Optimal participation in decision-making in advanced chronic disease: perspectives of patients, relatives and physicians

Introduction

Making decisions about health care in the complex situation of advanced serious illness is a difficult process where clinical evidence is often limited (1). Psychosocial factors and the preferences of patients and their families appear to play an important role in achieving beneficial and reasonable outcomes. Therefore, the patients’ and relatives’ involvement in those decisions is desirable as a key feature of a patient-centered care (2). Although the patients’ participation in decision-making is generally acknowledged by health care providers (3,4), its realization is hindered by significant barriers. For example, ICU physicians may focus more on physiological and technical parameters rather than on patient’s preferences (5). Relatives, on the other hand, may argue that involvement in decision-making would be too stressful for the patient (6) and that differences in opinion regarding the actual decision-making are a strong factor contributing to intra-family conflicts (7).

In the complex situations of a serious illness, it is often not possible to make a fully informed decision because the course of the illness of the individual patient is difficult to predict and the decisions must be made provisionally to achieve intermediate goals (1). For that reason, a linear concept of shared decision-making, proposed by Charles et al. (8) as a four-step process—(I) the involvement of the patient and the physician; (II) information sharing between the two parties; (III) the expression of treatment preferences on each side; (IV) a consensus over a treatment plan—might not be efficient enough for the patients to make good decisions. For Epstein et al. (1), the process is a more dynamic and iterative one and must involve a support in constructing the patient’s preferences by reflecting on the communication process itself, specifying how much information a patient wants to get and how relatives should be involved in the decision-making.

There are different ways to measure patient preferences for decisional control (9) used in quantitative studies, such as CPS (The Control Preferences Scale by Degner) (10) or API-D (autonomy preference index-D) (11), where the results of the decisional control preferences are usually presented as either active (decision made by the patient), shared (decision made by the patient and the physician together) or passive (decision made by the physician).

In the systematic review on patients’ preferences for their participation in the decision-making in palliative care setting, Bélanger et al. (12) found that between 68% and 87% of patients prefer either a shared or an active role in the decision-making. Similar results were found for older adults—33% for a shared and 49% for an active role (13). In a recent international multicenter study of 1,490 patients with advanced cancer, the preferences for shared, active and passive decisional control were 33%, 44% and 23%, respectively (14). Evidence also shows that, in most cases, physicians may not be able to predict the patients’ preference for decision-making (15). Studies on shared decision-making often focus on the dyadic interaction between the patient and the physician, while the role of family members or relatives and the preferences for their involvement in the decision-making remain much less explored and so do the measure instruments (16). Laidsaar-Powell et al. (17), in their systematic review, summarized, inter alia, the attitudes of the patients, the relatives and the physicians toward the triadic shared decision-making structure. The results suggest that approximately one third of patients believe that all three parties should have an equal role in the decision-making, one third would prefer the physician to have the major role and one third of patients would prefer to make decisions by themselves. Regarding the role of the relatives, more than half of physicians and relatives believed that relatives should play a more important role in the decision-making process than they actually do. Results of a recent mixed-method study on the triadic decision-making showed important disagreements among physicians, patients and relatives about the relatives’ decision-making preferences and their influence on the final decision (16). In a retrospective view on the decision-making process, patients and relatives felt that physicians had more influence than the physicians themselves felt to be the case. The disagreement between patients and caregivers about the decision-making preferences was another common phenomenon emerged from this study. In general, the triadic process of decision-making and the views of patients, physicians and relatives on the roles of each other in that process are very little understood, and research data are scarce. This study brings an original analysis of three different perspectives on engagement of patients, physicians and relatives in decision-making in the situation of an advanced disease. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2368).

The aim of this study is to explore the perspectives of patients with advanced chronic disease, of their relatives and of their physicians on the role each of them play in the process of health care decision-making.

Methods

This study was a part of the IMPAC project (Integrative model of prognostic awareness in advanced cancer)—a multi-method study of prognostic awareness in advanced cancer patients.

Study population

Participants were recruited from oncology and non-oncology departments of four hospitals in the Czech Republic (two University hospitals, two regional hospitals).

Inclusion criteria for patients were a diagnosis of advanced incurable disease, life expectancy less than one year as estimated by their physicians using the “surprise question” method (18), and the cognitive ability to participate in the survey. The study also included relatives of eligible patients and physicians working in data collection sites—treating physicians of eligible patients and their colleagues.

Study design

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was conducted with approval from the Ethics Committees of all hospitals included in the study and by Ethics Committee of research institution Center for palliative care, Prague, Czech Republic, ref. 27/5/2015.

Eligible patients were contacted during hospitalization by their physicians, eligible relatives were contacted during their visits in hospital: those who agreed to participate were then introduced to a trained researcher, who informed them about the purpose of the study, and informed consent was taken from all the respondents. The survey was administered as a face-to-face structured interview for patients and a self-administrated questionnaire for relatives and physicians.

The part of the questionnaire analyzed in this paper was focused on how respondents perceive the role of patients, relatives and physicians in the health care decision-making process. Participants were asked to rank how important, from their own point of view, should the role of the patient, the physician and the relative be on a scale from 0 to 10, with the possibility to rank all actors with the same score (Figure 1). The study also collected basic demographic data—age, sex, education and spirituality for all groups, and diagnosis and prognostic awareness for the patient group. Prognostic awareness was defined as understanding the illness’ curability and was measured by the question “Do you consider your disease as curable or incurable?”, where the answer “incurable” was considered as the accurate prognostic awareness.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of responses for the option “patient”, “physician” and “relative” was examined, the differences between respondent groups (patient/relative/physician) were observed by analysis of variance, the significance of these differences (P=0.05) was examined by the Levene test in IBM SPSS 21.

For the next analysis, a typology of answers was constructed for each participant. First, the option “patient” was considered as a central category (patient autonomy is perceived as the level of the patient’s participation in the decision-making process in relation to the physicians’ and the relatives’ role) and three categories of combinations of answers were constructed: the patient’s voice is more important than that of the others (active role), the patient’s voice is equal to that of the others (shared decision-making) and the patient’s voice is less important than that of the others (passive role). Second, for the analysis of the triadic relation of the decision-making process, a typology of nine possible combinations was constructed. The distribution and relations among these variables were examined, the significance of the results was observed by the chi-square test (P=0.05) and adjusted residuals.

Results

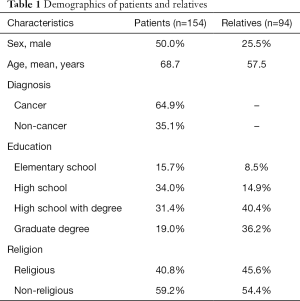

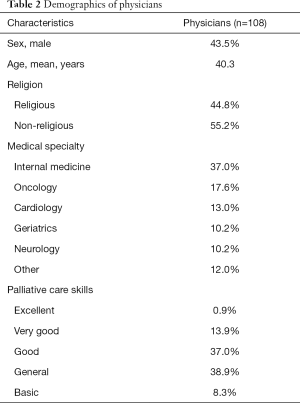

Sample size was adequate to provide necessary statistical power in each of three groups (patients =170, relatives =113, physicians =108), response rate was 91%; 16 patients and 19 relatives refused to participate. Non-responders were mostly women (n=30). The most common reason for refusing interview was lack of interest (mainly in group of relatives) or physical and psychological barriers (in group of patients). We enrolled 154 patients, 108 physicians and 94 relatives. The participants’ demographics are summarized in Tables 1,2. The mean age of the patients and relatives was 68.7 and 57.5, respectively; 64.9% of patients had cancer. Forty-eight percent of the patients believed that their disease was curable. The most common kinship status of the relatives was daughter (40.0%), spouse (22.0%) and son (13.0%). The physicians’ specializations were most often internal medicine (37.0%), oncology (17.6%) and cardiology (13.0%). The physicians rated their palliative care skills as: excellent (0.9%), very good (13.9%), good (37.0%), general (38.9%) and basic (8.3%).

Full table

Full table

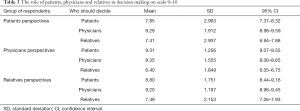

When asked to rank the importance of each of the three roles in the decision-making process on a scale from 0 to 10, the patients attributed the most important role to the physicians [mean 9.29; 95% confidence interval (CI): 8.98–9.59], then to themselves (mean 7.85; 95% CI: 7.37–8.32) and then to their relatives (mean 7.41; 95% CI: 6.94–7.88). The relatives rated the importance in the decision-making in the same sequence—physicians mean 9.20 (95% CI: 8.96–9.45), patients’ mean 8.80 (95% CI: 8.44–9.16) and relatives’ mean 7.49 (95% CI: 7.06–7.93). On the other hand, from the physicians’ point of view, the most important role should be played by patients (mean 9.31; 95% CI: 9.07–9.55), followed by physicians themselves (mean 8.35; 95% CI: 8.06–8.65) and finally by relatives (mean 6.40; 95% CI: 6.05–6.75) (Table 3).

Full table

Although all participants put the scores higher than 7 to all three “actors” (patients, physicians, and relatives), we found statistically significant differences between the respondent groups. The physicians indicated that the role of the patients in the decision-making should be stronger (mean 9.31; 95% CI: 9.07–9.55) than the patients themselves ranked it (mean 7.85; 95% CI: 7.37–8.32). On the other hand, when asked about the role of physicians, both the patients and the relatives rated the role of the physicians in the decision-making significantly higher (mean 9.29; 95% CI: 8.98–9.59 and mean 9.20; 95% CI: 8.96–9.45 respectively) than did the physicians themselves (mean 8.35; 95% CI: 8.06–8.65). The role of the relatives was considered to be stronger by the patients and the relatives themselves (mean 7.41; 95% CI: 6.94–7.88 and mean 7.49; 95% CI: 7.06–7.93 respectively) than by the physicians (mean 6.40; 95% CI: 6.05–6.75).

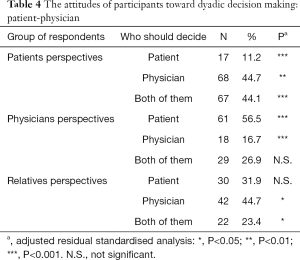

In the analysis of the dyadic interactions, we used the three categories of the patients’ decisional control preferences (active, shared and passive) and here we found correlations between the respondent groups and their preferences. When we compared the preferred involvement of patients vs. physicians in the dyadic decision-making, patients preferred to be active in 11.2%; to have a shared input into the decisions with their physician in 44.1%; and to be passive and let the physician have the strongest word in 44.7%. As for physicians, the majority (56.5%) thought that patients should play the most important role in the decision-making and 26.9% preferred the decision-making to be shared. As for relatives, most of them believed that in the dyadic patient-physician decision-making, patients should be active (31.9%) or should have a shared role (23.4%) in the decision-making with their physician, and 44.7% of relatives believed that the physician should have the strongest word. The strongest positive correlations were found between being a patient and a preference for shared decisions, and between being a physician and a preference for active decisions of the patients (Table 4). The strongest negative correlations were found between being a physician and passive decisional preferences of patients, and between being a patient and an active decisional preference of patients (Table 4).

Full table

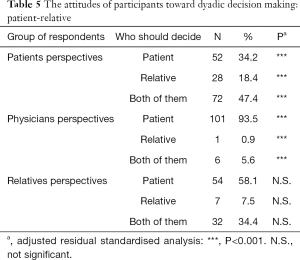

When we compared the preferred involvement of the dyad of patients - relatives, 47.4% of patients thought that they should have equal word in the decision-making as their relatives, 34.2% of patients would prefer to be more active than their relatives and 18.4% of patients would prefer their relatives to be more active in the decision-making than they themselves. A large majority of physicians (93.5%) believed that patients should be more active than relatives, 5.6% of physicians were for shared decision between patients and relatives and only 0.9% of physicians would ascribe a more active role to relatives than to patients.

Most relatives (58.1%) would also prefer an active role of the patients but more than one third (34.4%) found the shared decision-making between patients and relatives the most acceptable option, and only 7.5% of relatives would like to be more active in the decision-making than the patients. The strongest positive correlations were found between being a patient and preferences for active decisions of patients and shared decisions of patients and relatives, and between being a physician and preferences for active decisions of patients (Table 5). The strongest negative correlations were found between being a patient and a stronger role of the relatives than the patients, and between being a physician and a stronger or shared role of relatives (Table 5).

Full table

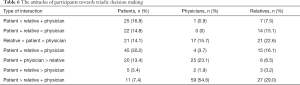

Analyzing the attitudes of the participants towards the triadic decision-making, there are nine possible combinations of interactions (Table 6). The most significant preference of the patients was either an equal role of the three actors (30.2%) or a more active role of the physician and the relative than the role of the patient (16.8%). For physicians, the most preferable type of interaction was an active role of the patient compared to the physician and the relative (54.6%). The least preferable types of interaction were those with the most active role of the physician compared to the patient and the relative (either physician + relative > patient or physician > patient + relative). The relatives also highlighted the active role of the patient compared to the physician and the relative (29.0%), but it was less statistically significant.

Full table

In the analysis of the sociodemographic and illness-related factors, we have found a significant association between age and the active role of the patients, with younger participants preferring a more active role of patients. This is due to lower mean age in the group of physicians. Analyzing each group of the respondents separately, we have not found any association between the role in the decision-making and age, education, spirituality, diagnosis and the patients’ prognostic awareness. Also, we have not found any significant association between physicians’ views on decision-making and their specialty and between relatives’ views on decision-making and their kinship status towards the patients.

Discussion

Our results show a difference in attitudes toward decision-making between patients, physicians and relatives. Physicians and relatives tend to accentuate the active role of patients either in dyadic or triadic interactions, while patients mostly prefer shared decision-making both in dyadic interaction with physicians and triadic interaction patient-physician-relative. Physicians also seem to underestimate the importance of the role of relatives in the decision-making in general while patients and relatives would prefer a more active participation of the relatives in the decision-making.

Comparing our results of patients’ views with the study by Nolan et al. (19), the most important difference can be found in the dyadic patient-physician decisional preferences, where, in Nolan’s study, 15% of patients preferred a passive role compared to 44.7% in our study, and 34% of patients preferred an active role compared to 11.2% in our study. Regarding the patient-relative dyad, in Nolan’s study, 50% of the patients preferred an active role in decision with their relatives, compared to 34.2% in our study; 44% of patients preferred a shared decision compared to 47.4% in our study; and 6% preferred a passive role compared to 18.4% in our study. Similar to our results, Nolan found no significant association between sociodemographic variables and the decision-making preferences.

In Yennurajalingam’s international study of 11 countries (14) there is also a stronger inclination towards an active role of patients in the patient-physician dyad (25% vs. 11.2% in our results), but almost similar in the patient-relative dyad (37% vs. 34.2%). In the triadic interaction, Yennurajalingam’s study results also show that patients would opt for a more active (44%) attitude towards the decision-making than in our results (24.2%), but Yennurajalingam’s comparison is made between the group of patients on the one hand and the group of physicians and relatives put together on the other, whereas in our study, the three groups are analysed separately, giving nine possible combinations of interactions. Also, the two above mentioned studies focused only on the views of the patients on the decision-making process, while our study compares the views of the patients, the physicians and the relatives.

In the study of LeBlanc et al. (16), the patients, physicians and relatives were asked to look at the triadic decision-making process retrospectively. Partial results of this study show that 46% of patients and 41% of relatives felt that the decision had been entirely influenced by physicians, while among physicians, only 17% thought they had such an active role. Interestingly, we have found similar numbers when asking about attitudes. 44.7% of patients and 44.7% of relatives thought physicians should play the most active role in the decision-making while only 16.7% of physicians thought that way. That may imply how attitude can have impact on this process and its evaluation.

Patients in all studies mentioned in the discussion as well as patients in our study were either patients with palliative care needs or patients with limited prognosis. Even though our results do not show any association between patients’ view of decision-making process and their prognostic awareness, the generalization of these results to other group of patients would require further research with specific patient population (e.g., different diagnosis) or a larger sample.

Although many physicians believe that they are already providing enough space for the patients to participate in the decision-making, in reality, shared decision-making demand more profound changes of attitudes of all parties involved in the process (20). The understanding of autonomy as a capacity to make an independent rational choice based on the information provided by the physician, and not paying enough attention to the interdependence and the social context of the patients’ decisional preferences, mainly in the situation of advanced illness (21), are some of the main barriers of those changes. The person-centered approach, a well-defined concept integrated in other disciplines such as psychiatry and geriatrics, but taken as rather implicit and not much studied in palliative care (22), takes into account the patient as a person with her whole life experience and within her social relations. One of the main goals of this approach is to help patients to make meaningful decisions based on person’s individual narrative and life’s experience (23) through the process of shared decision-making. To support shared decision-making does not mean merely to provide information or knowledge and to restrain the physician’s effort to push through his own view on what is in the patient’s best interest (24). It also requires to reflect on the power disbalance in the patient-physician relationship; to redefine the patient’s role; and to help the patients to engage in the process on the basis of their own values and life experiences; and to involve their significant others if the patient desires. Recent studies imply that special communication trainings (20) and trainings focused on goals of care conversations (25) and shared decision-making consultations (26) are important to change physicians’ attitudes towards more person-centered care.

The results presented in this study lead to the interpretation that physicians do want to provide more space in the decision-making but they often do not know how, and that patients do want their relatives to be more engaged as a support, because the patients do not know what to expect from an expert-lead consultation and therefore do need more support.

This study has several limitations. First, the main method used in this study was an original questionnaire, not previously tested for its psychometric properties. The method was only piloted for face validity and feasibility in a small group of patients, clinicians and relatives (<10 in each group). The second limitation is the small sample of the study, which limits especially the interpretation of the triadic interactions—here nine combinations were found and the count in some of the combinations was very low. Though statistically the results presented here are significant, their clinical significance may be questionable due to the small sample size. A qualitative study could bring further insight into the differences in the perceived roles among patients and their caregivers. The small sample size also does not enable detailed analysis of the association between the role in decision-making and the type of diagnosis, type of kinship status of relatives, type of specialty of physicians etc. A third limitation is the fact that physicians recruited for the study were not only the physicians taking care of the recruited patients, but also other physicians taking care of seriously ill patients in general. For that reason, we talk about the attitudes of three groups of respondents more than about the actual triads. And finally, participants were asked to think about the roles in a decision-making process concerning health care issues in general. Although all patients were in an advanced state of an incurable disease, the question of health care issues may have different meaning for each of them.

Conclusions

Physicians should assess patients’ preferences for the decision-making process and for their relatives’ involvement. This study confirms that attitudes towards participation in the decision-making in the situation of advanced stage of incurable disease differ significantly between patients, physicians and relatives, and that physicians expect more active involvement from patients than do relatives and patients themselves. This study also shows that physicians underestimate the role of the relatives as expected by the patients and the relatives themselves. More research is needed to elucidate into greater depth the process of decision-making within the triad of actors—patient, physician and relative—and the factors that influence patients’ and relatives’ preferences for decisional control.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grant No. 17-26722Y, Czech Science Foundation.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2368

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2368

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2368). The authors reports grants from Czech Science Foundation, during the conduct of the study.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was conducted with approval from the Ethics Committees of all hospitals included in the study and by Ethics Committee of research institution Center for palliative care, Prague, Czech Republic and informed consent was taken from all the respondents.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Epstein RM, Gramling RE. What Is Shared in Shared Decision Making? Complex Decisions When the Evidence Is Unclear. Med Care Res Rev 2013;70:94S-112S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frank RK. Shared decision making and its role in end of life care. Br J Nurs 2009;18:612-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:892-9. [PubMed]

- Pollard S, Bansback N, Bryan S. Physician attitudes toward shared decision making: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:1046-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Visser M, Deliens L, Houttekier D. Physician-related barriers to communication and patient- and family-centred decision-making towards the end of life in intensive care: a systematic review. Crit Care 2014;18:604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Su C, Sharma R, Williams B, et al. Family Matters: Effects of Birth Order, Culture, and Family Dynamics on Surrogate Decision Making (FR407-B). J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:418. [Crossref]

- Wilson DM, Anafi F, Roh SJ, et al. A Scoping Research Literature Review to Identify Contemporary Evidence on the Incidence, Causes, and Impacts of End-of-life Intra-Family Conflict A Scoping Research Literature Review to Identify Contemporary Evidence on the Incidence, Causes, and Impa. Health Commun 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Charles C, Whelan T, Gafni A. What do we mean by partnership in making decisions about treatment? BMJ 1999;319:780-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Auerbach SM. Do Patients Want Control over their Own Health Care? A Review of Measures, Findings, and Research Issues. J Health Psychol 2001;6:191-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: What role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:941-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, et al. Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy. J Gen Intern Med 1989;4:23-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bélanger E, Rodríguez C, Groleau D. Shared decision-making in palliative care: A systematic mixed studies review using narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2011;25:242-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiu C, Feuz MA, McMahan RD, et al. “Doctor, Make My Decisions”: Decision Control Preferences, Advance Care Planning, and Satisfaction With Communication Among Diverse Older Adults. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:33-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yennurajalingam S, Rodrigues LF, Shamieh OM, et al. Decisional control preferences among patients with advanced cancer: An international multicenter cross-sectional survey. Palliat Med 2018;32:870-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruera E, Sweeney C, Calder K, et al. Patient preferences versus phsysician perceptions of treatment decisions in cancer care. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2883-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc TW, Bloom N, Wolf SP, et al. Triadic treatment decision-making in advanced cancer: a pilot study of the roles and perceptions of patients, caregivers, and oncologists. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1197-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laidsaar-Powell RC, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. Physician–patient–companion communication and decision-making: A systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient Educ Couns 2013;91:3-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, et al. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:abstr 9588.

- Nolan MT, Hughes M, Narendra DP, et al. When patients lack capacity: the roles that patients with terminal diagnoses would choose for their physicians and loved ones in making medical decisions. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30:342-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ 2017;357:j1744. Erratum in: BMJ 2017;357:j2005. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Houska A, Loučka M. Patients' Autonomy at the End of Life: A Critical Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:835-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Öhlén J, Reimer‐Kirkham S, Astle B, et al. Person‐centred care dialectics—Inquired in the context of palliative care. Nurs Philos 2017;18:e12177 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Håkansson Eklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, et al. "Same same or different?" A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:3-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 2014;94:291-309. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schellinger SE, Anderson EW, Frazer MS, et al. Patient Self-Defined Goals: Essentials of Person-Centered Care for Serious Illness. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018;35:159-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation