Spirituality, religion and palliative care

Introduction

There is no doubt that the American population is aging; life expectancy has increased and, in turn, more people are living longer and sicker. By the year 2030, 70 million Americans will reach the age of 65 (1). Medicare expenditures will reach $835 million dollars by 2016; a large portion of these expenditures are spent within the last 2 years of life (2-4), a fact many clinicians can attest to as they care for chronically ill patients.

As medical science has evolved, many conditions that were once considered “death sentences” have become chronic conditions that require long-term medical intervention and management. In many ways this makes end of life care more complicated, fraught with decisions about what interventions are appropriate and when to withhold or withdraw care.

The process of dying, once thought an art, has now become a science. In Western Europe and North America, until the 19th century, caring for the dying and the bereaved was seen primarily as the job of the family and the church. The culture of death changed dramatically during the 20th century. With the advances in medical science, death is seen less as a natural part of life and more as something to be kept at bay for as long as possible. Death and dying have shifted from the home and community to institutional settings, and medical personnel have now become the sentinels. Death and all that surrounds it has become more of a biomedical process, explained through a series of physiologic events. If we fail to look at the emotional, social, psychological and spiritual components of death and end of life, we have truly missed the boat on providing whole-person care (5-7).

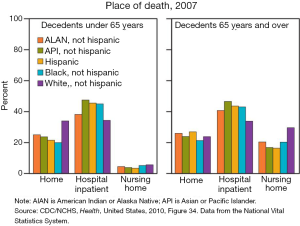

As delivery models of health care have evolved, conversations about preferences and goals at end of life have become more culturally acceptable. According to data collected by the CDC, there are many factors that play a part in the place of death. These factors include individual preferences, cultural beliefs, access to care, age, social support, and race and ethnicity. When surveyed, the majority of Americans state that their preference is to die at home, yet for many this goal is not met and end of life care is provided in an institution. Over the past 25 years there has been a shift in where people spend their last days. While 23% to 36% of Americans die in institutions such as a hospital or nursing home, data shows that in 2007 approximately 25% of all deaths occurred at home, increased from 16% and 22% in 1989 and 1997 respectively (8) (Figure 1).

Biopsychosocial-spiritual model

The biopsychosocial model has become more widely accepted as a framework for understanding the needs of patients and their families, more so than the traditional pathophysical and biological/disease-process approach. Within this model, illness is viewed within the context of the complex interplay of biological, social, psychological and spiritual factors that frame an individual’s response. This model recognizes that for one to provide effective health care, consideration has to be given to relationships—the patient’s relationship with self and others within their immediate circle as well as relationships within the larger community. Consideration also has to be given to the clinician’s relationship with the patient. All of these things, when seen as a whole, help to tell the unique story of each patient. It helps to create a narrative for their response to and understanding of their illness (9-11).

Recognizing the need for whole person, patient and family centered care, the medical establishment has become reasonably adept at addressing the biological, social and psychological factors that are at play in a patient’s experience of serious illness. We have become accustomed to a multidisciplinary model of care, relying on the knowledge and expertise of our psychiatry, social work and case management colleagues to help us navigate areas with which we are less familiar. It should be no less so with regard to spiritual care. As with other dimensions of whole-person care, there is a reasonable expectation that providers have at least basic language to assess the spiritual needs of a patient. For many with serious or life-threatening illness, this is when spiritual needs are the greatest (11-13).

In the Coping with Cancer Study, 230 patients with a diagnosis of advanced cancer and prognosis of less than 1 year were interviewed. Patients rated the importance of religion to them and their attendance at religious services or private religious activities such as prayer before and after their cancer diagnosis. They also rated the amount and quality of spiritual support received from the medical system as well as their own religious community. Of these patients, 68% identified that religion was very important, 20% found it somewhat important and the remaining 12% found it was not important. Eighty-nine percent of African-Americans, 79% of Hispanics and 59% of Whites noted religion to be very important. Increased religiousness was associated with increased patient distress at the time of the study. Additionally, the study noted that private daily religious activities such as prayer and meditation increased from 47% before diagnosis to 61% after diagnosis. This study clearly highlights the importance of spirituality and religion to patients struggling with serious illness (14).

The importance of spirituality, religion and culture in the lives of our patients cannot be overlooked. These factors serve as key components to build the framework by which patients guide decision-making during illness and at the end of life. Many patients share that spirituality helps them to find meaning in their illness. Conversely, spiritual concerns can be a source of distress for patients if they see their illness as punishment for a life poorly lived. The role of religion goes beyond here and extends to a place where patients rely on religious practices or spiritual beliefs to guide their choices about end of life care. Despite this knowledge on the part of clinicians, patients often identify that their spiritual needs are not adequately met, and that spirituality is not discussed as openly as they wish (14-17).

Spirituality and religion defined

The terms spirituality and religiosity are often used interchangeably but are distinct in many ways. Religion can be defined as “the service and worship of God, other deities or the supernatural; commitment or devotion to religious faith or observance; a personal set or institutionalized system of religious attitudes, beliefs, and a cause, principle or system of beliefs held to with ardor and faith”. Whereas religion or religiosity refers to a particular set of beliefs and tenets held to by its observers, spirituality is somewhat of a less formal state of being, so to speak (18).

There is no set, agreed upon definition for spirituality; definitions seem to vary by discipline. In the nursing literature we find spirituality defined as “that which gives meaning to one’s life and draws one to transcend oneself. Spirituality is a broader concept than religion, although that is one expression of spirituality. Other expressions include prayer, meditation, interactions with others or nature, and relationship with God or a higher power” (18).

Puchalski et al. defines spirituality as “that which allows a person to experience transcendent meaning in life. This is often expressed as a relationship with God, but it can also be about nature, art, music, family, or community—whatever beliefs and values give a person a sense of meaning and purpose in life (19)”.

Spirituality speaks to the idea of a process or journey of self-discovery and of learning not only who you are, but also who you want to be. Spirituality is personal, but it is also rooted in being connected with others and with the world around you; it often embraces the concept of searching and moving forward in the direction of meaning, purpose, and direction for your life (13,15).

Broader definitions of spirituality point to that which helps to give meaning or purpose to one’s life. While spirituality can find its expression in religious observance, it may also be experienced and expressed in the broader context of interpersonal relationships, cultural interactions, or interface with nature. Spirituality is a dynamic, evolving process, one that impacts and is impacted by an individual’s life experience.

In a Gallup poll conducted in January 2002, 50% of American respondents identified themselves as “religious”, while 33% described themselves as “spiritual but not religious”. A further 11% described themselves as neither, and 4% as both. In an earlier Gallup poll done in 1999, approximately one third of respondents defined spirituality without reference to God or other deity/higher authority; descriptions of spirituality included “living the life you find pleasing; a calmness in life; something you put your heart into” (20).

Spiritual distress

Just as pain is at times a difficult experience to describe and quantify, it is no less so with spiritual pain or distress. It is not uncommon to find that those who are experiencing life threatening illness may also experience spiritual distress. As defined by the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, “spiritual distress refers to a disruption in one’s beliefs of value system, a shaking of one’s basic beliefs”. Anandarajah and Hight note that “spiritual distress and spiritual crisis” occur when a person is “unable to find sources of meaning, hope, love, peace, comfort, strength, and connection in life or when conflict occurs between their beliefs and what is happening in their life (21)”.

It is important to recognize issues, symptoms or attitudes expressed by a patient that may point to spiritual distress. Those who question the meaning of life, question where God is during their suffering, see their illness as retribution for a life of poor choices, express anger at God or a higher power may be experiencing spiritual distress. Other symptoms include feeling as if their sense of direction and purpose has been lost, questioning their belief systems or directly seeking spiritual help (13,15,16,22,23).

Dame Cicely Saunders, recognized as the founder of the modern hospice, is credited for introducing the concept of total pain. This idea included the physical, social emotional and spiritual dimensions of distress (Figure 2). Within the field of palliative care, pain is one of the most distressing symptoms patients may experience. There are instances we have all experienced where management of an individual’s pain seems to be more difficult than one would anticipate. In those cases, it is important to ask whether there is more that is contributing to the experience of physical symptoms of distress. Unaddressed spiritual issues may frustrate one’s attempts to treat other symptoms, and have an adverse effect on quality of life. As each dimension is addressed in turn, distressing symptoms may be alleviated (13,22,24,25).

Over the years, numerous studies have established the importance of religion, spirituality and religious coping in the context of serious illness. In a study published in 2000 in the Annals of Medicine, Steinhauser et al. sought to gather descriptions of the components of a good death from patients, families, and providers through focus group discussions and in-depth interviews. Seventy-five participants—70% white and 28% African American; 61% protestant, 18% catholic-including physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, hospice volunteers, patients, and recently bereaved family members—were recruited from a university medical center, a Capitalize Veterans Affairs medical center, and a community hospice. Six themes were identified as consistent with a “good death”, including pain and symptom management, clear decision making, preparation for death, contributing to others, affirmation of the whole person and completion. The concept of completion speaks to resolving conflicts, saying goodbye, spending time with family and friends, and attending to issues of faith (7,11,25,26).

A good death was also seen as one that was free from avoidable distress for patients, families and caregivers, one that is in general accord with patients’ and families’ wishes, reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural and ethical standards, an expectation—the rule and not the exception, and something that is achievable by everyone.

Spirituality and culture in palliative care

As we think about how patients make decisions at end of life, we will have failed if we do not take the time to consider culture. It is hugely important in the context of our work as palliative care providers that we be culturally sensitive and competent. In the broader context, culture is not only determined by ethnicity or race; it is determined or influenced by spirituality/religion, SES, level of education, level of acculturation, gender, age, sexual orientation, country of origin and immigration status. Culture is an important concept to consider as we care for the ill and dying, as an individual’s culture will influence how they make sense of their illness and death, as well as how they make end of life decisions (27).

Culture plays an unmistakably important role in the experience of life-threatening illness. Yet despite one’s cultural background or preferences, there are needs that are universal to all persons experiencing illness. All patients and their family wish to approach end of life with dignity, self-respect and an opportunity for building and securing their legacy. What differs may be how each individual goes about accomplishing these tasks (28,29).

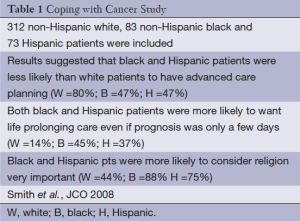

In September of 2008 Smith and colleagues published a study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology: Examining racial and ethnic differences in advanced care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness and treatment preferences (Table 1).

Full table

Terminal illness acknowledgement was assessed using the question “How would you describe your current health status?” Participants responded by choosing “seriously and terminally ill”, “relatively healthy” or “seriously but not terminally ill”.

The importance of religion was assessed using the question “How important is religion to you?” where potential responses were” very important,” “somewhat important” or “not important”. Treatment preferences for end of life were assessed with the question “Would you want the doctors here to do everything to keep you alive even if you were going to die in a few days anyway?” Those who responded yes were considered to want life prolonging care.

Preference for prognostic information was assessed using the question “If your doctor knew how long you had to live would you want him to tell you?” In addition to the results noted above, the study found that compared to white patients, both black and Hispanic patients were less likely to want to be told their prognosis by a physician (black and Hispanic pts 58% and 61% respectively, vs. white pts 77%).

Overall, the findings of this study suggested that “although there were important racial/ethnic differences in terminal illness acknowledgement, religiousness and treatment preferences among patients with advanced cancer, none of these factors accounted for the racial and ethnic differences in advanced care planning” (16).

For many patients who identify spirituality and religiosity as important to their experience and response to illness, they wish for the opportunity to discuss their spiritual challenges with their health care team. Some patients may even see their providers as tools used by God to treat suffering or offer healing. But the ultimate decision on the outcome of an illness is viewed to lie only with God, so if medicine fails, miracles are still possible. Having a clinician who is open to faith and to engaging in spiritual discussions can often serve to put patients at ease, allowing them to explore the challenges they face as they consider their mortality.

Illness is often seen as “God’s will”; acceptance of “God’s will” is often used as a coping strategy—those who saw their illness in this light often believed that God was in full control of the outcome of the situation. Spirituality is often used to help support acceptance of a diagnosis.

Spiritual coping

Balboni and colleagues looked at religious and spiritual support among cancer patients as it relates to associations with end of life treatment preferences and quality of life. In this study, 88% of respondents identified religion and spirituality as factors that were paramount in helping them adjust to their illness. Additionally, prayer, meditation and religious study were highlighted as other factors important in coping with illness. Theories abound that suggest that there is meaning and comfort to be found in religious coping (17).

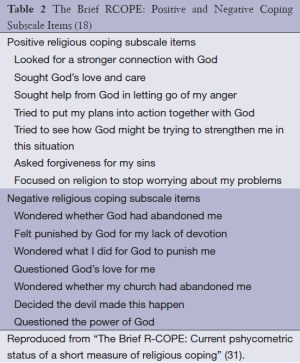

Religious coping is a distinct entity within the framework of spirituality and religion. This concept refers to how patients use their religious beliefs to understand and adapt to life stressors. Positive religious coping employs constructive reliance on faith to make sense of and find meaning in illness, and is widely associated with greater psychosocial adaptation to stressors. Conversely, those who employ negative religious coping may be more likely to view illness as punishment or divine retribution. Though less common, negative religious coping should nonetheless be considered as part of a complete spiritual assessment, as it may point to an existential crisis (29-31) (Table 2).

Pargament et al. undertook a study whose purpose was to develop and validate a tool that would assess the full range of religious coping, including both helpful and harmful religious expressions. The RCOPE was initially tested on a large sample of college students who were experiencing significantly stressful life events. The tool was then administered to a large group of hospitalized elderly patients. Results showed that better or more positive religious coping was related to mechanisms such as religious forgiveness and seeking support, while poorer adjustments were associated with spiritual discontent and reprisal (18).

Whether seen as positive or negative, the efficacy of religious coping is determined by the interplay between personal, situational and societal factors. Therefore, the assumption that positive coping methods are necessarily adaptive and negative religious coping maladaptive, can lead to a narrow view of religious coping. While “positive” religious coping may be appropriate in one context, it may be problematic in another. For example, Phleps et al. found that patients who employed “positive religious coping” in their decision making process were more likely to pursue aggressive, costly and more invasive life prolonging care at end of life (29-31).

Role of the palliative care provider in spiritual care

Inherent in its philosophy as a medial subspecialty, palliative care has at its heart the maintenance and improvement of quality of life for patients and their families. As palliative care clinicians, we are uniquely positioned to work with teams/patients/families to explore the many variables that individuals and their families use as the guiding principles when making difficult decisions around end of life. While we are often consulted to manage physical symptoms, that is only part of our work. As we work on building relationships, both with our patients and their care team, we are often able to help facilitate communication that allows for greater understanding and fulfillment of the goals of care as expressed by those we care for.

Spiritual care has been recognized as one of the entities intimately connected to palliative care. The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care has published guidelines to shape clinical practice in palliative care. They provide a roadmap to direct the practice and provision of palliative care both in settings with established palliative care programs as well as in any setting where patient care is provided.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care have identified eight domains that are integral to palliative care as a discipline. Spiritual, religious and existential aspects of care are the fifth of these eight domains. The guidelines suggest that the interdisciplinary palliative care team include persons with education and training in pastoral care, and who are skilled in the assessment of and response to common spiritual issues faced by those who are facing life threatening illness. Additionally, these guidelines recommend the regular assessment, reassessment and documentation of spiritual concerns, as well as interventions to address issues that have been identified. They encourage the use of standardized tools where possible to assess and identify religious or spiritual/existential background, preferences and beliefs of the patient and family. We are also tasked with being advocates for patients’ religious and spiritual rituals that bring comfort, especially at the end of life (32).

As palliative care providers we are trained to connect with our patients in intimate ways, employing active listening, therapeutic silence and supportive dialogue to help our patient process and work through their issues. We are called to be fully present; we are called to put aside our agendas and to give ear and attention to the fears, distress, hopes, wishes as expressed by our patients. We are called to know the patient, to explore who they are, what things are important to them, what affects how they make decisions, and what gives their lives meaning. As a participant in a bereavement group so eloquently stated, we are called to “bear witness to their suffering.”

Spiritual assessment tools

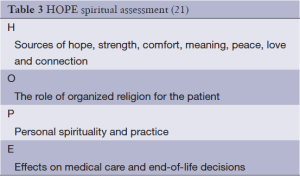

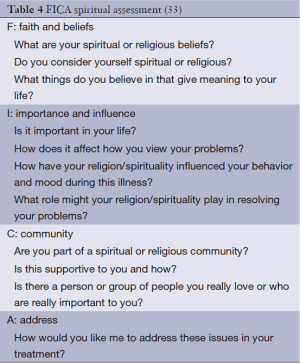

There are many validated tools that can be used to assess the spiritual history; one such tool is the HOPE spiritual assessment (Table 3) which can be used to assess the spiritual needs of the ill. Additionally there is the FICA (Table 4), which was created by Dr. Christina Puchalski in collaboration with primary care providers as a guide for clinicians to incorporate open-ended questions regarding spirituality into comprehensive histories. This tool asks about faith or beliefs, importance or influence, community and address (how can we include your spiritual values/preference in your care) (33). But often times, exploration of spiritual beliefs is a less formal process that can occur as part of any patient encounter. Clinicians may ask how patients have coped with challenging times in the past, and whether spirituality or religious beliefs were part of what helped them to cope. Spiritual assessment does not have to be a complicated process but may be as simple as asking “Is spirituality or religion something that is important to you?”

There are distinct advantages to formalized spiritual assessment tools including the detailed SPIRIT assessment (Table 5). They can serve as a framework within which to open conversations about spiritual matters. They also cross disciplines and can be used by any member of the health care team to gain information and insight into a patient’s spiritual concerns. However, use of such tools, if not done with sensitivity, can stand in the way of forming a therapeutic relationship. Patients may experience standardized assessments as insensitive to their current needs.

Barriers to spiritual care

Despite the clearly identified need for spiritual assessment and attention to spiritual needs as part of whole patient care, there are certainly barriers that exist. Many clinicians find it challenging to initiate discussions with patients about their spirituality. Some may feel discomfort because they do not see it as within their role or scope; others may think that patients will find such discussions too intimate or intrusive; yet others may not have personal spiritual or religious beliefs or practices, possibly leading to discomfort addressing such needs in their patients. Still others may have concerns about their inability to handle the information their patients present. Additionally, there is often concern for adequate time to assess and address concerns, as well as issues of privacy during visits, or lack of continuity of care between caregiver and patient. Daaleman and colleagues performed an Exploratory Study of Spiritual Care at the End of Life and found that other barriers included social, religious or cultural discordance between caregivers and patients that created an atmosphere of mistrust (35).

Yet most studies suggest that patients wish to have their spiritual concerns addressed (23,25,26,36-38). One of the benefits inherent to being a palliative care clinician is the truly interdisciplinary nature of this specialty. Within many palliative care teams there is a collaborative community including physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains or other spiritual care providers who have a role to play in the care of the patient.

Conclusions

Palliative care, at its core, seeks to relieve suffering, promote quality of life and provide care and comfort for those experiencing serious illness. Over the years, numerous studies have established the importance of religion, spirituality and religious coping in the context of serious illness. The assessment of and attention to spiritual needs have been identified as important factors in promoting quality of life, yet these needs often go unrecognized or unaddressed. As palliative care clinicians, we are uniquely positioned to work with teams/patients/families to explore the many variables that individuals and their families use as the guiding principles when making difficult decisions about life threatening medical issues. Unaddressed spiritual issues may frustrate one’s attempts to treat other symptoms, and have an adverse effect on quality of life. As each dimension is addressed in turn, distressing symptoms may be alleviated.

We have access to rich resources through collaboration with members of our interdisciplinary care team, allowing us to address the needs of our patients through a whole person approach. At the heart of our work as palliative care providers is the call to cure sometimes, treat often, and comfort always.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Institute of Medicine. eds. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington (DC), US: National Academies Press, 2008.

- Satcher D, Pamies RJ. eds. Multicultural Medicine and Health Disparities. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies Inc, 2006.

- Spillman BC, Lubitz J. The effect of longevity on spending for acute and long-term care. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1409-15. [PubMed]

- Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of older medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1108-12. [PubMed]

- Kaufman SR. Intensive care, old age, and the problem of death in America. Gerontologist 1998;38:715-25. [PubMed]

- Starr P. eds. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books, 1982.

- Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, et al. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:825-32. [PubMed]

- Health, United States, 2010. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus10.pdf. (Accessed 3/24/14).

- Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry 1980;137:535-44. [PubMed]

- Frankel RM, Quill TE, McDaniel SH. eds. The Biopsychosocial Approach: Past, Present, Future. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2003.

- Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000;284:2476-82. [PubMed]

- Daaleman TP, VandeCreek L. Placing religion and spirituality in end-of-life care. JAMA 2000;284:2514-7. [PubMed]

- Puchalski CM, Dorff RE, Hendi IY. Spirituality, religion, and healing in palliative care. Clin Geriatr Med 2004;20:689-714. [PubMed]

- Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:555-60. [PubMed]

- Hills J, Paice JA, Cameron JR, et al. Spirituality and distress in palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med 2005;8:782-8. [PubMed]

- Koenig HG. A commentary: the role of religion and spirituality at the end of life. Gerontologist 2002;42:20-3. [PubMed]

- Burkhardt MA. Spirituality: an analysis of the concept. Holist Nurs Pract 1989;3:69-77. [PubMed]

- Religion. [Def. 1b, 2, 4]. In Merriam Webster Online, Retrieved May 15, 2013. Available online: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/citation

- Puchalski C, Romer AL. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J Palliat Med 2000;3:129-37. [PubMed]

- Americans’ Spiritual Searches Turn Inward. Available online: http://www.gallup.com/poll/7759/americans-spiritual-searches-turn-inward.aspx. Accessed 3/18/2014.

- Anandarajah G, Hight E. Spirituality and medical practice: using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician 2001;63:81-9. [PubMed]

- Norris K, Strohmaier G, Asp C, et al. Spiritual care at the end of life. Some clergy lack training in end-of-life care. Health Prog 2004;85:34-9. [PubMed]

- Puchalski CM. Spirituality and end-of-life care: a time for listening and caring. J Palliat Med 2002;5:289-94. [PubMed]

- Palliative and Hospice Care: Framework and Practices. Available online: http://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/n-r/Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Framework/Palliative_and_Hospice_Care__Framework_and_Practices.aspx. Accessed 3/24/14.

- Sulmasy DP. Spiritual issues in the care of dying patients: “..it’s okay between me and god JAMA 2006;296:1385-92. [PubMed]

- Institue of Medicine. eds. Approacing death: Improving care at the End-of-Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997.

- Mitchell BL, Mitchell LC. Review of the literature on cultural competence and end-of-life treatment decisions: the role of the hospitalist. J Natl Med Assoc 2009;101:920-6. [PubMed]

- Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4131-7. [PubMed]

- True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, et al. Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: the role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med 2005;30:174-9. [PubMed]

- Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA 2009;301:1140-7. [PubMed]

- Pargament KI, Feuille M, Burdzy D. The brief RCPOE: Current psychometric status and a short measure of religious coping. Religion 2011;2:51-76.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Available online: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/guideline.pdf. Accessed 6/3/14.

- Borneman T, Ferrell B, Puchalski CM. Evaluation of the FICA Tool for Spiritual Assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:163-73. [PubMed]

- Maugans TA. The SPIRITual history. Arch Fam Med 1996;5:11-6. [PubMed]

- Daaleman TP, Usher BM, Williams SW, et al. An exploratory study of spiritual care at the end of life. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:406-11. [PubMed]

- Lo B, Ruston D, Kates LW, et al. Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life: a practical guide for physicians. JAMA 2002;287:749-54. [PubMed]

- Ehman JW, Ott BB, Short TH, et al. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1803-6. [PubMed]

- Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol 2012;23 Suppl 3:49-55. [PubMed]