Medical oncologist perspectives on palliative care reveal physician-centered barriers to early integration

Introduction

Early palliative care referral for patients with advanced cancer is associated with better quality of life, improved mood, and longer survival as compared to standard oncologic care (1-4). In addition, oncologists report that early and routine integration of palliative care for their patients with advanced cancer is acceptable, (5) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) definitively endorses early palliative care for all patients with advanced cancer (6). Despite strong clinical evidence and endorsement, early engagement with palliative care specialists occurs in fewer than 40% of patients with incurable cancer (7,8). It has been demonstrated that one reason for the low utilization rate of early palliative care is a perception from patients and caregivers that palliative care equates to end of life care and a terminal prognosis, and therefore there is a resistance to early palliative care integration from patients (9). As such, some have called for a “rebranding” of palliative care to highlight the benefits outside of end-of-life care domains that patients can expect from these interactions (10). Nonetheless, efforts to increase early palliative care referral for patients with advanced cancer are needed.

The objective of this study was to uncover important barriers to palliative care and end of life care planning from the perspective of medical oncologists. We hypothesized that medical oncologists would identify system-level barriers to palliative care referral [e.g., shortage of palliative care medicine specialists (11,12)] and would endorse interventions that increase collaboration among palliative care specialists, other oncologists, and other members of the interprofessional team to improve end-of-life care for patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

Participants

A sample of U.S. medical oncologists (N=31) was recruited through purposive, snowball sampling (13). Oncologists were recruited to participate in the study and were asked to refer other medical oncologists to the study investigators for recruitment. Physician study group participants were informed in the recruitment process that their responses were to be recorded, that their identities masked from the research team, and the transcripts were intended for research purposes. The study was reviewed and approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00204433), and determined not to be human subjects research; hence informed consent was deemed unnecessary.

Focus groups

Four professionally-moderated focus groups were conducted during the ASCO annual meeting in Chicago, Illinois. Focus group moderators were non-physician qualitative researchers from the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine. Focus groups began with questions to elicit participants’ experiences with end-of-life care and palliative care in their own clinical practices. Next, moderators prompted participants to discuss the optimal timing of palliative care referral, barriers to palliative care referral, and the role of other clinical team members in end-of-life care. Portions pertaining in particular to radiation oncologist participation have been previously published (14).

Analysis

Each focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and identifying information was removed. We used NVIVO 10 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) to organize and facilitate the analysis. Transcripts were analyzed using qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach. Four investigators from diverse healthcare backgrounds (SMK, medical oncology; TJK, radiation oncology; JMK, critical care medicine; MM, public health) independently reviewed each transcript, assigning a descriptive code to relevant sections of text. After the initial review of all focus group transcripts, the four study investigators met to review and collate preliminary codes into a coding taxonomy. The investigators then reviewed all four transcripts using the coding taxonomy and each coded section of text was assigned a consensus code during regular meetings of at least three investigators. The coding taxonomy was iteratively revised throughout the coding process. Higher-level analysis to evaluate relationships between codes and develop central themes was conducted through regular meetings of at least three investigators.

Results

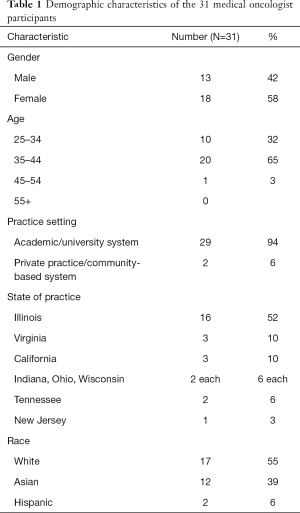

Demographic characteristics of the 31 participating medical oncologists are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants practiced in academic settings (29/31, 94%) and in Midwestern states (22/31, 71%). Our analysis identified common, typical practice patterns for ACP among medical oncologists’ and two major types of barriers to regular adoption of early palliative care referral for patients with advanced cancer: patient-centered barriers and medical oncologist-centered barriers.

Full table

Typical practice patterns for end of life care

First, medical oncologists described meeting the patient and outlining the general intent of treatment (curative versus palliative). Medical oncologists universally endorsed the importance of early communication and clarification about the intent of chemotherapy or other cancer-directed therapy (palliative versus curative treatment) with patients and their families. For example, one oncologist said, “With the first visit I always set the expectation that either this is palliative or curative and I explain what those things mean”.

Next, oncologists typically recommend therapy (and subsequent therapy) with integrated discussions of end of life care. Most oncologists described integrating discussions about prognosis and end-of-life planning “within the first few visits” for incurable patients, but maintained this practice pattern as separate from palliative care referral. A representative oncologist stated “We start usually by the second or third visit—I start talking about discussing with your family what you would want… I don’t want it to be a surprise once we’ve finished (fourth line) chemotherapy and I say I don’t have anything else. That’s when the transition would happen, but my goal is that they’re not surprised.”

The final step is to integrate palliative care and “transition” to hospice once available treatments have failed—“… but then the really intense discussion about what the end of life entails and really getting the palliative care team involved and all that happens when a patient really gets symptomatic.”

System and patient-centered barriers to palliative care referral

Medical oncologists rarely described system level barriers to palliative care referral, such as specialist shortage. However, one participant did note, “I don’t send all my patients to palliative care and I think you can only send, you know, however many the palliative care physicians can see.” Patient-centered barriers to early palliative care referral were reported more often, related to logistical burdens placed on patients with advanced cancer who are referred to a palliative care specialist. For example, one medical oncologist noted the burden of parking when coming to see a palliative care physician, in addition to all the other medical visits:

❖ “I know there’s this study out there about early palliative care, and I don’t tend to refer a ton of my patients for palliative care, despite the fact I like the group I feel like they’re already coming having to park, coming to a lot of visits, and to me it’s almost a barrier of do you want to see another provider.”

Additional patient-centered factors were identified, including perceived anxiety caused by these referrals: “I have many of my patients referred to palliative care, but for some of them, it’s actually mentally quite difficult to see the palliative care, even the way, you know, the appointments are structured and how much sicker the patients in those clinics are, I think, has reverberations for them.”

Medical oncologist-centered barriers to early palliative care integration

Medical oncologists acknowledged studies that demonstrated the benefits of early palliative care referral for patients with incurable cancer. Nonetheless, many medical oncologists described personal practice patterns that did not include early palliative care. Most medical oncologists described palliative care referral as a sequential event following the completion of all potential regimens of systemic or cancer-directed therapy, not an integrated parallel process ongoing for patients with advanced disease. To illustrate, a participant said, “My most successful maybe palliative care discussion has been when there is a conference between subspecialists, including palliative care, medical oncology, and intensivist, especially when the patient is in intensive care unit.” Another physician said, “Unless they become symptomatic I don’t include it (palliative care) in my practice.”

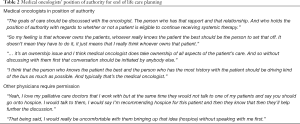

Medical oncologists’ position of authority

Medical oncologists voiced a unique position of authority related to palliative care referral and end-of-life planning for their patients (Table 2). Medical oncologists described themselves as “driving the bus,” “owning the patients,” and “holding the position of authority” when decisions about palliative care referral and end-of-life planning were under consideration. One participant explained:

❖ “I think we know it’s been published a ton in literature and we know one of the barriers to advance care planning and goals of care conversations with patients is often times a medical oncologist thinking they can do it better than anyone else, or that you have this sort of possessiveness of your patients. I think that’s for a reason, again, for all the reasons everyone said. We know them, we know their course the best, things like that.”

Full table

Other physicians such as palliative care specialists and radiation oncologists were thought to lack this authority to independently consider end of life planning, such as discussions about hospice care, by the majority of the participating medical oncologists. Instead, study participants preferred that palliative care and other physicians acted as reporters who could make the medical oncologist aware of changes in the patient’s condition and prognosis, but not make independent decisions about palliative care referral or end-of-life care with patients (Figure 1). An illustrative quote regarding radiation oncologists stated “I think the times where I think it’s worked well with radiation oncologists is when they talk to the patient, where they see them every day and see them declining and then communicate that with us.” Alternatively, other physicians could seek the permission of the medical oncologist to pursue end of life care discussions with patients (Table 2). For example, one participant said: “I think that the conversation needs to first be had with the oncologist. And if the oncologist says yes, absolutely you should have that conversation with my patient, then there shouldn’t be an issue. But if the oncologist says no, you’re crazy, that’s not what you should be talking about now, then that’s something different.”

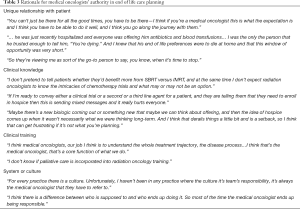

Rationale for position of authority

Medical oncologists expressed multiple reasons to support their unique position of authority in end of life care (Table 3). First, medical oncologists viewed the typical long-term relationship and rapport between themselves and patients as conferring a responsibility or duty to guide discussion and decisions about end of life care. To illustrate, a participant said: “I think if you’re a medical oncologist this is what the expectation is and I think you have to be able to do it well, and I think you go along the journey with them.” Other physicians such as surgeons and radiation oncologists were described as having transient involvement in the patient’s cancer care and lacking the same level of rapport or trust from patients to introduce palliative care services: “I love all the radiation oncologists I’ve worked with, but… there’s an end to their treatment. So I assume for them too it can be sort of awkward to have these conversations with a patient that they may never see again.”

Full table

Second, medical oncologists noted their unique clinical expertise and knowledge as a source of authority related to end of life care and the timing of palliative care and hospice referrals (Table 3). Medical oncologists described having knowledge about experimental treatments, clinical trials, or second and third line treatments and expressed concerns about other physicians discussing end of life care without knowledge of these cancer-directed therapies. “I agree with what everyone has said, the majority of the time it would be really difficult for the radiation oncologist to really initiate that, because they just may not be aware of what agents are available down the line for further medical treatments.” Similarly, medical oncologists expressed that palliative care physicians as inadequately trained in the clinical aspects of oncology: “So let me just say palliative care training has nothing to do with medical oncology.” Medical oncologists raised concerns that if they were not intimately involved in end-of-life conversations, prognosis, treatment options, and hospice may be discussed too early by other team members including radiation oncologists and palliative care physicians.

Third, medical oncologists described system-level or cultural features of clinical practices that reinforce the position of authority for medical oncologists in end of life care and decisions about palliative care referral (Table 3). Finally, medical oncologists questioned the capability and desire of physicians from other specialties, such as radiation oncology, to engage in end of life discussions and decisions about palliative and end-of-life care: “I’ve worked in a few different settings and I have not met many radiation oncologists willing to broach that subject.”

Consequences of medical oncologists’ authority

Medical oncologists discussed several consequences for physicians from other specialties who discuss end-of-life care without explicit permission (Table 4). For example, medical oncologists noted that they would stop referring to specific palliative care physicians that are viewed as encroaching on the medical oncologists’ role. Other consequences for physicians who were viewed as infringing on medical oncologists’ position of authority include interpersonal conflict. Said one medical oncologist “I think it’s a very common fear that general medicine docs have, hospitalists, everybody has is angering oncologists—I think that because oncologists tend to take such ownership of their patients so people don’t want to make decisions for the oncologists.”

Full table

Similarly, this position of authority led to the timing of palliative care referral and end-of-life care planning to be viewed as the domain of the medical oncologist alone; “I think there’s no role for radiation oncology in palliative care talk, at least for my patients.” An example quote regarding palliative care cited the concern that “They might not have the exact same vision of what’s going on. So I think I prefer to manage that.” The decision to continue chemotherapy or not was often framed as the “territory” of the medical oncologist, rather than a decision that a patient could make through consultation with varying providers (“So it’s the territorial idea of like you do your surgery yes or no and I’ll do my chemo yes or no”) while the integration of palliative care was described as a decision for the medical oncologist to make, not an option presented for patient-driven decision-making.

Divergent perspectives

Few medical oncologists who participated in this study emphasized the patient as the central figure in end of life care planning: “The patients will be the sort of captain of the ship (Figure 1).” Some medical oncologists described routine early utilization of palliative care: “I also introduce palliative care right out of the gate, so the idea is not waiting until we think they’re in their 11th hour and then try to bring in strangers.” Contrary to our hypothesis, an interprofessional, “all hands on deck” approach to early palliative care was rarely supported, but one medical oncologist stated “I think the more people who talk about advance care planning with patients and the more people who bring it up the better because then it’s something that becomes not as scary for people to talk about.”

Discussion

The care of patients with advanced cancer, especially near the end of life, is complex and is likely improved by an interprofessional team approach that serves to formulate optimal treatment plans that may include chemotherapy, radiation, and supportive oncology services such as palliative care and hospice. For patients with advanced disease, early palliative care is recognized as important yet challenging to implement due to multiple barriers. We hypothesized that medical oncologists would favor an interprofessional approach to palliative care integration and end-of-life care planning and would support early palliative care referral for patients with advanced cancer. Our results, however, did not support this hypothesis. Instead, we found that medical oncologists follow a practice pattern that reserves palliative care referral for late in a patient’s course of illness. In addition, we found that medical oncologists feel a strong sense of responsibility for and authority over decisions about palliative care referral and are skeptical of efforts by other clinical team members to initiate these referrals.

Previously identified physician barriers to earlier palliative care referral have included discomfort with end of life care (15), distress associated with the name “palliative” (9,16) as well as “clinician concern about taking away hope” and “unrealistic clinical expectations” about the efficacy of therapies (17). While physician barriers to high quality end-of-life care have been previously described, the most prevalent barrier (described by 97% of oncology survey respondents) was described as “unrealistic patient expectations” (17). However, our qualitative work finds that medical oncologists themselves often do not want to integrate palliative care services early. Uniquely, our results demonstrate that medical oncologists perceive themselves to have authority over the timing of palliative care referral and end of life care (their “territory”) thereby minimizing the potential input other providers can provide towards informed patient-centered decision making. Our findings are consistent with those of Gidwani and colleagues (18) who noted oncologists potentially viewing palliative care practitioners as a “team of outsiders”. Medical oncologists expressed concern that palliative care discussion of alternative options such as hospice enrollment could make the job of the medical oncologist more difficult, and result in inappropriately early termination of systemic therapy. However, a secondary analysis of the landmark Greer et al. trial demonstrated that the overall receipt of chemotherapy was not reduced by early integration of palliative care (19); similar findings have been demonstrated in patients undergoing phase I/II trials (20). These findings suggest an important misperception of medical oncologists that is a modifiable barrier to early palliative care referral.

This study highlights a critical opportunity for improved collaboration amongst oncologists (medical, surgical, radiation) and palliative care physicians, which may aid individual team members to feel autonomous in counseling patients regarding end-of-life care. Potential interventions to improve this collaboration could include a “tumor board” setting where multidisciplinary providers and supportive oncology (i.e., nutrition, social work, psychologist) could discuss complex patients care plans (21) ensuring providers are “on the same page” for patient prognosis and care plan. Addressing these barriers to early palliative care integration may significantly decrease health care expenditures, as has been suggested by studies examining the timing of palliative care (22). In addition, leveraging national initiatives, such as the CMS Oncology Care Model (23), may provide health systems and providers the necessary momentum to address some of the shortcomings identified in this study. The Oncology Care Model (OCM) is a demonstration payment model program by CMS that aims to improve the quality of cancer care while reducing cost. The OCM mandates a 13-element care plan that includes improvement in end-of-life care by providing patients with information on prognosis, treatment goals, and advanced care planning. The OCM’s emphasis on improving end-of-life care highlights the high cost of this portion of the cancer continuum. Participating practices are provided payments to improve elements of cancer care, and, based on our findings, we recommend a strong focus on increasing interprofessional collaboration to facilitate improved care for patients with advanced cancer.

Limitations of this study include our sample cohort, which mostly represented university-based practices and may therefore not be generalizable to other care settings. However, our study design did reveal important barriers to early palliative care integration, even though our sample would likely have better access to palliative care specialists compared to other care settings.

In conclusion, perceptions of medical oncologists towards palliative care, and their authority over this decision, appear to significantly limit early palliative care integration. Efforts to ensure cancer patients receive access to earlier palliative care services may be improved if end of life care is a patient-centered decision with input sought from the entire care team.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by an Institutional Research Grant from the American Cancer Society (IRG-15-173-21). JMK work was supported in part by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute under award numbers F32HL140824 and T32HL076139.

Footnote

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-270

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-270). TJK reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from OncLive, personal fees from Varian Medical Systems, and personal fees from Abbvie Inc., outside the submitted work. JMK reports grants from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, during the conduct of the study. JPG, MM, KK, ES, and SMK have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The project was reviewed by the Northwestern University IRB (STU00204433) and determined not to be human subjects research; hence informed consent was deemed unnecessary.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S, et al. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:394-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Le BH, Mileshkin L, Doan K, et al. Acceptability of early integration of palliative care in patients with incurable lung cancer. J Palliat Med 2014;17:553-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96-112. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1203-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:480-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ 2016;188:E217-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berry LL, Castellani R, Stuart B. The Branding of Palliative Care. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:48-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lupu D. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:899-911. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berendt J, Stiel S, Simon ST, et al. Integrating Palliative Care Into Comprehensive Cancer Centers: Consensus-Based Development of Best Practice Recommendations. Oncologist 2016;21:1241-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tracy SJ. Interview planning and design: Sampling, recruiting, and questioning. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2013.

- Gross JP, Kruser JM, Moran MR, et al. Radiation Oncologists' Role in End-Of-Life Care: A Perspective From Medical Oncologists. Pract Radiat Oncol 2019;9:362-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Cerana MA, Park M, et al. Impact of Oncologists' Attitudes Toward End-of-Life Care on Patients' Access to Palliative Care. Oncologist 2016;21:1149-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what's in a name?: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009;115:2013-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron NB, et al. Barriers to Quality End-of-Life Care for Patients With Blood Cancers. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3126-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gidwani R, Nevedal A, Patel M, et al. The Appropriate Provision of Primary versus Specialist Palliative Care to Cancer Patients: Oncologists' Perspectives. J Palliat Med 2017;20:395-403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:394-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyers FJ, Linder J, Beckett L, et al. Simultaneous care: a model approach to the perceived conflict between investigational therapy and palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;28:548-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang S, Doshi A, Smith CB, et al. Multidisciplinary tumor board for improvement of oncology collaboration in advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:175. [Crossref]

- May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. Prospective Cohort Study of Hospital Palliative Care Teams for Inpatients With Advanced Cancer: Earlier Consultation Is Associated With Larger Cost-Saving Effect. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2745-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kline RM, Bazell C, Smith E, et al. Centers for medicare and medicaid services: using an episode-based payment model to improve oncology care. J Oncol Pract 2015;11:114-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]