The global state of palliative care—progress and challenges in cancer care

Introduction

The evolving demographics and epidemiology of life-limiting diseases across the world have created an urgent and growing need for palliative care development (1). The integration of palliative care with mainstream health care across the globe has grown in recent years (2,3). However, in one third of the world there is no access to palliative care for persons with serious or terminal illness.

Each year an estimated 6.5 million persons with cancer will need end-of-life palliative care (3,4). These individuals have a basic human right to palliative care services to reduce suffering, promote quality of life, allow death with dignity, and to support caregivers (5-7).

The most pressing challenges to overcome in global palliative care are: to adopt a common definition of palliative care, to integrate palliative care with basic health care as part of both curative and non-curative models, to garner funding and engagement from international partnerships, governmental health ministries and non-governmental organizations (NGO), to standardize and coordinate palliative care services, to educate health care providers, and to improve access to opioid pain-relieving medicines (1-3,6-12).

International and national groups, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Palliative Care Alliance (WPCA) promote activism, monitor progress, and provide resources on education and policy to countries developing palliative care (3,11-14). These palliative care entities have declared a call to action and international collaboration to advance the global status of palliative care (3,6,7). In this article, the authors will review overall progress in palliative care development and explore some of the barriers influencing cancer care across the globe.

Defining palliative care

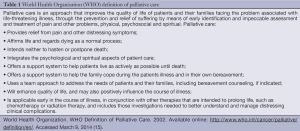

The WHO definition of palliative care is a “response to suffering” (see Table 1) that includes physical, psychological, social, legal, and spiritual domains of care and is provided by an interdisciplinary team of professional and lay health care providers (13,15). The WPCA recommends that all governments and NGOs adopt this definition and employ it as a template to build national health care policies and educational initiatives in palliative care.

Full table

Palliative care delivery models serve patients and families in patients’ homes, medical facilities, hospice units, and outpatient settings (3,13). The availability and palliative care training of caregivers varies by region of the world and its resources. The countries with higher Human Development Index (life expectancy, education level, and economic status) and higher gross domestic product report greater palliative care integration with health care (2,11,14,16,17).

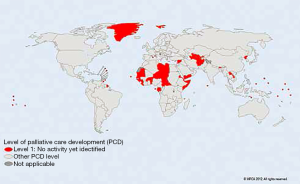

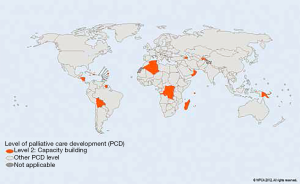

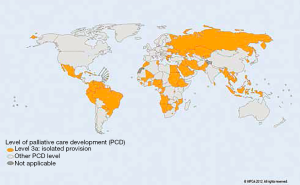

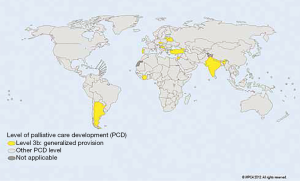

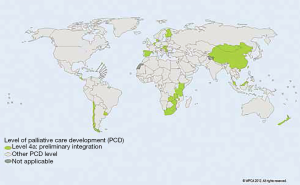

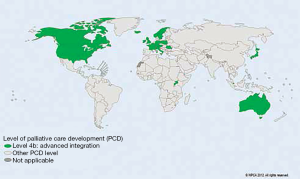

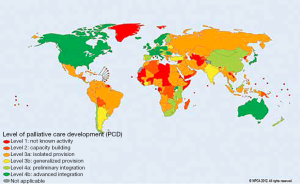

In 2011, the WPCA updated a global inventory of hospice and palliative care development in the world’s 234 countries derived from diverse literature sources, hospice directories, and opinion leaders (2,3). This methodology incorporated multiple factors including palliative care delivery models, access to pain-relieving drugs, such as morphine, level of awareness and activism in the health care and policy communities, and the presence of centers for education and professional association. Each country was assigned to one of six categories (Figures 1-7 copied with permission) (3):

- Group 1: no known hospice-palliative care activity;

- Group 2: capacity-building activity;

- Group 3a: isolated palliative care provision;

- Group 3b: generalized palliative care provision;

- Group 4a: hospice-palliative care services available at initial stage of integration with existing health care services;

- Group 4b: hospice-palliative care services with comprehensive and progressive health care integration.

In summary, there is some degree of hospice-palliative care development in 136 (58%) of countries. Advanced integration (group 4b) is reported in 45 (19%) countries, while 75 (32%) countries are without access to palliative care (group 1). Since 2006, modest advances in palliative care activities are evident, most notably in Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas/Caribbean countries (3).

Global need for palliative care in cancer

The need for palliative care is expanding due to the aging of the world’s population and the increase in the rate of cancer in both developed and developing countries. It is difficult to measure the scope of need for palliative care with existing research methodologies (3,18). Most estimates are based on death rates, which do not include numbers of person suffering earlier in the illness course (3). Collection of accurate numbers of service agencies and providers is another challenge to this research. Loucka et al. (18) compared major research projects aimed to characterize the global status of palliative care. They found worrisome limitations in the theoretical framework, information sources, and consistency of ranking systems.

The WHO estimates that each year 20 million people need palliative care at the end of life, 67% among older adults (60 years of age or older), and 6% among children (1,3). Cardiovascular disease-related deaths comprise over 38% of deaths, cancer causes 34%, and chronic respiratory conditions are responsible for 10.3% of deaths. Worldwide, HIV/AIDS accounts for 5.7% of deaths; although in African nations its impact overshadows cancer (3).

In the world’s most populous nations, China and India, palliative care development has advanced from localized service provision to some preliminary integration with the health care system. However, large disparities in access to both curative and palliative medicine exist that are based on socioeconomic status (19).

The rate of cancer among adults is increasing worldwide, most significantly in European and Western Pacific regions that include higher income, developed countries where longevity and lifestyle factors such as smoking, and physical activity levels affect cancer risk (3,4,20). In less economically advantaged countries with expanding populations, cancer incidence and death rates are also rising. In these regions fewer cancer prevention and screening services exist which may explain why as many as 80% of patients are diagnosed in advanced stages of illness. In countries with gaps in basic health care services, the rationale for blending palliative care into the continuum of public health is even stronger (1,4).

Among cancer patients, approximately 80% need terminal palliative care (12). If family and caregivers are also considered within the unit of care, the need increases 2 to 3 folds (3). Children with the greatest need for oncology palliative care come from Eastern Mediterranean, African, South East Asia, and Western Pacific regions (3).

Palliative care is a human right

In 2000, the International Covenant of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights issued a statement that signatory nations’ core obligation was to ensure health care to all individuals, to supply adequate medicines, to develop and oversee policies for public health (3,5). Since palliative care is integral to health, it is, therefore, a fundamental human right. This view is endorsed by international organizations including WHO, the International Working Group, WPCA, and the National Hospice and Palliative Care Associations (1,3-7,13). Further support for this notion came in 2006 from Pope Benedict XVI who equated palliative care with “the preservation of human dignity” and defended the provision of care to the sick as a human right (5).

At the 2011 European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) congress palliative care advocates published the Lisbon Challenge (7). This call to action charged governments to develop health policies to address needs of patients with serious illnesses, eliminate restrictions to opioids and other essential comfort medicines, provide adequate training of health care workers in palliative care across disciplines, and design sustainable palliative care programs sized to the needs of their national population. In 2014, the WPCA’s Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life declared palliative care as a human right (3).

The Prague Charter represents the collective advocacy of international palliative care and human rights organizations to demand changes in attitudes, government policies and resources, and health care worker training to ensure the right to palliative care (6).

Benefits of palliative care in cancer care

Comprehensive cancer care that includes the four pillars: primary prevention, early detection, curative treatment, and palliative care is not universally accessible (4,20). Indeed, cancer is the leading cause of death in the world (12). Its greatest impact is evident in countries with limited cancer prevention, screening, and treatment services. These are countries where lower income and disadvantaged populations have high exposure to carcinogens, lifestyle and occupational factors, and less health education to counter these risks or advocate for health care change. Persons with cancer are more apt to present when the disease is far advanced and incurable (4,12,20). Ninety percent of these patients will die with limited or no services for palliation.

Palliative care ameliorates symptoms, most frequently, pain, and reduces use of health care services not beneficial for quality of life or longevity, especially in the terminal disease phase (1,4). While research findings supporting the benefits of palliative care originate from countries with more plentiful health care resources, evidence is growing that models of care delivery scaled to different cultures show similar results (1).

In more developed countries, an effort to integrate palliative care into primary care and specialty oncologic practice is ongoing (4,20,21). Philosophically, this integration reflects the growing acceptance that all patients have a right to palliation regardless of goals of the cancer therapy (1,3,4). Therefore, primary or generalist health providers as well as cancer care specialists need skills to manage basic symptom issues and respond to psychosocial and spiritual concerns (22). These “primary palliative care” responsibilities are distinguished from those expected of trained palliative care specialists. The latter can manage the most complicated issues in either the biomedical or psychosocial domains (22).

Blending palliative care into routine oncologic care is also a pragmatic response to workforce issues (22). In the USA, for example, in 2013 there were 5,000 palliative care providers trained at the specialty level (22). Therefore, oncology providers must acquire primary palliative care skills in the symptom management, psychosocial, and spiritual domains.

In the foreseeable future the demographics of aging in the USA and worldwide will create a growing mismatch between numbers of trained providers and individuals needing palliative care. For refractory cases, consultation with a specialty-trained provider will be necessary where available. However, patients will maintain their primary relationship with the oncology provider.

Barriers to palliative care development

Overcoming barriers to palliative care is a major global health agenda item (1,3,6,7,20,21). Two of the most pressing aforementioned issues are the need for health care worker education in palliative care and patient access to essential palliative medicines.

Education of health care providers in palliative care

The Prague Charter called for government action to adapt curricula for all health care workers, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, mental health providers, and others to include basic palliative care content (6). A first step is to increase awareness of this deficit among the public and health care community (1). In many countries professional literature about palliative care is scarce or non-existent (10). In a large survey of Western European countries, palliative care was an unknown concept, or was considered merely an attitude of caring rather than as a distinct specialty or skill set (10).

There are three main categories of palliative care expertise that include: (I) basic palliative care training requisite for all providers; (II) intermediate level of training for front line providers who routinely care for patients with life-limiting illnesses, for example, oncology; and (III) specialty-level practitioners or teams capable of managing complex, refractory symptoms and advanced communication (1,3,22). In Western Europe, a large scale survey identified gaps in availability of basic and specialty level training programs at undergraduate and post-graduate levels (10).

A survey of European countries that train and recognize specialty or subspecialty status in palliative medicine reported that only Ireland and the United Kingdom award full specialization (11). Five other countries acknowledge subspecialty status in palliative medicine, and in nine European countries specialty recognition is in discussion. In the USA, physicians with specialization in eleven different medical specialties can pursue hospice and palliative medicine fellowships towards sub-specialty certification (11).

Medical professionals’ singular focus on curing disease presents another attitudinal barrier limiting palliative care development (10,20). If death from cancer is considered a medical failure, energies to improve end-of-life care will remain a secondary priority. Lack of designation of specialty knowledge base or specialty certification will limit aspiring health care professionals from choosing a palliative care career and curtail the future supply of palliative care professionals.

Opioid analgesia

Pain management is an integral concept in the practice of palliative care. Unfortunately, pain spans ages and all medical specialities (23). Lack of proper pain medication affects not only the patient, but also the family and friends witnessing the patient’s suffering. The WHO estimates that in 80% of the world population there is insufficient access to appropriate opioid analgesics (3). Therefore, throughout the world patients who require aggressive pain management face barriers to relief of such suffering.

A variety of prescription analgesics are available to those experiencing pain including NSAIDs, corticosteroids, opioids, and non-opioids adjuvants. Experts agree that opioids are necessary for cancer pain relief (24). Furthermore, opioids are affordable and safe (4,23). In fact, morphine in its variety of formulations is listed on the WHO list of essential medicines (25).

As the population ages, the number of those with chronic and terminal illnesses will increase, as will the need for adequate pain control with opioid analgesics (23). According to WHO, “All countries have a dual obligation with regard to (opioids) based on legal, political, public health and moral grounds. The dual obligation is to ensure that these substances are available for medical purposes and to protect populations against abuse and dependence” (26). Still, barriers to availability of opioids prevail including fear of addiction, lack of education for providers, and difficulties related to procurement, manufacture and distribution (27).

Worldwide availability and accessibility of opioids

An argument can be made that the first step to expand global palliative care is to ensure adequate pain relief, which cannot be achieved without access to the appropriate analgesics. Many acknowledge the global lack of necessary access to opioids (24,27,28). It has even been labeled as a “pandemic” (29).

At the 67th World Health Assembly, national leaders strongly advocated for an improvement in the availability and accessibility of opioids globally (1). Nevertheless, stark disparities in global access remain (4,23). For instance, only 7.5% of the world population (compromising countries all located in the WHO American and European Regions) have adequate consumption levels of opioids (23).

Moreover, 83% of the world population living in low- and middle-income countries consumed only 9% of the total global morphine available (30). A study of opioid availability in 25 African countries (total =52) found that only three of the countries had immediate-release oral morphine always available (31).

Seya et al. (30) conclude that to achieve an adequate opioid supply would require at least six times the existing amount of morphine equivalents (30). In other words, the calculated production consumption of morphine equivalents in 2010 was 290 metric tons, while for projected adequate consumption of morphine worldwide 1,448 metric tons would need to be produced. Thus, with only a fifth of the amount of opioids available, the majority of people experiencing pain will not receive necessary opioids (23).

Availability and accessibility of opioids has been called a “human right” (3,5-7). However, fears coupled with misperceptions inhibit this right. “The fear of diversion, abuse, and dependence are the main reasons why countries limit access to opioid analgesics, but the measures taken often do not address the problem, but, instead, negatively affect patients’ access for legitimate purposes” (9). Restrictions and barriers to accessibility hamper goals of achieving patient comfort (23).

Regulatory restrictions on opioids

Regulations vary greatly among nations and directly influence accessibility to opioid analgesics. Certain restrictions may undermine availability (4,28,31). Regulatory restrictions influence healthcare professionals and lay people alike by focusing on the dual nature of opioids (23,24,32) and the use of legal intimidation (29). Some policies are even contradictory (27).

Current regulatory barriers as examined by the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) and the European Society for Medical Oncology and the EAPC (ESMO/EAPC) Opioid Initiative Policy include: requirement for permission/registration of a patient to render them eligible to receive opioid prescriptions, requirement for physicians and other clinicians to receive special authority/license to prescribe opioids, requirement for duplicate prescriptions and special prescription forms, prescription limits, dose limits, limitations on dispensing privileges, provision of opioid prescribing in emergency situations, pharmacist privilege to correct technical errors on a prescription, use of stigmatizing language, and unreasonably severe penalties for inadequate record-keeping (4,24,27,31).

Clearly, providers may be deterred from prescribing opioids due to the arduous details involved (29). For example, ten African countries do not allow physicians to prescribe an amount of opioid analgesics to a patient for more than 2 weeks at a time and in Ghana doses are limited to 2 days (31). Similarly, in Ukraine providers are only permitted to write a 1 day supply of opioids (24). Another instance of this can be found in certain European (Latvia, Estonia, Albania, and Denmark) and African countries (Mauritius, Morocco, Sierra Leone, and Tunisia) where physicians must purchase special prescription forms (24,31).

Regulatory barriers also affect patients’ access to opioids. In the country of Georgia, opioids are only dispensed to patients via select pharmacies located in police stations (24). Many countries require patient registration to receive opioids, some African and European countries even require special registration for hospice patients (24,31). Logistical barriers such as the aforementioned influence patient and family attitudes related to opioids.

Scholars have called for change in policy (24,26,28,29,31,32). Excessive regulations may not only cause undue suffering in patients, but also cause distress in families and health care professionals (29). Indeed, opioid regulation should favor a “public health model” to improve care rather than represent a “criminalization model” to prevent diversion of opioids, although this is not always apparent (24). A study of 41 European countries identified the following correlation, “the countries with the most limited opioid formularies tended also to have the greatest number of regulatory barriers to accessibility” (24). In order to enact change, each country and their individual government must accept the responsibility to improve access to opioids (28).

Provider barriers to proper opioid use

Provider barriers include opioid availability, specific limits related to prescribing, use of stigmatizing language, and lack of proper education/training. Opioid availability and prescribing limits are described above. The use of stigmatizing language may avert potential prescribers. In a review of opioid regulations for 41 European countries, 2 included the pejorative term, “poison” to describe opioids, 10 referred to them as “drugs of addiction”, and 4 use the term “dangerous drugs” (24). With such language, it is no wonder that opioiphobia, or fear opioids, exists.

Inasmuch as regulatory barriers influence availability to opioids and therefore pain management and palliative care, providers’ knowledge and attitudes directly affect patients’ access to pain control. One survey of Nigerian medical providers found that for almost 60% pain assessment of oncology patients is not routine (33). Additionally, over 10% of respondents did not support pain relief for this population (33).

Patients fear that pain will be uncontrolled, especially at the end-of-life. A survey of the Nambian public found that pain at the end-of-life is the most concerning symptom for most people (34). Healthcare professionals have an imperative to adequately and appropriately treat pain. To achieve this there must first be a change in attitudes (4,23,32). Once providers are open to treating pain, they must be properly educated to manage pain.

State of education and efforts

The need for increased education among healthcare professionals and the public has been aptly recognized (1,4,23,27,29,32,33). Opioiphobia is rampant among healthcare professionals and lay people (31,33,35). In Ghana, patients and health care professionals alike fear opioids and addiction due to limited understanding. There is a fear amongst the people of Ghana that opioids symbolize the end-of-life (35). Widespread opioiphobia has led to resistance to properly treat pain and consequently influences pharmacies to limit supply of opioids available (35).

Among teaching hospital physicians in Nigeria, more than half of those surveyed admitted lack of knowledge of cancer pain management and 91.5% of practitioners received no formal education in pain management (33). Another study of 120 oncology fellows found that less than 50% were able to choose the appropriate interval for opioid breakthrough dosing. Further results of this study revealed that only 31% of the fellows correctly solved a simple opioid conversion (36).

To enact change, the unique need of each country must be explored. The International Pain Policy Fellowship is one example of how improvements in opioid accessibility have been achieved (32). A fellow in Serbia (population 7.5 million) distributed educational brochures on opioiphobia and published a translation of the textbook Pharmacotherapy of Cancer Pain in Serbian (32). After implementing an action, the fellow helped register oral morphine for the first time in Serbia in 2008 with the International Pain Policy Fellowship efforts (32).

WHO has created the Access to Controlled Medications Programme (ACMP) to address some of these issues (26). With a budget of $55.5 million over six years, two-thirds of which will target improving access to opioids, the ACMP is the first global initiative of this kind (26). This effort will require global change. Cleary calls for multidimensional change “the cornerstone trinity”, i.e., medication availability, education, and policy reform (28). This trifecta is echoed by others (31). Still others insist that cultural change with a stronger focus on the necessity of palliative care and pain relief is key (29).

Conclusions

Global progress in developing palliative care across the world is in flux. While progress in the last 5 years is encouraging, millions of individuals with cancer and their families suffer unnecessarily during cancer treatment and at the end-of-life. International palliative care professionals and advocates continue to argue for the rights of patients to palliative care, for the removal of barriers to access to services and palliative medicines, engagement of health care ministries, professional resources and education. The evolving demographics of the world’s population growth and its predicted impact on cancer statistics constitute a worldwide public health emergency.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment within the continuum of care. Available online: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB134/B134_R7-en.pdf. Accessed 4/13, 2014.

- Lynch T, Clark D, Connor S. Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global update 2011. Available online: . Accessed 4/13, 2014.

- Connor S, Sepulveda C. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End-of-Life. 2014. Available online: http://www.thewpca.org/resources/global-atlas-of-palliative-care/

- Currow DC, Wheeler JL, Abernethy AP. International perspective: outcomes of palliative oncology. Semin Oncol 2011;38:343-50. [PubMed]

- Brennan F. Palliative care as an international human right. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:494-9. [PubMed]

- Radbruch L, de Lima L, Lohmann D, et al. The Prague Charter: urging governments to relieve suffering and ensure the right to palliative care. Palliat Med 2013;27:101-2. [PubMed]

- Radbruch L, Payne S, de Lima L, et al. The Lisbon Challenge: acknowledging palliative care as a human right. J Palliat Med 2013;16:301-4. [PubMed]

- Callaway M, Foley KM, De Lima L, et al. Funding for palliative care programs in developing countries. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:509-13. [PubMed]

- Praill D, Pahl N. The worldwide palliative care alliance: networking national associations. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:506-8. [PubMed]

- Lynch T, Clark D, Centeno C, et al. Barriers to the development of palliative care in Western Europe. Palliat Med 2010;24:812-9. [PubMed]

- Clark D. International progress in creating palliative medicine as a specialized discipline. In: Hanks G, Cherny NI, Christakis NA, et al. eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010:9-22.

- World Health Organization. Cancer control: Palliative care. WHO guide for effective programmes. 2007. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/publications/cancer_control_palliative/en/. Accessed 4/13, 2014.

- Gwythere L, Krakauer E. WPCA policy statement on defining palliative care. 2011. Available online: http://www.thewpca.org/resources/?WPCA%20policy%20defining%20palliative%20care. Accessed 4/13, 2104.

- Clark D, Wright M. The international observatory on end of life care: a global view of palliative care development. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:542-6. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Definition of palliative care. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed 3/9, 2014.

- Wright M, Wood J, Lynch T, et al. Mapping levels of palliative care development: a global view. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:469-85. [PubMed]

- United Nations. Human development index (HDI). Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/hdi. Accessed 4/14, 2014

- Loucka M, Payne S, Brearley S, et al. How to measure the international development of palliative care? A critique and discussion of current approaches. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:154-65. [PubMed]

- Rajagopol MR, Twycross R. Providing palliative care in resource-poor countries. In: Hanks G, Cherny NI, Christakis NA, et al. eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010:23-31.

- Von Roenn JH. Palliative care and the cancer patient: current state and state of the art. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011;33 Suppl 2:S87-9. [PubMed]

- Rocque GB, Cleary JF. Palliative care reduces morbidity and mortality in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:80-9. [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173-5. [PubMed]

- Duthey B, Scholten W. Adequacy of opioid analgesic consumption at country, global, and regional levels in 2010, its relationship with development level, and changes compared with 2006. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:283-97. [PubMed]

- Cherny NI, Baselga J, de Conno F, et al. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Europe: a report from the ESMO/EAPC Opioid Policy Initiative. Ann Oncol 2010;21:615-26. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Model list of essential medicines. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/93142/1/EML_18_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 4/14, 2014.

- Scholten W. Access to controlled medications programme. Available online: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/ACMP_BrNote_Genrl_EN_Apr2012.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 4/14, 2014.

- Husain SA, Brown MS, Maurer MA. Do national drug control laws ensure the availability of opioids for medical and scientific purposes? Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:108-16. [PubMed]

- Cleary J, Radbruch L, Torode J, et al. Next steps in access and availability of opioids for the treatment of cancer pain: reaching the tipping point? Ann Oncol 2013;24 Suppl 11:xi60-4. [PubMed]

- Cherny NI, Cleary J, Scholten W, et al. The Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) project to evaluate the availability and accessibility of opioids for the management of cancer pain in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East: introduction and methodology. Ann Oncol 2013;24 Suppl 11:xi7-13. [PubMed]

- Seya MJ, Gelders SF, Achara OU, et al. A first comparison between the consumption of and the need for opioid analgesics at country, regional, and global levels. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2011;25:6-18. [PubMed]

- Cleary J, Powell RA, Munene G, et al. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Africa: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI). Ann Oncol 2013;24 Suppl 11:xi14-23. [PubMed]

- Bosnjak S, Maurer MA, Ryan KM, et al. Improving the availability and accessibility of opioids for the treatment of pain: the International Pain Policy Fellowship. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1239-47. [PubMed]

- Ogboli-Nwasor E, Makama J, Yusufu L. Evaluation of knowledge of cancer pain management among medical practitioners in a low-resource setting. J Pain Res 2013;6:71-7. [PubMed]

- Powell RA, Namisango E, Gikaara N, et al. Public priorities and preferences for end-of-life care in Namibia. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:620-30. [PubMed]

- Fisch MJ. Palliative care education in Ghana: reflections on teaching in West Africa. J Support Oncol 2011;9:134-5. [PubMed]

- Buss MK, Lessen DS, Sullivan AM, et al. A study of oncology fellows’ training in end-of-life care. J Support Oncol 2007;5:237-42. [PubMed]