A cross-sectional study of the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of obstetricians, gynecologists, and dentists regarding oral health care during pregnancy

Introduction

Oral health is an important part of general health and affects the whole body. In 2010, the World Health Organization listed it among the ten most important standards of human health (1). However, some physiological changes during pregnancy, such as pregnancy gingivitis, benign oral masses (like pregnancy epulis), gomphiasis, dental erosion, tooth decay, pericoronitis, and periodontitis, may have a negative impact on oral health (2,3). Oral infection during pregnancy not only increases the incidence of preeclampsia, premature delivery, and low infant birth weight (4,5) but also causes the vertical transmission of cariogenic bacteria between mother and fetus (6), resulting in the occurrence of early dental tooth decay in the child. However, many pregnant women do not realize the significance of oral health to themselves and their fetuses and rarely seek the diagnosis and treatment of oral diseases during pregnancy. Previous studies in China have found that only a third of pregnant women have regular oral examinations (7,8). In other developed countries, the proportion of pregnant women using dental services is also low: in the United States only 23–49% of pregnant women seek oral health care, while, in the United Kingdom and Australia, this figure is 33–64% and 30.5–33%, respectively (9-12). There are many factors that influence whether a pregnant woman seeks oral health care, including difficulty accessing medical treatment, a lack of awareness of oral health care, lack of understanding of dental treatment during pregnancy, and fear that dental treatment will endanger fetal health. It is therefore important that pregnant women understand the changes to their gums and teeth that occur during pregnancy, strengthen their oral hygiene habits, and treat existing oral problems quickly in order to maintain good oral health during pregnancy and avoid prolonging any oral diseases.

The results of the present study show that the three main sources of oral health knowledge for pregnant women are mass media, advice from medical staff, and the experiences of their friends and relatives. This is slightly at odds with the main ways in which they expect to obtain knowledge: the guidance of medical staff, lectures, and mass dissemination. The results also show that pregnant women most frequently visit an obstetrics and gynecology department where, due to a lack of knowledge regarding oral hygiene during pregnancy, medical staff rarely recommend dental examinations and treatment. Furthermore, dentists often refuse to provide oral treatment services to pregnant women for a variety of reasons.

Previous studies have demonstrated that, while most health care professionals agree on the importance of oral health and acknowledge the need for oral health care during pregnancy, only a few dentists perform general dental care for pregnant women. Furthermore, while obstetricians were found to be more comfortable with their patients undergoing dental procedures during pregnancy but seldom advised pregnant women to visit a dentist (13-15). To date, no study has been conducted in China to evaluate health care providers’ perceptions of oral health care during pregnancy.

The present study issued a questionnaire to obstetricians, gynecologists, and dentists in general hospitals, maternal and child health hospitals, stomatological hospitals, and dental clinics in Beijing in order to understand the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of health care providers regarding the oral health care of pregnant women. The aim of the study was to provide a basis for strengthening the continued education of health care providers, thereby helping them to offer better health care to pregnant women. We present the following article in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1520).

Methods

Research subjects

This study was conducted as a cross-sectional clinical investigation. Between February and June 2019, 300 obstetricians and gynecologists and 300 dentists at Beijing medical institutions (general hospitals, maternal and child health hospitals, stomatological hospitals, and dental clinics) were selected as subjects for cross-sectional investigation using the convenient sampling method.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by ethics board of Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital (No.:19196-0-01) and informed consent was taken from all individual participants.

Research methods

Researchers who had been trained in a uniform way conducted an anonymous questionnaire by mail and on-site distribution. The survey tool was based on the national consensus statement for oral health care during pregnancy introduced by the National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center (OHRC) and on the Pregnant Women Survey questionnaire published (16), which was adjusted to take into account the situation of medical institutions in China and the main purpose of the study (Appendix 1).

Research data

The main data of the study consisted of participants’ basic data and data on oral health and pregnancy, oral health consultations for pregnant women, and oral treatment and drug use among pregnant women. In the questionnaire, the five-point Likert scale (strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree/disagree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree) was adopted for questions regarding oral health and pregnancy and oral health consultations for pregnant women. Questions regarding the frequency of oral care provided by doctors to pregnant women used a scale of “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” and “never.” Knowledge-based questions were scored based on correct and incorrect answers: a correct answer was given one point, while an incorrect answer was given zero. A total of 20 knowledge-based questions were asked (maximum score 20), and participants were placed into two groups based on their score: group I (<10) failed, while group II (≥10) passed.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the awareness rate of respondents regarding questions on oral health and pregnancy and the dental treatment and safety of drug use for pregnant women. A percentage was used to describe respondents’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, and a χ2 test was used to compare differences. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to further explore potential influencing factors related to knowledge of oral health during pregnancy.

All statistical analyses were carried out using a two-sided test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General data

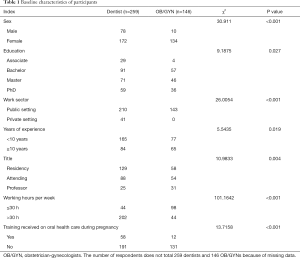

A total of 600 questionnaires were sent out, of which 405 were returned (response rate 67.5%). Women, staff with a bachelor’s degree or higher, staff in public hospitals, and staff with less than 10 years’ work experience made up the largest proportion of respondents. The percentage of subjects who had undergone professional training in oral health for pregnant women was relatively low. There were significant differences between dentists and obstetricians and gynecologists in gender, place of practice, number of years of work, number of working hours per week, and opinions on whether training in oral health care for pregnant women should be conducted (all P<0.05, Table 1).

Full table

Obstetricians’, gynecologists’, and dentists’ knowledge of oral health care during pregnancy

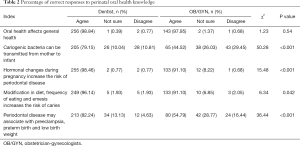

To investigate obstetricians’, gynecologists’, and dentists’ knowledge of oral health care during pregnancy and the safety of oral treatment for pregnant women, the study proposed five categories of associated knowledge: (I) oral health affects general health; (II) changes in hormone levels during pregnancy increase the risk of periodontal disease in pregnant women; (III) changes in dietary structure and lifestyle habits during pregnancy increase the risk of cavities in pregnant women; (IV) cariogenic bacteria can be transmitted vertically between the mother and fetus; (V) periodontal disease during pregnancy is associated with preeclampsia, premature birth, and low infant birth weight. For (I), (II), and (III), obstetricians, gynecologists, and dentists all demonstrated a good understanding, with the range of correct answers being 91.1–98.84%. For (IV) and (V), however, the cognitive accuracy of all respondents decreased: the range of correct answers for dentists was 79.15–82.24%, while that of obstetricians and gynecologists was only 44.52–54.79%. The difference was statistically significant (P<0.05, Table 2).

Full table

Obstetricians’, gynecologists’, and dentists’ awareness of the safety of oral treatment during pregnancy

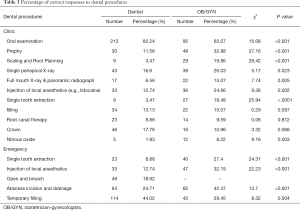

The overall knowledge level of obstetricians, gynecologists, and dentists regarding the safety of dental treatment for pregnant women was low: the rate of correct answers was lower than 50% in all cases except for the question regarding oral examinations, where dentists achieved a score of 82.24% and obstetricians and gynecologists achieved a score of 65.07%. Obstetricians, gynecologists, and dentists also placed different emphasis on oral indicators. Regarding basic oral treatments or operations, such as supragingival scaling, subgingival scaling, root surface leveling, single-tooth extraction, and nitrous oxide sedation, the cognitive accuracy of obstetricians and gynecologists was significantly higher than that of dentists. However, for dental film radiography and other complex oral procedures, including crown repair, abscess incision and drainage, and pulp filling, the cognitive accuracy of dentists was significantly higher than that of obstetricians and gynecologists (P<0.05, Table 3).

Full table

Obstetricians’, gynecologists’, and dentists’ attitudes and barriers to offering oral health services during pregnancy

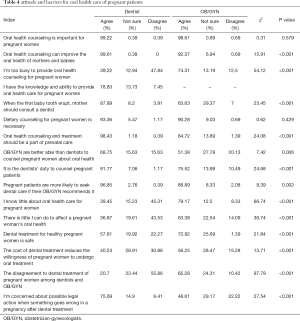

It was found that almost all dentists (99.22%), obstetricians, and gynecologists (98.61%) believed it important to carry out oral health care consultations, including diet consultations, for pregnant women. Furthermore, 99.61% of dentists and 92.37% of obstetricians and gynecologists believed that oral health care consultation during pregnancy could improve maternal and infant oral health. A total of 96.85% of dentists and 88.89% of obstetricians and gynecologists agreed that advice from obstetricians and gynecologists would improve the willingness of pregnant women to see a doctor for oral health care, and 78.83% of dentists believed they had the ability to provide oral health care to pregnant women. However, only 57.81% of dentists believed it was safe for pregnant women to undergo oral treatment, compared to 72.92% of obstetricians and gynecologists.

Exploration and analysis of the potential barriers to providing oral health care during pregnancy showed that dentists believed the main factors were fear that oral treatment complications in pregnant women would lead to medical disputes (75.69%), that obstetricians were more likely to consult on oral health care for pregnant women (68.75%), and that the cost of treatment would reduce the willingness of pregnant women to seek it (40.23%). Obstetricians and gynecologists, however, believed that the main factors were a lack of knowledge of oral health care (79.17%), that it was the role of dentists to provide oral health care consultations for pregnant women (75.52%), and that the outpatient department was too busy to offer oral health care to pregnant women (74.31%, Table 4).

Full table

Obstetricians’, gynecologists’, and dentists’ provision of oral health care to pregnant women

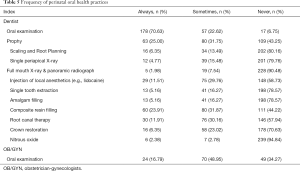

While 70.63% of dentists stated that they had provided oral examinations to pregnant women, only 16.79% of obstetricians and gynecologists stated that they had. It was stated that dental cleaning was often provided during pregnancy, and about a quarter of dentists said that they had used resin filling for pregnant women. Around 10% of all respondents stated that they had carried out local anesthesia and root canal therapy on pregnant women, while more than 90% had never used nitrous oxide sedation during pregnancy (Table 5).

Full table

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of obstetricians’, gynecologists’, and dentists’ knowledge of oral health during pregnancy

The questionnaire included 20 questions related to oral health during pregnancy. Each correct answer was given one point, with a maximum possible score of 20. The respondents were divided into two categories based on their score: group I (<10) failed, while group II (≥10) passed. Using group II (≥10) as the dependent variable, binary logistic regression analysis was used to further explore the factors affecting obstetricians, gynecologists’, and dentists’ knowledge of oral health care for pregnant women.

The results of the univariate analysis showed that the professional title of doctor was negatively correlated with the knowledge of oral health care for pregnant and post-partum women (OR =0.517, 95% CI: 0.315–0.848). After further adjusting for factors like gender, education level, number of hours worked, number of years of work experience, and whether or not they had received professional training, the correlation was still statistically significant (OR =0.444, 95% CI: 0.236–0.836). However, in univariate and multivariate analysis, there was no statistical correlation between the respondents’ level of knowledge and their gender, education level, number of hours worked, number of years of work experience, and whether or not they had received professional training.

Discussion

The results showed that 98.61% of obstetricians and gynecologists and 99.22% of dentists recognized the importance of oral health care during pregnancy. However, 79.17% of obstetricians and gynecologists thought they lacked knowledge of oral health care for pregnant women. All respondents believed that the cost of treatment was one of the main barriers to offering oral treatment to pregnant women, although dentists also believed that medical disputes were a significant barrier. A small number of obstetricians and gynecologists provided oral health care during pregnancy. The results of logistic regression analysis showed that the professional title of doctor was negatively correlated with knowledge of oral health care for pregnant women.

Oral health problems in pregnant women have recently attracted the attention of scholars both in China and abroad. New York, California, OHRC, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have released oral health care guidelines during pregnancy and a national census (17,18). The Chinese census data projections in 2010 stated that there would be around 346 million women of childbearing age in China by 2018 and that around 16 million women of childbearing age would be pregnant each year. The theme of 2016’s Dental Day in China was “Oral Health, General Health,” which advocated paying attention to oral health care throughout life. Its first slogan was “Mom stays away from dental disease and gives birth to a healthy baby.” The National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China issued the Oral Health Action Programme [2019–2025] and emphasized that oral health services should cover the whole population and the whole life cycle. Oral health knowledge is also a key part of the pre-marital physical examination, maternal health management, and the pregnant women’s school curriculum. Obstetricians, gynecologists, and dentists therefore all play a key role in preventing oral disease and encouraging the oral hygiene education of pregnant women.

The present study is the first in China to examine dentists’, obstetricians’, and gynecologists’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding oral health care for pregnant women. The results of the study found that the knowledge level of dentists with respect to oral health was significantly higher than that of obstetricians and gynecologists. Only around half of obstetricians and gynecologists correctly answered the questions on knowledge categories (IV) and (V) (“cariogenic bacteria can be transmitted vertically from mother to child” and “periodontal disease during pregnancy is related to preeclampsia, premature birth, and low infant birth weight”). Almost all obstetricians and gynecologists (98.61%) and dentists (99.22%) agreed on the importance of oral health care during pregnancy. The results of this study are similar to those of studies from the United States and Australia (13-15,19,20).

In the present study, 79.17% of obstetricians and gynecologists stated that they felt they lacked knowledge of oral health care for pregnant women, which was the most significant barrier to them providing oral health care services to pregnant women. For dentists, medical disputes were their primary concern. All respondents agreed that the cost of treatment was one of the main barriers to offering oral treatment to pregnant women. Similarly, an American study found that insurance payments and the cost of oral health care were common reasons for patients avoiding visiting a doctor of stomatology; the same study also found that doctors were unwilling to provide oral health treatment to pregnant women (13).

In the present study, respondents’ knowledge level regarding the safety of oral treatment for pregnant women was very low. Dentists gave more conservative estimates of the level of safety, while obstetricians and gynecologists were less concerned about medical risks, possibly because obstetricians and gynecologists understand the overall condition of pregnant women and assess the risk of disease more accurately. Obstetricians and gynecologists also provided more counseling and referrals. Therefore, oral treatment, which has a high clinical risk, was greatly reduced.

Regarding the provision of oral treatment to pregnant women, most of the dentists interviewed in the present study were limited in the extent to which they provided oral examinations to pregnant women (70.63%). Very few obstetricians and gynecologists provided oral treatment, such as cleaning, local anesthesia, and root canal therapy, to pregnant women. The proportion of comprehensive oral health care for pregnant women in this survey was much lower than that of previous surveys: a study conducted in North Carolina, U.S., showed that 48.3% of the subjects were provided with more comprehensive dental services (15).

In order to understand the factors affecting dentists’, obstetricians’, and gynecologists’ knowledge of oral health care for pregnant and post-partum women in this study, logistic regression analysis was carried out. This identified a negative correlation between the professional title of doctor and knowledge of oral health care for pregnant and post-partum women (OR =0.517, 95% CI: 0.315–0.848). This correlation highlights the importance of continued education on oral health care for pregnant women.

Conclusions

The study showed that there is still a lack of knowledge of oral health care for pregnant women in China, which influences the attitudes and behaviors of dentists, obstetricians, and gynecologists. One of the reasons for this lack of knowledge could be that there are few relevant treatment norms in the sector and that medical staff consider the medical risks of oral treatment more carefully, with most doctors adopting a “stay away” approach towards the treatment of oral diseases in pregnant women. As such, it is suggested that basic and continued education on oral health care for pregnant women should be strengthened for dentists, obstetricians, and gynecologists, which would reduce the occurrence of oral diseases and establish oral health management during pregnancy. Another recommendation is to increase social security support and medical insurance for pregnant women’s oral treatment in order to reduce medical and patient costs. Relevant authorities may also be able to increase awareness of oral health care during pregnancy and improve treatment practices by issuing unified treatment guidelines as soon as possible.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1520

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1520

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1520). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by ethics board of Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital (No.:19196-0-01) and informed consent was taken from all individual participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Petersen PE. World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health—World Health Assembly 2007. Int Dent J 2008;58:115-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobylińska A, Sochacki-Wójcicka N, Dacyna N, et al. The role of the gynaecologist in the promotion and maintenance of oral health during pregnancy. Ginekol Pol 2018;89:120-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liwei Z, Jing Z, Yong Y, et al. Management of oral diseases during pregnancy. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2017;35:113-8. [PubMed]

- Boggess KA. Maternal oral health in pregnancy. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:976-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Odermatt T, Schötzau A, Hoesli I. Oral Health and Pregnancy - Patient Survey using a Questionnaire. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol 2017;221:180-6. [PubMed]

- Basha S, Shivalinga Swamy H, Noor Mohamed R. Maternal Periodontitis as a Possible Risk Factor for Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight--A Prospective Study. Oral Health Prev Dent 2015;13:537-44. [PubMed]

- Kashetty M, Kumbhar S, Patil S, et al. Oral hygiene status, gingival status, periodontal status, and treatment needs among pregnant and nonpregnant women: A comparative study. J Indian Soc Periodontol 2018;22:164. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chawla RM, Shetiya SH, Agarwal DR. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Pregnant Women regarding Oral Health Status and Treatment Needs following Oral Health Education in Pune District of Maharashtra A Longitudinal Hospital-based Study. J Contemp Dent Pract 2017;18:371-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dasanayake AP, Gennaro S, Hendricks-Muñoz KD, et al. Maternal periodontal disease, pregnancy, and neonatal outcomes. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2008;33:45-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas NJ, Middleton PF, Crowther CA. Oral and dental health care practices in pregnant women in Australia: A postnatal survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008;8:13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- George A, Ajwani S, Bhole S, et al. Promoting perinatal oral health in South-Western Sydney: A collaorative approach. J Dent Res 2010;89:142301

- Hullah E, Turok Y, Nauta M, et al. Self-reported oral hygiene habits, dental attendance and attitude to dentistry during pregnancy in a sample of immigrant women in North London. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008;277:405-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strafford KE, Shellhaas C, Hade EM. Provider and patient perceptions about dental care during pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2008;21:63-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- George A, Dahlen HG, Reath J, et al. What do antenatal care providers understand and do about oral health care during pregnancy: a cross-sectional survey in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:382-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Da Costa EP, Lee JY, Rozier RG, et al. Dental care for pregnant women: an assessment of North Carolina general dentists. JADA 2010;141:986-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oral Heallth Care During Pregnancy Expert Workgroup. Oral Health Care During Pregnancy: A National Consensus Statement. Washington, DC: National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center, 2012.

- California Dental Association Foundation. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, District IX. Oral health during pregnancy and early childhood: evidence-based guidelines for health professionals. J Calif Dent Assoc 2010;38:391-440.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women's Health Care Physicians. Committee Opinion No. 569: oral health care during pregnancy and through the lifespan. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:417-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huebner CE, Milgrom P, Conrad D, et al. Providing dental care to pregnant patients: a survey of Oregon general dentists. JADA 2009;140:211-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curtis M, Silk HJ, Savageau JA. Prenatal Oral Health Education in U.S. Dental Schools and Obstetrics and Gynecology Residencies. J Dent Educ 2013;77:1461-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]