The end of life nursing education nursing consortium project

Introduction

With great strides made every day in medicine, many people believe that death is a distant reality. Yet, all of us will one day face the end of life and some, perhaps many, will suffer during this final journey. In the year 2000, the City of Hope and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) partnered to develop the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC), with the intent to educate health professionals on how to address the unique needs of the dying and the dying process itself. ELNEC’s goal was to educate undergraduate and graduate nursing faculty and students and practicing nurses on end of life care in train-the-trainer sessions. Once an ELNEC course was completed, the participants would return to their communities and train other nurses and healthcare providers, thereby extending the curriculum’s reach exponentially to the larger healthcare community. The aim of this paper is to share the international experiences of the ELNEC project and to raise awareness of the continued needs to advance palliative care internationally.

ELNEC was officially launched in February 2000, initially funded by a major grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). The National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Open Society Institutes (OSIs), Aetna, Archstone, Oncology Nursing, California HealthCare, and Cambia Health Foundations, Milbank Foundation for Rehabilitation, and the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) have provided additional funding since the program’s inception.

The ELNEC program is founded on the belief that the unique needs of the dying and the dying process itself can be addressed through hospice and palliative care. The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) describes palliative care as: “…a specialized medical care for people with serious illness. This type of care is focused on providing patients with relief from symptoms, pain, and stress of serious illness—whatever the diagnosis. The goal is to improve quality of life (QOL) for both the patient and family. Palliative care is provided by a team of doctors, nurses and other specialists who work with the patient’s other doctors to provide an extra level of support. Palliative care is appropriate at any age and at any stage of a serious illness and can be provided together with curative treatment” (1).

Palliative care nursing differs from other areas of nursing in that, “Palliative care nursing reflects a ‘whole person’ philosophy of care implemented across the life span and across diverse healthcare settings. The patient and family is the unit of care. The goal of palliative nursing is to promote QOL along the illness trajectory through the relief of suffering, and this includes care of the dying and bereavement follow-up for the family and significant others in the patient’s life” (2). To provide competent and effective palliative care, nurses and the healthcare community must be taught how to provide such care. ELNEC was designed to be a national education initiative for the nursing community to improve palliative care and make it readily available and accessible throughout the United States. In the fifteen years since ELNEC was first presented, the important role of palliative care in meeting the needs of the dying and the suffering patient has been recognized throughout the United States and the world. The history of the ELNEC program and its expansion internationally is detailed below.

The need for palliative care throughout the world

For over 30 years, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized the need and advocated for improved palliative care worldwide. As noted by N. Coyle, the WHO has modified its 1982 definition of palliative care to read as follows: “Palliative care is an approach to care which improves QOL of patients and their families facing life-threatening illness, through the prevention, assessment and treatment of pain and other physical, psychological and spiritual problems” (2).

According to the WHO, in 2011, there were a total of 54,591,414 deaths throughout the world (3). The population in developed countries has benefitted from advances in healthcare, in both detection and treatment; the result is that people are living longer. The increasing number of elderly that make-up the world’s population creates a host of new healthcare needs. In fact, in the United States, more than 70% of those who die each year are 65 years of age or older, many of whom suffer from long and debilitating illnesses. Cancer, cardiac disease, renal disease, and lung disease are among these debilitating illnesses. Close to 8 million deaths annually occur from cancer, with at least 84% of cancer patients believed to need palliative care (3). In 2012, 8.2 million people died from cancer, and 60% of the world’s newly diagnosed cancers are now occurring in developing countries (4). In modifying its palliative care definition, the WHO recognized the need to broaden the reach of palliative from exclusively end of life patients to include those patients receiving life-prolonging therapies as well (2). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) similarly recommended that palliative care be integrated with anti-cancer treatment. This suggests that cancer patients, when they are diagnosed and begin to contemplate life-prolonging therapies, should be introduced to palliative care as a tool to minimize the suffering and pain that can accompany their cancer care journeys. If provided from diagnosis on, palliative care can provide the cancer patient an extra level of support attuned to and tailored for not only their journey, but the journeys of their family and caregivers as well.

In 2011, an estimated 2.5 million people acquired human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and 1.7 million people died from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (5).

In 2013, there were approximately 35 million people living with HIV. Since the start of the epidemic, around 78 million people have become infected with HIV, and 39 million people have died of AIDS-related illnesses (6). In Kenya, 38% of all deaths will be due to HIV/AIDS (7). In 2011, it was estimated that this extremely high death rate has left more than 1,100,000 orphaned children (7). HIV/AIDS patients, in addition to medical treatment, require palliative care throughout their illness journeys to address the many symptoms that accompany the disease and to alleviate or at least lessen the suffering that it inflicts. Cancer, HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria are common life- threatening illnesses internationally, but many other diseases are also common and benefit from palliative care.

The unique role a nurse can play in palliative care

Unlike other healthcare professionals, nurses have the unique opportunity to spend time at the patient’s bedside, able to get to know the patient and family and their goals of care, explain different treatment options, and advocate for them (8). Because of the nurse’s positioning and unique role in patient care, nursing researchers at the City of Hope in California, in the late 1990’s, began to examine nursing curricula and the extent to which nursing students were being educated in end of life care. Their research revealed a need for new comprehensive curricula to enable nursing faculty to properly teach nursing students how to care for terminally ill patients and their families (9,10).

The origins of ELNEC

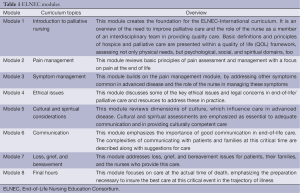

In 1997, the AACN created guidelines to add end of life care to undergraduate nursing education. In Peaceful Death: Recommended Competencies and Curricular Guidelines for End-of-Life Nursing Care (AACN, 1997), the AACN outlined end of life competencies for undergraduate nursing students (11). Following this effort, AACN, together with the City of Hope, supported by a major grant from the RWJF, developed the ELNEC-Core curriculum, arising from the Peaceful Death document. In eight modules, the ELNEC-Core curriculum was designed to provide nursing education for undergraduate nursing faculty, continuing education providers, and staff development educators (Table 1). The modules included: an introduction to palliative nursing; pain management; symptom management; ethical issues; cultural and spiritual considerations; communication; loss, grief, and bereavement; and final hours.

Full table

The ELNEC-Core course was based on a train-the-trainer concept: the participants/trainees would participate in the multi-day training program, then take the 1,000+ page supporting materials and the lessons learned during the course back to their hospitals, healthcare staffs, and community and impart the training to those with whom they worked. In January, 2001, in Pasadena, California, ELNEC held its first train-the-trainer course and since then, over 19,500 nurses, physicians, social workers, chaplains, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals have attended one of 160 national/international ELNEC courses. Trainers from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and 85 countries world-wide have participated in ELNEC training courses. These nursing educators, in turn, returned to their nursing schools and healthcare systems and introduced the ELNEC content into nursing curricula, annual competencies, and new employee orientations. The ELNEC curriculum has been translated into the Spanish, Russian, German, Korean, Japanese, Chinese, Romanian, Armenian, and Chinese languages.

Thanks to the dedication and commitment of the trainers who present these courses, the ELNEC network is carrying through on its commitment to improve the care of the seriously ill and dying by educating caregivers and changing systems of care. To-date, over 500,000 healthcare providers have attended a regional ELNEC course (12).

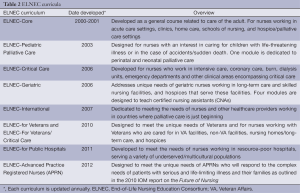

ELNEC has developed nine programs (Table 2) including ELNEC-Core; ELNEC-Pediatric Palliative Care; ELNEC-Critical Care; ELNEC-Geriatric; ELNEC-International; ELNEC-for Veterans, ELNEC-for Veterans/Critical Care, ELNEC-Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN), ELNEC-for Public Hospitals, and Integrating Palliative Oncology Care into Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) and Clinical Practice—as recently as 2013 to educate DNP and clinicians in palliative care (12).

Full table

In 2014 alone, it is estimated that 7,600 people were trained in the ELNEC curriculum. ELNEC trainers traveled to and presented 254 regional and international courses in 39 states, the District of Columbia, and ten international countries, including Austria, Canada, Ethiopia, Germany, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Turkey and Vietnam. During 2015, ELNEC has scheduled 11 train-the-trainer courses to be held across the US, with an additional four to be presented internationally in Beijing, China; Kipkaren, Kenya, Salzburg, Austria, and Tirana, Albania. Great strides have been made in promoting palliative care worldwide. It is ELNEC’s goal to educate and enable the healthcare community to provide excellent, compassionate palliative care worldwide, across all geographical, political, financial, religious, and ethnic boundaries.

The need to educate internationally: developing an international curriculum

The availability of palliative care internationally is mostly limited to Western Europe, North America, and Australia/New Zealand. In parts of Africa, Asia and the Middle East, no known palliative care is available. In fact, 32% of all countries fall into this category. Low and middle income countries greatly need palliative care, but it is in these countries where it is least available (3). In 2005, the national ELNEC Project Team began to focus on creating an international curriculum. They convened a group of nurses and physicians experienced in international palliative care and using the ELNEC-Core curriculum as their starting point, considered over the course of the year how to adapt the curriculum for international participants.

Central tenets in the ELNEC-Core curriculum that were also applicable to an international curriculum include: the family as the unit of care; the key role and positioning of the nurse as a patient advocate; the importance of honoring the patient’s/family’s culture; focusing attention on the special populations, including children and the elderly, the socially/economically disadvantaged, homeless, or mentally ill; taking into consideration the patient’s psychosocial and spiritual needs, in addition to his/her physical needs; providing palliative care across all settings, including clinics, acute care, homecare; the influence of socioeconomic and political issues; and the importance of interdisciplinary care (13).

The ELNEC team included The Standards of Practice for Culturally Competent Nursing Care in each of the ELNEC-International modules (14). Examples of these standards are promoting social justice (standard 1) for all citizens; encouraging nurses to take into account their personal values, beliefs, and cultural history to better inform how they receive and care for their patients (standard 2); participating in healthcare policymaking to address deficiencies in palliative care and insure that palliative care meets a standard of excellence (standard 6). By its very nature, ELNEC-International had to take into account that cultures vary country to country and that these variances are significant in the death and the dying process. In fact, culture is such a key issue, that one of the eight curriculum modules focuses entirely on cultural considerations (standard 8); the other seven modules include cultural concepts as well.

Pain relief

In creating a curriculum for international participants, the ELNEC International team had to consider that medications available in the United States might be in limited supply or not available at all in the countries they would visit and address. Specifically, opioids that are vital for pain relief may not be available in developing countries. The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) reported that in the period 2010-2012, 92% of the world’s morphine was consumed by just 17% of the world’s population, primarily in the countries in North America, Western Europe and Oceania (15).

The remaining 83% of the world’s population consumed just 8% of the worldwide morphine supply (15). The INCB reports that this limited distribution of narcotics for pain relief is particularly troubling since 70% of the deaths from cancer occur in low and middle income countries (15). Further, the INCB projects that “without sustained action” the occurrence of cancer will increase 70% in middle-income countries and 82% in lower-income countries by 2030 (15). In a 2010 published report, INCB stated that countries were hindered by their own regulatory and procurement policies as well as concerns about addiction, reluctance to prescribe, stock, and adequately train their healthcare professionals (15).

Mwangi-Powell, Downing, Powell, Kiyange, and Ddungu, in “Palliative Care in Africa”, in the Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care, 4th edition, describe the particularly unfavorable drug environment in Africa stating that “…despite the overwhelming medical need, access to even the simplest pain-relieving medication—not to mention the strong painkillers (i.e., opioids)—and antibiotics to treat opportunistic infections in many African countries is provided within very restrictive and operational environments” (16).

As a result of the INCB statistics which indicate that in many of the world’s healthcare professionals have to care for end of life patients without being able to provide adequate pain relief, the ELNEC curriculum had to be adapted for the international community at large. Specifically, the ELNEC committee had to adapt the Pain, Symptom management and Final hours’ modules to make them applicable to countries that did not have access to pain relief medication. The reality was that providing a 2-hour lecture on opioid use for intractable pain was of no use to nurses and other healthcare professionals from countries without access to pain-relieving medications.

Cultural considerations in healthcare decision-making

Other overarching factors had to be taken into account when adapting the ELNEC-Core curriculum to an international audience. For example, in the United States, as a general practice, patients are informed about their medical conditions, so that they can make their own healthcare decisions. However, informing patients of their medical conditions and empowering them to make their own healthcare decisions is not the general rule throughout all countries of the world. In some cultures, family members make health decisions for their ill family member and they may prefer not to inform the ill family member of the extent of his or her life-threatening illness. They may fear the family member will lose hope and the will to live, contemplate or commit suicide, and suffer needlessly as a result. Although this belief system may be in direct contrast to that of the instructing nurse, the nurse must respect the cultural framework, beliefs, and values of the host country where he or she is teaching.

Cultural competence

Cultural competence is another ELNEC theme, especially applicable in an international setting. An instructor who travels to teach in another country needs to be aware of, attuned to, and compassionate with the host country’s beliefs and practices with regard to healthcare. This may include end of life healthcare practices regarding nutrition and hydration, pain and symptom management, life prolonging measures, and death and mourning rituals. Nurses must be aware of how their own personal beliefs and cultural practices affect how they perceive other’s cultural practices. In “Cultural Considerations in Palliative Care”, in the Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care, 4th edition, Manzanec and Panke explain cultural competence: “According to Campinha-Bacote’s model for enhancing cultural competence, there are five components essential in pursuing cultural competence: cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, cultural encounter, and cultural desire” (17). Manznec and Panke further state: “Cultural awareness challenges the nurse to look beyond his or her ethnocentric view of the world, asking the question ‘How are my values, beliefs, and practices different from those of the patient and family’ rather than ‘How is this patient and family different from me?’”(17). This self-examination and self-reflection is especially important when the nurse educator travels to other parts of the world to teach end of life care.

Cultural considerations: suffering, ethics and family caregiver needs

The Cultural considerations, Communication, Ethics, and Loss/grief/bereavement modules used in ELNEC-Core also had to be adapted for use in the international community. Throughout the countries of the world, suffering is not always addressed and family caregiver needs not always recognized. How ethical issues arise in the different countries and how they are handled may differ as well. The CORE modules referenced above needed to be made applicable to the wider international audience; their inclusion in the international curriculum serving as a reminder to nurses to assess these aspects in the patients for whom they care.

Understanding the role of the nurse in different countries

In order to properly prepare for teaching internationally, ELNEC faculty needed to converse with members of the host country well in advance of the course (18,19). In addition to the cultural considerations that affect the country’s healthcare practices and the availability of pain relief drugs discussed above, the nurse educators need to understand the basic framework within which the nurse participants work. Quite simply, what role does the nurse play in the country’s healthcare system and more specifically in end of life care and whether the nurse functions as part of a healthcare team or in an individual capacity. In Africa, specifically in rural areas, the nurse may well be the only healthcare professional available. As a result, some countries are creating legislation to enable palliative care-trained nurses to prescribe medications such as morphine (16). It is essential that the ELNEC educators understand not only the cultural context, but the reality of the nurse’s role in the system, before teaching internationally, so they are able to teach in a manner that will be well received. Understanding the culture is more than just grasping the ethnicity, race, and religion of the town, community, or nation (17).

Launching ELNEC international

In 2006, 38 nursing leaders in education and clinical practice, from 14 Eastern and Central European, former Soviet, and Central Asian countries attended the first ELNEC-International program in Salzburg, Austria. The OSI and the Open Medicine Institute (OMI), through the Salzburg Seminars program, collaborated in producing the program. The program was a success, with Eastern European nurses, who were leaders in clinical practice and education, participating. Four additional courses were held in Salzburg in 2008, 2011, 2012, and 2014, and a fifth ELNEC course in Salzburg is scheduled for September, 2015.

International training continues

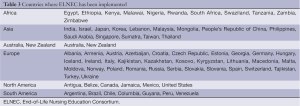

Other ELNEC International courses have been successful (Table 3) (13,18-20). In Nairobi, Kenya, in 2009, two Kenyan national and local physician leaders invited five ELNEC faculties (four advanced practice nurses and one physician) to Nairobi to present a one-week ELNEC-International course. Forty-nine healthcare professionals, including clinical nurses, social workers, and chaplains in addition to faculty attended the 5-day train-the-trainer course.

Full table

In 2014, ELNEC International courses were taught in ten countries, including Austria, Canada, Ethiopia, German, Japan, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Turkey, and Vietnam. It is estimated that over 5,800 nurses and other healthcare providers have received ELNEC training internationally. Of note, the first ELNEC course taught in Chinese was the ELNEC-Pediatric Palliative Care course presented to 450 nurses in Taiwan in June 2014.

In May, 2015, a team of ELNEC trainers from the US (three advanced practice nurses and one physician) will travel to Kipkaren, Kenya, a remote village with a recently built 26-bed hospice called Kimbilio. Here, the team will provide education to the staff of the hospice, as well as make home visits, provide assistance in the out-patient clinic located on the grounds of the hospice, and present grand rounds at the hospice. Due to the tremendous success of Kimbilio, ELNEC trainers from Swaziland and Ethiopia will join the American team to witness the work being accomplished at the hospice in Kipkaren, and learn how to accomplish similar work in their countries. The ELNEC team will share their successful efforts in Romania, Mexico, Korea, Japan, Tanzania, and many other countries.

Throughout the ELNEC project, we have attempted to conduct evaluation to demonstrate the outcomes of the education. Numerous papers have been published by the ELNEC team and others documenting the impact of ELNEC training (21-30).

Future directions

The ELNEC team is dedicated to continuing this work throughout the world. There is great interest in well-developed health care systems as well as developing countries and many countries that began with our Core curriculum are now interested in also using our Pediatric, Geriatric and Critical Care curricula. We launched ELNEC in China in April 2015 with a fully translated version and look forward to the great opportunities for expansion in China. Through regional leadership we also hope to reach many countries that have not initiated palliative care and to support those leaders around the world who are making remarkable progress.

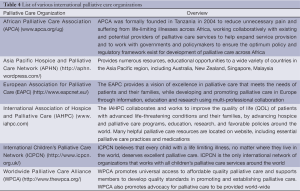

There is still much work to be done to advance palliative care throughout the world and international palliative care organizations are dedicated to this mission (Table 4). The ELNEC team is dedicated to continuing this work and to foster regional leaders around the world who can support other countries in their areas. Nurses are uniquely positioned to play a key role in bringing palliative care to resource-poor countries and the world at large. The nurses who participate in ELNEC International devote their time, effort, and skill to educating health professionals in caring for end of life patients. These nurses work to promote ELNEC principles worldwide so that the physical, psychological, spiritual, and social needs of all terminally ill patients are addressed, and their suffering is lessened from disease diagnosis to end of life. By doing so, these nurses increase palliative care awareness, so that one day end of life care is recognized as a public health and human right issue and that patients the world over can “achieve a ‘decent’ or ‘good death’—‘one that is free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers; in general accord with patients’ and families’ wishes; and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural and ethical standards” (2).

Full table

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Center to Advance Palliative Care. Available online: https://www.capc.org, accessed April 25, 2015.

- Coyle N. Introduction to palliative nursing. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice JA. eds. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015:4-8.

- Connor SR. International initiatives. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice JA. eds. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015:1056.

- International Childhood Cancer Day. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/en/, accessed February 2, 2015.

- Kirton CA, Sherman DW. Patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice JA. eds. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015:628.

- World AIDS Day 2014 Report - Fact sheet. Available online: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/campaigns/World-AIDS-Day-Report-2014/factsheet, accessed February 20, 2015.

- Boit J, Ototo R, Ali Z, et al. Rural Hospice in Kenya Provides Compassionate Palliative Care to Hundreds Each Year. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 2014;16:240-5. Available online: http://journals.lww.com/jhpn/Abstract/2014/06000/Rural_Hospice_in_Kenya_Provides_Compassionate.10.aspx

- Dahlin CM, Wittenberg E. Communication in palliative care: an essential competency for nurses. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice JA. eds. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Ferrell BR, Virani R, Grant M, et al. Evaluation of the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium undergraduate faculty training program. J Palliat Med 2005;8:107-14. [PubMed]

- Malloy P, Paice J, Virani R, et al. End-of-life nursing education consortium: 5 years of educating graduate nursing faculty in excellent palliative care. J Prof Nurs 2008;24:352-7. [PubMed]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). Peaceful Death: Recommended Competencies and Curricular Guidelines for End-of-Life Nursing Care, 1997. Available online: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec/publications/peaceful-death, accessed April 25, 2015.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). ELNEC Fact Sheet,2015. Available online: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec/about/fact-sheet, accessed on April 25, 2015.

- Ferrell B, Virani R, Paice JA, et al. Evaluation of palliative care nursing education seminars. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2010;14:74-9. [PubMed]

- Douglas MK, Pierce JU, Rosenkoetter M, et al. Standards of practice for culturally competent nursing care: 2011 update. J Transcult Nurs 2011;22:317-33. [PubMed]

- International Narcotics Control Board. Availaibility of narcotic drugs for medical use. Available online: https://www.incb.org/incb/en/narcotic-drugs/Availability/availability.html, accessed February 5, 2015.

- Mwangi-Powell FN, Downing J, Powell RA, et al. Palliative care in Africa. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice JA. eds. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015:1127.

- Manzanec P, Panke JT. Cultural Considerations in Palliative Care. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice JA. eds. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015:588.

- Malloy P, Paice JA, Ferrell BR, et al. Advancing palliative care in Kenya. Cancer Nurs 2011;34:E10-3. [PubMed]

- Paice JA, Ferrell BR, Coyle N, et al. Global efforts to improve palliative care: the International End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Training Programme. J Adv Nurs 2008;61:173-80. [PubMed]

- Kim HS, Kim BH, Yu SJ, et al. The Effect of an End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Course on Nurses’ Knowledge of Hospice and Palliative Care in Korea. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 2011;13:222-9.

- Barrere C, Durkin A. Finding the right words: the experience of new nurses after ELNEC education integration into a BSN curriculum. Medsurg Nurs 2014;23:35-43, 53. [PubMed]

- Head BA, Schapmire T, Faul AC. Evaluation of the English version of the End-of-Life Nursing Education Questionnaire. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1375-81. [PubMed]

- Grant M, Wiencek C, Virani R, et al. End-of-life care education in acute and critical care: the California ELNEC project. AACN Adv Crit Care 2013;24:121-9. [PubMed]

- Shea J, Grossman S, Wallace M, et al. Assessment of advanced practice palliative care nursing competencies in nurse practitioner students: implications for the integration of ELNEC curricular modules. J Nurs Educ 2010;49:183-9. [PubMed]

- Ferrell BR, Virani R, Malloy P. Evaluation of the end-of-life nursing education consortium project in the USA. Int J Palliat Nurs 2006;12:269-76. [PubMed]

- Ferrell B, Virani R, Malloy P, et al. The preparation of oncology nurses in palliative care. Semin Oncol Nurs 2010;26:259-65. [PubMed]

- Gabriel MS, Malloy P, Wilson LR, et al. End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC)–For Veterans: An Educational Project to Improve Care for All Veterans With Serious, Complex Illness. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 2015;17:40-7.

- Malloy P, Paice J, Coyle N, et al. Promoting palliative care worldwide through international nursing education. J Transcult Nurs 2014;25:410-7. [PubMed]

- Paice JA, Erickson-Hurt C, Ferrell B, et al. Providing pain and palliative care education internationally. J Support Oncol 2011;9:129-33. [PubMed]

- Paice JA, Ferrell B, Coyle N, et al. Living and dying in East Africa: implementing the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium curriculum in Tanzania. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2010;14:161-6. [PubMed]