple settings may allow for a deeper understanding of patient and family needs. These needs can be communicated directly to the primary oncology team and demonstrates how palliative care can be an ideal model for providing care through the many transitions that are inherent to a life-limiting illness. The case that follows illustrates the benefit of a team-based approach in providing holistic care for persons and families with advanced malignancy across multiple settings.

Case

George is a 68-year-old accountant who was diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer to bone and brain. His illness has progressed through chemotherapy and radiation treatment. One day, while receiving chemotherapy, his bedside nurse noticed that he had difficulty with transfers and experienced grimacing with movement. Palliative care was consulted for assistance with pain and symptom management. Much of the initial consultation with the palliative care team focused on addressing George’s symptom burden and building rapport. George reported “horrible pain” across his anterior chest at the site of his metastasis. He reported taking “leftover” low-dose opioids that had been prescribed for a dental procedure eight months earlier, without adequate analgesic effect. Additionally, his abdomen was distended, tender, and he had not had a bowel movement in over one week. Upon further discussion, the palliative care clinician identified a misconception; George concealed his pain from his primary oncology team because he felt that “poorly controlled pain” would preclude him from receiving further chemotherapy. The palliative care clinician invited the primary oncologist into the conversation so that both clinicians could provide clarification regarding George’s misconceptions pertaining to pain management and access to treatment. His pain was well managed for some time thereafter.

When George’s opioids and adjuvant medications were no longer providing acceptable analgesia, consultation was sought from the interventional pain service to identify modalities that could help him to achieve better symptom control. He received a nerve block that allowed him to be more functional. This allowed him to attend his grandson’s graduation, which was something George had been looking forward to for quite some time. Over time, his conversations with the palliative care team opened the door to deeper conversations regarding hopes and concerns, which prompted additional support from the team’s social worker and chaplain. The team’s pharmacist played an integral role in George’s care both through providing education regarding prescribed medications and liaising with his community pharmacist to allow for easier transitions of care. Finally, the physician and clinical nurse specialist (CNS) played a pivotal role in providing patient-centered care to George and his family across multiple settings.

The palliative care team was able to build a strong rapport with George and his family over time, as a result of collaborating with his care team early in the illness trajectory. The team identified that George’s care needs at home were not sufficiently being met with available services and, based on prior conversations, the team identified that his quality of life was not acceptable—as defined by the patient. A family meeting was arranged and attended by George, his family, and both his oncology and palliative care teams. The entire team assisted in facilitating a smooth transition from home to inpatient hospice care where George died peacefully surrounded by his family months later.

Palliative care team

A palliative care team is a comprehensive group of specialized clinicians from a variety of disciplines who share a common goal to improve the quality of life for patients and families facing serious illness. A consensus panel from the center to advance palliative care (3) describes the following core components to palliative intervention: (I) pain and symptom management; (II) social/spiritual assessment; (III) understanding of illness/prognosis and treatment options; (IV) identification of patient-centered goals of care; and (V) transition of care post-discharge. It seems likely that a multidisciplinary team-based approach is better equipped, than any one clinician alone, in creating an environment to address all components of care for seriously ill patients. Furthermore, patients with advanced cancer experience many transitions of care both in terms of goals of care (e.g., curative vs. comfort-based treatment) and setting of care (e.g., acute care hospital vs. home vs. inpatient palliative care or hospice unit). Many palliative care teams work in multiple settings; thus making the team-based approach to care ideal to assist in making these transitions seamless. Although the composition will vary by institution, many palliative care teams include the following members as part of their core team: the patient and his/her family, physician, advanced practice nurse (APN), nurse, social worker, chaplain, pharmacist, allied health clinician, and complementary therapist. Some of these roles will be reviewed below.

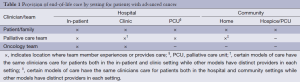

Palliative care physicians and APNs have specialized training in advanced communication skills and treatment of complex symptom management. This skill set provides for effective assessment of “total pain” which includes physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. Patients typically cannot begin to define quality of life for themselves until physical pain is well controlled. Palliative care specialist physicians and APNs are well positioned to achieve optimal analgesia due to nationally accredited training programs that teach evidence-based approaches to control complex symptom burden through medication and interventional management (4). These clinicians are pivotal in providing this holistic care between various settings. Often, transfers between care settings lead to suboptimal care due to loss of information or miscommunication. In our clinical model (a clinical model based in an academic teaching hospital in an urban community setting in Toronto, Canada), physicians provide care to their patients in both hospital (ambulatory clinic, in-patient consultation, and primary attending physician) and community settings (home hospice) (Table 1). Patients can be followed by our palliative care team from a diagnosis of stage IV cancer and receive end of life care in their home as well. Consequently, it is more likely that the transition between care settings will be seamless and in our experience both the patient and family feel very well supported in having this continuity of care.

Full table

The APN and bedside nurse spend the majority of his/her time in direct patient care. As such, the APN and nurse on the palliative care team are well positioned to assist other team members to better understand the patient and family unit, allowing for open communication regarding patient/family needs with multiple team members. Additionally, education is integral to the role of the APN in palliative care. In addition to the development and implementation of formal educational programs and informal bedside teaching, the APN may also provide support for clinicians caring for persons with advanced illness (5). In our experience, when bedside nurses receive tailored teaching and support regarding a focused approach to patient care, the nurse has increased understanding and confidence with respect to the delivery of a comfort-based approach to care.

In our clinical model both physicians and the APN care for patients in multiple settings. However, physicians are based in the hospital while the APN primarily works in the community. The APN is able to establish a trusting supportive relationship with the patient and family by reinforcing how palliative care supports can optimize quality of life in multiple care settings. The APN is also able to identify patients that may benefit from admission to the hospital for symptom management. When patients are admitted to our hospital they repeatedly report feeling comforted when both their palliative care physician and home-based APN are part of their inpatient care team. We argue this is partly due to trust that is built over time, which is essential to providing high quality end of life care. Working together with other specialists and allied health providers, the APN and physician are kept informed of changes to the care plan, lending to smooth transitions back into the community or hospice care at discharge. This is further illustrated through a growing literature base describing further benefits including decreased emergency room visits, fewer hospitalizations and decreased health care costs (6). Social work team members in palliative care integrate expert knowledge of psychosocial supports and assistance with practical matters including finances, housing, and access to services in the community. Specialist level palliative care social workers provide a unique skill set in caring for both patients and families facing life-threatening illness as well as those who are bereaved (7). Further, social work expertise includes patient and family focused communication, attention to environmental influences, and awareness of limitations (8).

Chaplains on the palliative care team provide spiritual support, addressing faith-based questions or concerns that may arise. Chaplaincy team members provide invaluable guidance as spirituality and religious beliefs often affect decision-making and determination of quality of life in individuals with life-limiting illness (9). In-hospital chaplains may also facilitate collaboration with the patient’s community spiritual leader, allowing for a better understanding of the patient/family spiritual needs, which may assist decision making regarding complex goals of care. Regardless of discipline, each clinician on the palliative care team has a common fidelity to the patient. Palliative care clinicians have the ability to listen, remain present, and effectively communicate in the face of much suffering and distress (10).

Oncology collaboration

Providing holistic and patient-centered care for individuals and families facing life-limiting illness cannot be achieved by one specialist or discipline, alone, thus making collaboration with oncology teams imperative to patient care. The benefits of early palliative care involvement for patients with advanced metastatic illness have recently been described (2), and, an integrated model of care, allowing oncologists to focus on cancer-directed treatments and palliative care clinicians to address physical/psychosocial management (11) may soon become the standard of delivering high quality care for this vulnerable population. Several barriers to such collaborations have been identified and include the misperception of palliative care as an alternate philosophy to cancer care, the belief that providing palliative care is part of the oncologist role, and lack of knowledge about institutional and community palliative care services available (12).

Each member of the palliative care team is essential to providing education to collaborative care team members in order to continue with the advancement of this successful care delivery model. Ongoing education is necessary to address commonly held misperceptions that palliative care is a failure of curative care when, in effect, palliative care is appropriate at any stage of illness and can be offered in conjunction with curative treatments. As practice becomes more complex and specialized, it is necessary to educate beyond these misperceptions and create a model of care that is both collaborative and integrative (11).

While many oncologists are well equipped in managing common side effects of anti-neoplastic treatments (i.e., pain, nausea/vomiting, and constipation), collaboration with specialty-trained palliative care clinicians can improve patient care for those patients experiencing complex and difficult to treat symptoms (12). As seen in the case example above, George suffered with pain alone due to a misunderstanding of criteria for access to oncologic treatment. For patients with advanced cancer, a key benefit of palliative care intervention is highlighted by the fact that palliative care teams do not make decisions regarding access to treatment. This may lend itself to creating a less-threatening environment, allowing patients to share pertinent clinical information that they may not feel comfortable sharing with their oncology team who make decisions regarding treatment options.

Patient and family integration

Palliative care places the patient and family at the center of the care team. In order to provide whole-person care the clinician must first understand what is important to the patient and family (4). The definition of family may vary; effective communication with the patient will provide information surrounding important players to his/her defined family. Bringing these members together for important conversations is inherent to effective communication and decision-making in advanced malignancy.

Evidence suggests that many individuals with advanced incurable cancer may not understand that chemotherapy given in this setting aims to reduce symptom burden without curative intent (13). This is not to suggest that oncologists are misinforming their patients when discussing respective treatment options; however, it highlights the complexity of information patients and families must integrate to make informed decisions (14). Active patient participation in care planning has been associated with higher patient satisfaction with care received and with positive clinical outcomes (15). Identifying common misconceptions and using advanced communication techniques to elicit illness understanding and treatment expectations allows palliative care teams to be an asset to the broader interdisciplinary team.

Still, further studies have indicated patients who report better communication from physicians are also at risk for inaccurate expectations, suggesting that patients perceive clinicians to be better communicators when they convey more optimism (13). The palliative care team can act as a non-threatening participant, exploring the patient’s understanding, clarifying treatment options in collaboration with oncology providers, and assisting with decision-making that best align with goals of care. Understanding an individual’s goals, and aligning treatment options to those goals, is central to providing high quality palliative care and can assist oncology teams in optimizing quality of life for their patients.

Summary

Receiving a cancer diagnosis is a life-altering experience; when the illness is diagnosed as advanced or metastatic, it becomes a life-limiting diagnosis. Early identification and involvement with palliative care provides both a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary resource for advanced care planning, supportive care, and expert level symptom management. Collaboration between patient/family, oncology providers, and palliative care can occur concurrently with medical treatments, providing for a team-based approach to advanced malignancies, focused on patient-centered care and quality of life (16). Cancer progression often necessitates care in multiple settings. The case described demonstrates one integrated clinical model of care, illustrating how both interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary teams work in various settings to achieve optimal patient-centered care for individuals with advanced illness. In this delivery model, patients have consistency and familiarity with care providers on the palliative care team. The advantage is that there is increased continuity of care that may lead to more timely access to care and improved coordination of care across settings, which may ultimately result in an optimal integrated care experience for individuals at end of life.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cancer Facts and Figures. United States: American Cancer Society. 2014. Available online: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2014/index

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [PubMed]

- Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2011;14:17-23. [PubMed]

- Doyle D, Hanks GWC, MacDonald N. eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine: 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Skalla KA. Blended Role Advanced Practice Nursing in Palliative Care of the Oncology Patient. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2006;8:155-63.

- Quaglietti S, Blum L. Ellis Vickii. The Role of the Adult Nurse Practitioner in Palliative Care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2004;6:209-14.

- Association of Palliative Care Social Workers. United Kingdom: 2013. Available online: http://www.apcsw.org.uk/role-of-the-palliative-care-social-worker.html

- Sheldon FM. Dimensions of the role of the social worker in palliative care. Palliat Med 2000;14:491-8. [PubMed]

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885-904. [PubMed]

- Ferrell BR, Coyle N. eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing: 3rd edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Bruera E, Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4013-7. [PubMed]

- Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, et al. Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. J Oncol Pract 2014;10:e37-44. [PubMed]

- Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616-25. [PubMed]

- Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, et al. The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: a communication guide. J Palliat Med 2013;16:894-900. [PubMed]

- Keating NL, Beth Landrum M, Arora NK, et al. Cancer patients’ roles in treatment decisions: do characteristics of the decision influence roles? J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4364-70. [PubMed]

- Morrison RS, Meier DE. Clinical practice. Palliative care. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2582-90. [PubMed]